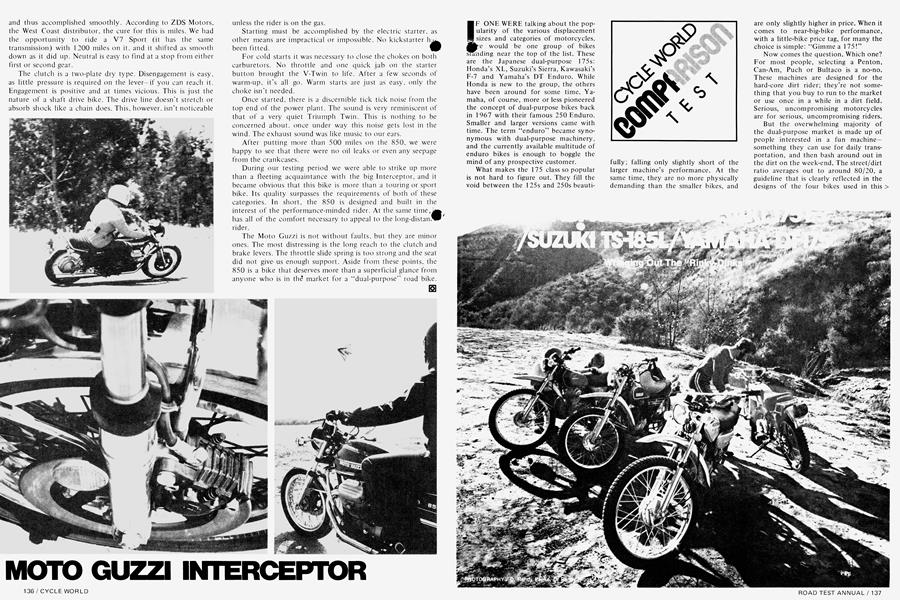

HONDA XL175/KAWASAKI 175 /SUZUKI TS-185L/YAMAHA DT175

CYCLE COMPARISON TEST

IF ONE WERE talking about the popularity of the various displacement sizes and categories of motorcycles, e would be one group of bikes standing near the top of the list. These are the Japanese dual-purpose 175s: Honda’s XL, Suzuki’s Sierra, Kawasaki’s F-7 and Yamaha’s DT Enduro. While Honda is new to the group, the others have been around for some time. Yamaha, of course, more or less pioneered the concept of dual-purpose bikes back in 1967 with their famous 250 Enduro. Smaller and larger versions came with time. The term “enduro” became synonymous with dual-purpose machinery, and the currently available multitude of enduro bikes is enough to boggle the mind of any prospective customer.

What makes the 175 class so popular is not hard to figure out. They fill the void between the 125s and 250s beauti-

fully; falling only slightly short of the larger machine's performance. At the same time, they are no more physically demanding than the smaller bikes, and are only slightly higher in price. When it comes to near-big-bike performance, with a little-bike price tag, for many the choice is simple: “Gimme a 175!”

Now comes the question. Which one? For most people, selecting a Penton, Can-Am, Puch or Bultaco is a no-no. These machines are designed for the hard-core dirt rider; they’re not something that you buy to run to the market or use once in a while in a dirt field. Serious, uncompromising motorcycles are for serious, uncompromising riders.

But the overwhelming majority of the dual-purpose market is made up of people interested in a fun machinesomething they can use for daily transportation, and then bash around out in the dirt on the week-end. The street/dirt ratio averages out to around 80/20, a guideline that is clearly reflected in the designs of the four bikes used in this comparison. They’re built for the average rider to have fun on in a practical way, not to race a motocross with.

With that in mind, the CYCLE WORLD staff got deeply into one of the most time-consuming tests we’ve ever done. It was also one of the most surprising, informative, and fun.

ABOUT THE PROCEDURE

Each machine was ridden by the staff as daily transportation during a period of a few weeks, was carefully broken in and serviced according to manufacturers’ requirements. Measurements were taken, bonus points were tallied and the machines were trucked to Orange County International Raceway for the pavement performance sessions. Each distributor was allowed the opportunity of having a mechanic or tuner present at the drag strip, to insure that their machine was running to its capacity. Yamaha and Suzuki showed up, Kawasaki and Honda did not. An entire day was spent at the strip with the comparison bikes. Three riders rode every machine to insure accuracy.

Once the street performance of each bike was thoroughly evaluated, we headed for the dirt. Again the machines were checked out to ensure that they were running up to snuff. The only items that we removed were the rear turn-indicator lights and the mirrors. Tires, although they were not proper all-out dirt items, remained standard.

The bikes were in completely stock form when we tested them.

The dirt segment of our comparison would include a four-mile enduro course, a hill climb, a whoop-de-doo sandwash run and a drenching water test. Riders included Bob Atkinson, Jody Nicholas and D. Randy Riggs. Two runs per rider on each bike was in effect on all but the water test. Here fearless Editor Atkinson submitted his bod to the soaking by making four passes with each machine through the wet. The performance testing results were scored on a 4-3-2-1 basis; bonus points and ease of maintenance points were awarded singly for each item.

ABOUT THE BIKES

Probably the most interesting aspect of this particular test is the fact that each bike has a totally different engineering concept, yet they are all designed for basically the same market. The Honda is the only four stroke in the test; the others are two-strokes. However, the Suzuki is a conventional piston-port Single, the Kawasaki uses a rotary valve and the Yamaha a reed valve induction system. Seems as though everyone has their own idea about the way motorcycles are supposed to work. That’s part of the reason that our sport is anything but dull.

HONDA’S XL

Unlike the larger 250 and 350 XL four-stroke Singles, the 175 uses a simple two-valve arrangement with a chain driven overhead camshaft. Crankcases are made from aluminum alloy and sidecovers are magnesium. A steel liner is cast in the aluminum cylinder—most of the inside pieces follow design practices of the SL-125.

The slide-needle 26mm Keihin carburetor provided instant starting and a smooth idle throughout the test. In fact, the trusty XL sat out overnight in a 20 degree snowstorm. When the frozen mass of metal was uncovered next morning, it had the audacity to fire^k on the first kick.

Clutch pull is light, and the gearbox just about faultless. Missed shifts were generally caused by rider error. Overall, the bike could easily be called mechanically impressive. Construction quality, finish and execution of design on this bike are perhaps the best of any in the bunch.

Sitting on the XL gives one a stretched out impression, yet there’s a definite Honda feel. Even a slight Elsinore touch comes through. The wheelbase is the longest of the group, and the seating position is just about right for both short and tall riders. A narrow overall width (the engine is just 11.5 in. wide), contributes to good clearance in the tight stuff out on the trail. It also enables a rider to stand on the folding, cleated footpegs without interference from any appendage.

Anyone with a modicum of sen^ who rides dirt seriously, will fit an accessory brand skid plate. As is, there is no protection for the downswept pipe, magnesium sidecases or the rear bottom side of the engine. A low ground clearance of 7.8 in. makes the proposition almost essential.

The little XL will spin around town merrily, happy and content as long as the rider keeps things below about 7000 rpm (slightly more than 50 mph in high gear). Past that point, vibration takes over in both the pegs and bars, and makes the rider feel as though he is plundering his machine into destruction. One of our staffers makes a 10-mile haul home every night on what is mostly a nice stretch of open coastal highway. Here the 175 would buzz into the redline with the throttle to the stop in top gear; the engine never seemed to mind.

Cornering, braking and overall street stability make it an extremely safe machine amid the four-wheeled beasts, as long as the rider keeps in mind the cornering limitations of trials universal tires. You can push it somewhat through a bend, but not too much, or it’ll be gravel rash time. Good instrumentation, lighting and mechanical and exhaust silence add to the overall packaee.

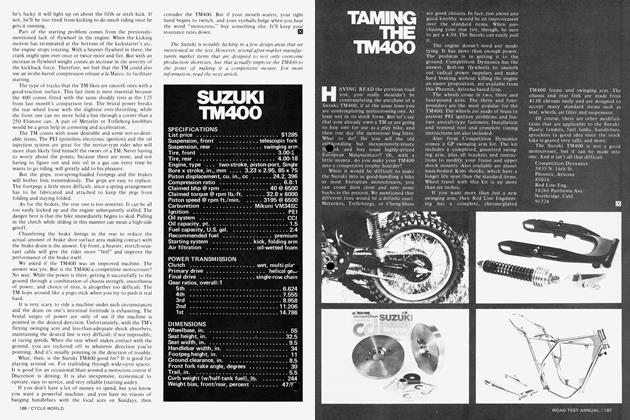

SUZUKI TS-185L

Our last test of Suzuki's 185 came about two years ago. Since that time, the machine has undergone a host of improvements, one of the most notable being a change from a 19 in. to a 21 in. front wheel. The machine is still light, in spite of the addition of turn indicators and larger diameter front fork legs. And, the exhaust is quieter, though still the loudest of the comparison hikes. There are many important touches, like a more convenient ignition switch placement and a flexible plastic front fender: it’s the Volkswagen of the class. Good to begin with, but better each year. Suzuki can hardly complain either. The 185 outsells all of its other models by a considerable margin.

The 183cc piston-port Single is the most cold-blooded engine of the group. Though only a prod or two of the kick starter is needed to bring the engine to life, it begs for the use of the choke for several minutes. And it never really runs well until the unit is thoroughly warm.

Again, like the Honda, the 185 is comfortable and accommodates riders of varying size well. It sits a bit higher off the ground than the Honda, but has roughly equal high-speed stability over bumpy ground.

On the highway, it’s easier to live with at cruising speeds than both the Honda and Yamaha, and is about equal to the Kawasaki. In town, however, the engine pops and snorts and four-strokes until the throttle is opened fairly wide. It doesn't care much for slow running through traffic. Suzuki should also do something about deadening the sharp popping sound reverberating from the insides of the exhaust system. Most of the racket emanates from that point; otherwise it's mechanically quiet.

The Sierra utilizes the same rear hub as the Kawasaki and Yamaha; the rear brakes are identical, as well. On the Suzuki, pavement braking felt spongy and the front unit is none too strong. A glance at the data panels will show how superior the Honda was to all of the bikes in this category.

We had a few major bitches about the 185 that we feel Suzuki should take steps to remedy. The biggest hassle is with the air cleaner. It’s virtually a major job to get to, remove and service the filter element. And once you complete that portion, getting the thing back in brings tears to the eyes. Fortunately, the unit does its job well; even water has trouble finding its way in.

Handgrips are the miserable waffle pattern variety; footpegs are rubber and not suitable for off-road use. And, as long as we're speaking of sins, a glaring one has to be the difficult-to-removeand-replace lighting system. Pulling the turn indicators off the Sierra is someone's idea of a bad joke, and there is simply no excuse for it on a dual-purpose motorcycle. While it does have a few faults, a strong second place finish in the test showed how good a machine it really is.

KAWASAKI 175 F-7

In stock form, the rotary valve Kawasaki is probably capable of putting out more horsepower than any machine in the class, it'll even snuff several 250s we know of, but some of its capability is hampered by a combination of minor flaws.

Of the four comparison bikes, the “Kow" was the most comfortable in street use. Vibration through the pegs and bars was less than that of the other three, and the F-7 could be cruised at higher speeds. On the minus side, its handling was less than positive when pushed around a corner (forks and frame felt as though they were flexing), and hard braking was not that reassuring.

Each year it appears that Kawasaki improves its quality control a degree; this year is no exception. Although the “Kow” was not as well finished off as the Honda or Yamaha, it did rival the Suzuki's overall finish. A few “MicT^É Mouse” items come to mind, such mí poor handgrips, footpegs that constantly loosen and rotate, a steel front fender with a beer-can-like attachment brace and useless little chains that are supposed to prevent fouling foot controls with trail debris.

F-7s are heavy they are wide, as well. Yet Kawasaki is to be commended for keeping engine width to a minimum, in spite of the rotary valve. This year they made the unit even slimmer by redesigning the carburetor and side case. Conveniences such as oil injection, primary kick starting and decent electrical components are included with the little two-stroke; just as with the Yamaha and Suzuki. The Honda four-stroke doesn't need the oil injection, of course, and no one on earth could imagine a late model Honda without a start-in-any-gt^^ feature.

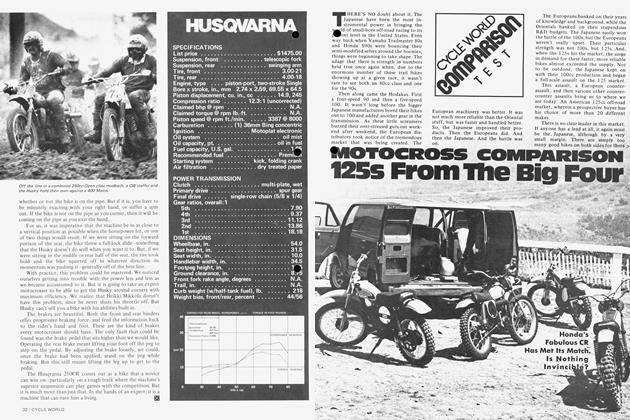

YAMAHA DT-175

Although Yamaha has produced a> 175 “Enduro” for some time now, the ’74 version is almost totally new. Before the test was started, the Yamaha looked to be the most promising bike of the foursome. It turned out to be the most disappointing.

Frame design is now patterned after that of the production motocross machinery. Probably one of the major benefits of the change is an exhaust system that is tucked completely out of the rider’s way. The DT-175 is physically smaller than its competitors. Hence, it is the lightest, but also the most uncomfortable for an average size rider. It feels more like a 100 than a 175.

Our staffers range in size from 5 ft. 7 in. and 130 lb. to 6 ft. 1 in. and 205 lb. Not one of us was really comfortable on the DT. The main reaction seemed to be: “If it was just a little bigger.”

Styling-wise, the Yamaha comes off looking pretty good. The paint, chrome and polished pieces are flawless; the same goes for the wiring. Interestingly enough, this was the third Yamaha off-road machine we’ve tested recently that had its sidestand break off at the point where it’s welded to the frame rails. Something must be wrong with the attachment welds because we certainly haven’t been abusing the stands.

In spite of the cramped riding position, the DT-175 gets around town nicely. First gear is so low that it’s a bunch easier to pull away from traffic lights in second. The short wheelbase makes low-speed handling very nimble, but not as stable as the other three test machines at higher speeds. And, as can be seen by the figures printed in the data panel, street braking was less than satisfactory.

The DT comes standard with a luggage rack mounted over the rear fender...just like the Kawasaki. Headlight illumination at night was poor, but none of the other machines were much better in this respect.

STREET SUMMARY

The Honda XL-175 won this category hands down due to its superior performances in braking and acceleration. It delivers excellent fuel economy, is not the least bit fussy about slow running, and handles as well as it’s tires will let it. Comfort is good as long as the speed is kept below 50 mph; above that the Kawasaki delivers less vibration and is smoother. But the Kawasaki doesn’t deliver the same stopping power, and handling is mushy.

As for the Suzuki and Yamaha, the Suzuki would have to be rated very close to the Kawasaki. It handles better, braking is about the same, but it’s slower. In addition, it isn’t as smooth at highway speeds and doesn’t care much for slogging along in traffic...and it’s too loud. The Yamaha is the solid loser here. It’s too small to be comfortable, braking is poor and performance takes a back seat to the other machines. But the DT is nimble at low speeds.

IN THE DIRT

Our four-mile enduro course was laid out at Saddleback Park and encom passed terrain that you wouldn't be lieve. The loop was designed to wrin out the machinery and the riders. rode like we would in an enduro if we were behind time. In other words, at about 85 or 90 percent. In the end, our speed averages came out close to 26 mph, so we actually were running on the fast side of things, if you were to consider a typical enduro.

HONDA

XL175

$740

KAWASAKI

175 F-7

$729

SUZUKI

TS-185L

$795

YAMAHA

DT-175

$832

There were rocky sections, fast fire roads, steep climbs, eyeball bulging downhills, tight trails, a sandwash and one portion where the rider had to squeeze through a rock ledge and make an off camber right-hand turn from nearly a dead stop...straight up a narrow rutted path.

The hillclimb was fairly long, but allowed a build-up of speed before the incline was hit. Each bike was straining hard near the top.

In the sandwash, suspension was an important factor, along with power and tires. None of the machines were confidence-inspiring here, regardless of the times they turned in.

Considering the price of each machine in the test, it’s not really surprising to see the absence of a few important items for serious dirt riding. All four bikes come with flimsy steel rims—some have rimlocks, some don’t. Only the Honda has proper cleated footpegs and good grips. It also has the best quick-disconnect lighting system in the group. Each machine has a flip-up seat, but the Honda and Kawasaki require the ignition key to get their’s open. That’s bad. The Yamaha allows the rider to leave the seat locked or unlocked, and the Suzuki has no lock at all.

No serious off-roader will be happy with any of the bikes suspension-wise, but the Honda comes the closest to acceptability, followed by the Suzuki, Yamaha and Kawasaki. Both the Honda and Suzuki need a switch from a 2.75 to a wider 3.00 x 21 in. tire at the front, and it would be interesting to see how off-road performance would change on the Yamaha and Kawasaki if they had 2 Is instead of 1 9s.

Out on the course, the Honda suffered most from its lack of low-end “grunt.” Climbing hills from a near standstill means the rider has to slip the dutch to get the rpm up to near 7000; then it pulls fine and has no tendency to pick up the front end. Wheelies on the Suzuki and Yamaha were difficult to control on steep uphills. But both had no difficulty with low-end power, as the Kawasaki did.

Higher speed stability, aided in no small way by the long wheelbase, was the Honda’s forte. If it had more power, it would be the “slider” of the group. Downhill runs hurt the Suzuki the most. A badly chattering rear brake and weak front brake were the bases of the problem.

Kawasaki’s F-7 pulls like a Mule on a towpath. Unfortunately, the rear shocks belong in a garbage pail, and the Hatta adjustable forks flex badly. Kawasaki has an optional fork brace for the bike; we would wholeheartedly suggest one. The forks are infinitely adjustable, but arriving at the right combination of spring tension, axle position etc., is well out of the realm of the average rider. A good set of conventional forks would be a better proposition.

Ever see a dog wag it’s tail? That’s what the F-7 does over whoop-de-do^^ In our sandwash run the KawasJ^P provided many unwanted thrills for the riders. But it’s engine makes up for what it lacks in other areas.

Yamaha isn’t lying when they talk about their reed-valve improving low and mid-range performance. Our test bike wanted to climb walls. But it’s chassis is too small, the rider is squeezed into a Yoga position and the engine has no top end. A rider 5 ft. 9 in. or taller will find it most uncomfortable to stand on the pegs. The Yamaha feels like a Mini. But sitting down isn’t much better, since the padding in the seat is almost nil and isn’t big enough for a flea’s butt. Higher speeds are spooky because the handling is so quick and the suspension is on the stiff side. Too bad Yamaha didn’t try their Thermal-Flow shocks on this one.

Where the Yamaha is fun is on.A really tight trail, but again, as long the rider is on the small side. It’s light weight and narrow width makes it even more maneuverable in this type of situation.

In the dirt, the Honda and Suzuki were very close. Both bikes in standard form are unquestionably superior in off-road performance than the two others. The Honda has a speed edge on the Suzuki, in spite of the latter’s larger displacement. It’s edge was readily apparent in the hillclimb and of course at the drag strip.

Ultimately, the charts and data panels tell the story. Honda’s XL-175, by virtue of obtaining the best street and off-road scores, is unquestionably the winner. You can buy better off-road bikes with no dual-purpose pretentions for more money, but for under $800 you’ll have a hell of a time findj|Ä anything that can match it on an onv off-road basis. It’s the best motorcycle in the class: Our testing proved that. A pig it is not, and anyone who makes that claim is the one who goes “Oink!”

We were so impressed with the XL, in fact, that we’re going to keep the machine for a year and turn it into the off-roader that it is capable of being. We’ll keep you posted on what we do in the way of maintenance and upkeep, and all of the costs involved. m

View Full Issue

View Full Issue