THE BETTER WAYS OF JOE BOLGER

He Who Does Things Differently Usually Does Them On His Own

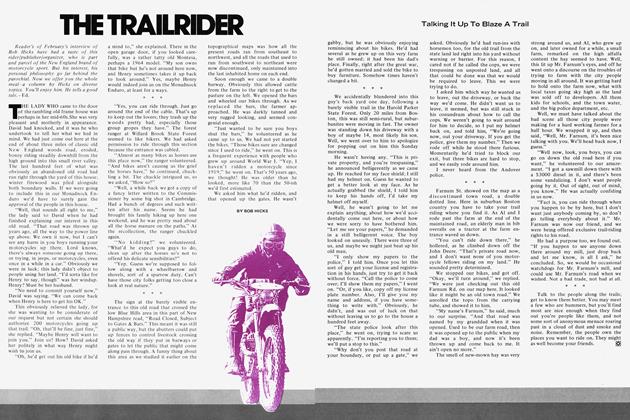

Bob Hicks

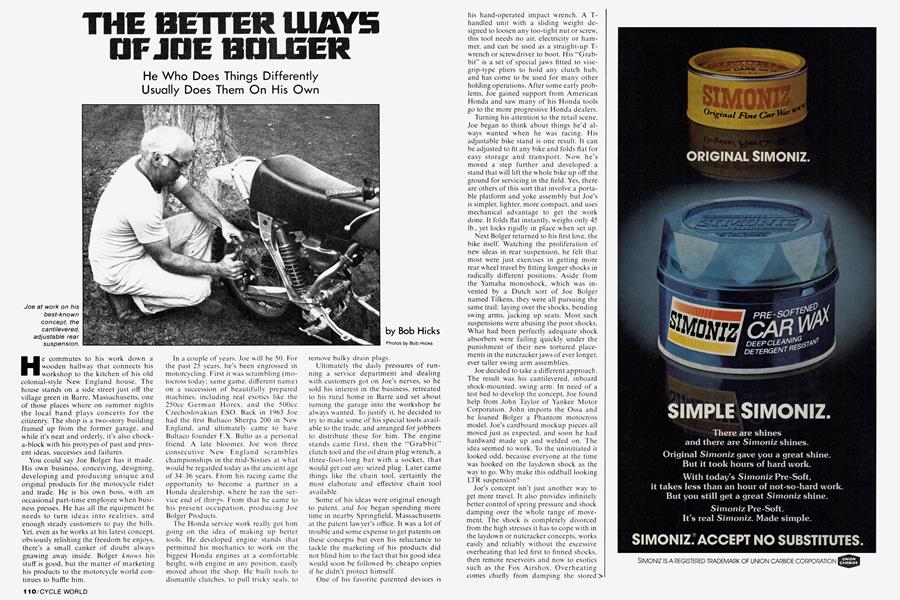

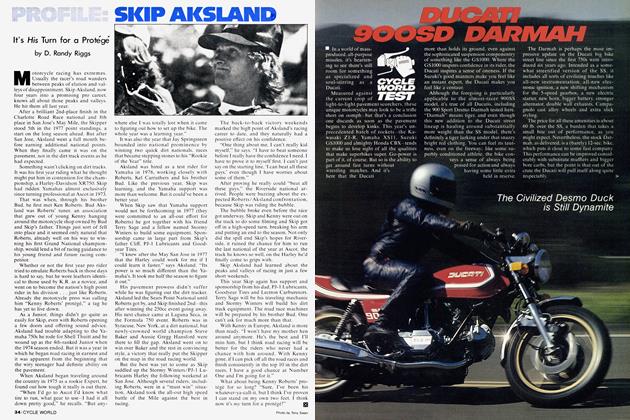

He commutes to his work down a wooden hallway that connects his workshop to the kitchen of his old colonial-style New England house. The house stands on a side street just off the village green in Barre, Massachusetts, one of those places where on summer nights the local band plays concerts for the citizenry. The shop is a two-story building framed up from the former garage, and while it's neat and orderly. it's also chocka-block with his protypes of past and present ideas, successes and failures.

You could say Joe Bolger has it made. His own business, conceiving, designing, developing and producing unique and original products for the motocycle rider and trade. He is his own boss, with an occasional part-time employee when business presses. He has all the equipment he needs to turn ideas into realities, and enough steady customers to pay the bills. Yet, even as he works at his latest concept, obviously relishing the freedom he enjoys, there’s a small canker of doubt always gnawing away inside. Bolger knows his stuff is good, but the matter of marketing his products to the motorcycle world continues to baffle him.

In a couple of years, Joe will be 50. For the past 25 years, he’s been engrossed in motorcycling. First it was scrambling (motocross today; same game, different name) on a succession of beautifully prepared machines, including real exotics like the 250cc German Horex, and the 500cc Czechoslovakian ESO. Back in 1963 Joe had the first Bultaco Sherpa 200 in New England, and ultimately came to have Bultaco founder F.X. Bulto as a personal friend. A late bloomer. Joe won three consecutive New England scrambles championships in the mid-Sixties at what would be regarded today as the ancient age of 34-36 years. From his racing came the opportunity to become a partner in a Honda dealership, where he ran the service end of things. From that he came to his present occupation, producing Joe Bolger Products.

The Honda service work really got him going on the idea of making up better tools. He developed engine stands that permitted his mechanics to work on the biggest Honda engines at a comfortable height, with engine in any position, easily moved about the shop. He built tools to dismantle clutches, to pull tricky seals, to remove balky drain plugs.

Ultimately the daily pressures of running a service department and dealing with customers got on Joe’s nerves, so he sold his interest in the business, retreated to his rural home in Barre and set about turning the garage into the workshop he always wanted. To justify it, he decided to try to make some of his special tools available to the trade, and arranged for jobbers to distribute these for him. The engine stands came first, then the “Grabbit” clutch tool and the oil drain plug w rench, a three-foot-long bar with a socket, that would get out any seized plug. Later came things like the chain tool, certainly the most elaborate and effective chain tool available.

Some of his ideas were original enough to patent, and Joe began spending more time in nearby Springfield. Massachusetts at the patent lawyer's office. It was a lot of trouble and some expense to get patents on these concepts but even his reluctance to tackle the marketing of his products did not blind him to the fact that his good idea would soon be followed by cheapo copies if he didn't protect himself.

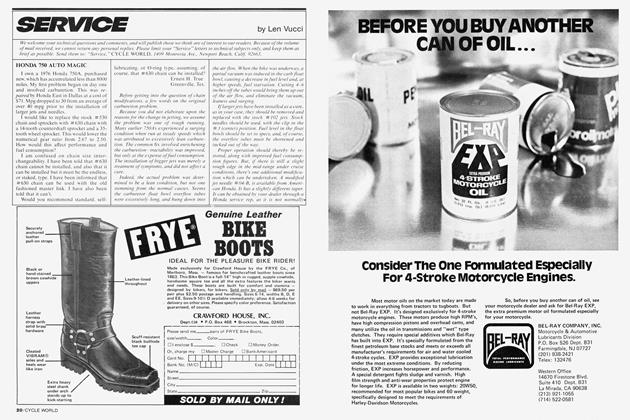

One of his favorite patented devices is his hand-operated impact wrench. A Thandled unit with a sliding weight designed to loosen any too-tight nut or screw', this tool needs no air, electricity or hammer, and can be used as a straight-up Twrench or screwdriver to boot. His “Grabbit” is a set of special jaws fitted to visegrip-type pliers to hold any clutch hub, and has come to be used for many other holding operations. After some early problems, Joe gained support from American Honda and saw many of his Honda tools go to the more progressive Honda dealers.

Turning his attention to the retail scene, Joe began to think about things he’d always wanted when he was racing. His adjustable bike stand is one result. It can be adjusted to fit any bike and folds flat for easy storage and transport. Now he’s moved a step further and developed a stand that will lift the whole bike up off the ground for servicing in the field. Yes, there are others of this sort that involve a portable platform and yoke assembly but Joe’s is simpler, lighter, more compact, and uses mechanical advantage to get the work done. It folds flat instantly, weighs only 45 lb., yet locks rigidly in place when set up.

Next Bolger returned to his first love, the bike itself. Watching the proliferation of new ideas in rear suspension, he felt that most were just exercises in getting more rear w'heel travel by fitting longer shocks in radically different positions. Aside from the Yamaha monoshock, which w'as invented by a Dutch sort of Joe Bolger named Tilkens, they were all pursuing the same trail: laying over the shocks, bending swing arms, jacking up seats. Most such suspensions were abusing the poor shocks. What had been perfectly adequate shock absorbers were failing quickly under the punishment of their new tortured placements in the nutcracker jaws of ever longer, ever taller swing arm assemblies.

Joe decided to take a different approach. The result w'as his cantilevered, inboard shock-mounted, swing arm. In need of a test bed to develop the concept. Joe found help from John Taylor of Yankee Motor Corporation. John imports the Ossa and he loaned Bolger a Phantom motocross model. Joe’s cardboard mockup pieces all moved just as expected, and soon he had hardward made up and welded on. The idea seemed to work. To the uninitiated it looked odd, because everyone at the time was hooked on the laydown shock as the way to go. Why make this oddball looking LTR suspension?

Joe’s concept isn’t just another w-ay to get more travel. It also provides infinitely better control of spring pressure and shock damping over the whole range of movement. The shock is completely divorced from the high stresses it has to cope w'ith in the laydown or nutcracker concepts, works easily and reliably without the excessive overheating that led first to finned shocks, then remote reservoirs and now to exotics such as the Fox Airshox. Overheating comes chiefly from damping the stored > spring energy on rebound. With 200-in./ lb. springs this can get up to 1000 in./lb. of pressure to contol on release. Bolger’s setup requires 100 in./lb. springs typically, half that needed in conventional LTR suspensions. Half the stored energy, half the energy to be damped, half the heat build up. Joe’s design lets the leverage do the work. And it permits easy and instant adjustment of spring rate and damping in the held, merely by shifting the pivot pins and thus changing the relationship of the levers and how they act upon each other as they transfer the swing arm loading to the shock unit.

continued from page 111

Does it work? Joe had to find out in the held. He got together with a rider he respected, Joe Collins, 1976 New England Open Class champion. Collins, 28. was an experienced rider who could tell what was happening under him. The test was simple. They took Collins’ Maico and Bolger’s Ossa to the local track. Collins started on his Maico and after some 20 minutes got his lap times down to a steady 2 minutes and 13 seconds. Then he got oh'the 400cc championship winning bike, and onto the year-old 250cc test hack. His hrst laps were at 2 min. 15 sec. Within 10 laps, he was down to 2 min. and 10 sec., this on a yearold bike unfamiliar to him. Collins was impressed.

What was happening? The Bolger suspension was keeping the wheel on the ground more. Its concept is such that at smaller displacements of the wheel, it is sensitive to all variations in terrain. As impacts displace it further, the action progressively resists. Collins found he was able to go far deeper into turns. The rear wheel would hang onto the ground so well he could still get slowed as much as the turn required while delaying braking. Another advantage the unique concept demonstrated was its ability to keep the wheel on line over diagonal ruts, ditches, jumps. The impact of the leading edge of the angular ditch would not lift the wheel off the ground and shove the bike off at an angle. Looking at tire marks over a series of small parallel ridges hit at an angle showed the Bolger-equipped bike to have left a far more complete track on the ground than did the conventionally suspended bike. The wheel was staying on the ground.

So Joe Bolger’s suspension seems to provide something that plain long travel does not. With things developed to this extent, Joe began to look into prospects for getting the unit marketed. As an aftermarket suspension it w'as awkward, for it required cutting away part of the stock frame and carefully welding on the Bolger chassis parts. It wasn’t a bolt-on so the average rider wouldn’t be a likely customer. Taylor arranged to provide service.

continued on page 114

SOME BETTER IDEAS BY BOLGER

If an Ossa prospect w ished one fitted, the new bikes would go directly to Taylor’s facility where the Bolger suspension w'ould be installed. There were two main limitations on this marketing approach. One, nobody had been out there racing this suspension and winning and thus developing a name. Tw'o. the available hardware was tailored to Ossa, not one of the more widely used ofif-roaders, at least in motocross. So once again, that obstacle arose: How to sell the idea, how' to make it pay enough to earn its keep and reward its creator.

An effort was made to interest Ossa in fitting the suspension as factory equipment, but that firm displayed reluctance to adopt it in place of its own design department’s ideas. Inquiries to several of the major Japanese firms were politely received but not acted upon. So here was this obscure tinkerer/engineer/in ven tor/designer with a product incorporating original ideas and demonstrable advantages, face to face with a stone wall w hen it came to marketing it.

Joe goes on anyway. Even as he was trying to get his suspension into use, he was coming up with his own solution to the chain travel variation that the long travel suspensions were creating. Standard de-> sign concept in dealing with this has been ever more complex chain tensioning devices. Yet even Yamaha watched its national star Bob Hannah fail to finish in 1977 because of chain fly-ofif problems. More recently, the trend is to moving the countershaft sprocket and swing arm pivot into closest possible proximity. While this reduces the chain variation, it lengthens the swing arm and thus requires heavier construction to resist bending. Bolger characteristically took an original approach. He developed a swing arm unit that eliminated all chain tension variation, again by use of simple lever action.

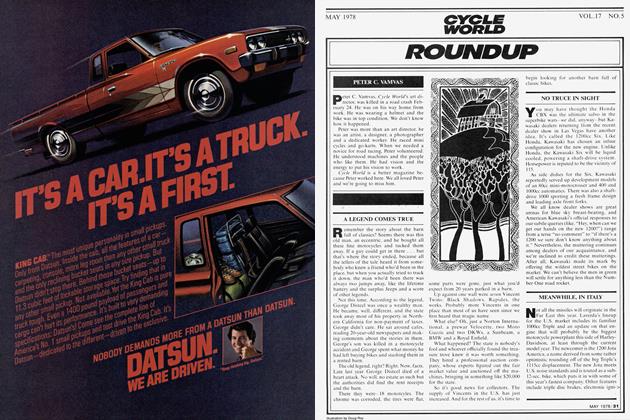

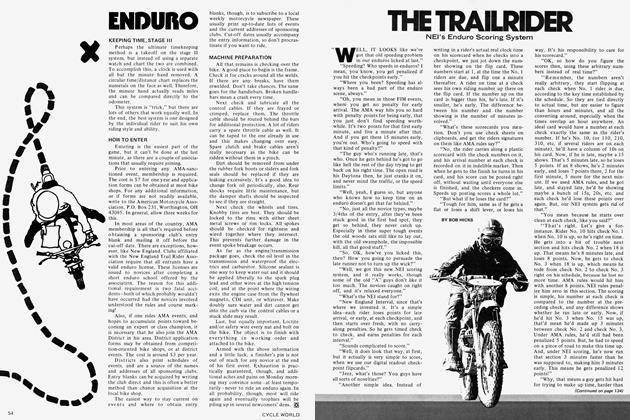

HOW BOLGER’S SUSPENSION WORKS

1) Full extension. Angle A is at maximum leverage but Angle B is at its softest, so a slight upward deflection of the wheel is immediately absorbed by the shock/spring. In this position the leverage is 2:1, so spring resistance is at its lowest.

2) Compression under way. Angle A approaches a right angle, losing leverage, while Angle B approaches a right angle from the other direction, gaining leverage. Top location of shock, in X or Y position, provides initial setting, to allow for rider weight. Tuning for track conditions is done by setting rear link S in the choice of holes at the top and bottom mounts.

3) Compression continues. Angle A is now past a right angle and is losing leverage, and Angle B is almost at a right angle, still gaining. The result is an increase in resistance, i.e. an effective gain in spring rate.

4) Near full compression. Angle A is still losing leverage and Angle B is at a right angle, its stiftest. The 2:1 ratio approximately halves the spring tension required to handle maximum impact at full compression, while the relatively light rate works with small loads. Loading on the shock is almost directly in line with the axis of the piston and side loadings are small. This is opposite to the laydown design, where the shock loses mechanical advantage and side loads increase during the compression stroke.

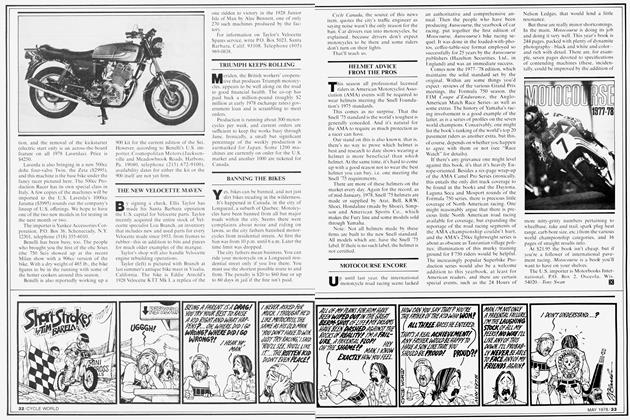

Joe’s swing arm is conventional until it gets back to the rear axle mounting. There’s a short, vertical arm pivoting where the axle usually goes. The axle in turn fits at the top of the vertical link. The bottom of the link carries one end of a horizontal arm. a long one, which attaches to the frame behind the swing arm pivot.

The secret is the geometry. As the rear wheel swings through its arc about the swing arm pivot, that is, up and down, the movement and the linkage cause the vertical arm to also move in an arc, back and forth. On compression the swing arm goes up. moving closer to the pivot and thus creating slack in the chain. But the vertical arm moves the axle mounting point away from the pivot, exactly the same distance that wheel travel moves the axle closer to the pivot.

In short, there is no variation in chain tension. None. Where chain tensioners usually fail is in not being able to keep up w ith the w ild gyrations of the slack chain as the wheel leaps up and down and the rider turns power on and oft'.

Bolger’s design doesn't allow' slack so there is no flailing about. The chain is alw ays tensioned as set. Of course in a long moto or enduro, chain wear might create some slack. In motocross, simple betweenmoto adjustment can return tension to full tight. In enduro use a similar adjustment can be made at a gas stop or anywhere it seems needed. The controlling factor is the chain strength, not the suspension created variation in slack.

Simple concept, one that demonstrably works. It’s patented, because it is original. Now, who wants to use it? Again that baffling marketing problem. Who believes a lone inventor in a country town can build a better mousetrap than a computerized multi-disciplined engineering department in a major manufacturing firm? Who indeed?

Baffled as he is by this hurdle to success, Joe Bolger goes on dreaming up and building better ways to ride and service motorcycles. His tools sell well enough to support him. but really need to be sold like Snap-On does, through franchised local traveling dealers. His suspension breakthrough still sits in the doldrums. Several top New England enduro riders use it on their Ossas. One is George Peck, w inner of a 1977 championship. George remarks that his Ossa Super Pioneer isn’t fast enough, but the suspension enables him to travel quickly in the tightest, roughest going. A few' motocrossers have Ossa Phantoms with the Bolger suspension, but Ossa isn’t supporting any motocross rider nationally and anyway, the factory isn’t too enthused. Joe has some interest in his chain tension control swing arm from a major manufacturer, but that’s still in a very preliminary stage.

It’s a good thing Joe enjoys his work,

and finds the constant challenge of developing that better way those Ford Motor Company ads talk about. Unlike Ford, Joe Bolger’s better ways have yet to reward him financially. Maybe it’s just not in the cards in modern America for one man working alone in a shop attached to an old house in a country town to make it in a big way in the modern motorcycle world. Perhaps the only reward is in the doing. If that’s all there is, Joe Bolger isn’t complaining. Just as long as he can keep on working in his shop on w hatever arouses his interest.