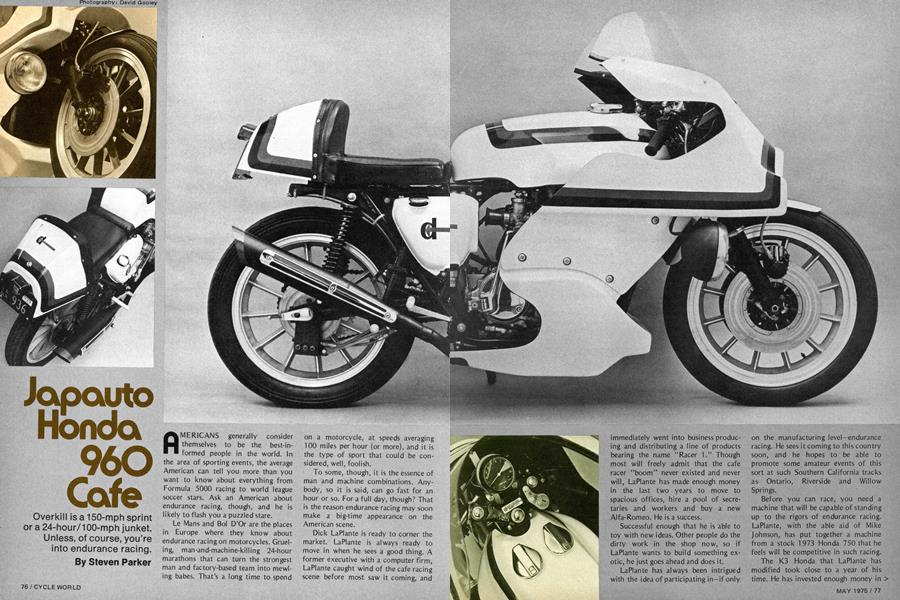

JAPAUTO HONDA 960 CAFE

Overkill is a 150-mph sprint or a 24-hour/100-mph junket. Unless, of course, you're into endurance racing.

Steven Parker

AMERICANS generally consider themselves to be the best-in-formed people in the world. In the area of sporting events, the average American can tell you more than you want to know about everything from Formula 5000 racing to world league soccer stars. Ask an American about endurance racing, though, and he is likely to flash you a puzzled stare.

Le Mans and Bol D’Or are the places in Europe where they know about endurance racing on motorcycles. Grueling, man-and-machine-killing 24-hour marathons that can turn the strongest man and factory-based team into mewling babes. That’s a long time to spend on a motorcycle, at speeds averaging 100 miles per hour (or more), and it is the type of sport that could be considered, well, foolish.

To some, though, it is the essence of man and machine combinations. Anybody, so it is said, can go fast for an hour or so. For a full day, though? That is the reason endurance racing may soon make a big-time appearance on the American scene.

Dick LaPlante is ready to corner the market. LaPlante is always ready to move in when he sees a good thing. A former executive with a computer firm, LaPlante caught wind of the cafe racing scene before most saw it coming, and immediately went into business producing and distributing a line of products bearing the name “Racer 1.” Though most will freely admit that the cafe racer “boom” never existed and never will, LaPlante has made enough money in the last two years to move to spacious offices, hire a pool of secretaries and workers and buy a new Alfa-Romeo. He is a success.

Successful enough that he is able to toy with new ideas. Other people do the dirty work in the shop now, so if LaPlante wants to build something exotic, he just goes ahead and does it.

LaPlante has always been intrigued with the idea of participating in—if only on the manufacturing level—endurance racing. He sees it coming to this country soon, and he hopes to be able to promote some amateur events of this sort at such Southern California tracks as Ontario, Riverside and Willow Springs.

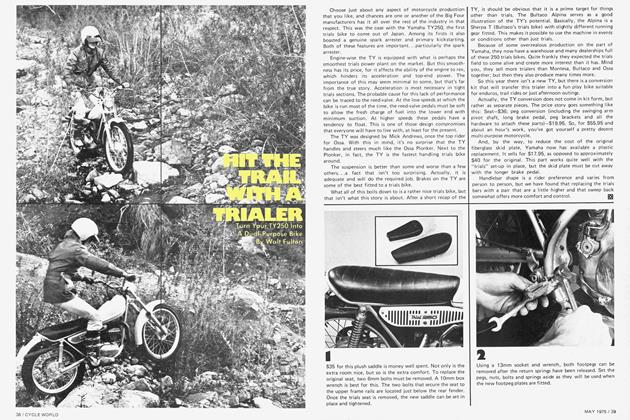

Before you can race, you need a machine that will be capable of standing up to the rigors of endurance racing. LaPlante, with the able aid of Mike Johnson, has put together a machine from a stock 1973 Honda 750 that he feels will be competitive in such racing.

The K3 Honda that LaPlante has modified took close to a year of his time. He has invested enough money in it so that he “could buy an MV Agusta if I wanted”. About six thousand bucks and a year of time. What came of all this?

japauto/Honda

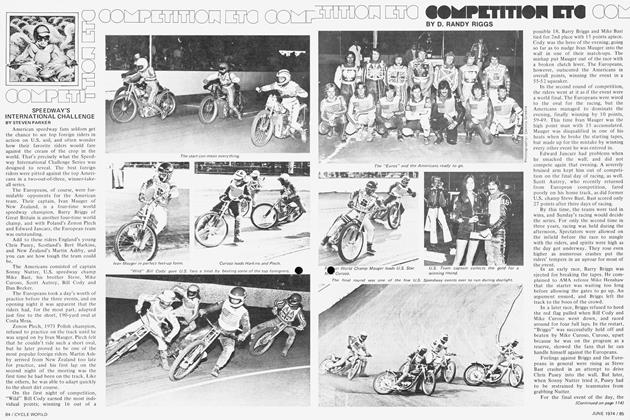

A very impressive~looking machine. Striking in both engineering design and mechanical function, it is the only machine of its type in the United States. Painted in white, black and red with the "Dick's Cycle West" logo emblazoned on it, the machine looks all business. If an American wanted to design an endur ance machine, this would probably be it.

The Honda’s frame is stock, with some modification performed on the swinging arm. LaPlante, hoping to eventually market his “swinging arm secret,” wouldn’t tell us what the trick was. Suspension on the machine consists of Koni rear shocks. They are, says LaPlante, “rebuildable, and will save us some money.” For the front forks, heavier-than-normal springs have been added and LaPlante has used a 40-weight ATF fluid and sealer to keep the springs moist. He is also tight-lipped about the suspension system, apparently wanting to wait until he can market the bike in kit form.

Some of the machine is available now from LaPlante as a kit. The seat and tank arrangement is available from “Cycle West” and will fit all 750 Hondas. The tank is unusually large and holds 5.5 gal. of fuel. The fuel tank is equipped with twin fuel caps to allow speedy fill-ups during racing. The seat is mounted on the Honda hinges and will open. There is also a storage area (lockable) in the rear of the seat. Fully one inch of foam padding gives the rider something comfortable to sit on, while the seat allows accessibility to electrics and air breather elements on the big machine.

The front fender is designated by LaPlante as “my funny fender.” Its flared shape funnels cool air from the front of the machine directly into the oil cooler mounted in front of the engine. A Hurst-Lockhart cooler is utilized. Below the front fender LaPlante has added an extra Honda disc brake for added enormous stopping power. LaPlante likes to keep things stock when possible. Indeed, his large fuel tank fits right on the stock frame and uses the fuel petcocks found on the machine when you buy it.

The fairing, of course, is the most eye-catching feature of the bike. Manufactured in France by Japauto and then customized by LaPlante for the Honda, the fairing offers full wind protection for the rider when in race position, and also allows access to the oil filter, pipe collector and oil cooler.

The fairing is not available at this time for sale, and LaPlante refers to it as a “one-shot deal. I did this one and I don’t plan on doing many more in the near future.”

Hanging from the fairing are two Cibie H-4 quartz-iodine lighting instruments. These lamps can throw a beam powerful enough to provide visibility for up to two miles. They are, of course, illegal in this country and can be used only on race tracks or in off-road situations. They also draw enormous amounts of power, forcing LaPlante to rewire the Honda and set in special switching instruments for the lights.

The engine on the motorcycle has been punched out to 960cc with a kit from Japauto of France. Capable now of speeds in excess of 150 miles per hour, when properly geared, the engine sports new pistons, cylinders, valves, guides and other standard engine “performance increasers”. The bike responds> in kind. Reacting much like a race machine, the four-stroke has had added to it a new dimension of power and performance, making the first-time rider feel that if endurance racing is practiced in this country, LaPlante’s machine will be a winner.

Japouto/HondQ

LaPiante has gone out of his way to keep things “stock” on this bike. Stock brakes (in front, with a disc in the rear), even stock passenger pegs. The originalequipment heat cover is used on the pipes, and engine supply systems are also factory items. Carburetion is normal for a 750 Honda, although the engine now uses 1 8mm spark plugs. The rear fender can also be saved, although LaPiante elected to cut his a bit short.

Problems? Mainly in starting the machine. The engine, with its increased size, has become a burden on the battery. This, added to the powerrobbing headlights, serves to make the 750, or 960, if you will, a real electricity drainer.

Although it is now geared at 17:48, front to rear, LaPiante hopes to install 18:45, utilizing a rear sprocket from a 750 Suzuki. Cruising speed? Its creator estimates that the machine will be capable of 95-plus mph for 24 hours. And the machine will still be in one piece after that time.

While this Honda may not be the endurance bike to end all, it is a step in the right direction for a person interested in getting Americans interested in long-distance endurance racing. Certainly LaPiante has a stake in it all; but if his visions are as correct as they were in the cafe racing market, you’d better start building your very own endurance machine tomorrow.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue