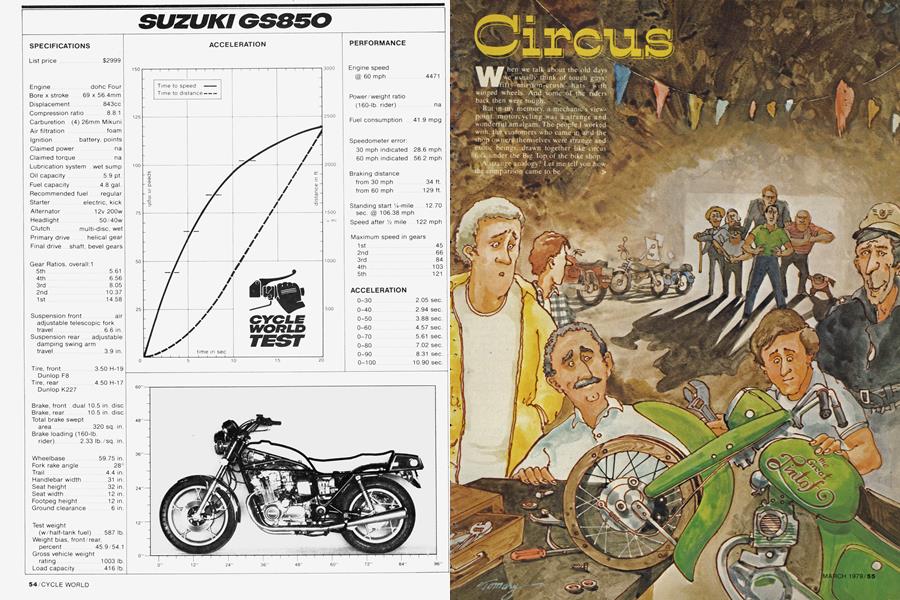

Circus

When we talk about the old days we usually think of tough guys: fifty-mission-crush hats with winged wheels. And some of the riders back then were tough.

But in my memory, a mechanic’s viewpoint. motorcycling was a strange and wonderful amalgam. The people I worked with, the customers who came in and the shop owners themselves were strange and exotic beings, drawn together like circus %ik. under the Big Top of the bike shop.

A rrange analogy? Let me tell you how the com parison came to be . >

You know the sort of people who hang around bike shops. And you know what circus folks are like. What if they got together?

Jim Wills

One summer day 1 had an early Sixties Norton engine apart all over my work bench, glistening with the dull, sand-cast sheen of its pre-unit. pre-Neanderthal genius. I began to assemble it quickly and easily, knowing from long practice that those early motors responded best to force. Next to me. John, “The Vultch." worked on a Harley, using large tools, singing his only song: “Battery acid and a rat-tail file, do dah, do dah . . ." He was wonderful; drove a knucklehead, really wore one of those winged wheel hats and the ancient motorcycle jacket with all the useless zippers. Ón the back was painted a lurid vulture, cracked and faded bv sun and time, but apparently crushing a Triumph in its powerful talons. In many ways John was a genuine throw-back to the 1950s, and I sometimes had the uneasy feeling that he had memorized the dialogue of “The Wild One."

Despite all these things, or maybe because of them, John was a brilliant mechanic. He worked at the shop only part time. Most of his energies were spent machining tiny parts out of exotic metals for N.A.S.A. I had known him a good many years and he had taught me much. It was John who kept my beleagured Honda CR77 competitive with the Yamahas of the day. John was a man of contradictions, and, if anything at all, he could be relied upon never to be serious about anything. Still, sometimes I wondered.

Today was particularly exciting for me, because at last it seemed that Rickman was not really out of business, my deposit had not been stolen, and finally 1 could drop the Bonneville motor 1 had so carefully worked and whose insides were at least partially due to John’s genius on the milling machine into a bright nickel-plated frame. From there it was an easy step to become a rich and famous road racer, scourge of the KRs. Not only that, but 1 might be able to pay the rent and next year’s tuition. (It is a well known fact that motorcycle mechanics work for parts only; money never changes hands.)

My fantasies were abruptly ended by the ringing of the shop phone. It was an incredible thing: greasy, paint spattered, and wrapped with once white adhesive tape from the first aid kit. Once more I had to peer at it awhile to find out which was the mouthpiece. Pete, the parts man, was on the other end of the line saying with a nervous snicker that he had a hot one for me holding on an outside line. I wasn't surprised that a new customer would ask for me by name, because I had a reputation in the city for fixing out-of-production and odd-ball problems, like, for instance, making magnetos work or Ducati lights stay on. When the connection was made, my initial reaction to the new voice was typical of any enlightened easterner, and I thought, well, a foreigner, for his English had the thick vowels of some Slavic language. “Hullo, I been told you fixes old motorcycles, right?" “Yeah, right, whatcha got,” I replied. As best he could, he described the old 150cc Honda, the one that years before came w ith a tiny plastic w indscreen bolted just above the square headlight. Even when it was in production it was w hat's called in the trade a rat, but as a flat-rate mechanic I needed all the work I could get to barter for Rickman frames and roller cams. Anyway, 1 agreed to make it run for him. but his promise to be right over with the thing was tempered w ith a bit of hope that maybe he would forget or lose his way.

John was a man of contradictions; he often told me that the Japanese motorcycle was the Anti-Christ.

At any rate. I forgot about it, since it was lunch time, and after locking up everything I owned in my impregnable SnapOn tool chest, this to prevent the lighter than air problem that tools have when you're not looking at them. I turned round to start out of the garage. “The Vultch” gimped over, he had one stiff leg from an old hill-climb spill, put his arm around my shoulders and began to tell me once more about how he had seen the light one day speeding along an Allegheny Mountain road. Now he had religion, so he said, and gave out those little pamphlets that look like they're printed on brown paper bags w ith bold type saying REPENT. John was a man of contradictions; he often told me that the Japanese motorcycle was the AntiChrist. In fact, he was fond of shooting used spark plugs, sharp end first, at a poster of a 305 Honda Hawk that hung on the wall. I was never sure John was serious, this was certainly inconsistent with his care of my CR77.

We started out of the garage; it was ancient, long, and narrow (the cement floor a mosaic of Oil Dry that had been there since 1952). These were the days before specialization, and the shop was lined on each side with files of bikes, everything from 50cc Benellis to 100-in. strokers. Looking out the door, we had a view of the vacant lot that was our practice dirt track. Unfortunately, it was also used by the shop manager, Julius, to do a bit of Castrol can plinking with his .22. You had to be pretty sure that he wasn't around when you started practicing, but if you weren't, it was a fine way of developing quick reflexes.

Before going to lunch. John and I had to collect our fellow workers, because it was traditional that we all ate together. Claus, the BMW man. came originally from Hamburg. Six-six in his socks, he began as a bulldozer mechanic and was famous for sledge-hammer remedies on bent twin cranks. He was a man of great finesse, an accomplished sidehack racer. He worked in another section of the shop with his passenger, the slight, dark Georg. An Arab from Jerusalem. Georg was happiest with meticulous, endless, and finally successful fiddling with the most complex problems. He reminded me of a watchmaker, and. in fact, could even make Velocettes start on the first kick.

The last member of our lunch time crew. Pete, was to be found as always in the parts room counting washers. The parts room was a separate building, an old house, wfith fenders and gas tanks in the bathroom, engine cases in the bedroom, electrics in the parlor. Pete knew exactly how many of everything he had. He loved those parts like a mathematician loves a sharp pencil, and he was a bit annoyed when the mechanics used any and made him alter his tally sheets. Washers were his favorite: “See that box, man? No. not that one. the other.” 1 had been looking 5 degrees to the left. “It has 453 10mm w'ashers in it.” Pete’s emaciated body was hidden as usual somewhere within a T-shirt and jeans that would have strangled a human. Extremely nervous and easily exasperated, Pete was an excellent ifjumpy parts man. Amazingly. though, at the track he was dead calm, deliberate, and extremely fast; a difficult opponent in a corner. He was our pipeline to secret factory information; he always seemed, somehow, to know of new models, new' innovations before anyone else.

With our retinue complete, we gimped and strutted, jumped and pounded up the street towards McDougall's Bar& Grill. In most big cities in the east, the Bar& Grill is the hub of neighborhood life. McDougall’s was no exception, serving fine delicatessen food found nowhere else and the worst beer in the world. Our group should have been unusual there, but McDougall's was a motorcycle bar. Anytime, day or night, long rows of bikes stood outside, and the talk, sometimes heated, ran on about the relative merits of Harleys and Triumphs or the growing Yellow Peril. Nevertheless. McDougall's was a peaceful place. Under the blue glare of the 26 channel television, everyone seemed to fit: the outlaws, the off-duty motorcycle cops, the little old ladies with shoppi eags, and even the bewildered local non-bikers. McDougall's did a good business with its motorcycle trade and the attraction of a prominent baseball scoreboard given out by some brewery which was always covered with long rows of numbers, none of which had anything to do with baseball.

This day Pete, in a tone of high conspiracy, called us all into a dark corner booth to reveal the coming of the mighty Honda Four. Claus wondered how low the motor could be dropped: Georg wanted to know how the carburetors worked: I thought of my now possibly slow Triumph, and John raised his eyes to the ceiling. It was, he said, the beginning of the end, proceeding to discuss the possibilities of fuel injection.

I am nostalgic about McDougall’s. It was there I first heard of multi-cylinder Armageddon; it w;as there that I first thought of the analogy between motorcycling and the circus. Up to this time, though, it was only a partially formed analogy. An event of the first magnitude was necessary to crystalize it into a Theory. ET

The blue Ford panel truck I saw parked in front of the garage when we returned from lunch had nothing at all extraordinary about it, but how was I to know' what it contained? By my bench, I met the man with the telephone voice, yet his looks didn't quite match his accent. He had a noble, nearly patrician face only slightly marred by a very recent black eye. His shiny, thin, black Italian shoes matched the glitter of his frayed sharkskin pants and the continental green of his knit shirt. He was holding one of the Vultch's pamphlets at arm’s length. Despite his looks, he turned out to be Hungarian, and he explained that his bike had a funny habit of losing power at odd moments and that this could be extremely dangerous. I nodded, but didn't quite see why he was all that worried about it.

“O.K.,” I said, “let’s have a look.” Imagine what I thought, then, surrounded by hundreds of normal, or at least near normal. bikes when the Hungarian Count wheeled this thing in. The little Honda was brush painted a vivid metallic green and its tires had been replaced bv wooden circles bolted to the rims. Rolling across the cement and Oil Dry it reminded me of the sound track from “Ben Hur”. Honda 50s with ape hangers began to seem like the most usual thing in the world. “Wow.” I thought, “this nut drives a bike with wooden wheels.” Only when I noticed that each wheel had a three inch groove lined with rubber did I begin to understand why he was so concerned about losing power. “Ah, look, ah . . .” “Lintof.” he said. “Good, ah. well, look here Lintof, if you don’t mind my asking a personal question, just what exactly do you use this thing for anyway.” I had learned to be circumspect when handling customer relations. “Simple." he said. “Simple,” I thought. “Holy Cow.” “Simple, I ride it on the highw ire in the circus. I am the Great Lintof. w ho rides the highwire unafraid, without nets, seventy-five feet above the floor of the Big Top.” I was agog. The whole speech was given in a booming voice and said quite flaw lessly as if memorized from a billboard or one of those circus posters slapped on fences with huge brushes. Claus had followed the bike in from the street and stood towering over me and Lintof, slowly rubbing his chin. Georg swung himself around a corner, so that his head was perpendicular to the door post, his look saying “Huh?” John w;as circling the circus bike humming a low “do dah. do dah.” Luci had escaped.

Pete, in a tone of high conspiracy, called us all into a dark corner booth to reveal the coming of the mighty Honda Four.

“Look Mr. Mechanic” (in his continental formality he actually called me Mr. Mechanic), “I can't do my act. because this thing won't run. I must do my act, fix it.” His last sentence was thickly laced with dire warnings of what w ould happen to me if the bike didn’t run and soon, but confident of my ability, I had little fear. Well, relatively little, anyway, since Lintof pared his nails with a long, and from its looks, quite sharp stiletto. I admired the man. not just his bravery, but also his showmanship, and, certainly, his incredibly advanced insanity. A Theory was born, the Lintof Theory: motorcycling was not only like the circus, it was the circus. Road racing was nothing compared to this. The details remained to be worked out; which came first, the circus or the bike? >

Predictably, the thing simply would not fix. Years of unorthodox solutions to common problems in the remotest corners of the world had left their unmistakable mark. The wiring harness, wrapped in band-aids, sprouted illegal wires trailing off into the remotest parts of the pressed steel frame. 1 don't think it had a coil. The pistons rattled in the bore like marbles in a coffee can. Pete told me there were only three fourth-over rings for this model in the entire world. It had mysterious ticks and rattles, the swing arm was held on by stove bolts. Test riding wits out of the question. The miracle was that it ran at all. but make it run right I could not. After days of threatening Lintof phone calls, I hadn't noticed before how much he sounded like Basil Rathbone, I was prepared to roll it into the street and leave it for the termites. The final phone call went something like this; “Listen, son-of-abitch Mr. Mechanic, fix it by 2 p.m. or 1 come with my friends to fix you." Seeing images of Paul Newman in the alley w ith his hustler's fingers broken. 1 made involuntary helpless noises.

After another lunch, this one with the Vultch holding forth on the moral evils of the overhead camshaft, it had something to do w ith the presumption of order coming from above rather than below. 2 p.m. finally came and right on time the blue van arrived at the garage door. The whole circus piled out; it was too much to think about really. The Strong Man w ith shaved head, red and white striped T-shirt that probably would have fit Pete; the ridge of muscle between his eyes told me he was not a nice person. Next came the midget, looking mean, carrying a kid's size baseball bat. wearing a Tyrolean hat. and smoking a cigar nearly his equal in size. The carnev barker with no teeth, the lion tamer with plastic sideburns, the Giant looking ponderous, thev were all there, Lintof in the lead.

I was convinced then that the circus came first. Motorcyling was spawned by a carnival act. I couldn't take my eyes off them, what a show, how could anything top this. Suddenlv, though, the scene began to shift. It started with the Vultch, quoting Revelations, picking up the air hose with one hand and expertly loading a spark plug from his ammo box with the other, then came Claus with his sledge, and even the silent Georg looking offensive. saving nothing. Julius arrived with his Castrol gun; Luci eyed Lintofs shoes like a bandito from the “Treasure of Sierra Madre." Pete bounded around the corner yelling. “Wait. wait, not yet. wait till I see."

Pete's were the first words spoken, and everyone seemed to freeze, not knowing what to do. Once more the scene changed beginning with the Vultch. He dropped the air hose, grinning and humming, and started gimping around distributing pamphlets. Salvation, said he. had to do with multi-speed transmissions and the tubular frame. Claus went ofi' in a corner with the Strong Man and the Giant. Georg finally spoke to the lion tamer. Luci discussed hats with the midget, and Pete interrupted Claus to talk T-shirts with the Strong Man. Julius and the carnev barker exchanged lines. Lintof and I were left mute in the center of this reconciliation. Finally. John's message came through, and we began to explore the merits of the 175 Honda.

I admired the man, not just his bravery, but also his showmanship, and, certainly, his incredibly advanced insanity.

By this time, a crowd had assembled outside the shop, expecting the worst, but eventuallv seeing the greatest show on earth. It began with Claus taking the midget, standing on the seat of a BMW. for a ride around the block. Then Georg did stunts on the practice track. Julius displayed his marksmanship. I did wheelies on a 441 Victor. The circus people were awed, they appreciated, clapped, even cheered. Thev knew class when they saw it.

The crowd: outlaws, locals, off-duty motorcycle cops, and shopping bag ladies from McDougall’s were amazed, but they weren't prepared to see the finale. Expertly, the Vultch drove a Hog ewer boards placed on the Strong Man's chest. Such a combined feat couldn't be topped, so we all adjourned to McDougall’s for an aftershow beer. Lintof was stunned, yet eventually he began to babble about a motorcycle act in his circus. I couldn’t see the point, because by now I knew that the bike came first and always.

That afternoon Lintof bought a 175 Honda in candy apple green. We fitted megaphones for a more impressive sound and adapted the wooden circled rims. Lintof was in time for the 8 p.m. show, we were all there as guests, and before going up the wire he made a speech under the Big Top praising us and our shop for all we had shown and done for him. Clearly, we. motorcycling, and technology had triumphed. It was an emotional moment, but the revised Lintof Theory prevailed, and I turned down an offer to become Lintofs protege. Lintof went on to become even more famous than he already was. I got my Rickman frame, still thinking of the Honda Four, and eventually headed north for Mosport Park secure in the knowledge that motorcycling was the greatest show on earth. Those were the days.