FEED BACK

Readers, as well as those involved in the motorcycle industry, are invited to have their say about motorcycles they own or have owned. Anything is fair game: performance, handling, reliability, service, parts availability, lovability, you name it. Suggestions: be objective, be fair, no wildly emotional but illfounded invectives; include useful facts like mileage on odometer, time owned, model year, special equipment and accessories bought, etc.

A WORD TO THE WISE

The tattoo of letters from customers more shocked than angry at the motorcycle parts problem is only the tip of the logistical iceberg. Occasionally someone like Mr. David Chinn (CW, May, 1975), tries to tell “the dealer’s side” of the problem, which is that the problem is caused by everybody but the dealer himself. Instead of sucking their thumbs and sniveling about the manufacturer and distributor and customer, dealers could take constructive action to meliorate the parts problem.

1. Through their organization, dealers can urge the manufacturer towards greater parts standardization and commonality, thus eliminating part of the problem at its source.

2. They can urge the manufacturer to place a wallet-sized card in the registration-papers pocket of each motorcycle giving all identification data needed to buy parts for that individual bike and telling the owner to take the card with him when he goes parts shopping.

3. The customer who doesn’t have the necessary I.D. for his bike probably doesn't know it and never heard of it until it’s arrogantly demanded by some haughty and scornful parts man. Such customers need educating, not browbeating. The parts man can be trained to give a little set speech before demanding the data, explaining why he needs it.

4. A dealer can devise his own motorcycle (and customer) I.D. form, have it printed on 4x6 cards, have the customer fill out a card, and can keep it on Continued from page 24

(Continued on page 26)

file at the parts counter. The potential for goodwill, sales building, repeat sales, mutual convenience, lowered return rate, and the elimination of acrimony over whether the customer or the parts man misidentified the bike is obvious. Parts sold for, or service done on, the bike could be noted on the back of the card. Handing the card to be taken home and filled out with serial numbers, etc. to a customer who innocently believes “red Honda” is enough to identify the correct ignition points helps convince him of the reality of the problem and thus defuses his suspicions of the parts man’s indolence or incompetence. Once his card is on file, he can send even his scatterbrained sister-in-law to pick up parts, and know he’ll get the right ones. When the parts man checks a card on file, he can then call the customer by name—the importance of which may be lost on order-takers, but never on salesmen.

5. Mr. Chinn implies that the customer has a duty to fit his lunch break to the convenience of the dealer’s lunch breaks, which is silly since it’s the dealer’s business—literally, his business— to fit his staffing to the flow of customers.

6. Since customers don’t like to wait in line, at least some of them would shift their visits from rush hours to slack periods if they knew which were which. A simple sign at the parts counter, showing the peaks and valleys by hour and day, would tend to level the flow of business and thus to benefit everyone.

Motorcycle dealers cannot cure the parts problem, but they can do much to alleviate it, and that’s precisely their job, their business, their livelihood—not the customers’. “The customer is always wrong” is no defense in bankruptcy court, which, save for civil war itself, is the leading implement of consumer sovereignty. A dealer can always entice customers, but not always coerce them, and if he tries, he will fail, not because of the zealotic squawking of Naderite consumerists, but because customers silently leave and never return. The dealer who will not learn the easy way, from the experience of others, that the consumer is the most generous of all masters, and the crudest, will then learn the hard way, by his own experience, that consumer sovereignty is ultimate, absolute, remorseless and final.

J. G. Krol Anaheim, Calif.

THE BIG GOUGE

You guys make me laugh! I mean I really laugh when I read letters in your “Feedback” column such as the one from Mr. Murphy in your March issue. He bought a 1972 machine and is simply elated with his bike because in his two years of ownership he has only had to replace rings, a piston, a fender and spark plugs, in addition to the "standard" items. What are these standard items? Points maybe, possibly a chain and sprockets?

(Continued on page 28)

Continued from page 26

Or the letter in your I~ebruary issue from Mr. Fowler who, within a paltry 4300 miles on his Suzuki, is so surprised that he has had no major problems with his bike that he feels compelled to write to a national publication.

Do I sound cynical, a little bitter? Let me tell you why. I am a motorcycle mechanic in a very successful dealership in southern Ontario that carries two major brands of Japanese motorcycles. Bikes, in Canada anyway, are grossly overpriced to begin with. (Prospective customers come in with a rolled up copy of CYCLE WORLD and, smacking it on the sales desk, demand to know why we are charging $3499 for their dream machine when you say it costs only $2849). But that is not my beef.

A customer knows when he buys a bike that he is also supporting a national motocross and road racing team, na tional advertising, and an extensive warranty program. It's not until after he has bought his bike that the owner finds out that the manufacturer has him by the wallet. He then finds out that, since he has bought a performance machine, his bike needs points, plugs and con densers at 3000-mile intervals (as one three-cylinder model in particular does), a chain and sprockets at 7-8000 miles, pistons, rings and a rebore at 10-12,000 miles. Suddenly the economy of his small "basic transport/fun bike" dwindles, and this is the big gouge.

since motorcyciing is so seasonal, dealers are forced to charge a 40-percent or higher markup on parts, and service rates as high as $1 5 per hour to put food on their tables during the slack months of the year. It is sad to see, and believe me, everyday I see a customer's jaw drop when he's charged $40 for one shock absorber for his 125cc after he just had four heavy-duty shocks in stalled on his Ford for less than that.

You really feel the big gouge when, after .one year's riding, you return your bike to the dealer to sell it. The dealer then tells you that, even though you just spent $200 on an originally $1500 machine, you can only be allowed $900 towards the purchase of this year's latest technological breakthrough. This is because, although it has new pistons and tires, it still has 10,000 miles, and the paint is faded, the alloy and chrome are corroded, it needs cables, sprockets, etc.

(Continued on page 30)

Continued from page 28

I wish that I could look the other way, but I can’t, it’s my living. Oh, what do I ride? I ride a BMW R69/S, 1967, 45.000 miles. I replace tires every 12.000 miles, plugs every 1 5,000, points every 25,000 and change drive-shaft oil every 16,000 miles. It looks the same as the day I bought it. It cruises vibrationfree at 80 mph for 600-mile days, and takes me across the country and back with the only maintenance being oil changes. Ugly, hah, I like it.

Jim Cooper Mississauga, Ont., Canada

EVALUATING THE 250 EXACTA

Perhaps some of my fellow readers may be interested in my experience with a Suzuki RL250 Exacta. The bike came ready for trials work, but before any serious riding was done, a day was spent shaping the machine to my personal tastes. This included changing the oil in the gearbox and forks, lubricating anything that moves (cables, rear chain, etc.), adjusting brakes, setting tire pressure (seven front, six rear), greasing the edges of the air filter element to keep any dirt from coming in around the edges, and sealing the airbox with silicone seal to keep the water out. A set of Doherty grips and an in-line fuel filter were also added. This whole job takes an evening to complete, but it is an evening well spent making sure everything is perfect.

My first trials bike taught me a lot about my new bike; the tires were junk (not flexible enough and of much too round a profile to grip anything), it needed to be geared lower, the gas cap leaked (the factory had pushed the rubber gasket up too far), and when the bike falls on the left side, the petcock sticks out far enough to break. Turning the petcock solves that trouble. The tank also dents easily.

The next day, a trip back to the dealer got me nothing but a promise that all the parts would be ordered. After that, a lot of time was spent running back and forth as the parts slowly trickled in. I missed three trials in the process of waiting for the petcock. A 58-tooth rear sprocket solved the gearing problem. The dealer said the tires would come in a month or so (Dunlop two-ply).

The following three months were spent riding four trials, the Gordon Farley Trials School, a couple of weekends helping to set up a trial that our club (Great Lakes Trials Club) was holding, as well as a couple of trips up North and some local practice. During this time, further modifications were performed. These included cutting the fork stops down with a hacksaw, drilling holes in the footpegs to help mud pass through, heating and bending the kickstand closer to the swinging arm, and lowering the needle to get rid of a tiny flat spot way down low.

(Continued on page 32)

Continued from page 30

After each event the bike is gone over thoroughly—cables lubed, air filter cleaned, chain removed and cleaned, hubs and spokes cleaned. This whole process only takes an hour or so and gets the bike ready for the next trial.

Other than the trouble with the petcock (really my own fault), the RL has been totally reliable; it’s even on the original spark plug. Just pour gas in and run it.

My gripes are few and pretty minor. Every time the bike is ridden in mud the clutch pushrod becomes coated with mud, making the clutch lever almost impossible to pull. Taking the sidecase off, removing the mud and lubing the pushrod will bring the nice easy pull back. This goes for all Suzooks, so if your clutch becomes hard to pull, cleaning and lubing the pushrod will help; don’t forget the cable too.

The silencer comes loose from the bracket; so far a piece of plastic tubing slipped on the end and held with a couple of hose clamps has worked in stiffening up the mounting and cutting down the exhaust that leaks around the joint and covers the shock with oil.

The skid plate needs to be both stronger and wider to cover all the exposed parts of the engine. Also, don’t forget to turn the chain oiler off every time you stop or there will be a big mess to clean up when you get back.

Other than these things, the bike seems well put together. Once it is changed a little bit and the rider gets used to the power (it’s just a little snappy) and the quick steering with the light front end, the RL Suzuki becomes a decent trials bike. It’s no Sherpa T, but it gets the job done without a lot of maintenance and parts hassles; isn’t that enough?

Happy Wobbling.

Jack Edwards Utica, Mich.

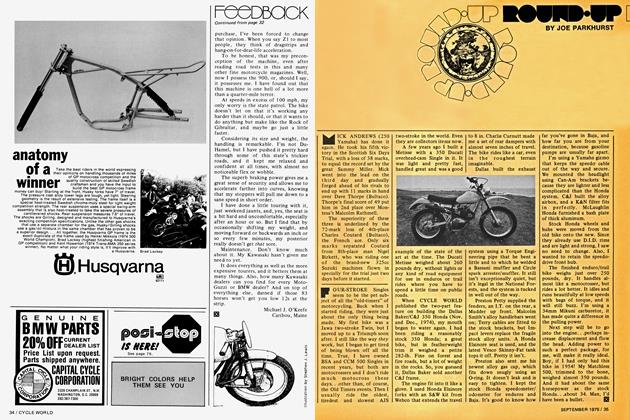

NEW Z1 OWNER

I own a new 1975 Kawasaki 900 ZIB. I had previously owned a 1971 CB750 Honda, and, at the time, I was convinced that there wasn’t a more durable, troublefree, better performing mount, for the price, built anywhere. Not even in Germany. With my new purchase, I’ve been forced to change that opinion. When you say Z1 to most people, they think of dragstrips and hang-on-for-dear-life acceleration.

(Continued on page 34)

Continued from page 32

To be honest, that was my preconception of the machine, even after reading road tests in this and many other fine motorcycle magazines. Well, now I possess the 900, or, should I say, it possesses me. I have found out that this machine is one hell of a lot more than a quarter-mile terror.

At speeds in excess of 100 mph, my only worry is the state patrol. The bike doesn’t let on that it’s working any harder than it should, or that it wants to do anything but make like the Rock of Gibraltar, and maybe go just a little faster.

Considering its size and weight, the handling is remarkable. I’m not DuHamel, but I have pushed it pretty hard through some of this state’s trickier roads, and it kept me relaxed and confident at all times, with almost no noticeable flex or wobble.

The superb braking power gives me a great sense of security and allows me to accelerate farther into curves, knowing that my stoppers will pull me down to a sane speed in short order.

I have done a little touring with it, just weekend jaunts, and, yes, the seat is a bit hard and uncomfortable, especially after an hour or so. But I find that by occasionally shifting my weight, and moving forward or backwards an inch or so every few minutes, my posterior really doesn’t get that sore.

Maintenance. Don’t know much about it. My Kawasaki hasn’t given me need to yet.

It does everything as well as the more expensive tourers, and it betters them at many things. Also, how many Kawasaki dealers can you find for every MotoGuzzi or BMW dealer? And on top of everything else, darned if those 83 horses won’t get you low 12s at the strip.

Michael J. O'Keefe Caribou, Maine

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontOn the Snell Memorial Foundation Helmet Test

September 1975 -

Letters

LettersLetters

September 1975 -

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

September 1975 By Joe Parkhurst -

Preview

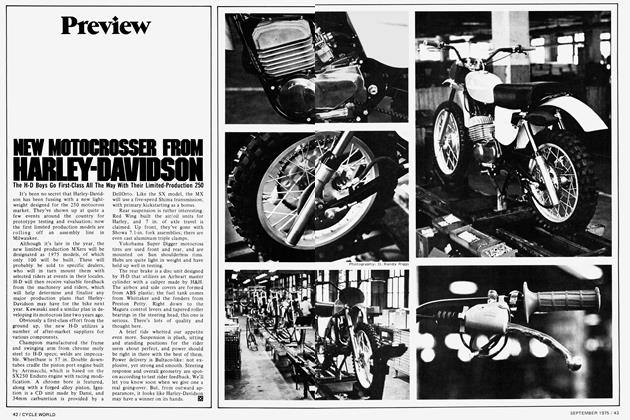

PreviewNew Motocrosser From Harley-Davidson

September 1975 -

Competition

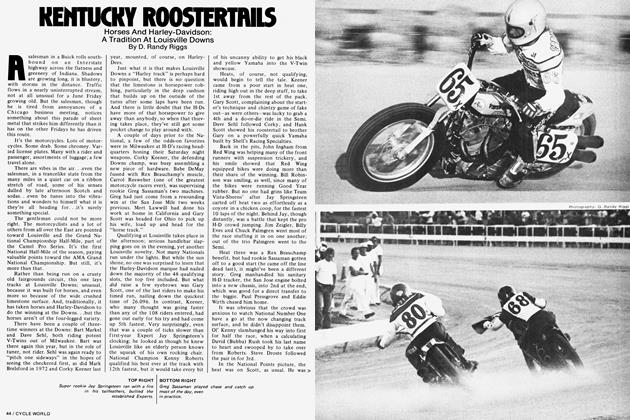

CompetitionKentucky Roostertails

September 1975 By D. Randy Riggs -

Features

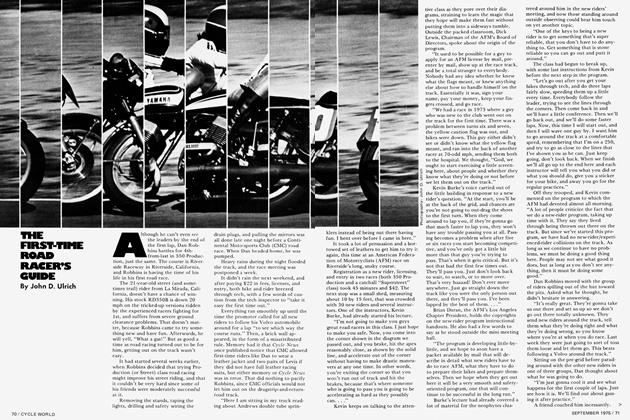

FeaturesThe First-Time Road Racer's Guide

September 1975 By John D. Ulrich