TOOT TOOT TOOTSIE, GOODBYE

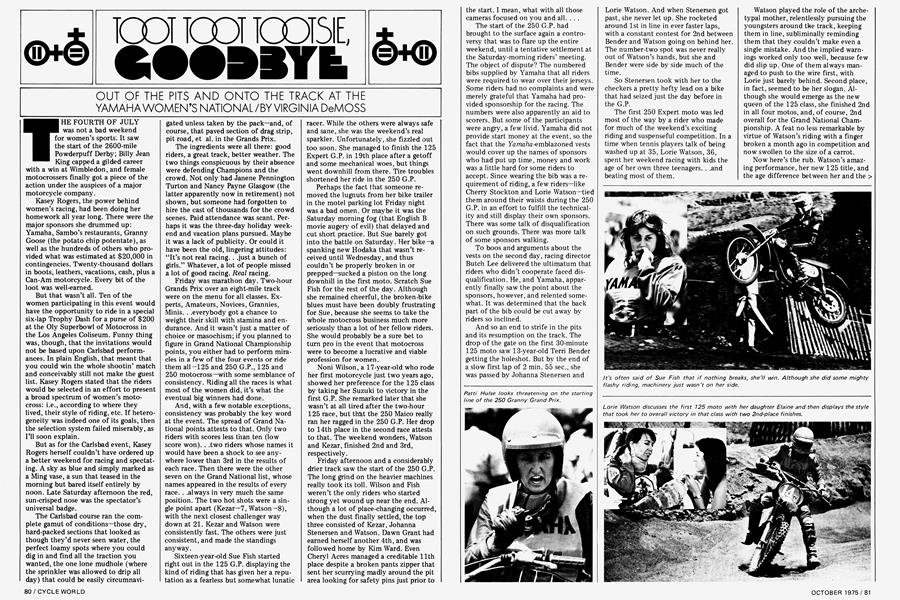

OUT OF THE PITS AND ONTO THE TRACK AT THE YAMAHA WOMEN’S NATIONAL/BY VIRGINIA DeMOSS

THE FOURTH OF JULY was not a bad weekend for women’s sports. It saw the start of the 2600-mile Powderpuff Derby; Billy Jean King capped a gilded career with a win at Wimbledon, and female motocrossers finally got a piece of the action under the auspices of a major motorcycle company.

Kasey Rogers, the power behind women’s racing, had been doing her homework all year long. There were the major sponsors she drummed up: Yamaha, Sambo’s restaurants, Granny Goose (the potato chip potentate), as well as the hundreds of others who provided what was estimated at $20,000 in contingencies. Twenty-thousand dollars in boots, leathers, vacations, cash, plus a Can-Am motorcycle. Every bit of the loot was well-earned.

But that wasn’t all. Ten of the women participating in this event would have the opportunity to ride in a special six-lap Trophy Dash for a purse of $200 at the Oly Superbowl of Motocross in the Los Angeles Coliseum. Funny thing was, though, that the invitations would not be based upon Carlsbad performances. In plain English, that meant that you could win the whole shootin’ match and conceivably still not make the guest list. Kasey Rogers stated that the riders would be selected in an effort to present a broad spectrum of women’s motocross: i.e., according to where they lived, their style of riding, etc. If heterogeneity was indeed one of its goals, then the selection system failed miserably, as I’ll soon explain.

But as for the Carlsbad event, Kasey Rogers herself couldn’t have ordered up a better weekend for racing and spectating. A sky as blue and simply marked as a Ming vase, a sun that teased in the morning but bared itself entirely by noon. Late Saturday afternoon the red, sun-crisped nose was the spectator’s universal badge.

The Carlsbad course ran the complete gamut of conditions—those dry, hard-packed sections that looked as though they’d never seen water, the perfect loamy spots where you could dig in and find all the traction you wanted, the one lone mudhole (where the sprinkler was allowed to drip all day) that could be easily circumnavigated unless taken by the pack—and, of course, that paved section of drag strip, pit road, et al. in the Grands Prix.

The ingredients were all there: good riders, a great track, better weather. The two things conspicuous by their absence were defending Champions and the crowd. Not only had Janene Pennington Turton and Nancy Payne Glasgow (the latter apparently now in retirement) not shown, but someone had forgotten to hire the cast of thousands for the crowd scenes. Paid attendance was scant. Perhaps it was the three-day holiday weekend and vacation plans pursued. Maybe it was a lack of publicity. Or could it have been the old, lingering attitudes: “It’s not real racing. . .just a bunch of girls.” Whatever, a lot of people missed a lot of good racing. Real racing.

Friday was marathon day. Two-hour Grands Prix over an eight-mile track were on the menu for all classes. Experts, Amateurs, Novices, Grannies, Minis. . .everybody got a chance to weight their skill with stamina and endurance. And it wasn’t just a matter of choice or masochism; if you planned to figure in Grand National Championship points, you either had to perform miracles in a few of the four events or ride them all—125 and 250 G.P., 125 and 250 motocross—with some semblance of consistency. Riding all the races is what most of the women did, it’s what the eventual big winners had done.

And, with a few notable exceptions, consistency was probably the key word at the event. The spread of Grand National points attests to that. Only two riders with scores less than ten (low score won). . .two riders whose names it would have been a shock to see anywhere lower than 3rd in the results of each race. Then there were the other seven on the Grand National list, whose names appeared in the results of every race. . .always in very much the same position. The two hot shots were a single point apart (Kezar—7, Watson -8), with the next closest challenger way down at 21. Kezar and Watson were consistently fast. The others were just consistent, and made the standings anyway.

Sixteen-year-old Sue Fish started right out in the 125 G.P. displaying the kind of riding that has given her a reputation as a fearless but somewhat lunatic racer. While the others were always safe and sane, she was the weekend’s real sparkler. Unfortunately, she fizzled out too soon. She managed to finish the 125 Expert G.P. in 19th place after a getoff and some mechanical woes, but things went downhill from there. Tire troubles shortened her ride in the 250 G.P.

Perhaps the fact that someone removed the lugnuts from her bike trailer in the motel parking lot Friday night was a bad omen. Or maybe it was the Saturday morning fog (that English B movie augery of evil) that delayed and cut short practice. But Sue barely got into the battle on Saturday. Her bike-a spanking new Hodaka that wasn’t received until Wednesday, and thus couldn’t be properly broken in or prepped—sucked a piston on the long downhill in the first moto. Scratch Sue Fish for the rest of the day. Although she remained cheerful, the broken-bike blues must have been doubly frustrating for Sue, because she seems to take the whole motocross business much more seriously than a lot of her fellow riders. She would probably be a sure bet to turn pro in the event that motocross were to become a lucrative and viable profession for women.

Noni Wilson, a 17-year-old who rode her first motorcycle just two years ago, showed her preference for the 125 class by taking her Suzuki to victory in the first G.P. She remarked later that she wasn’t at all tired after the two-hour 125 race, but thht the 250 Maico really ran her ragged in the 250 G.P. Her drop to 14th place in the second race attests to that. The weekend wonders, Watson and Kezar, finished 2nd and 3rd, respectively.

Friday afternoon and a considerably drier track saw the start of the 250 G.P. The long grind on the heavier machines really took its toll. Wilson and Fish weren’t the only riders who started strong yet wound up near the end. Although a lot of place-changing occurred, when the dust finally settled, the top three consisted of Kezar, Johanna Stenersen and Watson. Dawn Grant had earned herself another 4th, and was followed home by Kim Ward. Even Cheryl Acres managed a creditable 11th place despite a broken pants zipper that sent her scurrying madly around the pit area looking for safety pins just prior to the start. I mean, what with all those cameras focused on you and all. . . .

The start of the 250 G.P. had brought to the surface again a controversy that was to flare up the entire weekend, until a tentative settlement at the Saturday-morning riders’ meeting. The object of dispute? The numbered bibs supplied by Yamaha that all riders were required to wear over their jerseys. Some riders had no complaints and were merely grateful that Yamaha had provided sponsorship for the racing. The numbers were also apparently an aid to scorers. But some of the participants were angry, a few livid. Yamaha did not provide start money at the event, so the fact that the Yama/ia-emblazoned vests would cover up the names of sponsors who had put up time, money and work was a little hard for some riders to accept. Since wearing the bib was a requirement of riding, a few riders—like Cherry Stockton and Lorie Watson—tied them around their waists during the 250 G.P. in an effort to fulfill the technicality and still display their own sponsors. There was some talk of disqualification on such grounds. There was more talk of some sponsors walking.

To boos and arguments about the vests on the second day, racing director Butch Lee delivered the ultimatum that riders who didn’t cooperate faced disqualification. He, and Yamaha, apparently finally saw the point about the sponsors, however, and relented somewhat. It was determined that the back part of the bib could be cut away by riders so inclined.

And so an end to strife in the pits and its resumption on the track. The drop of the gate on the first 30-minute 125 moto saw 13-year-old Terri Bender getting the holeshot. But by the end of a slow first lap of 2 min. 55 sec., she was passed by Johanna Stenersen and Lorie Watson. And when Stenersen got past, she never let up. She rocketed around 1st in line in ever faster laps, with a constant contest for 2nd between Bender and Watson going on behind her. The number-two spot was never really out of Watson’s hands, but she and Bender were side by side much of the time.

So Stenersen took with her to the checkers a pretty hefty lead on a bike that had seized just the day before in the G.P.

The first 250 Expert moto was led most of the way by a rider who made for much of the weekend’s exciting riding and suspenseful competition. In a time when tennis players talk of being washed up at 35, Lorie Watson, 36, spent her weekend racing with kids the age of her own three teenagers. . .and beating most of them.

Watson played the role of the archetypal mother, relentlessly pursuing the youngsters around the track, keeping them in line, subliminally reminding them that they couldn’t make even a single mistake. And the implied warnings worked only too well, because few did slip up. One of them always managed to push to the wire first, with Lorie just barely behind. Second place, in fact, seemed to be her slogan. Although she would emerge as the new queen of the 125 class, she finished 2nd in all four motos, and, of course, 2nd overall for the Grand National Championship. A feat no less remarkable by virtue of Watson’s riding with a finger broken a month ago in competition and now swollen to the size of a carrot.

Now here’s the rub. Watson’s amazing performance, her new 125 title, and the age difference between her and the > rest of the riders made it triply preposterous that she was omitted from the field of ten invited to take part in the Superbowl exhibition. And even if you ignore her showing at Carlsbad, what of the premise that the invitations would provide a broad representation of the infinite variety that is women’s racing? A broad representation? Most of them just a few years apart in age, all but two from Southern California? Although Watson’s participation in the Superbowl would have been questionable, since she would possibly be undergoing surgery on her finger at that time, failing to extend her an invitation was inexcusable. A 125 race without the class Champ? Absurd.

And Lorie was about to prove her supremacy in the 250 class, too, until she was passed by Kezar coming down that long hill in the fifth lap. Teri was effortlessly proving herself just a little bit better on the bigger bikes. Linda Stanley and Cherry Stockton crossed the line 3rd and 4th, positions they would reverse in the second 250 moto.

Apparently still inflated from her first 125-moto victory, Johanna Stenersen let her dead-serious intentions be known by grabbing the holeshot in the second, only to be stricken with a flat rear tire not more than a few minutes into the race. She continued doggedly, nonetheless, dropping to 4th place by the third lap, and down to 6th by the fifth go-round. She ultimately retired from the fray with an out-of-balance two-race record of 1/27.

Following Johanna around in the initial laps were Watson, Oregonian Nancy Thomas, and Terri Bender. Thomas, thwarted by sundry crashes last year, and by a broken bike that kept her from riding most of this year’s first moto, wasn’t content to follow anyone for long. Riding with goggles that had slipped down around her neck rigjit near the start, Thomas scooted past Watson on the 3rd lap, never to be repassed. Her DNF in the first moto gave her a lopsided record to match Stenersen’s: 27/1.

But there was also some pretty exciting racing going on behind the leaders. Teri Kezar, uncharacteristically all the way back in 6th place, began knocking off anybody and anything that ran in front of her. First Stenersen on the sick bike, then a dice with Noni Wilson and a pass. Whoosh, past Terri Bender and into 3rd. Still not content, Kezar even went past Watson for a time, but Lorie, now pretty well programmed to take 2nd, soon regained that position. To the white flag, evenly spaced a few yards apart, it was Thomas, Watson, Kezar. The final lap was simply an instant replay.

That repass of Kezar by Watson did an interesting thing. It evenly matched the two for Grand National points, making the final 250 moto a high-pressure tiebreaker. Obviously not a graduate of the Hitchcock School of Mystery, however, Kezar didn’t leave anybody in doubt long. She led right out of the gate. The start found Watson remiss, and she was forced to follow Cherry Stockton and Linda Stanley, who were a solid 11 seconds behind Teri the Turtle. But Watson wasn’t forgetting the tie that easily. She picked off Stanley and Stockton and set her sites on Kezar. Lorie was riding like crazy, but so was Teri. And there was still that 11-second lead. Click. Make that 15 seconds. Click, 22. Click, 23. When Teri Kezar crossed the finish line, there was an agonizingly long pause before Lorie followed her.

So, by a single point, Kezar had taken it all. But it happened just the way Hollywood would have written it: a tied contest battled for by the two front riders, right down to the wire.

There was much talk during the two days at Carlsbad about whether Yamaha would pick up the Women’s National Motorcycle Championships again next year. If it doesn’t, someone else would be wise to. Slightly more than half of the world’s population is female; that’s one tremendous market—as yet largely untapped—for motorcycles and related paraphernalia. And this has been the first program on such a large scale to appeal to that market.

But more than intelligent marketing, the Women’s National Motorcycle Championship is a racing event on a national level to which women can look forward to riding when they get good. Before there was nothing. Last year there was the Powderpuff National Championships. This year that gooey title was dropped. Progress has been made. Next year there will probably be more. Good riders will never again have to hide behind insipid titles like “Powderpuff” and acronyms like “PURR” (Powderpuffs Unlimited, Riders and Racers) to prove that they are women. Women who happen to be just as good as the other half of the population at racing motorcycles. Today a little more freedom from some silly, ages-old stereotypes. Tomorrow the World Championship? Í51

RESULTS

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Letters

LettersLetters

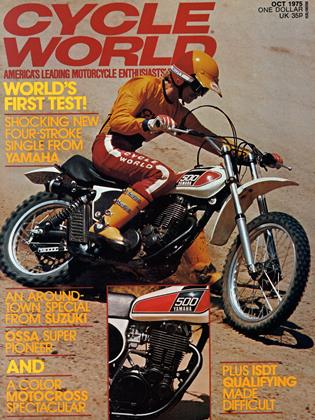

October 1975 -

Departments

DepartmentsFeed Back

October 1975 -

Departments

DepartmentsRound·up

October 1975 By Joe Parkhurst -

Features

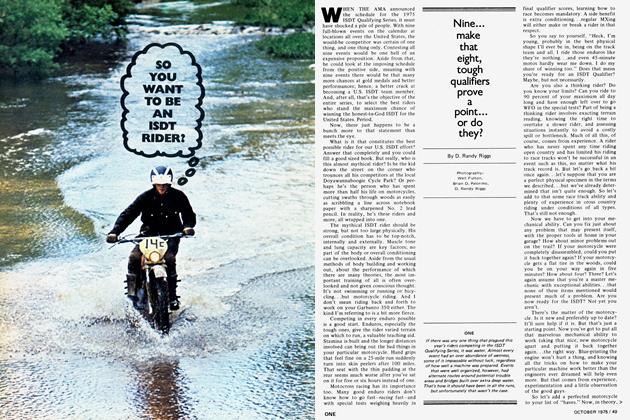

FeaturesSo You Want To Be An Isdt Rider?

October 1975 By D. Randy Riggs -

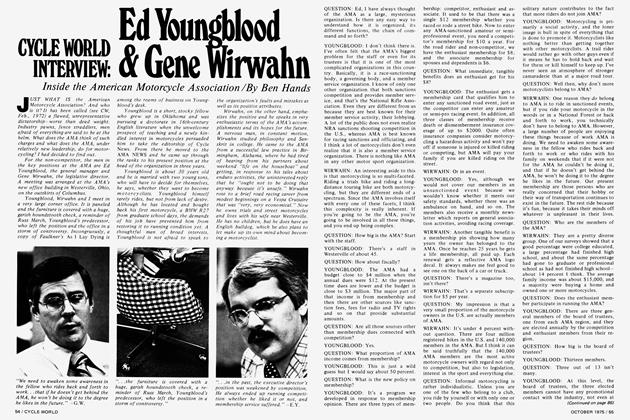

Cycle World Interview

Cycle World InterviewEd Youngblood & Gene Wirwahn

October 1975 By Ben Hands -

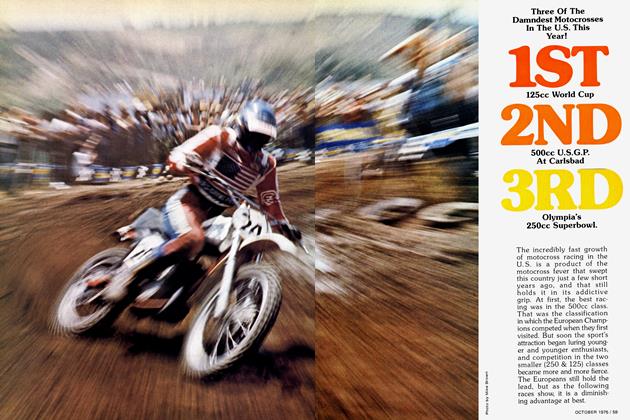

Special Competition Feature

Special Competition FeatureThree of the Damndest Motocrosses In the U.S. This Year!

October 1975