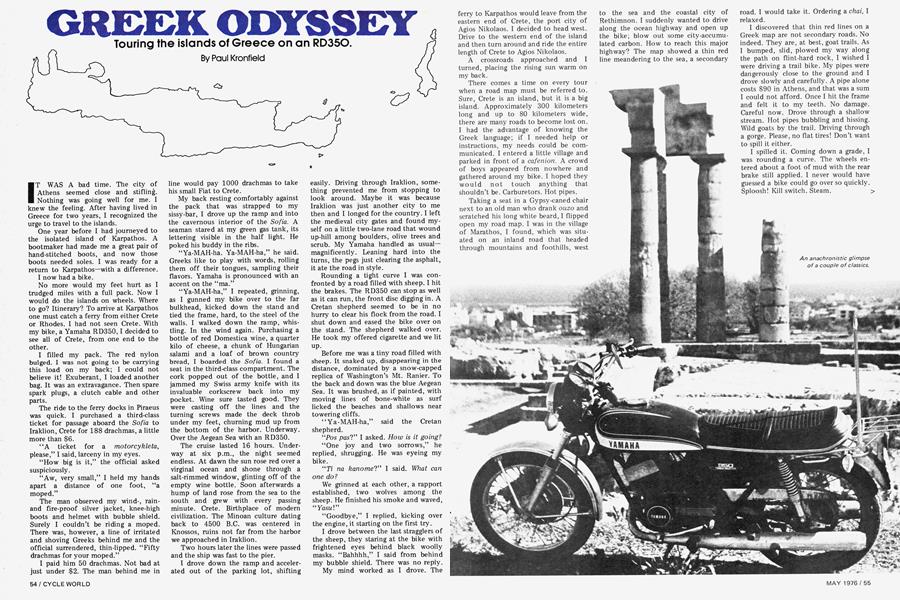

GREEK ODYSSEY

Touring the islands of Greece on an RD350.

Paul Kronfield

IT WAS A bad time. The city of Athens seemed close and stifling. Nothing was going well for me. I knew the feeling. After having lived in Greece for two years, I recognized the urge to travel to the islands.

One year before I had journeyed to the isolated island of Karpathos. A bootmaker had made me a great pair of hand-stitched boots, and now those boots needed soles. I was ready for a return to Karpathos—with a difference. I now had a bike.

No more would my feet hurt as I trudged miles with a full pack. Now I would do the islands on wheels. Where to go? Itinerary? To arrive at Karpathos one must catch a ferry from either Crete or Rhodes. I had not seen Crete. With my bike, a Yamaha RD350,1 decided to see all of Crete, from one end to the other.

I filled my pack. The red nylon bulged. I was not going to be carrying this load on my back; I could not believe it! Exuberant, I loaded another bag. It was an extravagance. Then spare spark plugs, a clutch cable and other parts.

The ride to the ferry docks in Piraeus was quick. I purchased a third-class ticket for passage aboard the Sofia to Iraklion, Crete for 188 drachmas, a little more than $6.

“A ticket for a motorcykleta, please,” I said, larceny in my eyes. “How big is it,” the official asked suspiciously.

“Aw, very small,” I held my hands apart a distance of one foot, “a moped.”

The man observed my wind-, rainand fire-proof silver jacket, knee-high boots and helmet with bubble shield. Surely I couldn’t be riding a moped. There was, however, a line of irritated and shoving Greeks behind me and the official surrendered, thin-lipped. “Fifty drachmas for your moped.”

I paid him 50 drachmas. Not bad at just under $2. The man behind me in line would pay 1000 drachmas to take his small Fiat to Crete.

My back resting comfortably against the pack that was strapped to my sissy-bar, I drove up the ramp and into the cavernous interior of the Sofia. A seaman stared at my green gas tank, its lettering visible in the half light. He poked his buddy in the ribs.

“Ya-MAH-ha. Ya-MAH-ha,” he said. Greeks like to play with words, rolling them off their tongues, sampling their flavors. Yamaha is pronounced with an accent on the “ma.”

“Ya-MAH-ha,” I repeated, grinning, as I gunned my bike over to the far bulkhead, kicked down the stand and tied the frame, hard, to the steel of the walls. I walked down the ramp, whistling. In the wind again. Purchasing a bottle of red Domestica wine, a quarter kilo of cheese, a chunk of Hungarian salami and a loaf of brown country bread, I boarded the Sofia. I found a seat in the third-class compartment. The cork popped out of the bottle, and I jammed my Swiss army knife with its invaluable corkscrew back into my pocket. Wine sure tasted good. They were casting off the lines and the turning screws made the deck throb under my feet, churning mud up from the bottom of the harbor. Underway. Over the Aegean Sea with an RD350.

The cruise lasted 16 hours. Underway at six p.m., the night seemed endless. At dawn the sun rose red over a virginal ocean and shone through a salt-rimmed window, glinting off of the empty wine bottle. Soon afterwards a hump of land rose from the sea to the south and grew with every passing minute. Crete. Birthplace of modern civilization. The Minoan culture dating back to 4500 B.C. was centered in Knossos, ruins not far from the harbor we approached in Iraklion.

Two hours later the lines were passed and the ship was fast to the pier. I drove down the ramp and accelerated out of the parking lot, shifting easily. Driving through Iraklion, something prevented me from stopping to look around. Maybe it was because Iraklion was just another city to me then and I longed for the country. I left the medieval city gates and found myself on a little two-lane road that wound up-hill among boulders, olive trees and scrub. My Yamaha handled as usual— magnificently. Leaning hard into the turns, the pegs just clearing the asphalt, it ate the road in style.

Rounding a tight curve I was confronted by a road filled with sheep. I hit the brakes. The RD350 can stop as well as it can run, the front disc digging in. A Cretan shepherd seemed to be in no hurry to clear his flock from the road. I shut down and eased the bike over on the stand. The shepherd walked over. He took my offered cigarette and we lit up.

Before me was a tiny road filled with sheep. It snaked up, disappearing in the distance, dominated by a snow-capped replica of Washington’s Mt. Ranier. To the back and down was the blue Aegean Sea. It was brushed, as if painted, with moving lines of bone-white as surf licked the beaches and shallows near towering cliffs.

“Ya-MAH-ha,” said the Cretan shepherd.

“Pos pas?” I asked. How is it going? “One joy and two sorrows,” he replied, shrugging. He was eyeing my bike.

“Ti na kanome?” I said. What can one do ?

We grinned at each other, a rapport established, two wolves among the sheep. He finished his smoke and waved, “Yasu!”

“Goodbye,” I replied, kicking over the engine, it starting on the first try. I drove between the last stragglers of the sheep, they staring at the bike with frightened eyes behind black woolly masks. “Bahhhh,” I said from behind my bubble shield. There was no reply.

My mind worked as I drove. The ferry to Karpathos would leave from the eastern end of Crete, the port city of Agios Nikolaos. I decided to head west. Drive to the western end of the island and then turn around and ride the entire length of Crete to Agios Nikolaos.

A crossroads approached and I turned, placing the rising sun warm on my back.

There comes a time on every tour when a road map must be referred to. Sure, Crete is an island, but it is a big island. Approximately 300 kilometers long and up to 80 kilometers wide, there are many roads to become lost on. I had the advantage of knowing the Greek language; if I needed help or instructions, my needs could be communicated. I entered a little village and parked in front of a cafenion. A crowd of boys appeared from nowhere and gathered around my bike. I hoped they would not touch anything that shouldn’t be. Carburetors. Hot pipes.

Taking a seat in a Gypsy-caned chair next to an old man who drank ouzo and scratched his long white beard, I flipped open my road map. I was in the village of Marathos, I found, which was situated on an inland road that headed through mountains and foothills, west to the sea and the coastal city of Rethimnon. I suddenly wanted to drive along the ocean highway and open up the bike; blow out some city-accumulated carbon. How to reach this major highway? The map showed a thin red line meandering to the sea, a secondary

road. I would take it. Ordering a chai, I relaxed.

I discovered that thin red lines on a Greek map are not secondary roads. No indeed. They are, at best, goat trails. As I bumped, slid, plowed my way along the path on flint-hard rock, I wished I were driving a trail bike. My pipes were dangerously close to the ground and I drove slowly and carefully. A pipe alone costs $90 in Athens, and that was a sum I could not afford. Once I hit the frame and felt it to my teeth. No damage. Careful now. Drove through a shallow stream. Hot pipes bubbling and hissing. Wild goats by the trail. Driving through a gorge. Please, no flat tires! Don’t want to spill it either.

I spilled it. Coming down a grade, I was rounding a curve. The wheels entered about a foot of mud with the rear brake still applied. I never would have guessed a bike could go over so quickly. Sploosh! Kill switch. Steam.

If one would have drawn a line starting at the top of my helmet and running down, neatly bisecting me and my bike into two equal halves, and then covered one half with a very thick coat of red mud, you would have an accurate representation of how we looked leaving the gorge and hitting the main coastal highway.

Rakk and Grutt. Me an’ me ruddy muddy bike. Followin’ the sea.

I rode for an hour; fifth gear, holding rpm at an even five grand. Cruising speed: 110 kph. Vibration was hardly noticeable, and the blast of salt-edged air was refreshing. I was passing every car I encountered, as they held the legal speed of 80. Unlike America, Greek police ignore motorcycles. They concentrate totally on cars. In cities, you can freely jump median strips, go the wrong way down one-wavs, park on sidewalks.

Time for a gas-up. I cringed as I pulled up to the púmp at a Shell station. Gasoline in Greece goes for 14 drachmas a liter. Sound cheap? That’s $1.83 a gallon. Super is $2.27. So filling my four-plus gallon tank costs an unbelievable $7.70! I’m glad I don’t burn octane. From now on I don’t want to hear moans from Stateside bikers about gas costing 60 cents a gallon.

My Yamaha manual has the following data: gasoline tank capacity 16

liters. Fuel consumption 35 kilometers per liter at 60 kilometers an hour. With the help of my Hewlett-Packard pocket calculator, I can report: consumption at

37.3 mph is 82.3 mpg. On a full tank, cruising range is 348 miles.

Well. . .after filling my tank at that Shell station and doing some quick figuring, I found that at 110 kph or

68.4 mph my RD350 had guzzled to the rate of 41 mpg. Not bad, but not too good, either. I had bought a two-stroke of moderate size for economy in the light of Greek gasoline prices. If I cruised at 40 mph though. . . .Naw! I decided to drop my cruising speed to 90-100 kph. Grin and bear it, the thirsty devil.

I hit the road, and half-way to Chania got a little thirsty myself. I stopped at an off-the-road tauerna where I was introduced to raki and Yannis Papachristopoulou.

I am no stranger to ouzo, retsina, chipora and other varieties of Greek beverage. I ordered an ouzo with a side plate of seafood goodies. All for 30 cents. The door opened and in walked the most outrageous character I have ever seen. From his wolf-grin down to his tennis shoes he filled the door. He was wearing a polo shirt, white shorts, and football-type knee socks. Villages and towns passed by in the next hour. Vrisse. Armen. Kafamion. Souda in the walls of a Venetian fort. I arrived in Chania. One of the larger cities of Crete, its harbor is ringed by old shops and buildings, gaudy in the sunshine. Flanking the harbor, a fort

“That your motorcycle out there?” he gestured over his shoulder with his thumb. I rose from my seat, alarmed. “Yeh, what’s wrong?”

He grinned. “Ya-MAH-ha.” “Ya-MAH-ha,” I let myself back down in my seat, relieved. He pulled a chair close to me, uninvited.

“That Ya-MAH-ha. . .it is kanone, yes?”

“Yes.” I agreed that my bike was a cannon.

“What are you drinking? Ouzo? Hell, you should drink Cretan drink,” he thumped himself solidly in the chest at the word “Cretan.”

“What’s that. . .chiporaV’

“ChiporaV’ He snorted, “No, my friend. Raki.” He ordered two rakis and shushed my protesting with his hands. “This is on me.” He grinned and a gold tooth sparkled as he peered at me from under his brows. The proprietor poured two half-tumblers from a five-gallon container and brought them to the table. The stuff smelled suspiciously like moonshine. We clinked glasses and sipped. It was like drinking from the business end of a blowtorch.

“That’s a good drink,” I rasped, uncrossing my eyes and feeling my stomach glow like a pot-bellied wood stove.

“Good? Good you say? It’s great! Kanone.” I stared at him as he drained his glass and stood up letting out a mournful howl. No one took any notice of his behavior.

“Maybe he’s the village idiot,” I thought.

“Well,” said Yannis Papachristopoulou, as he wolfed down my plate of seafood, “let’s hit the road.”

I was downright suspicious then. Mooching a ride? Hijacking a biker after plying him with liquid fire? He hitched up his knee shocks and guided me out the door. There on the cobbled street next to my bike was parked the oldest BMW I have ever seen. With a sidecar. In factory condition. I walked slowly around the BeeEm, noticing the preleading-link suspension. I searched for bullet holes in the sidecar; this bike must have seen service in the German army during the battle of Crete. I blinked and stared. The sidecar was filled to the top with ice, and poking their lovely snouts from the cubes were brown necks of full Amstel beer bottles. “You like my kanoneV’

“This is yours?” A new respect was building for this crazy man as he stood in the afternoon heat nodding like a proud father. “It’s beautiful. How old is it?” He shrugged. “And,” I continued, “what’s the, urn, sidecar for?”

“Come. I show you.” Yannis kicked it over. The old bike started immediately and idled with the slow, smooth and powerful throbs that only a BMW can produce.

(Continued on page 58)

Yannis lead the way back to the highway. We reached cruising speed. A few miles down the road we turned off. I watched the BeeEm negotiate the rough dirt road, jolting through potholes, ice cubes leaping from the sidecar. We shut down at the edge of a beach, and there, covering golden sands, were sunbathers. Mostly Scandinavian women. Nude.

I swallowed. They spotted our bikes, and, rising from their towels and blankets, they ran to us. I tried not to stare. We were in the midst of a crowd of tanned, blondehaired, lovely. ... I laughed. Yannis was selling beer and making, I guessed, quite a profit.

“Hello.”

I looked over to the young lady who stood like an Eve and smiled at me. Had she offered me an apple, I would not have been surprised.

“Hi. Nice day, huh?”

“I don’t speak English too well,” she

said, running her toes through the sand. “What’s your name?”

“Ingrid,” she laughed, showing strong white teeth, “what’s yours?” “Paul.” I was suddenly thirsty again. “May I buy you a beer?”

“Sure.” I walked over to the sidecar. Yannis winked at me slyly. “Two beers, kanone,” I said. He laughed, handed me two beers and refused my money.

My tour of Crete ended temporarily. Romance has no language barriers.

The next morning I wolfed down a breakfast of fried eggs and said goodbye to a very beautiful Ingrid Hansson from Stockholm. I made up my mind to see her on the return journey.

The day was bright and warm with a scent of blooming wild flowers. I headed west along the ocean. The countryside was changing. Whereas the area around Iraklion was dry, given to palms, olives and scrub, here there were pinecovered hills and mountains. The highway was hugging cliffs, winding, climbing. I followed the road around a curve and had to pull off to the shoulder. The view was spectacular. A bay of liquid blue was ringed by rugged cliffs. Beyond was an expanse of foothills covered by pine forests climbing to a majestic mountain capped with snow. It was idyllic. I felt like shouting, filling my lungs and letting go. Novels could be written here, symphonies composed.

I drove on, breathing air tinged with salt and pines.

(Continued on page 81)

Continued from page 58

stared out to sea, its huge stone blocks worn and pitted with time. Imposing.

I had a dinner of squid from the Cretan Sea, octopus slices, maridas fish that are eaten like french fries, head and all. Tsatziki, a tasty mixture of goat yogurt, cucumbers and garlic. Country bread, rough-ground and baked in outdoor wood-fired ovens. Retsina, the tangy Greek wine that is preserved with pine resin.

As I walked from the restaurant to my bike, I noticed a fellow sitting in the sun. He looked familiar. “Hi,” I said, “don’t I know you from somewhere?”

“I don’t think so,” he replied, grinning behind his beard. “I’m Paul Joppa.” We shook hands.

“Any relation to Frank Zappa?” I

asked

“Nope, but I sure dig BMWs,” he said.

I left Chania puzzled.

There was a sight I had heard much about, and it was nearby. I had to see it. Fifty-nine kilometers to the south, deep in the mountains of Lefka Ori, where some of the fiercest battles of World War II had been fought, is a gorge.

The Gorge of Samaria is the result of some cataclism. It must be; only a heaving explosion from the earth, or the scalpel of the god Zeus himself could have accomplished such an impressive rend in the earth. Rarangi Samarias, as it is called in Greek, is the largest gorge in Europe. It extends for 10 miles, from the heights of Lefka Ori south to the sea. Its walls are barely 12 feet apart, but it is 1000 feet deep.

I walked the trail down its length, constantly peering up at the blue slit that was the sky. It was quiet and semi-dark. The air was close and unmoving. All sounds-breathing, footsteps— echoed. There was a constant dripping of water. While the Grand Canyon is awesome in its grandeur, the Gorge of Samaria closed around you raises the small hairs on the back of your neck. You are in the mouth of the earth, walking between the rows of teeth.

The sea is a welcome sight when you emerge from the gorge. One never forgets the moss and lichen-covered walls of rock. There was a boat waiting in the surf for hikers. The only way out is by sea. Or a return up the gorge. I opted for the sea. I waded out through the light surf and boarded the kaique, climbing over the roughhewn gunwales. I wasn’t worried about my bike and belongings. There is no crime to speak of in Greece, particularly in Crete, the land of filotimo, honor.

The kaique moored at the village of Hora Sfakion. It is populated by one of the most ancient peoples of Europe. They are all fair-haired and blue-eyed. Their line hails from the Minoans, 4000 years back. They live in their village, fishing, baking bread, raising sheep. Hora Sfakion looks south across the Mediterranean Sea, an uninterrupted stretch of ocean, to the continent of Africa.

I rode a rickety, steaming, complaining bus back to my bike. Someone had placed a cage of roosters on the aisle seat next to me. One looked at me with his yellow, blinking eyes during the entire journey.

The bike was waiting for me, untouched, as I knew it would be. It was time to head east. I spent the night in Chania, and the next morning I was on the highway with a brimming tank and a destination of a beach and a certain Ingrid strong on my mind.

Halfway to my lady, the right plug fouled. My bike is plagued with many fouled plugs, and I took it in stride. I carried enough replacements to see me through my tour. I made a mental note to buy some Champion L3Gs, a plug with a wider heat range that is supposed to perform better in a bike with subquality coils. The RD350 is such a bike.

(Continued on page 114)

Continued from page 81

The day’s riding was good and the evening’s rest was ecstatic. Later, Yannis and his Danish girlfriend took us to an outdoor theater with folding chairs and a bedsheet for a screen. It was a poor English movie with Greek subtitles. It seemed that the Greek audience laughed always at the wrong places. Yannis had an ample supply of Amstel and the night passed too quickly.

The next morning I gave Ingrid my Athens address and said goodbye. I hate leave-takings. A motorcycle, however, the highway, and the blast of air help stimulate a short memory.

Back in Iraklion I explored a little. The town is composed of two parts. The new section with its tall buildings, fine shops, parks and squares. The old quarter containing a Venetian fortress, Gothic arches, churches, medieval walls and Turkish marketplace.

I drove to Knossos to view the ruins of the oldest kingdom in Europe, destroyed in 1400 B.C. by a cataclysmic earthquake and 100-foot tidal waves caused by the volcanic explosion of the nearby island of Santorini.

Back to the ocean and heading east. The road was a good asphalt highway following the contours of the coast in a series of serpentine bends—a pleasure on the 350. There were empty beaches, bays and plains sloping down to the sea.

I had to see Lassithi Valley and I was not disappointed. The plain, flanked by foothills and mountains, has 10,000 windmills leisurely churning the air. A little road zigzagged up the mountain until suddenly the whole plain spread out before me. Beautiful! I continued up the road, ending in Psychron. From there I made a two-hour trek up to Diktaeon Antron, the cave where Zeus is said to have been born. I found only bats.

Coming off the mountain, the day became gloomy with moisture-laden clouds skudding in from Africa. A light drizzle followed and I bundled up in waterproof pants and jacket. I was comfortable.

By the time I arrived in Agios Nikolaos, the weather had cleared and the sun came out with some late afternoon warmth. I bought tickets for the night ferry to Karpathos and waited for the sun to plunge and the stars to beckon for the ship.

At two in the morning, under the glare of dock-side mercury vapor lamps, my bike was hoisted in a sling to the cargo deck of the little ship. I raced aboard and climbed the ladder to see that no harm was done in loading the Yamaha, but the Greek deck crew sat her down, the centerstand gently kissing the deck. I wheeled her over to a bulkhead and tied her down. Should high seas be encountered, nothing, I hoped, would be damaged.

There were no high seas. The ride was pleasant and comfortable. I chatted with a party of Australians who were headed for Rhodes.

Karpathos to me is the Tahiti of the Greek islands. It is the most isolated of all locations in Greece, situated between Rhodes and Crete. It is a Tahiti, not because of waving palms and barebreasted natives it has none of these but because it is untouched by tourism. The island and its people live as they have lived for hundreds of years. Indeed, in my destination village of Olymbos, the people live in a matriarchal society and speak ancient Doric Greek!

The ship landed at the main port of Karpathos and my bike the largest motorcycle on the island was winched down to the pier. The first Yamaha ever on the island. A Japanese invasion of green tank, red pack, and silver-jacketed rider.

(Continued on page 118)

Continued from page 114

The map of Karpathos shows a dotted red line stretching from the end of the mountain road in the village of Spoa to Olymbos. A rough road or a goat trail? Could the Yamaha negotiate it?

No.

I found myself on a two-foot-wide ledge in rugged mountains with a jagged drop of two feet before me. A trail bike could have done it. The Yamaha RD350 could not. No room to turn around, I backed the bike carefully up the ledge, eyeing the 100-foot chasm so very close to the side.

A converted fishing kaique loaded my bike in the main port and we were underway with crates of tangerines, a side of beef, three goats and other goods. Seagulls wheeled over the wake as the boat chugged along the rugged coastline to the village of Diafony.

Three hours later we moored. Waves were lifting and thrusting the kaique against the crude concrete pier in the unprotected harbor. Timing the motion of the boat, I ran the bike to the pier. Now I was in familiar territory. This untouched island of proud men and women was like a second home and a refuge from the big city. I drove along the path bordering the river to the dirt

and gravel sometimes-path, sometimesroad that wound up and over the spine of the mountains. At times, I could barely make the grade. I was determined and the Yamaha made it every time. I rounded a final bend and parked to gaze on Olymbos.

Clinging to the summit and sheer sides of a young mountain, the village has a terraced valley spread at its feet. Terraces strongly resembling those of rice paddies in the Far East. The flavor of the majesty of Olymbos is that of a village in the Andes. The dress and style of living is so similar you catch yourself looking for llamas.

The path followed the contours of the mountains and climbed to Olymbos. I felt eyes on me. The villagers have a clear view of the road-path, and my bike, its engine working at 5-6000 rpm in second gear, was most likely heard across the valley. I waved to women leading donkeys down the trail. They nodded and the lead donkey twitched his long ears.

I had finally reached my goal. The bootmaker remembered me. I had slept in his shop it doubles as an inn and we had sipped many chiporas together. He unrolled a sleeping pad for my use. I made my bed under shelves laden with cured leather and suede. He eyed my boots and clucked his tongue.

“I will give you soles that will last for 10 years.” He took the boots and I put on my tennis shoes. I believed him. He was inspecting a piece of leather that must have been a good three-quarters of an inch thick. “You know there is a wedding tonight?” he asked.

“Oh?”

“A xeni is always welcome.” Xeni is the Doric Greek word for stranger.

The blast of shotguns at the groom’s house signaled the beginning of a ceremony and a feast that would not end for three days and three nights. The village band played: a lyra, a kind of violin with three strings and held vertically, a laouta, a pot-bellied oversized guitar played with a bird’s quill, and tsambouna, a crude bagpipe made of goat skin. These instruments, coupled with the wailing Doric Greek singing, sounded older than the silence of the surrounding mountains. A man shot off a Mauser over the valley and its echoes in the falling night were as loud as the initial report.

From the other side of the village a volley of shots cracked. The bride’s house. Two processions wound their way to the church. The bride and the groom. The bride had $80,000 worth of gold coins hanging from her neck and shoulders, covering her body to her hips her prika, the dowry. It would never be spent. It is passed on from mother to daughter through the generations. The couple entered the church bright with icons and candles.

I cannot describe the feast, the mountains of food, the endlessly flowing wine and chipora. I cannot paint the picture of that church clinging to the edge of a cliff that dropped 1000 sheer feet to the sea. The singing. Dancing. People sleeping in the late hours with their heads resting on their arms on a table covered, straining with food, only to wake and begin to eat and drink again.

Karpathos and Olymbos were the final magic touches to a motorcycle tour of islands as old as Western man.

As I left Karpathos a week later, on board a boat headed for the civilization of Rhodes and Athens, I felt melancholy over parting with the unspoiled people, the majesty, the strong ties with the past.

The Yamaha had given me my most memorable journey, a true tour of the oldest islands of Greece. I don’t think my boots will wear out for at least 15 years.

I stood on the gently rising and falling deck of the ship, next to my bike, and watched the sun touch the watery horizon in a brilliant sunset. A Greek passenger sidled over and smiled in the twilight.

“Ya-MAH-ha,” he said. “Ya-MAH-ha,” I repeated, laughing.