UP FRONT

LEARNING TO RIDE: THE OPTIONS AND RISKS

Man, I can ride that bike. I’ve been driving for years." How many times have you heard that statement or, worse, even made that boast yourself? Think about it. Think long and hard because thoughts like that are opening the door for needless injury and that needless injury is convincing the general public that motorcycling, any type of motorcycling, is a hazardous proposition at best.

Convinced? No? Then consider this. When driving a car, you control speed with the right foot. On a motorcycle you control speed with the right hand. In a car, you stop by depressing a pedal with your foot. On a motorcycle, use of one foot and the right hand is required for proper braking.

What all of this means, is that in an emergency, the competent auto driver/neophite motorcyclist will make the wrong moves when he is on his bike. First, he’ll jam on the rear brake. That’s what you do in a car, right? But on a bike that will cause the rear wheel to lock and slide. And he’ll forget all about releasing the throttle and applying the front brake with his hand. Afterall, the throttle gets released automatically in a car when you go for the brake.

With the rear wheel locked, with the gas on, and with the front brake off (the front brake accounts for approximately 70 percent of a motorcycle’s stopping power under normal conditions), the best you can hope for is an unnecessary crash.

I say unnecessary, because learning how to ride before that initial assault on the highway will drastically reduce the number of injuries and fatalities involving two-wheeled vehicles. Now that you’re convinced that instruction is necessary, here are the options currently available on a mass scale and the safety risks involved with each.

First, there is the method of conning or paying a presumably competent friend for private instruction. Historically, this was the only choice available. At present, it is the method capable of training the greatest number of bikers. Instruction such as this is best accomplished off-road, far removed from traffic and the like. If your chosen instructor is a good rider, and if you spend a considerable amount of time practicing the maneuvers, you will receive sufficient training. But be advised. With this approach, you have no way of knowing whether or not your chosen instructor is skilled enough to teach! So be extremely careful!

A better introduction to motorcycling is Yamaha’s Learn To Ride Safety Program. Yamaha’s program is centered around a two-day weekend/event as they put it. Two separate areas of instruction are dealt with. First is a beginning riders’ course in which novices are taught how to start, stop, shift and turn a bike. Lectures encouraging the use of a helmet and other protective clothing are included. Since both motorcycles and helmets are furnished, a portion of the training is conducted on a bike. Approximately 150,000 individuals in 100 U.S. cities have undertaken this phase.

In addition, there is an intermediate rider safety course that covers more advanced safe riding techniques.

The instruction you get with Yamaha is good, but it is all too brief. What you are getting are the basics in a crash course, along with a lasting impression of the joys of motorcycling. So, realize that completion of this course is an excellent starting point, but it does not take you very far down a certain road called competence. Competence, you see, requires one helluva lot of practice and Yamaha doesn’t have sufficient time to practice built into their program.

At present, the most thorough approach is offered by Kawasaki. Kawasaki’s program was developed at Te^Ä| A&M University, and closely follows the Beginning Ric^r Curriculum developed by the Motorcycle Safety Foundation of Washington, D.C., from which it was adapted.

The program involves the placement of sophisticated sets of education materials in community education centers through Kawasaki dealers, and the dealers’ continuing

support of those education centers.

The “Instructor’s Kit” is the key and includes nine short films (71 minutes total), presenting the curriculum in a learner-centered format. The films are: Course Overview, Operating Controls and Devices, Identifying Important Parts, Inspecting the Motorcycle, Preparing to Ride, Riding the Motorcycle, Fundamental Motorcycle Riding Skills, Typical Riding Situations and Riding in Traffic.

Supplementing the films are Student workbooks that contain review questions and practical exercises corresponding to each film.

After the student views the film and completes the appropriate portion of the workbook, he then proceeds to a motorcycle and practices what he has learned (in front of an instructor) until he is proficient.

Also included is an instructor’s manual, a programn^p guide that takes educators step by step through the various exercises and learning areas that students will be required to undergo. The manual, incidentally, was designed specifically for use by non-professional instructors (police officers, community leaders, what have you) who have an interest in and.who are often called upon to teach classes in motorcycle safety.

As you can see, the Kawasaki approach is a very involved one, but because of that fact, and because it takes 15 to 20 hours to complete the course, graduates can learn enough to be marginal operators; and marginal operators can survive on the street!

Now, and perhaps for the first time, I hope all you prospective motorcyclists out there realize that being able to drive a car does not mean that you can drive a bike. So, seek the instruction you need when or before you buy. Not after. And while you’re at it, remember that the amount of instruction received directly relates to the level of skill attained. Enough said.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Letters

LettersLetters

JULY 1974 1974 -

Departments

DepartmentsFeedback

JULY 1974 1974 -

Departments

DepartmentsRound·up

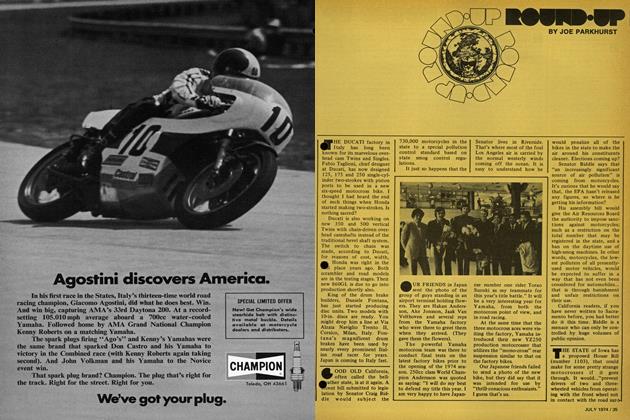

JULY 1974 1974 By Joe Parkhurst -

Fiction

Fiction"I'll Be Home In Time For Dinner."

JULY 1974 1974 By Arthur L. Frank -

Features

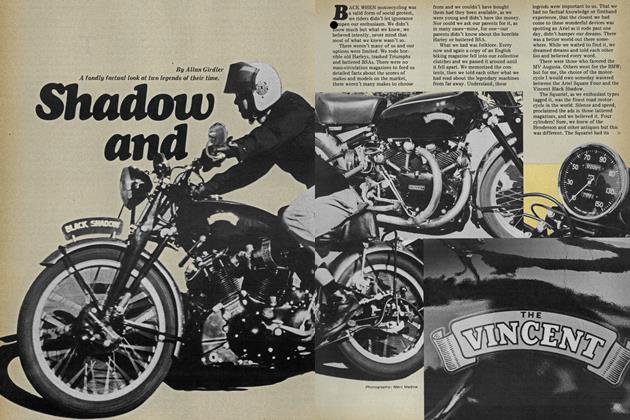

FeaturesShadow And Squariel

JULY 1974 1974 By Allan Girdler -

Special Preview

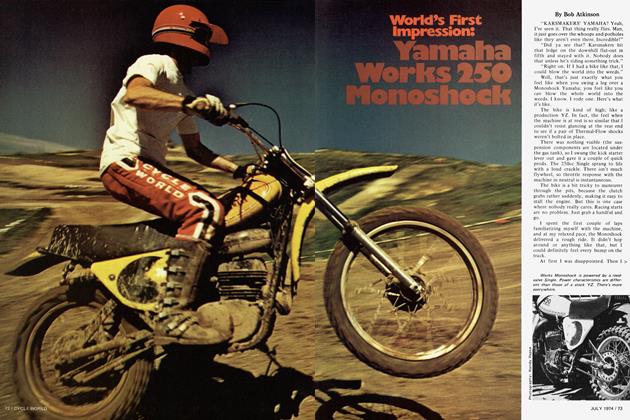

Special PreviewYamaha Works 250 Monoshock

JULY 1974 1974 By Bob Atkinson