INSIDE HAWKS

Honda's new Hawks begin with an old idea: the vertical twin, cooled by air and driving the wheel via a chain. The news is that Honda engineers have taken this established idea and developed it into an engine that's not only new but will have a useful life through the coming years of struggle and compliance with the demands of buyers and various government agencies.

The Hawk engine is severely over square, that is, a large bore and short stroke. Honda uses dimensions of 70.5 x 50.6 mm, compared with 65 x 60 mm for the Suzuki GS400 and 69 x 52.4 mm for the Yamaha XS400. The short stroke gives less torque at low engine speeds but allows higher engine speeds, so the engine can have more peak power.

The cylinder head has a single-overhead camshaft located directly above the bore centers, activating the valves with short rocker arms. There is one large exhaust valve and two smaller intake valves, chosen because two small valves will flow more air with less total bulk.

This isn’t done for power. The combustion chamber is of the pent roof type. The piston crown is slightly domed and the spark plug is offset. The five basic shapes within the chamber itself have been designed so as to swirl the mixture and give even combustion, to reduce knock and make combustion as complete as possible. The Hawk engines can use no-lead fuel with a relatively high compression ratio making them more efficient, and the engine will conform to the coming emissions regulations without add-on devices or poor running. With this comes more than adequate performance and a claimed power of 40 bhp from 395 cc. Not too many years ago 100 bhp/1000 cc was something only achieved by racing engines.

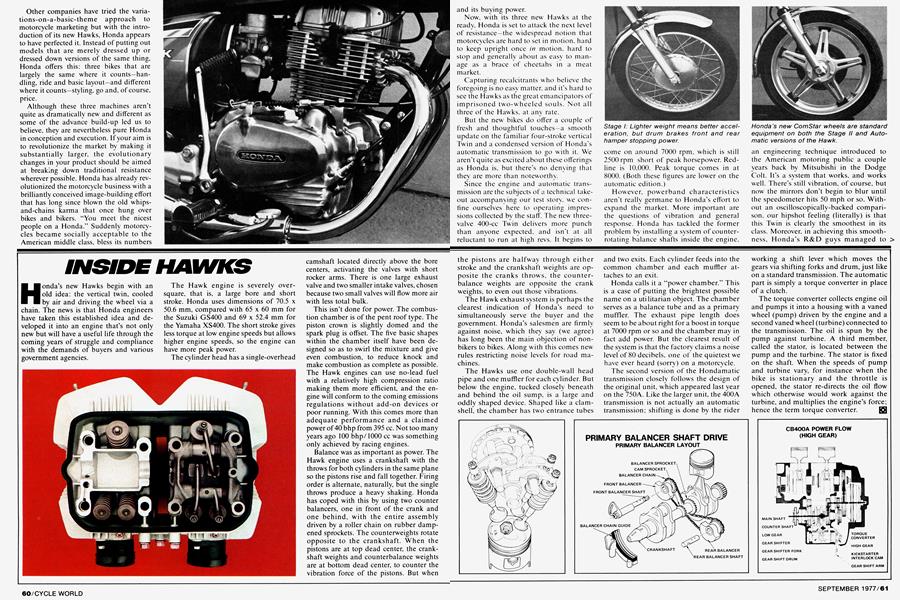

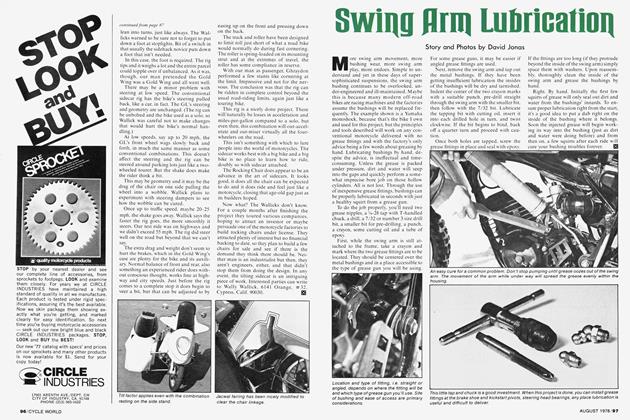

Balance was as important as power. The Hawk engine uses a crankshaft with the throws for both cylinders in the same plane so the pistons rise and fall together. Firing order is alternate, naturally, but the single throws produce a heavy shaking. Honda has coped with this by using two counter balancers, one in front of the crank and one behind, with the entire assembly driven by a roller chain on rubber dampened sprockets. The counterweights rotate opposite to the crankshaft. When the pistons are at top dead center, the crankshaft weights and counterbalance weights are at bottom dead center, to counter the vibration force of the pistons. But when the pistons are halfway through either stroke and the crankshaft weights are opposite the cranks throws, the counterbalance weights are opposite the crank weights, to even out those vibrations.

The Hawk exhaust system is perhaps the clearest indication of Honda’s need to simultaneously serve the buyer and the government. Honda’s salesmen are firmly against noise, which they say (we agree) has long been the main objection of nonbikers to bikes. Along with this comes new rules restricting noise levels for road machines.

The Hawks use one double-wall head pipe and one muffler for each cylinder. But below the engine, tucked closely beneath and behind the oil sump, is a large and oddly shaped device. Shaped like a clamshell, the chamber has two entrance tubes and two exits. Each cylinder feeds into the common chamber and each muffler attaches to an exit.

Honda calls it a “power chamber.” This is a case of putting the brightest possible name on a utilitarian object. The chamber serves as a balance tube and as a primary muffler. The exhaust pipe length does seem to be about right for a boost in torque at 7000 rpm or so and the chamber may in fact add power. But the clearest result of the system is that the factory claims a noise level of 80 decibels, one of the quietest we have ever heard (sorry) on a motorcycle.

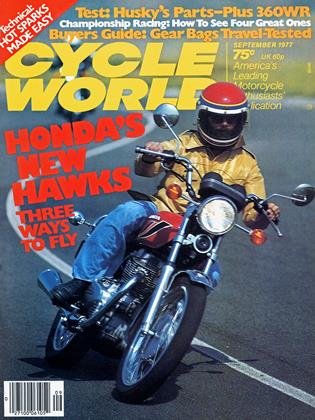

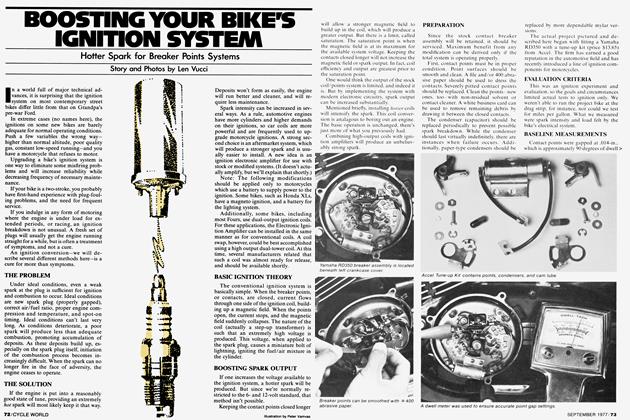

The second version of the Hondamatic transmission closely follows the design of the original unit, which appeared last year on the 750A. Like the larger unit, the 400A transmission is not actually an automatic transmission; shifting is done by the rider working a shift lever which moves the gears via shifting forks and drum, just like on a standard transmission. The automatic part is simply a torque converter in place of a clutch.

The torque converter collects engine oil and pumps it into a housing with a vaned wheel (pump) driven by the engine and a second vaned wheel (turbine) connected to the transmission. The oil is spun by the pump against turbine. A third member, called the stator, is located between the pump and the turbine. The stator is fixed on the shaft. When the speeds of pump and turbine vary, for instance when the bike is stationary and the throttle is opened, the stator re-directs the oil flow which otherwise would work against the turbine, and multiplies the engine’s force; hence the term torque converter.

PRIMARY BALANCER SHAFT DRIVE PRIMARY BALANCER LAYOUT

CB400A POWER FLOW (HIGH GEAR)