CHAMPION SPARK PLUG 200

LAGUNA SECA

Skip Aksland Spoils Steve Baker’s Triumphal Homecoming

Tony Swan

In motorcycle racing the surest indication of the onset of fame is when people recognize you even though your leathers are still locked up in the van. It’s one thing for someone to know your number, or read the name on your uniform and connect it with the one they’ve been hearing and/or reading during the course of the season. It’s quite another thing to have someone make the same connection simply by seeing your face.

For Steve Baker, the transition from ordinary recognition to dawn of fame has taken only a single season. When he headed off to the European pavement racing wars after winning Daytona last spring, he was certainly well known to his contemporaries. But the name Baker was still essentially faceless in the minds of many U.S. race followers, and in Europe it was pronounced something like Steve Who?

It didn’t take Baker long to shed the cloak of invisibility. Steve and his Yamaha became all too familiar to other riders in the world Formula 750 title circus. By the time he got back for a race on U.S. pavement again, at Laguna Seca Raceway last fall, he’d already become the first American to win a world championship, having wrapped it up several weeks earlier. And as Baker wandered through the Laguna Seca paddock during his spare moments, clad with reasonable anonymity in the bottom half of his red and white leathers and a Gauloises T-shirt, it was, “Hey, champ, howzit goin’?” and “Hey Steve, sign my program, willya?” and “Blow their doors off, champ!” It seemed impossible for Baker to take more than a half-dozen steps without having to stop for some wellwisher. The newness of this treatment still showed in Baker’s polite self-consciousness in his dealings with his public, and he modestly discounted the tide of Steve Baker fans.

“I think it’s just because there are so many people from Bellingham (Washington. Baker’s hometown) down here for the race,” he said.

Dramatically increased visibility wasn’t the only lesson of the Laguna meeting for Baker, however, and the second one was much more significant than the realization of celebrity status. It’s an old song and goes like this: Lose when you're only a contender, and people talk about your next shot at the title. Lose when you’re on top and the whispers begin to follow you through the pits.

However, the defeat, administered by Skip Aksland. was far from disastrous and more a matter of Baker getting caught napping after a long summer of having things pretty much his own way. And the impending ambush was an unlikely one, involving not only the 20-year-old Aksland but a big Australian riding—are you ready?—a Kawasaki. Baker can be forgiven for failing to appreciate the intensity of the storm gathering around him, and if it took something of the triumph out of his homecoming. he seemed to have profited by it, showing in the second half of the two-heat feature program that he is (a) resilient and (b) still the master.

From a spectators’ point of view, Aksland’s antics, confined with some dynamite shows in the supporting events, saved the Champion Spark Plug 200 weekend from being a disappointment. The idea of an international event with an American world championship contender at its center certainly seemed like a good one when promoters Gavin Trippe and Bruce Cox put it together, but long before the actual date the title was decided. As a consequence the number of European riders of star stature was limited indeed, and the few who did make the program—notably Frenchman Christian Sarron and Hubert Rigal, from Monte Carlo—were hampered by their unfamiliarity with the track and the American Motorcyclist Association qualifying procedure, which was totally new to them. Another conspicuous absentee was Kenny Roberts, who was off campaigning his flat track Yamaha—fruitlessly, as it turned out—in an AMA Camel Pro Series event at Syracuse, New York.

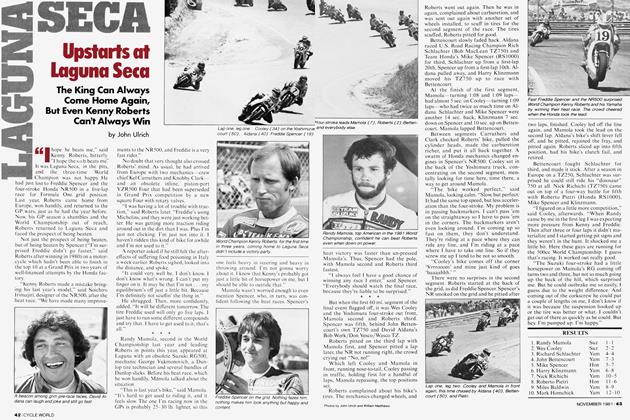

Few of the foreign riders, who are accustomed to qualifying sessions that allow them a large number of timed laps, fared well with the AMA method of one warmup lap followed by one let-it-all-hang-out timed circuit to determine starting position. Of the European Lormula 750 regulars, Sarron did the best, snorting around Laguna's 1.9 miles in 1:12.582 (about 94 mph), which was almost a second and a half off the pole time. With one surprising exception, the front row belonged to men more familiar with the one-hot-lap qualifying program: Gene Romero, who was about as dialed into that system as anyone present (with the possible exception of Gary Nixon), wound up with the pole in 1:11.012, which was .027 sec. better than Baker and .251 quicker than Aksland.

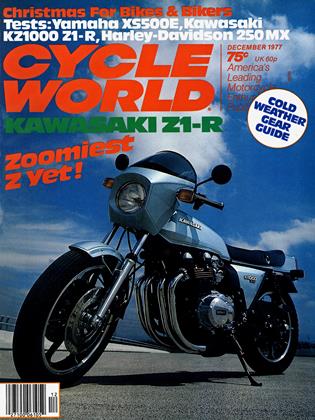

The surprising front row intruder was Australian Gregg Hansford, who qualified in 1:12.515 on the only Kawasaki in the field. However. Hansford didn’t exactly materialize out of the blue; the Kaw was the same one he’d ridden to 4th place at Daytona. Erom Hansford down to 11th qualifier Jimmy Morales, a Mexican whose approach to the business of getting around a race track seems to be very much in the tradition of his late countrymen Ricardo and Pedro Rodriguez, it was an all-American show with Dave Aldana, Ron Pierce and Nixon rounding out the second row, and Steve McLaughlin and Mike Baldwin leading off the third.

There followed a series of heat races— for the 250cc lightweights, superbikes and sidehacks—that set the tenor of the competition for the entire weekend, which is to say hot. Hansford served notice that something unusual was afoot by sneaking his 250cc Kawasaki home ahead of the mob of Yamahas ranged against him, one of them ridden by Nixon, and Baldwin put on an excellent show in the second heat to beat Randy Mamola, one of the most promising youngsters (17 years old) in pavement racing.

Thanks to Craig Vetter’s last-minute sponsorship production of the superbike segment of the show, there was a first-rate field on hand with a variety of different manufacturers represented. McLaughlin, making his first outing on the brand new and very potent Yoshimura Suzuki GS750, established himself as the man to beat by coming home ahead of Reg Pridmore's Kawasaki and Cook Neilson’s Ducati in the heat race, although there wasn't enough of an interval between 1st and 3rd to say Rumpelstiltskin.

About the only area of the weekend’s competition that was actually dominated by Europeans was the sidecars. British ace George O'Dell was out of the action early following a getoff in Turn 6, Laguna’s famous downhill Corkscrew, during practice on Lriday. O'Dell’s passenger. Cliff Howard, got out of the tumble with as-> sorted lumps and scrapes, but O’Dell wound up with a broken left leg when the Yamaha-powered rig flipped over.

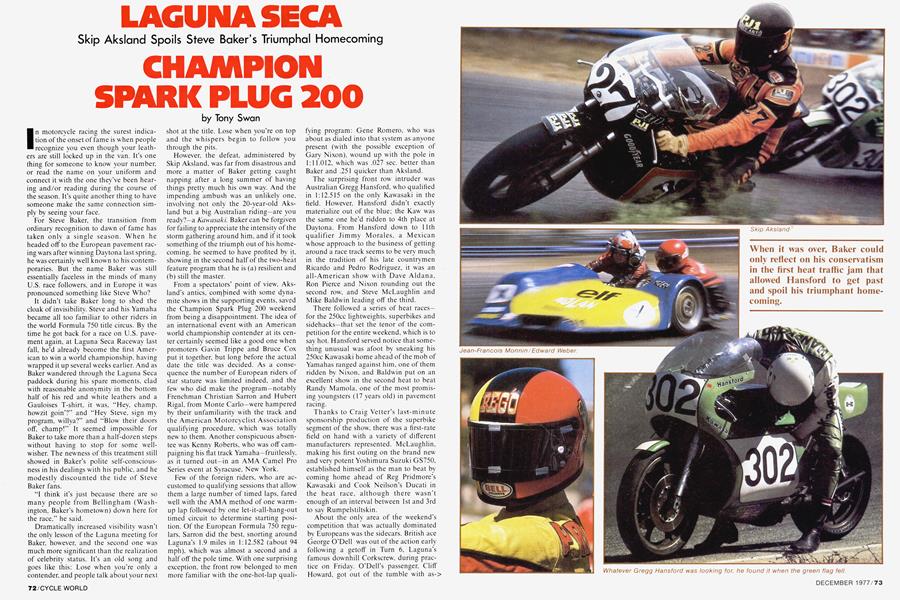

When it was over, Baker could only reflect on his conservatism in the first heat traffic jam that allowed Hansford to get past and spoil his triumphant home coming.

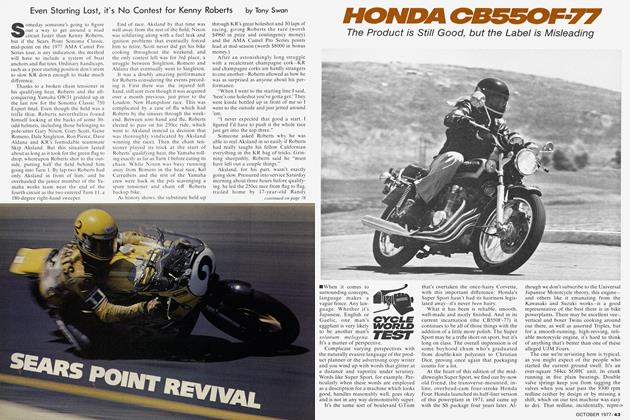

Steve McLaughlin will go to almost any length to win, and gets away with antics that would have other men chewing the hay bales.

RESULTS• CHAMPION SPARK PLUG 200. LAGUNA SECA RACEWAY

Although there were plenty of entries from both sides of the great waters, O'Dell’s crash made it pretty much a twohack showdown between Jean-Francois Monnin/Edward Weber, from Switzerland, and former world champion Rolf Steinhausen, with passenger Wolfgang Kalauch, both from Berlin. The Yamahapowered Monnin/Weber rig, which featured such refinements as center hub steering for both the front wheel and hack wheel, was the quickest of the lot. One of the benefits of this unusual steering setup was that passenger Weber’s only duty was to create as little wind resistance as possible. In contrast to the acrobatics of the monkeys on the other hacks, the only reason Weber seemed to be on the rig was to satisfy the rules. Some observers thought the machine impure.

If some of Saturday’s proceedings seemed to portend a dynamite show for the weekend, the 250cc final removed any remaining doubt, as Hansford and Nixon locked up in one of those duels that give Laguna watchers stiff necks. It was one of those wild Gary Nixon affairs that oldtime bikers will be pouring out years from now like fine old wine. In this one, Hansford was the Other Guy, taking the holeshot, trailing at the end of the first lap, then sneaking out front again to lead through the next three, although Nixon was shadowing him like a bill collector. Lap five and Nixon found a way past the Kawasaki, only to get into the dirt negotiating the Corkscrew and fall to 4th place behind Dave Emde and Mamola in the process.

This allowed Hansford to breathe easy for all of three laps. The rest of the way distinction between 2nd and 1st places got to be a very subtle one. All this skirmishing carried Hansford and Nixon well away from the rest of the field, which was led by Emde, who was stalked but never quite caught by Mamola. Mamola, in turn, was running by himself in front of another great struggle, this one between Baldwin and John Long.

continued on page 86

The Nixon-Hansford issue was resolved near the end of lap 18 (of 20) when Nixon, leading at the time, got into Turn 9 a trifle too hot and spent precious milliseconds wrestling the Yamaha, to see who would remain on top while Hansford got away. Nixon was getting enough horsepower from the Erv Kanemoto-tuned Yamaha to reel the Australian in again, but he was about a half-a-length short at the flag. Deprived of victory. Nixon had to settle for a little fun instead, and he reached out to give Hansford a sharp swat on the bum just as the two flashed under the starter’s bridge.

Emde. by that time some 10 seconds back, motored home securely in 3rd place, with Mamola a short way behind. Then it was time to tune into the Baldwin-Long show again, as the two rushed into Turn 9 only inches apart. There it became a question of line. Long diving to the inside, Baldwin to the outside. The key to the outcome lay with a lapped bike that both were overtaking, and onee committed to the inside. Long found himself balked, allowing Baldwin to win the drag race to the flag.

Aksland started Sunday’s proceedings bv showing a cool nerve when his bike went into a hairy high speed wobble after a steering damper went away. Then, with the defective damper replaced, went out again to turn the weekend’s hottest practice laps. With consecutive rounds of 1:10.56, 1:10.15 and 1:10.06. all faster than the course record of 1:10.6 (about 97 mph), Aksland’s consumer model Yamaha looked to be the hot setup.

The tire war also looked to be interesting. with three different manufacturers represented in the top five starting positions. Romero. Aksland and Hansford were all riding Goodyears. Baker was on Dunlops and Sarron on Michelins. No one seemed to be getting any more stick than anyone else, although there was some grousing from Sarron’s Gauloises crew that the Michelins weren’t especially well suited to the bumpy Laguna Seca paving. Sarron. on hand courtesy of the French Army (which, in an expression of French civilization, sanctions the foreign excursions of its star biker, an arrangement that was reached after Sarron cut through the red tape by going AWOL a time or two to make a racing commitment) had nothing to say publicly regarding his tires, one way or the other.

continued from page 75

While the Formula 750 campaigners assessed the results of the final open practice sessions, the production Superbikes were being wheeled up to start the day’s warfare. McLaughlin, whose 845cc Suzuki was pumping out great gobs of horsepower. certainly looked like the man to catch, but he had some formidable companions on the front row of the grid: Pridmore on the Racecrafters Kawasaki, Neilson on his Ducati and Wes Cooley on the Yoshimura Kawasaki.

Without belaboring the point, let us make this observation about Steve McLaughlin’s ability to ride a racing motorcycle on pavement: He will go to almost any lengths to win, and gets away with antics that would have other men chewing the hay bales. His efforts to keep Neilson at bay magnified this characteristic. Although he was prepared to play a waiting game after McLaughlin smoked away into the middle distance in the early laps, Neilson found he was able to reel the Suzuki in on the tight parts of the course— McLaughlin spoke later of need for improvement in the Suzy’s brakes. Soon a pattern emerged. McLaughlin wuuld blast out to a slight lead in the fast part of the course until he got to the Corkscrew, where Neilson would close him up again. McLaughlin’s line never seemed to be the same through this section, and several times the Suzuki twitched ominously in the steep part of the downhill.

continued on page 94

continued from page 87

This went on for 15 of the race’s 20 laps, with Neilson putting the Ducati in striking position several times, but never quite getting past the Suzuki. Then McLaughlin, scraping the cases a little too vigorously in the fast left-handers, created an oil leak “where the alternator’s supposed to be.’’ as Neilson put it. With “wads” of oil flying back onto his face shield. Neilson was forced to drop back. “The closer 1 got to Steve’s bike, the less I could see." he said later. In the end. he was almost overtaken bv Pridmore. who made a stab at 2nd place in the final turn after flying along all by himself in 3rd through most of the race. Paul Ritter, riding what he calls a “Cook Neilson replica" Ducati, came home 4th, which he got after battling past Ron Pierce’s BMW and outlasting Cooley, who retired with a broken chain at the end of the 15th lap.

The addition of some prize money— McLaughlin pocketed $855,. Neilson $585, Pridmore $410. Ritter $365 and Pierce $320—certainly enhanced competitor interest in this event, which is always popular with spectators. The word among AMA factotums present at Laguna was that there will be more bucks for superbike competitors next year.

McLaughlin, who had also showed promise on his Formula 750 bike, was forced to scratch from the first heat of the feature with crankshaft difficulties, but the rest of the troupe was flagged off almost on time, and pole-sitter Romero was quickly relegated to the role of also-ran as Baker. Aksland and Hansford flew off to battle among themselves.

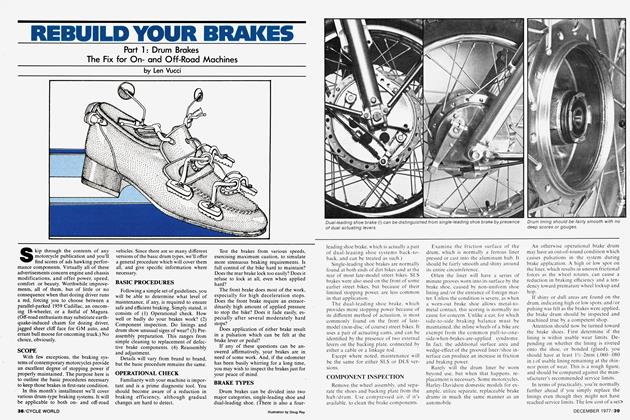

It quickly became clear that this wasn’t going to be a Baker parade, as Aksland not only closed up with the champ but began making it plain that he meant to pass. And after a couple of drag races on the start/ finish straight, he managed to do just that, inching past Baker between Turns 1 and 2. one of the fastest stretches on the course. In the process, Aksland set a new course record—1:10.20. 97.435 mph that was to stand until lap 1 1. when he'd set another. In all. Baker and Aksland trimmed time from the Laguna Seca outright motorcycle lap record five different times during the afternoon, finally getting it down to 1:09.47. 98.5 mph. But that came later.

Aksland continued to lead through middistance (16 laps), lowering the record twice more in the process, but he was unable to shake Baker. But by that time the leaders were beginning to encounter increasingly heavy traffic, and on lap 17 Aksland began to edge away as he put up his fastest lap of the day—1:09.58—and managed to get a couple backmarkers between himself and the champion.

Behind the leaders. Hansford had fallen slightly off' the blistering pace, but was still well in front of everyone else, that group being headed by Dave Aldana. who had overtaken Romero and was flying. Romero had fallen as far as 6th, behind Ron Pierce but climbed back to 5th by mid-distance and staved there. Pierce was followed by Dale Singleton. Sarron. Morales. Harry Cone and Nixon, who simply wasn’t getting enough power to dice with the faster bikes.

By lap 20. Aksland had put 4.2 seconds between himself and 2nd place, thanks to the vagaries of intervening traffic, and Baker eased his pace slightly, obviously beginning to think in terms of the second heat. In this frame of mind it rarely seems prudent to take chances, so when Baker found himself smack in the middle of a big gaggle of traffic in the closing laps he took his time, apparently unaware that Hansford was closing ground rapidly. This oversight had its consequence near the end of the 30th circuit when Hansford slipped past exiting Turn 9. He managed to hold Baker off through the next two laps to wind up 2nd. which is not what you'd call a bad opening round.

Aldana. a good way behind Baker but still considerably quicker than everyone else, came home 4th, Romero 5th. Singleton worked his way past Pierce to finish 6th. and Pierce, for his part, held off Sarron and Morales. Mike Baldwin rounded out the top 10.

As the Formula 750 bikes went off for various ministrations between heats, an intriguing field of vintage bikes gridded up for five laps of antique motorcycle racing. Although it was more parade than racemost of the riders were tip-toeing with these rare old-timers—it was good watching and. as Henry Manney observed, was “the first race all day that’s sounded like a race.’’ Of particular interest to CYCLE WORLD faithful was Buddy Parriot’s ride on a 1960 Norton Manx. Parriot showed up wearing Team CYCLE WORLD leathers dating to the early sixties and the fiveman assault on the Isle of Man. Unfortunately that year’s event was canceled.

In all. there were some 12 Nortons in the field, including Wes Cooley Senior's 1958 Manx, believed to be the first bike to lap the Isle of Man at over 100 mph. Some other interesting items on the docket: a 1954 Güera Saturno 500cc Single; a 1939 Mark VIII KTT Velocette; a 1919 Harley -Davidson 61 Twin; and a 1917 HarleyDavidson 8-valve Twin, a survivor from the wild days of the old board track speedways.

Then it was time to wheel the 750s out onto the grid again. There hadn’t been much in the way of patch-up heroics in the pits during the respite provided by the vintage bike show. However. Baker's bike did get one significant adjustment. During the first heat, the monoshock setting had been a tad low, which caused Baker to drag the exhaust in fast turns. This had been something of a problem all weekend on the bumpy Laguna course, but for the final heat the setting was finally right. There was also a fresh tire and slightly taller gearing in the lower cogs, to avoid wheel spin.

The final heat took some time to get underway, owing to confusion over grid positions for Sarron and Morales. Some enlightened soul in timing and scoring wanted Sarron to start 23rd after his 8th place finish, and the language barrier—a great deal of fractured French was blasted over the P.A. during the weekend—didn't help to promote a general understanding.

The hassles were finally resolved and the green flag was displayed, whereupon Hansford found some more magic in his Kawasaki and seized the lead with Baker in hot pursuit. Aksland. for his part, made a poor start, and wound up completing the first lap in 4th place, behind Romero. It took Aksland two more laps to find a way past Romero, bv which time Baker had seized the lead and was rapidly disappearing without so much as a fare-thee-well. Aksland struggled with the formidable Hansford through the sixth lap. finally squirting past in lap seven only to find that he'd all but lost contact with Baker, who was by that time 2.5 seconds downstream and going faster all the time.

On lap 10. Baker got around in 1:09.47 to crack Aksland’s course record from the first heat, and it began to be plain that the champ wasn't going to be caught again. Aksland. who had only to preserve his 2nd place position to wind up 1st overall, began to concentrate less on Baker and more on the wily Hansford, who didn't seem to have quite as much horsepower on tap as the leaders but nevertheless seemed always poised to strike. From that point on. it became a high-speed parade at the front of the pack.

Behind Hansford. Romeo motored along solidly in 4th. with some distance between himself and Aldana, w ho'd spent a big chunk of the second heat chasing Baldwin. Baldwin, in turn, had to deal with the hard-charging Morales to preserve 6th place. Sarron repeated his firstheat finish. Cooley came home a very creditable 9th (after starting 21st) and Sadao Asami. who'd started 12th. managed to crack the top 10.

When it was over. Baker could only reflect on his conservatism in the first heat traffic jam that allowed Hansford to get past and. as it developed, spoil his triumphant homecoming.

“There were so many people in that one group.” he said, “moving all over the place and evervthing, and we were right in the middle of’em. 1 guess 1 just waited around too long and Gregg sneaked past me.

“I wasn't really all that pumped for this race, but in the second heat I really felt I had to go. Between the heats my girlfriend came over and said. ‘Boy, they're saying a lot of bad things about you out there.’ so I knew 1 had to go faster.”

Aksland. who’d just beaten a world champion, was feeling understandably expansive. Asked if he thought his skill in cutting through traffic might have been superior to Baker’s, he was philosophical.

“Traffic.” he said. “Goin' through traffic is all luck.”

While Aksland, Baker and the remarkable Hansford were holding forth, the sidecars were going at it. Predictably, this went to the two surviving European rigs with Monnin/Weber finally prevailing over Steinhausen/Kalauch after the latter lost all gears save second. The event deflnitelv had its moments, such as the one that had hacks beetling all over the track trying to avoid Canadians Greg Cox and Bill Davidson w hen their Kawasaki engine seized exiting Turn 9.

Larrv Coleman and Wendell Andrews, the American champions, rode their Suzuki-powered rig to 3rd place, within sight of the front-place struggle but out of striking range.

Then it was time to go. a great cloud of bikers rising up out of the infield area and sailing off toward the various compass points. They may not have seen the international program they were led to expect, and the race had absolutely no bearing on the championship, but it would have been hard, perhaps impossible, to And any w ho wanted their money back. H3