RIDING THE YOSHIMURA SUPERBIKE

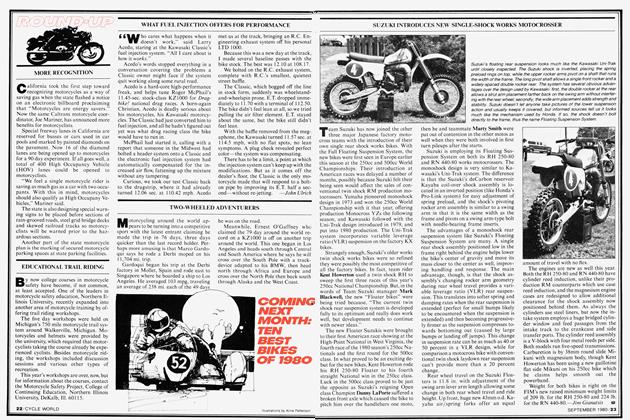

Watching, reading about or even discussing the Yoshimura R&D of America Suzuki GS1000 Superbike with its creators is one thing. Riding it is another.

I had already sampled the bike’s forerunner late in 1977, when I entered a club race at Ontario Motor Speedway to test the Yoshimura 944cc GS750 used by Steve McLaughlin to win Laguna Seca that year. The power was overwhelming; the stable, neutral handling amazing; the combination devastating. The bike hammered home the influence that machinery has on lap times. After two practice sessions and an Open GP third place behind the TZ750s of Steve McLaughlin and Roberto Pietri, I wheeled the GS750 back into the pits to find Pops, clipboard and stopwatches in hand, grinning ear-to-ear.

“John Ulrich go crazy,” said Pops. “You go 2:10 lap time. First, 2:12, then 2:11, finally 2:10.76. You go crazy.”

The Superbike Production lap record at the time was 2:08.9, held by class champion Reg Pridmore. My previous best lap had been a high 2:17.

The machine was magic.

I expected more of the same from Yoshimura’s 1978 Superbike, a Suzuki GS1000. In the bike’s Ontario debut, Cooley lowered the lap record to 2:06.25. In the AFM Six-Hour, the Yoshimura GS1000 blasted away from the 944cc GS750 I rode, leaving the smaller motorcycle behind on the straightaways. I could hardly wait to ride the GS1000.

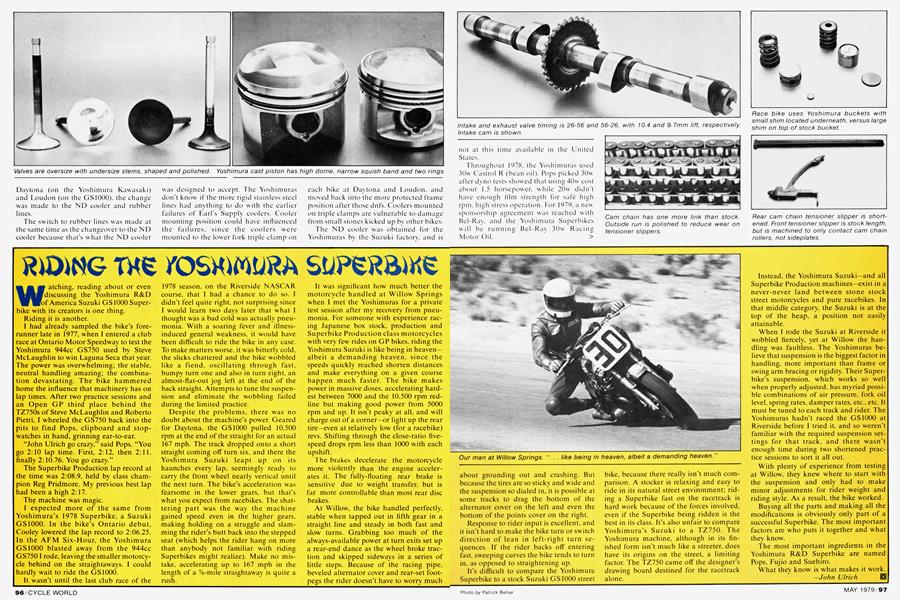

It wasn’t until the last club race of the 1978 season, on the Riverside NASCAR course, that I had a chance to do so. I didn’t feel quite right, not surprising since I would learn two days later that what I thought was a bad cold was actually pneumonia. With a soaring fever and illnessinduced general weakness, it would have been difficult to ride the bike in any case. To make matters worse, it was bitterly cold, the slicks chattered and the bike wobbled like a fiend, oscillating through fast, bumpy turn one and also in turn eight, an almost-flat-out jog left at the end of the back straight. Attempts to tune the suspension and eliminate the wobbling failed during the limited practice.

Despite the problems, there was no doubt about the machine’s power. Geared for Daytona, the GS1000 pulled 10.500 rpm at the end of the straight for an actual 167 mph. The track dropped onto a short straight coming off turn six, and there the Yoshimura Suzuki leapt up on its haunches every lap. seemingly ready to carry the front wheel nearly vertical until the next turn. The bike’s acceleration was fearsome in the lower gears, but that’s what you expect from racebikes. The shattering part was the way the machine gained speed even in the higher gears, making holding on a struggle and slamming the rider’s butt back into the stepped seat (which helps the rider hang on more than anybody not familiar with riding Superbikes might realize). Make no mistake, accelerating up to 167 mph in the length of a 5/s-mile straightaway is quite a rush.

It was significant how much better the motorcycle handled at Willow Springs when I met the Yoshimuras for a private test session after my recovery from pneumonia. For someone with experience racing Japanese box stock, production and Superbike Production class motorcycles with very few rides on GP bikes, riding the Yoshimura Suzuki is like being in heaven— albeit a demanding heaven, since the speeds quickly reached shorten distances and make everything on a given course happen much faster. The bike makes power in massive doses, accelerating hardest between 7000 and the 10.500 rpm redline but making good power from 5000 rpm and up. It isn’t peaky at all, and will charge out of a corner—or light up the rear tire—even at relatively low (for a racebike) revs. Shifting through the close-ratio fivespeed drops rpm less than 1000 with each upshift.

The brakes decelerate the motorcycle more violently than the engine accelerates it. The fully-floating rear brake is sensitive due to weight transfer, but is far more controllable than most rear disc brakes.

At Willow, the bike handled perfectly, stable when tapped out in fifth gear in a straight line and steady in both fast and slow turns. Grabbing too much of the always-available power at turn exits set up a rear-end dance as the wheel broke traction and skipped sideways in a series of little steps. Because of the racing pipe, beveled alternator cover and rear-set footpegs the rider doesn’t have to worry much about grounding out and crashing. But because the tires are so sticky and wide and the suspension so dialed in, it is possible at some tracks to drag the bottom of the alternator cover on the left and even the bottom of the points cover on the right.

Response to rider input is excellent, and it isn’t hard to make the bike turn or switch direction of lean in left-right turn sequences. If the rider backs off entering fast, sweeping curves the bike tends to turn in, as opposed to straightening up.

It's difficult to compare the Yoshimura Superbike to a stock Suzuki GS1000 street bike, because there really isn’t much comparison. A stocker is relaxing and easy to ride in its natural street environment; riding a Superbike fast on the racetrack is hard work because of the forces involved, even if the Superbike being ridden is the best in its class. It’s also unfair to compare Yoshimura’s Suzuki to a TZ750. The Yoshimura machine, although in its finished form isn’t much like a Streeter, does have its origins on the street, a limiting factor. The TZ750 came off the designer’s drawing board destined for the racetrack alone.

Instead, the Yoshimura Suzuki—and all Superbike Production machines—exist in a never-never land between stone stock street motorcycles and pure racebikes. In that middle category, the Suzuki is at the top of the heap, a position not easily attainable.

When I rode the Suzuki at Riverside it wobbled fiercely, yet at Willow the handling was faultless. The Yoshimuras believe that suspension is the biggest factor in handling, more important than frame or swing arm bracing or rigidity. Their Superbike’s suspension, which works so well when properly adjusted, has myriad possible combinations of air pressure, fork oil level, spring rates, damper rates, etc., etc. It must be tuned to each track and rider. The Yoshimuras hadn’t raced the GSIOOO at Riverside before I tried it, and so weren’t familiar with the required suspension settings for that track, and there wasn’t enough time during two shortened practice sessions to sort it all out.

With plenty of experience from testing at Willow, they knew where to start with the suspension and only had to make minor adjustments for rider weight and riding style. As a result, the bike worked.

Buying all the parts and making all the modifications is obviously only part of a successful Superbike. The most important factors are who puts it together and what they know.

The most important ingredients in the Yoshimura R&D Superbike are named Pops, Fujio and Suehiro.

What they know is what makes it work.

—John Ulrich