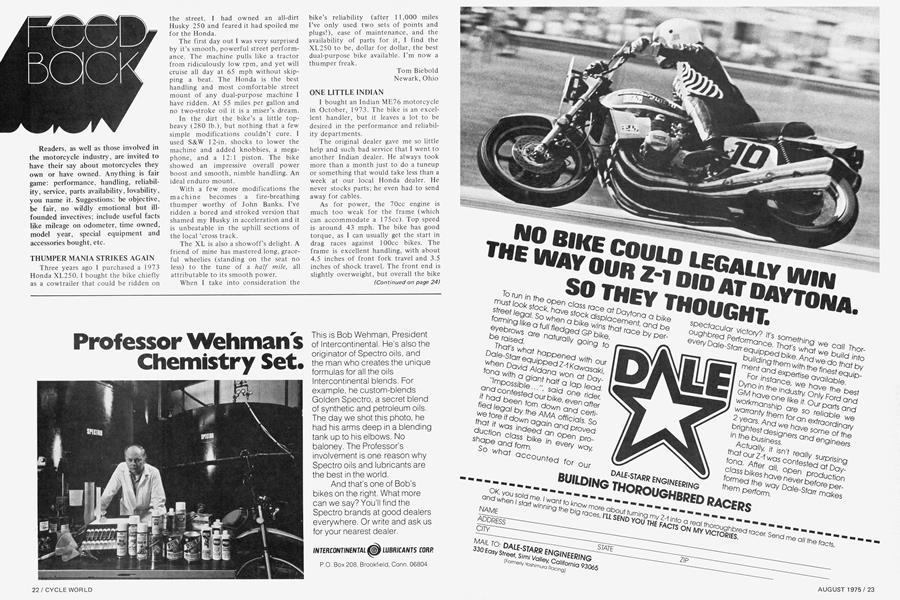

FEED BACK

Readers, as well as those involved in the motorcycle industry, are invited to have their say about motorcycles they own or have owned. Anything is fair game: performance, handling, reliability, service, parts availability, lovability, you name it. Suggestions: be objective, be fair, no wildly emotional but illfounded invectives; include useful facts like mileage on odometer, time owned, model year, special equipment and accessories bought, etc.

THUMPER MANIA STRIKES AGAIN

Three years ago I purchased a 1973 Honda XL250. I bought the bike chiefly as a cowtrailer that could be ridden on the street. I had owned an all-dirt Husky 250 and feared it had spoiled me for the Honda.

The first day out I was very surprised by it’s smooth, powerful street performance. The machine pulls like a tractor from ridiculously low rpm, and yet will cruise all day at 65 mph without skipping a beat. The Honda is the best handling and most comfortable street mount of any dual-purpose machine I have ridden. At 55 miles per gallon and no two-stroke oil it is a miser’s dream.

In the dirt the bike’s a little topheavy (280 lb.), but nothing that a few simple modifications couldn’t cure. I used S&W 12-in. shocks to lower the machine and added knobbies, a megaphone, and a 12:1 piston. The bike showed an impressive overall power boost and smooth, nimble handling. An ideal enduro mount.

With a few more modifications the machine becomes a fire-breathing thumper worthy of John Banks. I’ve ridden a bored and stroked version that shamed my Husky in acceleration and it is unbeatable in the uphill sections of the local ‘cross track.

The XL is also a showoff’s delight. A friend of mine has mastered long, graceful wheelies (standing on the seat no less) to the tune of a half mile, all attributable to its smooth power.

When I take into consideration the bike’s reliability (after 11,000 miles I’ve only used two sets of points and plugs!), ease of maintenance, and the availability of parts for it, I find the XL250 to be, dollar for dollar, the best dual-purpose bike available. I’m now a thumper freak.

Tom Biebold Newark, Ohio

ONE LITTLE INDIAN

I bought an Indian ME76 motorcycle in October, 1973. The bike is an excellent handler, but it leaves a lot to be desired in the performance and reliability departments.

The original dealer gave me so little help and such bad service that I went to another Indian dealer. He always took more than a month just to do a tuneup or something that would take less than a week at our local Honda dealer. He never stocks parts; he even had to send away for cables.

As for power, the 70cc engine is much too weak for the frame (which can accommodate a 175cc). Top speed is around 43 mph. The bike has good torque, as I can usually get the start in drag races against lOOcc bikes. The frame is excellent handling, with about 4.5 inches of front fork travel and 3.5 inches of shock travel. The front end is slightly overweight, but overall the bike weighs in at 167 pounds with a half tank of gas. The rims (steel) are heavy but strong. Shocks are no good and should be replaced. The tank is awkward and too wide. The throttle grips are the worst and should be thrown away. The seating position gives a low center of gravity and is very comfortable. Six gears are too close.

(Continued on page 24Z)

Continued from page 22

When I buy my next bike, it won’t be an Indian. I am very disappointed.

Bill Reese Middleboro, Mass.

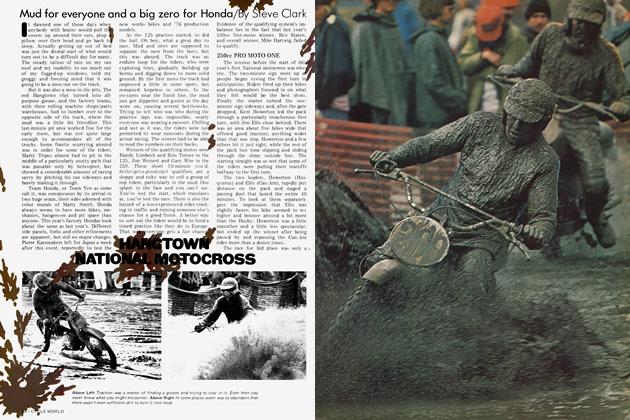

ONCE AROUND THE COUNTRY

Last summer I turned my dream of a long ride into reality, chucked everything, and went to see the country, camping out most of the time. The trip covered about 11,800 miles, basically following the perimeter of the country going counterclockwise, starting from Oakland, California. My bike is a 1972 Honda CB350, which at the start of the trip had more than 24,000 miles on it. It is fitted with short, flat Superhawk handlebars. In preparation for the trip, I rebuilt the engine, which had one broken ring, fitted the bike with a Honda 750 gas tank, and built a pair of luggage racks to go on each side of the bike.

What is it like to go on a trip that long? I was asked that by a rider friend, and I was at a loss for an answer. The best I could do was “It’s tiring.” About the only way to find out is to try it yourself.

The trip was largely uneventful, and rather than bore you with a day by day account, here is a summary of the most memorable places and events: the

mountain scenery on Route 89 up in the Sierra Nevada looking east down the valley below toward Nevada; the view of Mono Lake from a vista point by Route 395 up in the Sierras; the long lonely stretches of highway through the Mojave Desert; the searing heat of the desolate wasteland they call the Colorado Desert near the CaliforniaArizona-Mexico borders; the beautiful country in and around Big Bend National Park in Texas; the Florida Keys; magnificent Skyline Drive in Virginia; the Thousand Islands Expressway in Canada; Niagara Falls; Lake Itasca in Minnesota, the source of the Mississippi River; U.S. 2 gloriously winding through the Rockies in Montana, Idaho, and Washington; Crater Lake in Oregon, surely one of the most perfectly beautiful spots on earth.

Besides these places, there were many others, and in between, often miles and miles of unremarkable and ordinary countryside, some roads so straight and dull it was an effort to stay awake. And there were the people, practically all of whom were helpful and friendly, and the friendliest were those I met in Montana, especially Cal Bun, who runs the Phillips 66 service station in Glasgow. I spent two nights at his service station, where I replaced my broken alternator rotor. My thanks to Doug Vegge, the Honda parts man for Markle’s Hardware store in Glasgow, who went out of his way to get me the parts I needed.

(Continued on page 26)

Continued from page 24

All right, so I did have some problems with the machine. There were other problems, but not all of them can be blamed on the machine. The bike quit on me even before I got out of California, because I cut off the gas tank’s air vent by placing a big bag atop the tank and cinching it down tightly with bungie cords. Then, still in California, the two-and-a-half-year-old battery finally got so weak I couldn’t start the bike with the electric starter, so I replaced it. In Florida, my Denselube chain, with only 7000 miles on it, started stretching excessively and got stiff. I replaced it with a conventional chain, and also replaced both sprockets. The odometer quit in Rhode Island, showing 30,958 miles. The right shock went kaput in Massachusetts, where I also had a flat. It is not a good long-distance bike, because it vibrates too much, and I would have preferred a 500 or a 750, but it did get the job done, and I love it warts and all. The beauty of the bike is that it makes a good all-around machine. It does well in city riding, and it is great fun on country and mountain roads. If you are game, this 325cc machine will take you coast to coast, and from Key West to Canada.

The trip took 36 days, averaging out to 326 miles per day. The highest number of miles covered in a single day was 484. I was good for about 60 miles at a stretch, and the most I ever rode nonstop was about 100 miles. I spent $160 on gas, and I averaged 45 mpg at a constant 60 mph, carrying 60 pounds of luggage. I weigh 150 pounds in my riding outfit. I left with two new tires that lasted the whole trip. The Bridgestone tire on the rear had to be replaced shortly after I got back, and the Dunlop K81 on the front looked like it could do another 12,000 miles. K81s last me 8000 miles on the rear. I discovered during the trip how well Champion’s Gold Palladium spark plugs work.

If I were to pick the greatest impression the trip left on me, it would be the sheer size of this land. I rode hour after hour after hour, then I traced my progress on a map of the whole country and saw that I had gone only a few inches. I was awed by the size of Texas alone, where, traveling every day, I spent four days. It took five days to follow Florida’s coastline, including side trips to Key West and the Everglades National Park.

(Continued on page 28)

Continued from page 26

What was it really like? It was beautiful vistas that will fill you with reverence. It was miles and miles of dull, monotonous landscape. It was literally and figuratively a great way to get away from it all. It was discouragement at breaking down in California, practically at the start of the trip. It was the good feeling when a fellow rider from Rio Dell, a total stranger, took time off from his own vacation to offer assistance and to give encouragement, this in the middle of nowhere, in that rugged country north of Bishop, California. It was a couple of hairy moments, such as when a pickup truck pulling a trailer and boat pulled out from a stop sign right across my path. It was the satisfaction of being seen all along the East Coast with a California license plate, especially by local riders of big machines. It was the misery of riding for three straight days in steady rain and cold from Cape Cod to Canada, and for three straight days again from Michigan to North Dakota. It was the indescribable joy of riding through the Rockies in the fall on a properly loaded and goodhauling road bike. Finally, it was the satisfaction of having covered almost 12,000 miles on a relatively small machine, with only 60 pounds of luggage.

Roland Lenny Oakland, Calif.

DO-IT-YOURSELF WARNING

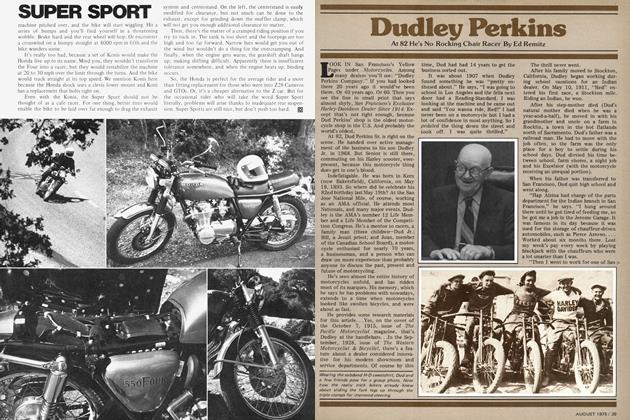

Having been an airframe and powerplant mechanic since ‘71, a diesel mechanic in the Army, and having owned three Honda motorcycles, I figured that I was qualified enough to build a custom cafe racer out of my Honda 750 Kl.

Armed with every brand of motorcycle mag, repair manuals, performance catalogs, time and money, I proceeded to start Project Aggravation II. Project Aggravation I was the rebuilding of a ‘68 Vette. Upon starting this project, I knew exactly what I wanted, a bike high in power, low in weight, reasonable in cost, and good-looking. Basically, this was followed through with Tracey Fiberglass, Yoshimura Racing equipment, Winning Performance, and Mucho Chrome. Here is where the problems lie, and I am writing this letter because I do not want anyone to go through the same problems I did. I wouldn’t wish that on my worst enemy!

These problems cannot be found in any magazine, repair manual, or The Bible. They can only be uncovered through actual work on the bike, and then you come across them too late, usually.

Problem 1. Carburetors—according to the Chilton Honda Fours repair manual: “If an acid-type carburetor cleaner is used, do not clean the float or any rubber parts in it.” Makes a lot of sense. So, after disassembling the carbs according to the manual, which means stripping them completely down, I proceeded to dump the parts into Permatex Cold Parts Cleaner, a cleaner specifically formulated for the cleaning of carburetor parts. Alas, after taking out the carb body, I discovered a whitish curly deposit in the piston bore. I checked and rechecked all of the gaskets and they were all out. So what could it be? After closer inspection with a 15x loupe and inspection light, I saw that that deposit was the nylon guide for the piston, which was now disintegrated! There is no way to take that guide out of the carb body, and besides that, it is not even illustrated as a part of the carb in the manual. Tough luck on me. I personally do not think that the guide is absolutely necessary for carb function, but that is beside the point.

Problem 2. Handling—swinging arm. According to the manual, a clearance in excess of 0.0155 is cause enough to replace the swinging arm bushings and pivot tube. Brand-new bushings and pivot tube from Honda come through with more than 0.012 in. This is after checking more than four sets of them. 1 believe that this is one of the causes of the ill-handling of the 750 Honda. Some performance buffs like me would run down to their reliable machine shop and have special bushings machined. Exactly what I did. I brought the clearance down from 0.012 in. to 0.003 in. I could have gone down even farther to maybe 0.001 in. My mistake was that 1 didn’t have the shoulder machined onto the bushing. On the stock swinging arm, there is a thing called the thrust bushing, that is made out of cheap plastic. This is the shoulder I am talking about that should have been machined as part of the bushing. Better luck for me next time!

Problem 3. Crankshaft. In my quest for more performance and reliability, I proceeded to remove the starter for less weight and also to have the alternator rotor cut down in weight from eight pounds to four. In doing so, there are a few parts that are eliminated, such as the starter, starter drive gear, reduction gear and a plate that bolts onto the rotor. With these parts removed, there is an oil hole in the crankshaft that is now exposed. This hole must be covered in order to prevent oil pressure loss and subsequent problems. All that has to be done is to machine a collar out of mild steel and place it over the hole. This is not found in any manual, magazine, or catalog. I have read performance articles on Honda 750s, and this was never mentioned.

Problem 4. An honest-to-gosh Chilton Honda Fours manual mistake. After tearing down my engine to put in the Yoshimura 812 kit, I then proceeded to follow the manual to put it all together again. I set the ring end gaps according to the manual. After assembly, I found an error in the manual, and in doing so, the engine had to come apart again. On page 83, the oil control ring end gap is measured to be 0.0004-0.0012 in. nominal. It should be 0.004-0.012 in. nominal. A mistake of one decimal point that caused me to tear apart an engine, which in turn creates a risk of breaking piston rings upon assembly. Good luck, no broken rings.

Problem 5. Yoshimura Racing. I bought the Yoshimura 750 kit, which consists of the 812 piston kit, Daytona cam, and the racing valve springs. The piston kit went in with no hitch, and the cam went in with no hitch. But, the racing valve springs were another story. The springs are of a wider outside diameter than the stock valve springs. By being wider, they do not fit in the cylinder head valve spring seat. A little machining is in order. A run down to the local Honda/Kawasaki Performance Shop places a figure of $60 on this operation. I buy the springs for $37, and putting them in costs almost double. I call Mr. Rich Goepfrich and he says that he’s sorry about my problem, and that it was supposed to be in the catalog about the machining. He did give me an answer though. He said to take a high quality hole saw of 1-3/8-in. diameter and remove the hole saw’s 1 /4-in. drill guide and replace it with a drill of comparable size to a valve stem, which turns out to be a “G” drill. This arrangement cuts through the aluminum head like butter. In fact, Ed Iskendarian recommends cutting aluminum Chevy heads the same way. The cutting tool set me back $15, but a local Honda dealer offered to buy mine, because he did not even know of the existing problem.

Because of these problems and the usual hang-ups, my bike is still in pieces. The building of a bike should be fun, entertaining, educational, rewarding, revealing, creative and satisfying. If it were not for these five problems, it would have been so. Everybody should realize that this type of project is not easy, but to dive into it without knowing certain very important facts is asking for a nervous breakdown.

(Continued on page 30)

Continued from page 29

George T. Awaliani Yonkers, N.Y.

TRIED THE LIBRARY?

I am the happy owner of a 1974 Ducati GT750. I purchased the bike last spring and am not the least bit disappointed in its performance. I also admittedly enjoy the crowd it draws wherever I park it.

The reason I’m writing is not to praise my new bike or to malign my old ‘65 BSA Lightning. I simply wish to air my frustration at trying to maintain my bike without the proper information. The owner’s manual that came with the bike is almost useless. It does a wonderful job of praising the design features of the machine, but is totally lacking in maintenance information and specifications. None of the Ducati dealers in the state have a shop manual for sale, and all claim “they’re on back order.” Well, I figured my next best bet was Clymer Publications, who at the time listed a manual for my model motorcycle. Needless to say, no one had one in stock, so it had to be ordered. After three months, having not heard from either my dealer or the local bookstore, I called Clymer long distance, and found they had canceled their plans to print that particular edition.

Getting somewhat perturbed, I wrote to Berliner Motors in New Jersey, who import Ducatis, and inquired as to where I could find a manual. After not receiving an answer, I also called them long distance and wound up talking to a rather annoyed vice president who gruffly stated, “They’re on order from Italy, and we don’t know when they’re coming,” and hung up.

Not being able to write in Italian, I cannot write to the factory. So, I’m stuck with my beautiful Bologna buzzbomb that could well be self-destructing beneath me. Can this be a conspiracy Dr. Taglioni?

Keep up the really great job you are doing. I judge a store by whether or not they carry your magazine.

Martin Dumerjich 12Î West Bloomfield, Conn.

RIDE DEFENSIVELY

View Full Issue

View Full Issue