HONDA GL1000

CVCLE WORLD TEST

Honda Does a Wonderful Job Designing the Gold Wing For the People Who Buy It.

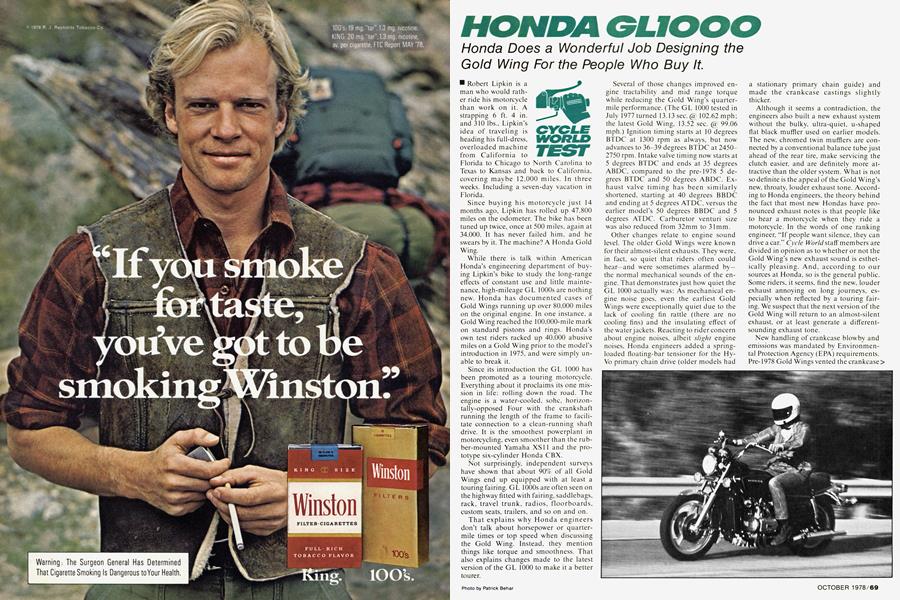

Robert Lipkin is a man who would rather ride his motorcycle than work on it. A strapping 6 ft. 4 in. and 310 lbs., Lipkin’s idea of traveling is heading his full-dress, overloaded machine from California to

Florida to Chicago to North Carolina to Texas to Kansas and back to California, covering maybe 12,000 miles. In three weeks. Including a seven-day vacation in Florida.

Since buying his motorcycle just 14 months ago, Lipkin has rolled up 47,800 miles on the odometer. The bike has been tuned up twice, once at 500 miles, again at 34.000. It has never failed him, and he swears by it. The machine? A Honda Gold Wing.

While there is talk within American Honda’s engineering department of buying Lipkin’s bike to study the long-range effects of constant use and little maintenance, high-mileage GL 1000s are nothing new. Honda has documented cases of Gold Wings running up over 80.000 miles on the original engine. In one instance, a Gold Wing reached the 100,000-mile mark on standard pistons and rings. Honda's own test riders racked up 40.000 abusive miles on a Gold Wing prior to the model’s introduction in 1975, and were simply unable to break it.

Since its introduction the GL 1000 has been promoted as a touring motorcycle. Everything about it proclaims its one mission in life: rolling down the road. The engine is a water-cooled, sohc, horizontally-opposed Four with the crankshaft running the length of the frame to facilitate connection to a clean-running shaft drive. It is the smoothest powerplant in motorcycling, even smoother than the rubber-mounted Yamaha XS11 and the prototype six-cylinder Honda CBX.

Not surprisingly, independent surveys have shown that about 90% of all Gold Wings end up equipped with at least a touring fairing. GL 1000s are often seen on the highway fitted with fairing, saddlebags, rack, travel trunk, radios, floorboards, custom seats, trailers, and so on and on.

That explains why Honda engineers don’t talk about horsepower or quartermile times or top speed when discussing the Gold Wing. Instead, they mention things like torque and smoothness. That also explains changes made to the latest version of the GL 1000 to make it a better tourer.

Several of those changes improved engine tractability and mid range torque while reducing the Gold Wing's quartermile performance. (The GL 1000 tested in July 1977 turned 13.13 sec. @ 102.62 mph; the latest Gold Wing. 13.52 sec. @ 99.06 mph.) Ignition timing starts at 10 degrees BTDC at 1300 rpm as always, but now advances to 36-39 degrees BTDC at 24502750 rpm. Intake valve timing now starts at 5 degrees BTDC and ends at 35 degrees ABDC, compared to the pre-1978 5 degrees BTDC and 50 degrees ABDC. Exhaust valve timing has been similarly shortened, starting at 40 degrees BBDC and ending at 5 degrees ATDC, versus the earlier model’s 50 degrees BBDC and 5 degrees ATDC. Carburetor venturi size was also reduced from 32mm to 31mm.

Other changes relate to engine sound level. The older Gold Wings were known for their almost-silent exhausts. They were, in fact, so quiet that riders often could hear—and were sometimes alarmed by— the normal mechanical sounds of the engine. That demonstrates just how quiet the GL 1000 actually was: As mechanical engine noise goes, even the earliest Gold Wings were exceptionally quiet due to the lack of cooling fin rattle (there are no cooling fins) and the insulating effect of the water jackets. Reacting to rider concern about engine noises, albeit slight engine noises, Honda engineers added a springloaded floating-bar tensioner for the HyVo primary chain drive (older models had a stationary primary chain guide) and made the crankcase castings slightly thicker.

Although it seems a contradiction, the engineers also built a new exhaust system without the bulky, ultra-quiet, u-shaped flat black muffler used on earlier models. The new, chromed twin mufflers are connected by a conventional balance tube just ahead of the rear tire, make servicing the clutch easier, and are definitely more attractive than the older system. What is not so definite is the appeal of the Gold Wing’s new, throaty, louder exhaust tone. According to Honda engineers, the theory behind the fact that most new Hondas have pronounced exhaust notes is that people like to hear a motorcycle when they ride a motorcycle. In the words of one ranking engineer, “If people want silence, they can drive a car.” Cycle World staff members are divided in opinion as to whether or not the Gold Wing’s new exhaust sound is esthetically pleasing. And, according to our sources at Honda, so is the general public. Some riders, it seems, find the new, louder exhaust annoying on long journeys, especially when reflected by a touring fairing. We suspect that the next version of the Gold Wing will return to an almost-silent exhaust, or at least generate a differentsounding exhaust tone.

New handling of crankcase blowby and emissions was mandated by Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) requirements. Pre-1978 Gold Wings vented the crankcase > breather tube into the atmosphere, while the latest model feeds into the airbox. (In the future, crankcase emissions will have to be routed into an oil-separator/catchtank, which probably will require emptying every 6000 miles or so.)

It used to be that if a Gold Wing was parked on the side stand, and if the rings on the left-hand pistons had rotated such that their end gaps were at the bottom of the horizontal cylinder wall, oil could seep into the combustion chambers. When the rider returned to the bike and started the engine, the accumulated oil could send a cloud of smoke from the exhaust pipes until the cylinders cleared out. To avoid

that, the engineers installed locating pins for the ring end gaps, preventing rotation. (Locating pins are routinely used for twostroke engine ring end gaps, so ring ends won’t snag in cylinder ports and break.)

In some respects, the Gold Wing’s engine requires less frequent servicing than other lOOOcc powerplants. Oil changes and valve adjustments are scheduled for every 7200 miles. Oil filter access is excellent, and Honda oil filters are usually less expensive than replaceable filter elements for other makes, due to the economies of production. (More Hondas using the same filter means lots of mass-produced filters at a relatively low price.) Conventional tap-

pets regulate valve lash, requiring only a wrench, screwdriver and feeler gauge for adjustment. Most 1000cc-and-larger machines sold today have double overhead camshafts and use a shim-and-bucket valve lash adjustment, which requires a set of shims and a special bucket depressor. Shim-and-bucket systems are known for requiring infrequent adjustment, but so are the Gold Wing’s tappets. Toothed rubber belts drive the cams, and do not require regular maintenance.

On the other hand, the GL 1000 uses contact breaker points, a disadvantage when compared to the inductive, pointless ignitions offered on some machines.

Features and maintenance considerations are important, but most important is how a touring machine goes down the road. The Gold Wing has plenty of power for real world use, even if this latest model is detuned in the interests of tractability. It’s not necessary to downshift on Interstate hills, and fifth-gear passing is just a matter of dialing on the throttle. For riders in a hurry, a stab into fourth gear will propel the GL past slower traffic like a peach pit shot out of an inner-tube slingshot.

The engine redlines at 8000 rpm, but shifting at 5000 rpm will leave normal stoplight or on-ramp traffic far behind. The GL 1000 loafs along at 3200 rpm at an indicated 55 mph, an indicated 65 mph requires 3800 rpm, and 5000 rpm gets about 90 mph on the speedometer. Only two things limit the length of time an unfaired Gold Wing will cruise at an indicated 90 or 100 mph: How long the rider can hang onto the new, semi-apehanger handlebars; and gas mileage. Ridden by heavy-handed staff members in mixed street/highway use, the Gold Wing usually delivered 32-35 miles per gallon of regular or low-lead gasoline. Kept close to the posted speed limits on the official Cycle World gas mileage test loop, the GL 1000 got 42 mpg. But ridden at unspeakable speeds down a deserted highway late one night, the Gold Wing sucked up petrol at a rate a little better than 25 mpg.

Four constant velocity (CV) Keihin carburetors feed the four cylinders. On machines with slide-throttle carbs, the twist grip is directly connected, via the throttle cable, to the carburetor slide. Twisting the grip raises the slide (admitting more air) and the attached needle (admitting more gas). But as in the case of other motorcycles with CV carbs, the Gold Wing’s twist grip pulls a cable connected (via a gang crank) to a butterfly throttle valve. When the butterfly throttle is opened, intake area is increased, but intake vacuum, not the throttle cable, raises the throttle slide and needle via a vacuum piston. It’s impossible to kill a CV-carbureted engine at low rpm by giving it too much throttle. And as a general rule—the exceptions being fitted to BMWs—CV carbs require lighter return springs than slide-throttle carburetors, which translates to less pressure demanded at the twist grip, which means less rider fatigue on long rides.

Unfortunately, CV carburetors often give the feeling that there isn’t quite a precise connection between the twist grip and the engine. Low speed carburetion has always been less than perfect on the Gold Wing, and the latest model is no different. Creeping along at a steady speed in the midst of a traffic jam is impossible in first gear and nearly impossible in second. Instead. the GL 1000 is always accelerating or decelerating, jerking to and fro, and no matter what the rider does with the twist grip, he can’t find a steady state. In part. that’s because the carburetors are very sensitive to slight changes in throttle opening. Then, too, the carburetion doesn’t always make the transition off idle perfectly, hesitating momentarily. At times it sounds as if the bike is firing on only three cylinders. How well the Wing responds off idle can be affected by spark plug heat range selection and also by ambient temperature. On hot days, the problem vanishes. But on cold days or chilly evenings, the stutter reappears. According to Honda, that’s partly because EPA emissions standards require a very lean low-speed mixture, which is too lean for proper off-idle response in cold, dense air. Again due to EPA requirements, the low-speed jetting cannot be altered. Other Gold Wings of similar vintage have displayed the same trait as our test bike, sometimes to a greater degree. Our GL1000, fitted with NGK D8EA plugs, was better than most. The rider gets used to it.

The rider also gets used to the certain amount of driveline snatch encountered in around-town riding. Unnoticed in higher gears or on the highway, accumulated transmission gear engagement dog and assorted driveline component tolerances combine with the sensitive throttle at slow speeds to produce a lurch if the twist grip is opened or closed suddenly. Being smooth with the throttle, instead of grabbing great handfuls or slamming it shut all at once, and with the clutch avoids or minimizes the snatch.

The Gold Wing’s five-speed transmission shifts smoothly and accurately with or without using the clutch. (Clutchless shifting isn’t recommended, but is one way to test a transmission.) Shifting from neutral into first gear at a stop often produces a large clunk, the sound of massive gears sliding into place, but engagement is positive. It’s doubtful anyone could break a Gold Wing transmission. The clutch is less immune to mistreatment. In normal use it’s fine, with a broad engagement point and moderate pull required at the handlebar lever. But suitability to street use isn’t the same as dragstrip suitability. Bringing a Gold Wing out of the gate at high rpm while slipping the clutch is guaranteed to fry the plates quickly. Anyone crazy enough to want to drag race a GL 1000 should bring several spare clutches.

In town or on the Interstate, it’s easy to overlook certain handling quirks of shaftdrive motorcycles. But if a foolhardy rider decides to take the Gold Wing out of its element and attempt to hustle down some twisty road, that’s another story. At sedate (i.e. legal) speeds, there is nowhere a GL 1000 cannot be taken safely. But at speed in the canyons, the bike is a handful. It is big and heavy, lacks ground clearance, and the rear end rises and falls under acceleration and deceleration, due to the action of the driveshaft pinion gear on the rear end crown wheel. The pinion gear tries to climb the crown wheel under acceleration, raising the motorcycle. Deceleration relaxes that tension and the rear end sinks.

Take, for example, a situation where a rider dives the Gold Wing hard into a blind, decreasing-radius curve, only to discover halfway around that he’s going too fast and that the bike is wallowing. More lean would tighten the line and maybe save the day, but all sorts of things drag on both sides of the GL, severely limiting lean angle. Slamming the throttle shut causes the rear end to drop, making things worse. There aren’t too many alternatives left: the best thing to do is to not sail into corners at full chat.

In one way, it’s too bad that the Gold Wing is a tourer and not a canyon racer: It certainly has the brakes. Along with the new Honda Comstar wheels, the GL1000 has been fitted with discs and calipers right off the 750F2 sports model. The new front brakes are lighter, feature thinner discs, look better and work great.

Gold Wing brakes gamed notice early this year not because the front brakes are excellent, but rather because the rear discbrake didn’t work well in the rain. Honda ended up recalling all 1975, 1976 and 1977 GLs, along with the first 5000 1978 Gold Wings. When a rider applies a disc brake in the wet, a film of water between the saturated pucks and wet discs acts as a lubricant, and nothing much happens. The rider applies more pressure at the brake pedal or lever, the water is squeezed out from between the pucks and disc, and the brake suddenly reacts normally to about twice the necessary lever pressure, locking the tire on wet pavement. The recall fix involved installing grooved pads made of different materials; the new pads recover their efficiency more rapidly when the brakes are applied in the rain. The front brake pads were already grooved on 1978 models, and, according to a Honda spokesman, the company did not receive complaints about front brake effectiveness under wet conditions. (Many riders avoid using the front brake in the rain, an unfortunate tendency. While care should be taken not to exceed available tire traction, the front brake should be used under all conditions, since normal weight transfer when braking makes the front brake more effective than the rear brake.) Ironically, the Gold Wing, like all motor vehicles, had to pass a National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) wet-braking test before being certified for sale in the United States. Goes to show what they know.

Even in a straight line on a highway, the Gold Wing has its own unique feel. The bike weighs 641 pounds with half a tank of fuel, an increase of 15 pounds over the last Gold Wing tested. The weight increase came from the thicker crankcase castings, the Comstar wheels, new higher handlebars, new (and excellent) dual horns, the new primary chain tensioner, redesigned center stand and a sidestand with a larger base, new step seat and a new> instrument housing—containing fuel gauge, new voltmeter and re-located temperature gauge—on top of the pseudo gas tank. On the other hand, some weight was lost in the exhaust system change and by eliminating the emergency kickstarter lever, which was formerly mounted under the right sidecover of the pseudo tank. (Gold Wings aren’t known for requiring kickstarting.)

However, the Gold Wing is unique among the heavier motorcycles sold today in that it carries its weight relatively low. The real 5-gallon gas tank, for example, is underneath the seat. (A fuel pump driven off the right cylinder head camshaft delivers gasoline up to the carburetors.) Flipping up the locking top cover (newly raised, padded and vinyl-covered this year) of the pseudo tank reveals the fuse box, tool-and-small-item storage tray (removable to allow air-cleaner access) and the gasoline filler cap. The plastic pseudo tank side covers conceal the radiator overflow tank and various electrical components, including a fused, 5-amp accessory jack for FM radio/tape player, CB, PA system, laser light show or other electronic gadget. All the really heavy stuif, like the crankshaft, transmission, clutch, cylinders, cylinder heads, 3.7 qts. of oil and other bits, is nestled down as close to the bottom frame rails as possible. The Gold Wing is stable at all speeds in still air, but the combination of low center of gravity and high handlebars makes the GL 1000 more susceptible to crosswinds than the 600-lb. Yamaha XS11, which weighs less but which has a higher center of gravity. In heavy winds, the Gold Wing feels like a sail boat, heeling over on a sharp tack. Remembering that most Gold Wings end up fitted with touring gear, including heavy high-mounted fairings and luggage racks with travel trunks, it could be that a fully-dressed GL 1000 would be more stable in sidewinds than a naked GL.

It’s also likely that the bike’s suspension is better suited for fully-loaded use than for carrying around single riders with no gear. One thing is certain: Carrying 140 pounds, the GL 1000 lacks suspension compliance and comfort. As is often the case, the bike’s forks and shocks react well to large, infrequent bumps in the road surface. But small, regular jolts like those produced by riding over concrete highway expansion joints don’t even make the suspension move. The rider’s shoulders are pummeled through the bars and his kidneys jabbed through the shocks.

According to specifications released by Honda early this year, the latest Gold Wing’s forks had 1 in. more travel than the forks on preceeding models. But when we disassembled the bike and mounted one fork on the shock test dyno, imagine our surprise: there was less than 0.1 in. increase in travel. A recheck of the specifications by Honda’s engineering department revealed an error and confirmed our findings. Compliance is somewhat improved, however, by the addition of a bevel cut on the bottom of the fork tube, which encourages oil to intervene between the tube and slider for less stiction. The specifications also list a 6mm-longer fork spring with a slightly softer initial compression rate and a change in the number and size of holes in the damping rod.

The shocks are changed as well. Now, two separate springs offer a cumulative compression rate of 135 pounds, versus the 100-pound constant rate springs on older models. The new secondary spring is heavier, while the initial spring has a softer rate. In theory, then, reaction to small bumps is improved while a suitable overall spring rate for heavy loads is retained.

Compared to earlier models, there is no doubt that the Gold Wing’s suspension action is better. But we know that it isn’t as good as the long-travel, very-compliant suspension on the Yamaha XS11 when both carry only a solo rider, and we suspect that the GL 1000 still wouldn’t match the Yamaha even if both were fully loaded.

The Gold Wing also comes up short when its seat is compared to that of the XS11. The.latest GL 1000 has a better seat than earlier models, but while padding seems to be improved, the shape isn’t quite right. The step-seat design looks nice and is popular with the public, but the raised rear section limits possible seating positions, a definite disadvantage for long stretches in the saddle.

The raised portion of the seat also bears uncomfortably against the tailbone area of some riders. Removing the passenger grab strap helps.

But in the case of handlebar grips, the GL1000 cannot be faulted. The bike has the best grips available on any street bike, soft and smooth enough to avoid irritating hands or wearing gloves during long rides, yet providing excellent grip and wear. The controls are also flawless, each being in the traditional place, easy to reach, and logical in function. The horn and starter buttons are twice the size of the buttons on most machines. The turn signal switch and high-beam/low-beam switches are also large and easy to find and work without looking while wearing heavy gloves.

The speedometer and tachometer too, are big and functional. Both have large, easy-to-read numbers and highly-visible needles. The speedometer is, as usual, optimistic, indicating 60 mph at an actual 56.2 mph. Instrument illumination is excellent: Reading the odometer or the resettable tripmeter is never difficult, even at night.

However, the fuel gauge, which along with the voltmeter and temperature gauge is set in the instrument pod on the top deck of the mock tank, is hopelessly pessimistic. The gauge needle points to reserve just 90 miles after filling the tank, when it’s normally possible to cover 135 miles or more before switching to reserve. It should be noted that a competent mechanic can recalibrate the fuel gauge to more accurately reflect reality.

One reality of motorcycling is that turn signal beepers, which are handy to remind short-minded riders to cancel the signals after a turn, can make a bike sound like a UFO at a signal. Honda has eliminated that irritation with a two-stage signal beeper. Below 40 mph, the beeper sends out subdued “clucks,” loud enough to be noticed by the motorcyclist, but not so loud as to have every motorist at an intersection looking skyward in anticipation of a close encounter. Above 40 mph, the beeper actually beeps with enough volume to be heard by the rider on the freeway.

Lighting is excellent. A new quartz iodine headlight throws a bright patch down the street, and is as good as or better than any other motorcycle headlight currently available. But as good as the light is relative to other machines, it still isn’t enough for high-speed travel down an unlit back road.

Huge dual-filament front turn signals double as running lights and make the Gold Wing easier to spot in traffic. The rear turn signals have been newly relocated to the taillight bracket to make mounting saddlebags easier.

Like the other changes made to the latest Gold Wing, the turn signal relocation fits the bike’s character and market perfectly. The GL 1000 is made for touring and used for touring. With a few additional changes, a better seat, more suspension travel and compliance, more gasoline capacity, and more precise low-speed carburetion—the Gold Wing could go on record as the most effective specialized ultralong-distance cruiser in existance. In the meantime, its capabilities are already welldefined and its reliability legendary. >

HONDA

GL1000

$3345

The new GL’s forks are essentially the same as last year’s, but relatively minor modifications have made a substantial improvement in fork action. The stanchion tube’s lower edge has a more gradual taper which promotes lubrication, and reduces wear while increasing compliance. The progressive spring has a softer initial rate for a more plush ride, but static seal friction is still far too high. A set of aftermarket seals would be advantageous here.

New shocks and springs support the Wing’s aft end. Rebound damping of the FVQ units is down from prior models, a change which makes the bike a bit less stable at speed, especially in fast, undulating sweepers. On the plus side, the new dual-spring setup firms up the rear nicely. Lightweight solo riders may find the springs a bit harsh, but touring riders with a passenger or baggage will appreciate the increase in effective rate. EB

Tests performed at Number 1 Products

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontYou Can't Take the Harley Out of the Boy

October 1978 By Allan Girdler -

Departments

DepartmentsBook News

October 1978 By A.G., Chuck Johnston, Michael M. Griffin -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1978 -

Departments

DepartmentsRoundup

October 1978 -

Short Strokes

October 1978 By Tim Barela -

Technical

TechnicalYamaha It250/400 Steering Fix

October 1978 By Len Vucci