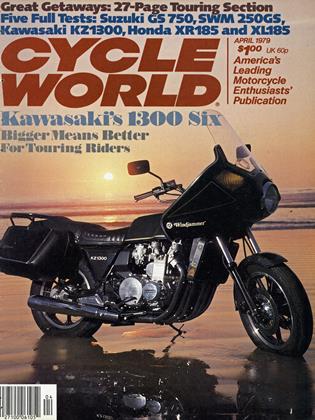

KAWASAKI KZ1300

CYCLE WORLD TEST

Enormous Bulk and Steamroller Power Combined Into A New Kind of Motorcycle: the Luxury Superbike

Evaluated on specifications alone, Kawasaki's 1300cc, liquid cooled, shaft driven, 120 bhp, 700 lb. Six would have to be the most out-rageous motorcycle ever built. The specifications alone gave new meaning to the word overkill. What’s most amazing about the incredible machine, though, is not its earth-mover-like power or its massive bulk, but how well it handles.

All of which makes it difficult to put the 44KZÍ300 into perspective. It is a motorcycle of contradictions. Because it has a big motor and six cylinders, it invites comparison with the Honda CBX. yet it is not a comparable motorcycle. Lest there be any confusion, the 1300 is a half second slower ^accelerating through the quarter mile. jL06 sec. fo.r-the Honda vs 11.93 sec. for ib^t.Mij^asaki, The number of cylinders is Warmly real cofltptfïison. The Honda is desrgnêdïor.spoj^Ü Wie Kawasaki designed to be a luxury Wiping bike.

There are comparisons to be made, but not with the CBX. Instead, the 1300 could be compared to the Honda Gold Wing or Yamaha’s XS Eleven, both big, refined, heavy touring bikes made for long distances on open roads with big loads.

The Kawasaki is that kind of bike. Only better.

Beginning in June, 1973, Kawasaki engineers began work on Model 203, which was to become a luxury high performance motorcycle. Various engine configurations were initially considered but the motorcycle was to have 1200cc and a shaft drive. The original 900cc Z1 had been introduced the year before and the sport market was considered well covered.

Six cylinders was considered the maximum number for the engine size and had an undeniable market appeal. At that time, the Benelli Sei hadn’t been introduced and the only Honda with six cylinders had been a GP racer made in a previous decade. While a V-Six, like the Laverda endurance racer, could be more compact, Kawasaki had more experience with inline engines and could design an inline Six sufficiently compact to fit a motorcycle.

That’s where the liquid cooling comes in. Although an inline Six, with cylinders lined up across the frame, could be air cooled adequately, liquid cooling could make the engine more compact because less room is needed between cylinders. Liquid cooling, of course, also has merit for touring bike use: it insulates against mechanical noise, making the bike quieter; it increases longevity through precise control of operating temperature; and it allows more efficient running by holding temperatures constant and higher under normal operation than is possible with an air cooled engine.

Because the Six was to be a touring bike instead of an all-out sport bike, the design is compromised more toward touring than sport in a number of ways. Because ultimate power potential wasn’t needed, the engine is decidedly undersquare with a 62mm bore and 71mm stroke. An oversquare engine has more piston area, more room for valves and lower piston speeds, all of which contribute to higher horsepower, but the undersquare engine is narrower and, all other things being equal, produces more low-end and mid-range power. Just the ticket for a touring bike.

Most of the design innovations narrow the engine across the cylinders and head, rather than at the crankshaft. While Honda moved the alternator and ignition behind the crankshaft to keep the bottom of the CBX Six narrow for improved cornering clearance, Kawasaki left the alternator on the right end of the crankshaft and mounted a torsion damper/flywheel on the left end of the 1300’s crankshaft. The weights help balance the Sixes’ cyclical vibrations but don’t help cornering clearance.

To keep the crankshaft short, there’s only one drive chain, a 32mm Hy-Vo, which drives a jackshaft directly behind the crankshaft. There is no cam chain from the crankshaft. Instead, a 10mm Hy-Vo chain runs from the jackshaft to drive both cams.

The incredible sophistication of the 1300 is apparent in the drive system. Once power is transmitted to the jackshaft, it goes in two directions. To the right side, the power flows through a spring-loaded camtype damper to the 40mm Hy-Vo chain which drives the mammoth clutch.

To keep the jackshaft narrow, the damper drives an inner shaft which is splined to the outer shaft which drives the clutch drive chain. On the left side of the primary drive chain is, first, the cam chain, then a bearing, then a roller chain which drives an auxiliary shaft, and finally a nylon spur gear which drives the oil pump. The roller chain is the only one of that type in the engine.

The auxiliary shaft, which runs directly above the jackshaft behind the cylinders, is just as busy. It is driven at its left end and drives the pulse generator of the transistorcontrolled breakerless ignition through a nylon spur gear on its right end. In the middle of the auxiliary shaft is a bevel gear which drives a tiny shaft running forward between the center pair of cylinders and which has the waterpump mounted on its forward end.

To keep the auxiliary shaft drive chain and the cam chains taut, there are spring loaded, ramp-type automatic cam chain tensioners on both chains. There is also a cover plate on the left-hand side of the auxiliary shaft housing which can be removed, allowing the drive chain to be disconnected so that the cylinders can be removed.

The same kind of sophistication continues throughout the driveline. A rubber block-cushioned clutch drives the transmission mainshaft. On the left end of the transmission output shaft is another camtype damper, this one tensioned with four large spring washers instead of the coil spring used on the jackshaft’s damper.

Unlike the first damper, power flows from the outer drive shaft, through the damper, to a splined inner driveshaft which runs through the entire output shaft and drives the spiral bevel pinion on the righthand end. The front pinion gears are held in tapered roller bearings, as are the driveshaft gears. The final drive gears are part of the transmission and lubricated with transmission-engine oil instead of being housed in a separate case and lubricated with a heavier oil.

Novelty doesn’t end with the power train. Behind the cylinder head, where six separate carburetors would interfere with a rider’s knees, there are three two-barrel carbs. Three carbs are narrower than six, even though there are the same six barrels. Venturi size is 32mm on the Mikuni CV carbs, noticeably larger than the venturi size on That Other Six. Because the three carbs are mounted so closely together, the intake ports in the head for the outside cylinders are noticeably longer than the ports for the center cylinders. Carb settings, however, are the same, and Kawasaki says the difference in port length doesn’t cause any problem.

The cylinder head is mostly conventional Kawasaki with two valves per cylinder (34.5mm intake and 29.5mm exhaust) operated by twin cams through bucket followers with shim adjusters. Valve lift is 8mm on intake and 7.5mm on exhaust. What’s unusual about all this is the 9.9:1 compression ratio. Kawasaki ushered in low compression motorcycles with the Z1 in 1972, the first high performance motorcycle designed to run on regular gas. The Z1 also had a crankcase breather to reduce emissions, a system later adopted by all motorcycle manufacturers.

All of the modern Japanese street bikes have been designed to run on low lead gas, even Honda’s CX500 which has a 10:1 compression ratio. Kawasaki has even recommended use of no-lead fuel in most of its motorcycles. Now Kawasaki introduces a motorcycle with high compression and which is designed to run on premium gas, but which the engineers tell us will run on low lead gas if needed. With the increasing difficulty of finding high octane fuel, it’s important that a touring bike be able to run on regular grade gas.

Already mentioned was the crankcase breather Kawasaki introduced seven years ago. On the 1300, there is an emissions package designed to meet emissions regulations without sacrificing performance or ease of use. Besides the breather and inductive ignition are carbs designed for more accurate mixing but not lean running, as some motorcycle carbs are. Instead. there’s an air suction system which burns hydrocarbons and carbon monoxide in the exhaust system after the gasses have left the combustion chamber.

A fresh air line runs from the airbox, through a vacuum operated shut-off switch, to the housing on top of the exhaust cam. Once in the exhaust cam cover, the air spreads out to six small ports in the head, via six reed-type one-way valves. The ports lead to the exhaust ports in the head, just behind the valve seats, where the fresh air allows the hot exhaust gases to continue burning, cleaning up the exhaust.

The fresh air is sucked into the exhaust ports by the flow of moving exhaust gases, rather than being pushed into the exhaust ports by a pump, like the systems used on automobiles, so there is no power loss for the system. Because the exhaust leaving the combustion chambers can be “dirtier” than it could be to meet emissions laws, the carbs can be set for more power. The vacuum-operated shut-off valve prohibits the fresh air from entering the exhaust ports during deceleration, eliminating backfiring. It’s an excellent emissions system and one which will be used on all the large Kawasaki street bikes, 650 to 1300.

To check emissions from each cylinder on each motorcycle, there are small holes in each of the six exhaust pipes, each one plugged with a small bolt. By checking the emissions from each cylinder, rather than from the exhaust of all the cylinders, the motorcycle can be tuned more precisely.

Completing the engine package on the 1300 is the cooling system. Much like an automotive system, the aluminum radiator mounts in front of the downtubes and has an electrically-operated fan mounted behind the radiator. Made with printed circuits, the fan motor is flat like a pancake. A thermostat controls engine temperature up to 207° when the fan is triggered by a thermostatic control. A reserve tank holds overflow and is easily accessible on the left side of the 1300, behind the transmission.

Unlike the fans on other liquid cooled motorcycles, the 1300’s fan will turn on after the engine has been shut off. When the wáterpump quits circulating coolant, the thermosyphon effect still circulates coolant and the internal components will continue to be cooled. That's why the coolant will heat up when a liquid cooled engine is normally shut off. To hold down engine heat and minimize carb percolation the 1300’s fan will come on when the coolant reaches 207°, even though the engine is off. Yes, the 1300 rider will be told by other people that he left the engine running when the fan kicks in.

No less impressive than the engine is the frame. It’s a cradle-type, double downtube of extraordinary strength. From the steering head, there are double thickness downtubes, 37mm steel tube over 34mm steel tube. Halfway down the front of the frame the outer tube ends and the 34mm tubes wrap under the engine and back to a cast iron junction behind the transmission. Looking like a frame member from a Caterpillar tractor, the cast iron junction wraps half way around the lower frame tubes, top tubes and lower back tubes of the frame, as well as holding the swing arm pivot in tapered roller bearings.

The swing arm has square steel sections, welded together with cast axle mounts and gusseting in front extending to within a half-inch of the rear tire. It’s the beefiest swing arm in motorcycling, and not by a little bit.

In front are 41mm fork tubes held 8.25 in. apart. Here we have another difference in engineering opinion between Honda and Kawasaki. Honda engineers tell us fork tube diameter is not especially important in getting a rigid front end. but positive axle location is, so That Other Six gets 35mm fork tubes and four-bolt axle clamps . . . and wobbles. Kawasaki uses the largest stanchion tubes available, and leading axle forks which hold the axle firmly ... no wobble. The forks have both coil springs and air boost, normally using 8.8 psi. Travel is a long 7.9 in.

Rear suspension comes from conventional coil springs, constant rate, with five preload settings. There is no adjustable damping, as on the latest Suzukis and Yamahas.

The brakes are consistent with the rest of the motorcycle: they’re huge. Twin front discs are 11.9 in. in diameter with an effective diameter, Kawasaki says, of 10.2 in. The single rear disc is 10.8 in. across, with an effective diameter of 9.8 in. All three discs are drilled in an irregular pattern which Kawasaki says reduces brake squeal. Disc pads are made of a sintered material for better wet weather braking performance.

Special features abound on the big Thirteen. The headlight is a 55/60 watt rectangular halogen lamp with a bright. controlled beam and lots of light. The tail/ brake light uses two bulbs. Dual horns, a high and a low note, are probably the loudest motorcycle horns ever made and ought to be available on every street motorcycle.

There’s no vacuum operated fuel petcock. Instead an electrically-operated fuel switch mounted on the engine shuts off with the ignition. Kawasaki says the electric switch gives more positive fuel shutoff than a vacuum petcock. A couple of the Italian manufacturers (Moto Guzzi and Laverda) have been using electric petcocks for several years with generally good results. but it’s difficult to argue the merit of something which does in a complicated way w'hat a simple device also does.

Brake master cylinders, front and rear, are solid aluminum pieces with small, round sight gauges for fluid level. Hand controls are new on the 1300. The left hand control unit has a collar adjacent to the grip which rotates around the handlebar to switch beams. There is no switch to turn off the lights. The closest rocker switch on the left control turns on the four-way flashers The next closest, a tiny red rocker sw itch, shuts off the turn signal cancellers. Further away is the signal Tight switch and at the bottom of the large pod is the horn sw itch. On the right control is a kill sw itch and a starter rocker switch which was defective on the test bike and would only work when pushed half-way in.

Clamping the handlebars to the triple clamp is a rectangular cap. It is attractive and does the job of holding the bars. Above the cap are the instruments, set into, and in front of, a fashionable rectangular pod. Below the instruments are the ignition switch which incorporates the steering lock, neutral, high beam, oil pressure and headlight failure warning lights. Between the 160 mph speedometer on the left and the 11,000 rpm tachometer on the right are a gas gauge and temperature gauge.

Under the seat is one of the larger tool kits ever seen on a motorcycle. The wrenches are polished. There are Allen wrenches and an offset box-end wrench which will, when combined with the spark plug wrench, remove even the center two plugs without having to remove the gas tank, although it’s not an easy task. There are no tire tools, but there is additional storage room behind the seat in the tailpiece.

Behind a pivoting corner of the lefthand side panel is a lock, operated by the ignition key, which opens the seat latch but also can shut off the power. That makes two ignition switches. It’s convenient to use, does add some theft prevention and doesn’t get in the way when not in use. Admittedly, a professional thief isn’t going to be prevented from stealing the 1300 because of a second ignition switch hidden behind a side cover, but if the second switch doubles the amount of time it takes to steal the bike, it’s worthwhile.

Something not found under the seat, and which has become as common as the stepped seat, is a helmet lock. It’s the first big Japanese bike we’ve seen in recent years without one. The person who regujarh uses, a helmet lock will feel sKortchanged but there is a reason for its absence. The 1300 is intended as a touring bike and as such will be carrying saddlebags for many owners. The saddlebags usually interfere with helmet locks, so the 1300 doesn’t have a helmet lock. Considering how simple it would be to add a hooktype helmet lock under the hinged seat, it would be preferable if Kawasaki installed one.

If the technical details of the 1300 seem like overkill, a ride on the beast is underwhelming, not because the bike doesn’t work well, but because it doesn’t work as poorly as a 700 lb. motorcycle should work under conditions not made for 700 lb. motorcycles.

Physically, the 1300 is imposing. While Honda has chosen to emphasize all six cylinders of the CBX with the open frame and six shining exhaust pipes, Kawasaki impresses people with its size. The KZ 1300 is not even perceived as a Six. but as a 1300. that is, as The Biggest. Several times during the test, motorcyclists would approach the test rider and ask about the 1300. usually asking howmany cylinders it had. Because the flat black radiator hides the exhaust pipe-cylinder head area, the six cylinders aren’t immediately apparent.

Turn on the ignition, lift up the choke lever on the side of the left carb, hold in the clutch lever, touch the starter button, and the hushed whir of six pistons pumping out the smoothest power in motorcycling burbles out of the 6-into-2 exhaust system. The 1300 can be instantly shifted into gear and ridden off, with choke or without, it’s that mild mannered.

Clutch pull is moderately light, the shift lever moves down one notch so easily it’s hardly felt and without a clunk, and the Thirteen glides elegantly away, regardless of throttle opening. The bike can be shifted at 2000 rpm or 6000 rpm, it makes no difference to the transmission, and shifts are smooth, silent and never missed.

Never has any motorcycle, particularly such a big motorcycle, shifted so effortlessly. The last time a bike shifted nearly this easily it was the prototype CBX and the production models are nowhere near as impressive. The test Zee, being a production prototype, also may be better than future production models, but that’s speculation.

Shifting is not one of those things w hich need be done often on the Kawasaki. There is no torque curve to speak of. It’s a straight line. Kawasaki says the 1300 puts out 85 ft.lb. of torque at 6500 rpm. Only the Harley-Davidson 80 approaches that figure. What Kawasaki doesn’t say is the amount of torque produced at 2000 rpm which, no doubt, is nearly as impressive a figure. Multiply all that torque times lots of revs (8000 rpm redline) and the result is horsepower. Lots of it. A claimed 120 bhp at 8000 rpm. Enough power to dissolve a rear tire in a couple of thousand miles of spirited riding or a short day at the drag strip.

While it’s true that the fastest Suzuki, Honda, and Yamaha can accelerate through the standing start quarter mile quicker than the Kawasaki, the Thirteen carries considerably more weight than any of the other megalocycles. It weighed in at 709 lb. with a full tank of gas, or 692 lb. with a half tank of gas. That weight hurts most off the line where the 1300 is slower than the other fast ones. Even during impromptu roll-ons at the 1300 press preview the 1300 lost to the new KZ1000 up to 90 mph where the enormous power overcame the weight disadvantage and wind resistance became more important than mass.

Gearing doesn’t help the big Kawasaki win races. It’s geared high so the motor will be turning over slowly while the bike cruises down the interstates. At an indicated 70 mph the engine is running at 4000 rpm. The gearing is substantially higher than that of even the other big Japanese torquer, the Yamaha XS Eleven. That hurts the 1300 when it comes to acceleration or even hill climbing or highway passing, when compared to the Eleven but still is superior to just about any other two wheeled vehicle.

What enables the KZ to overcome the very tall gearing is that beefy clutch. During 16 runs at the drag strip, enough to destroy the last half of a rear tire, the clutch didn’t even need to be adjusted. There was no slip, no problem, just engagement directly proportional to the position of the clutch lever.

Weight is the single penalty for the plush luxury and anvil-like strength of the 1300. But because the weight is in the right places, in the frame and suspension, it is a small problem once out of the parking lot. Moving the Kawasaki around at low speeds or pushing it around in a garage is enough to convince people of the need for power steering on motorcycles.

Above, say, 10 mph the clumsiness is gone, replaced by confidence. It’s not a confidence of precise steering, because the giant 1300 has a slight hunt at the bars at low speeds, perhaps caused by the slight offset of the two wheels. Rather, it’s a confidence of a stable motorcycle, utterly predictable and without the dread wobble which plagues some other fast motorcycles. This doesn’t, however, make the Thirteen a pleasant motorcycle for aroundtown riding.

On the interstate the Kawasaki just hums along, not bothered by sidewinds or hills or vibration or noise. But take the 1300 into the hills, where big touring bikes are supposed to slow down, and the surprises begin. It’s easy to build up the rhythm going through alternate left and righthanders, until the tab on the left-hand side of the centerstand begins scraping and the hind end of the right-hand muffler touches. The Kawasaki isn’t scraping because it is hurting for ground clearance; it’s not. It’s scraping because the motorcycle is hurrying through the bends swiftly and securely, allowing the rider to lean it over just as far as it will go on each corner.

The 1300 is not a road racer. The ground clearance isn’t that good and it’s too heavy. It’sjust a supremely stable high speed road bike. The only way we got a wiggle out of it was to ride through fast (80-90 mph) bumpy sweepers and then the effect was tiny and auicklv damned.

Cornering precision isn't free, however. It requires stiff rear springs and shocks which give a firmer ride than many touring riders are accustomed to. Kawasaki offi cials say the final KZ1300 may get slightly softer rear springs to improve comfort, but that may hinder the handling. The front forks are fine the way they are. Used with the recommended 8.8 psi. they were mildly soft but controlled. A higher pressure would improve cornering clearance.

Overall comfort offered by the 1300 is good, but not outstanding. The seat is wide and relatively long but it's firm and tiring after a half day in the saddle. Coupled with the stiff rear springs, more harshness came through than should. The passenger portion of the seat slopes down toward the rider, making a passenger uncomfortable on long rides. FOotpegs for the rider are about two inches farther forward than is normal practice making for a more Harley-like seating position. The handiebars are wide and bend back moder ately, making a fine seating position behind a fairing or windshield but a tiring position without any other protection.

Controls on the KZ are a mixture of good and bad. The brake lever takes less pressure to stop the behemoth than seems normal but control remains good. Switches are the big problem with the signal light and horn switches just too hard to reach because of the overgrown left control pod.

There is no vibration or noise to annoy a rider or passenger. Even with a fairing, which bounces gear noise of some bikes back onto the rider, the 1300 was silent and smooth. The most uncomfortable part of the motorcycle, however, was the gas tank. Kawasaki did shape the tank to be nar rower at the rear section between the rider's knees, but the tank is still too wide at the rear which cuts into the rider's thighs too much. Cutting the tank down smaller would reduce the 5.6 gal. fuel capacity too much. Riding on the open road returned 44-45mpg, a reasonable figure. With the 5.6 gal. gas tank cruising range is over 200 mi. under normal use,which is adequate.

The tank and overall style of the Ka wasaki drew quite a bit of comment, not only from staff members but others who saw the bike. While the bike looks better than early pictures, it is not especially graceful. The extremely wide tank and radiator cover up the engine so much as to hide the six cylinders. The color, a deep bluish green doesn't ad4 any excitement, either.

Another problem is caused by the wide tank. Most fairings currently in production aren't wide enough to fit around the tank and it will take the aftermarket several months to redesign fairings to fit around the tank. Otherwise, accessory mounting is straightforward, the rear end being partic ularly suited to carrying heavy loads.

Ká'wasaki knows tile 1300 wIll appeal to touring riders, people who carry lots of weight and lots of accessories. As soon as the bike is released for sale. Kawasaki expects to offer Kawasaki-made fairings and saddlebags for the bike.

Load carrying capacity of the bike should be excellent with the new-style Dunlop Gold Seal MT9Q-17 rear tire and MN9O-l8 front tire. Load capacity of the tires is 810 lb. for the rear and 640 lb. for the front. Kawasaki says the rear tire should last 6000 miles under normal use, which is not especially good. but hard use can shorten that figure considerably.

What Kawasaki has produced is a new kind of motorcycle. not quite like anything else made. Twenty-five years ago there was the Ariel Square Four which was a similar kind of motorcycle but nowhere near as good. Today there are motorcycles with more speed, but not with the same com bination of power. strength, comfort and handling.

The sophistication is incredibte. the size is enormous. What we have here is an incredible hulk.

KAWASAKI

KZ1300