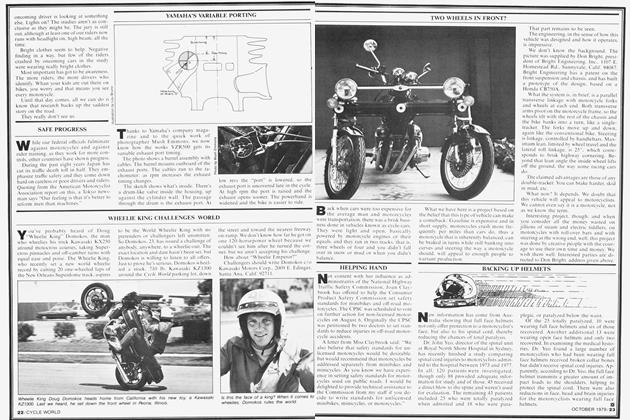

THEY HAVE EYES TO SEE

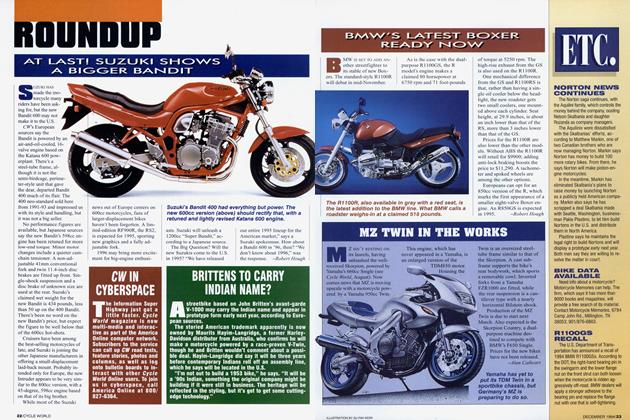

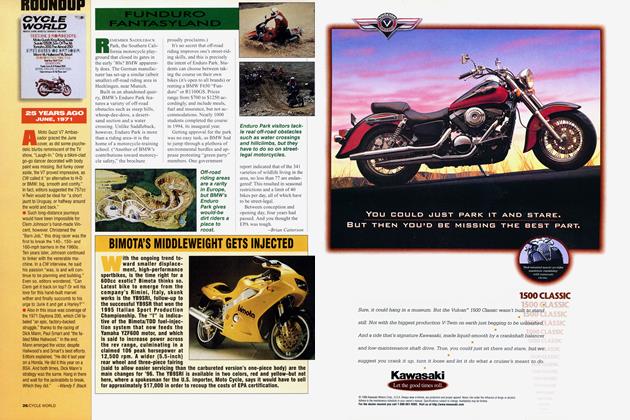

ROUNDUP

When the space researchers began planning the first close look at Venus, they ran into the sort of problem you don't even find in science fiction. One of the goals of the mission was to determine if there is life on that planet. They were fairly sure they wouldn't meet, say, a tribe of Amazons or flocks of small green creatures with antennas sprouting from their foreheads.

What they were completely unsure of was. what would life on another planet look like? And would they know it if they saw it?

If you don't know what to look for. how can you know if you see it?

They solved the problem, thev think, by using cameras that would record motion, and parking the cameras on the planet's surface. They might not know what it was scuttling around out there, they figured, but if it moved, that would be as close to a universal sign of life as they could expect. (Nothing moved, by the way, which doesn't prove anything. Mavbe next time.)

Exotic stuff'.

Moving closer to home, we've all seen those triek-the-eye puzzles, the ones that look like a blob or a series of shadows. That’s what you see. Then you read the answer and yes, once you know it’s Abraham Lincoln’s face, you can see the face.

What has this to do with motorcycles? More than most of us suspected.

The federally-funded Hurt study of motorcycle crashes with injury had one massive finding that will surprise nobody: The major factor evident in motorcycle accidents on public roads is the violation of the motorcycle's right-of-way by another vehicle.

Science proves w hat folklore knows. The bike is going down the street, under control, all systems legal and a car or truck turns into the bike’s path and wham! Another rider bites the dust or the car door.

It's a classic. Post-crash, the driver says “I didn’t see him.” and the rider says “He was looking right at me!”

Until now. it’s been a puzzle. We’re talking daylight, clear weather, sober people controlling both machines, on and on. Motorcycles are bigger than lampposts, small children, pedestrians, etc., and yet, “I didn't see him.” repeats itself time after time.

The cynics say E'unny, but they see cop motorcycles, except that the police get knocked down too. And sure, it’s difficult to expect anybody to say I saw him but I hit him anyway.

Even so, a puzzle.

Now though, as a followup to that first study. Dr. Harry Hurt and staff'have been interviewing the drivers. In depth. Not just age and circumstances, but experienee as well.

Didn't-See Drivers are. as Harry Hurt says, plain vanilla. Men and women, old and young, rich and poor and middle income, all walks of life.

Other than having turned into the path of a motorcycle hard enough to hurt, they have one other thing in common.

They have no motorcycle experience.

None.

Not one of the drivers surveyed so far ow ns or has ow ned a motorcycle. Nor have they ridden one. Nor do their wives or husbands or children or parents ride.

They are telling the truth.

They don't see us.

They don't see us because they aren't looking for us.

Presumably their physical equipment, the eyes and optical nerves and such register that directly in the center of the field of vision is a large shape, a fully dressed Gold Wing, say, but the brain, the internal systems that tell us to brake on red and control similar reflexes, don’t tell the driver not to nail that shape. They don’t know to look, just as the most attractive inhabitant of the planet Venus may have sashayed back and forth in front of our cameras, ready to sign the contract and become a Hollywood star, except that we didn't have the mental preparation to see her. Or it.

Interesting. Beyond that, and allowing that the Hurt survey is preliminary, we the motorcycling public have at least learned to see, so to speak, what the problem is.

What do we do now? For starters, if 50.8 percent of the crashes with injury are caused by violation of the bike’s right of way, if we can teach drivers to see, something like half the accidents won’t happen. We’ll never cure them all. of course. Drivers of cars and trucks also turn into the paths of cars and trucks. But if they saw us, they wouldn't hit us.

Some of the steps are obvious. Don't ride close behind a car. for instance, because we're even harder to see when the> oncoming driver is looking at something else. Lights on? The studies aren't as conclusive as they might be. The jury is still out, although at least one of our riders now runs with headlight on, high beam, all the time.

Bright clothes seem to help. Negative finding in a way, but tew oí the riders crashed by oncoming cars in the study were wearing really bright clothes.

Most important has got to be awareness. The more riders, the more drivers who identify. Whan your kids are out there on bikes, you worry and that means you see every motorcycle.

Until that day comes, all we can do is know that research backs up the saddest story on the road.

They really don't see us.