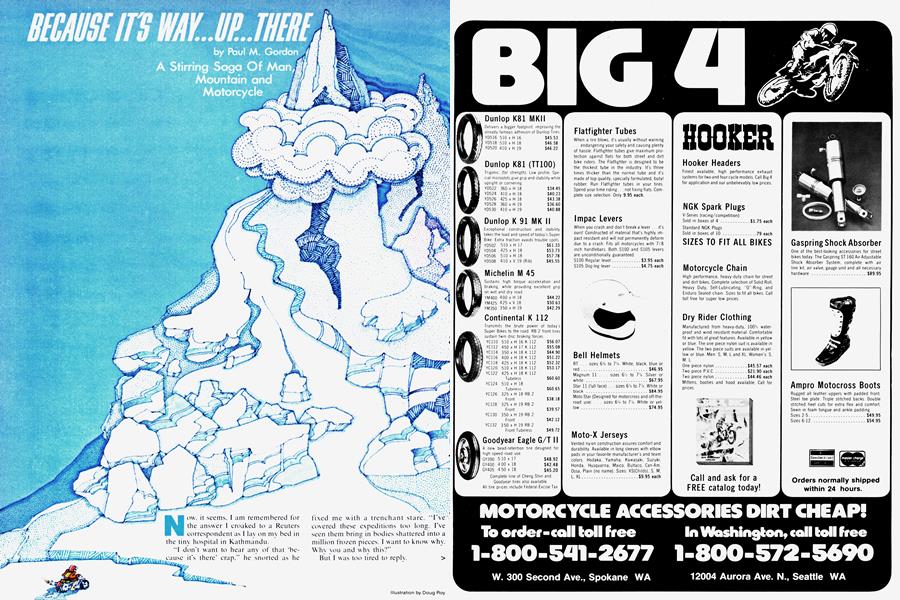

BECAUSE IT'S WAY...UP...THERE

Paul M. Gordon

A Stirring Saga Of Man, Mountain and Motorcycle

Now. it seems. I am remembered for the answer I croaked to a Reuters correspondent as I lay on my bed in the tiny hospital in Kathmandu. "I don't want to hear any of that he cause it's there' crap." he snorted as he fixed me with a trenchant stare. “I've covered these expeditions too long. I’ve seen them bring in bodies shattered into a million frozen pieces. I want to know why. Why you and why this?”

But I was too tired to reply. >

“Some men are born great.” he recited in a peevish tone, “some achieve greatness, and some have greatness thrust upon them. Which are you?”

I sat back heavily. With a deep sigh, I surveyed the events of the last months, the strange progression of struggle and conquest, ambition and pain. At that moment it all seemed somehow to be profoundly connected, tied to an almost insignificant event that had occurred ages ago, as if in another lifetime. This simple newspaper man standing earnestly before me, pencil poised above a yellow' notepad, spinning tape recorder scratching away, how' could he hope to understand? How could I make him see the subtle bond between the most bizarre assault on the world’s highest mountain and the sudden slippage of a cheap wag at a high school reunion in Akron. Ohio? How could he guess at the effect of that glistening skull upon my mortal soul? It was too absurd.

“Which are you?” he repeated quietly, respectfully.

“Me?” I laughed. Then I leaned forward and whispered into his microphone the quote that made his career:

“None of the above,” I said softly.

I was soaked right through when I swung my leg off the battered Bultaco and strode up the slippery stone staircase of the old high school gym. A large banner advertising the tenth anniversary reunion of the Class of ’68 was hung over the double doors. There were about a hundred creamy Cadillacs sparkling under the bright lights of the parking lot and not another bike in sight. At the door, a woman with a plasticcorsage teetering on the brink of her mountainous cleavage took my clammy jacket and ushered me inside.

I headed for the standup bar in the corner and was just lifting a stiff drink to my lips when a chubby fist smashed me in the back and a familiar voice boomed out: “Well. Nodrog. you old son of a gun you. Well, well.”

I didn’t have to turn around to recognize the presence of Bo Hudley. He had always been hard to ignore. Now he grabbed my shoulder and spun me around, sputtering a cloud of sweet, alcoholic vapor into my face.

“Well, well, well,” he said again, moving back a little. “You haven't changed a bit. not one eensy weensy bit. . . .”

I couldn’t say the same for Bo; his transformation was almost miraculous. The ten years since graduation had turned his baby fat to incorrigible fiab. A straining white plastic belt was cinched tightly around his bloated belly. His flaring buttocks were jammed inside a voluminous pair of polyester pants. He pressed my hand in an unctuous vise of pudgy fingers. The puckered wattles of his cheeks shivered hideously in a spasm of mirth.

“Well, well, well.” he said again.

“Hello there. Bo.” I replied. “How’s it hanging?”

. “Oh. pretty good, pretty good,” he said. “Can’t complain. Never thought I'd see you here though. What are you up to these days, still riding motorcycles and climbing mountains?”

“Uh huh.” I said shortly, and turned

away.

I was grateful when the band began to fill the awkward silence, writhing fiercely in a nostalgic medley of disco and raunchy rock. Bo leaned back from the bar and wagged his hips to the pounding backbeat, chortling obscenely. As he tipped his head to chug a beer, a seam in the lustrous layering of his hair suddenly parted and his gorgeous locks fell sideways, slipping from his scalp to reveal a gleaming dome, hairless as a headlight.

I stared in amazement.

At that moment I experienced what I believe the mystics call a revelation. The truth of my own mortality was suddenly revealed in every burned-out follicle of Bo Hudley’s bare noggin. We were growing old. everyone in this room. We were all gently gliding over the hill. Time had passed, was passing now, would eventually run out like a tank of gas.

I dropped my drink and bolted for the door. I felt a sudden intense ambition, an overwhelming desire to transcend my mediocre life and accomplish something unique before it was too late.

As I zipped up my jacket in the lobby, gazing thoughtfully at the deep crevasse beside the checker’s corsage, the kernel of an idea was sprouting in my brain, an idea so preposterous, so spectacular, so irresistible. that I shivered with delight.

I strode out the door and kicked the Bultaco to life. As I pulled on my helmet, a smile broke over my face: I would climb the world’s highest mountain, and I would do it on a motorcycle!

Preparation

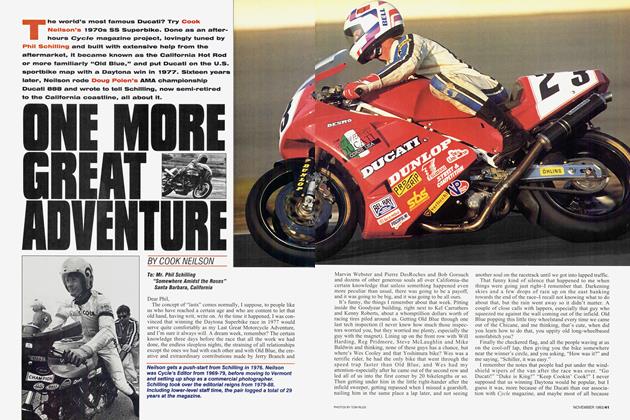

The finished product of months of labor and disembowelled bank book stood before me at last—a stripped-down Husqvarna 125. a sure-footed mountain goat of a motorcycle, handpicked for the ordeal, a low-end lugger hewn from rock, a nimble path picker and berm blaster—a bike to challenge the steep ice slopes, jagged cornices and sheer, almost vertical, faces that made up the awesome colossus of Everest.

The Husky was barely recognizable beneath a clutter of bizarre accessories: The teeth of a giant sprocket grazed the lip of the rear fender. Taut with antifreeze, a set> of balloon tires bulged from the alloy rims. The rear wheel was laced in a shackle of custom tire chains, bristling with sharpened crampon studs. A lightweight block and tackle hung from a clip on the rear fender. Helium shocks ran from the reenforced swing arm to the base of a saddle upholstered in Velcro. An altimeter and barometer winked from the tach and speedo nacelles. Coils of rope, Jumar ascenders and racks of ice screws and rock pitons were stacked neatly above the gas tank. Clipped to the frame near the carburetor in a clear plastic case, was a cluster of tiny, chromium oxygen tanks. Above 24,000 feet, they would be hooked to the air intake line. Finally, a large lever, connected by cable to the rear hub, was welded onto the skid plate near the left footpeg, as a parking brake.

The contraption looked like the bastard offspring of a midnight tryst between a lunar motocrosser and a hopped-up snowmobile. I was convinced, however, that she was the ultimate assault vehicle, built for the five mile vertical ascent to the summit of the world.

But the preparation of equipment for the climbing of Everest was nothing compared to the political red tape involved in getting near the mountain. After months of legal wrangling with the Nepalese and Tibetan authorities, it became evident that Everest had been booked in advance for the next ten years. The permit for the spring of ’78 was held by a team of German climbers.

So. Nothing more could be done. Circumstances had made the decision for me. Fate had taken a hand. With a thrill 1 realized that my expedition must involve only one man and one motorcycle, a silent and secret pilgrimage to the summit of the holy mountain that the Tibetans call “Chomolungma,” Goddess Mother of the Earth.

Assault

The Husky arrived, cleverly concealed in a nondescript wooden crate marked “HASHISH,” which passed unnoticed through customs in Kathmandu.

By late afternoon, I was jouncing along the trail that led deep into the heart of Sherpa country. Fields of wheat were carved in delicate terraces into the steep foothills. The rugged path meandered into valleys of thick, steamy jungle and over bleak plateaus of alpine scrub. Towering behind, marking the border of Tibet, were the jagged, snow' covered peaks of the Himalayas.

The eighty mile trek to the mountain, for most expeditions an exhausting month, was an easy two day ride on the Husky. On the evening of the second day I pitched a tent at the foot of Everest.

The great mountain, with its characteristic white snow'plume feathering the summit, reached up among the stars, dominating the horizon on a bright, moonlit night. It was freezing cold. I brewed a quick cup of coffee and fried a couple of eggs (over easy) on a flat, unfinned section of the Husky’s idling engine. Then I hit the sack.

The next day dawned clear and cold. A light wind rustled the tent flaps, a thick frost had embroidered the campsite in a fantastic filigree. The Husky exploded to life at the first kick. I suited up and packed the tent, took a long look at the jumbled chaos tottering above me. The Khumbu Glacier, guardian of the magic mountain, is a frozen river of ice, flow ing 2000 feet out of the heart of Everest. It is made entirely of fractured ice, falling steadily downhill at a rate of two feet a day in a crazy tumble of gigantic blocks called séracs, with deep crevasses between.

The ice fall is a sobering initiation into the impersonal violence of Everest. Since ’63, it has been the nemesis of many an expedition: in that year, a climber was crushed by a falling serac, his body never recovered. In ’72, another. In ’70 six Sherpa porters disappeared when a crevasse opened up beneath them.

But the Khumbu Glacier, like any river, has a shoreline. A narrow trough, banked and worn smooth as a bobsled track by the constant abrasion of the moving ice, runs up each side. Fear of dislodging the cornices of ice and snow which hang over the edges has kept climbers from these routes, forcing them to pick their precarious way through the deadly, shifting séracs.

But with the speed and handling of the Husky, I figured I could blast up the outside lane without too much risk of getting buried. It was not a time for weak measures. I pulled on my goggles, dropped the clutch and shot into the mouth of the steep, dark tunnel, under the shadow of the heavy snow.

It was the hairiest ride of my life. The brilliance of the headlight and the soft haze filtering through the overhanging snow' transformed the place into a twisting crystal hallway with a sloping floor of the deepest marble blue. Colored icicle chandeliers flashed past my face as I clung to the handlebars. The studded tire chains bit the slippery, spiral stairway, dragging me relentlessly upward. The Husky performed wonderfully, picking a line along the narrow trail, blasting off the icy berm in a burst of speed.

Then all hell broke loose.

I felt a deep shudder and took a quick look in the rear view mirror. What I saw made my blood run cold. The deep strum of the megaphoned exhaust, reverberating off the walls, was shattering the delicate foundations of the cornices. A deadly avalanche of snow and séracs was crashing down behind me. like the Red Sea closing on the armies of Pharaoh.

The Husky surged forward, front wheel clawing the air. engine snarling as a thin line in the floor ten feet ahead suddenly erupted in a deep Assure.

I held my breath and opened the throttle. The Husky leapt forward, shooting off the lip of the yaw ning crevasse, plunging to earth in the soft pillow of snow at the top of the glacier.

How long I lay still, suspended in the puffy whiteness, 1 do not know. When I rose at last, it was to find myself at the base of a huge snowfield lying in a protected cone between Everest and Lhotse, known as the “Valley of Silence.”

It was a spectacular and unearthly landscape. The stillness of the sheltered valley, with the two gigantic mountains on either side, was unnatural and awful. The silence of death hung over the place, the deep blanket of snow' absorbed every sound, except for a faint whistling. I dug the Husky out and lost no time in detaching the front fender, clamping it to a telescoping baron the forks. This would act as a ski to glide, unsinking, over the snow'. I kicked over the bike and began churning slowly up the valley, the treads of the back w heel throwing up giant rattails in the soft, deep snow.

After hours of slow ascent. I came upon the remnants of what had been the German expedition’s advance base camp. From the pile of littered equipment, already almost buried in a wave of snow, a trail led off to the left, out towards the jagged hump of the southwest face. I continued straight ahead, up the unbroken white sheet that converged on the vertical rock wall of the Lhotse face. This was the route travelled a quarter of a century ago by Sir Edmund Hillary.

The air at the top of the valley was thin and deathly cold. My shoulders and arms began to shiver uncontrollably as I huddled over the warmth of the humming engine. The sun had fallen behind the peak of Everest, plunging the valley into an impenetrable, desolate greyness.

At 24.000 feet I stopped beside a small depression in the snow and prepared to bivouac for the night. With frostbitten fingers. I pulled out the first of the oxygen cannisters and hooked it up to the carburetor. I barely had enough strength to check the plug and test out the winch before I pulled on an oxygen mask and fell into a deep, delicious sleep.

Dawn found me picking my way up the crags and cliffs of the Lhotse Face. It was slow going. Many times the narrow ridge on which I rode ended in a sheer drop. Moving on involved climbing ahead, anchoring a cable, and reeling the bike slowly forward with the winch. The frustrating toil of climbing and winching, climbing and winching, took hours.

By noon I had risen above the protecting peak of Lhotse. Now the battle with the terrible cold began in earnest. A steady blast of freezing wind whipped over the mountain, tearing at my body and sending the temperature plunging to 80 below.

The cold was affecting the performance of the Husky. The tires grated over the sharp rocks with a harsh, brittle sound, as if on the verge of shattering like glass. The cables were encrusted with a thick layer of ice. The engine coughed and sputtered every few minutes, requiring the installation of a new air flask.

By late afternoon, the plume of the summit was visible above the lip of a 100 foot cliff. With my last reserve of strength.

I set the parking brake and struggled upward. I had just finished setting an ice screw to secure the cable when my foot dislodged a piece of rock which began bouncing down the steep wall towards the bike. I watched w ith mounting horror as it glanced off the side of the engine, releasing the parking brake. The Husky began rolling faster and faster downward into the abyss. Just as the winch cable grew taut, a powerful gust of wind lifted up the dangling machine and flung it. like a crumpled piece of paper, up and over the top of the cliff. I climbed up and retrieved the bike, undamaged, in a sheltered cul-de-sac.

Now it was a clear run to the top. With the wind tearing at my back and my heart pounding, the white mass of Everest fell away below the footpegs and I was burning a small doughnut in the tiny junkyard of tattered flags and abandoned air cannisters on the roof of the world.

But it was a desperate victory. The words of Jim Whittaker, who stood on the summit in the spring of ’63. described my feelings perfectly: “Not expansive, not sublime.” he said. “I felt like a frail human being.”

I barely had strength to pull a tarpaulin over the bike and crawl underneath before I collapsed, overcome by exhaustion and hypothermia.

Still There

An intensely irritating clinking or tapping sound woke me from that sleep of death.

My first impression was of deep cold radiating from the marrow of every aching bone. I tried to turn my head and look around but my eyes could not see beyond the goggles of my mask and my muscles would not move. The sounds of muffled voices came to me. sounding far away, like conversation in a deep, underwater dream.

Slowly my brain began to decipher the reality of my position. A storm of ice flakes, called spindrift (the terror of climbers everywhere), had blown in under the tarpaulin during the night, filling up the chamber to the roof.

The chinking sound grew louder. In a few minutes warm hands reached in to remove my mask, hot coffee was forced down my throat. The German expedition had found the Husky and me. frozen solid in a giant ice cube of spindrift, suspended, like a fruit salad in aspic, on the summit of Everest.

I don’t remember much of the trip dow n the mountain, or the treatment in the hospital.

My most vivid memory is of lifting off in a warm jet heading for the States, the plane banking and turning East over the white waves of the Himalayas. I was sure I could see the familiar snow plume of Everest looming in the distance.

As we flew closer. I thought I could make out the faint circles of two spoked wheels almost hidden in the snow.