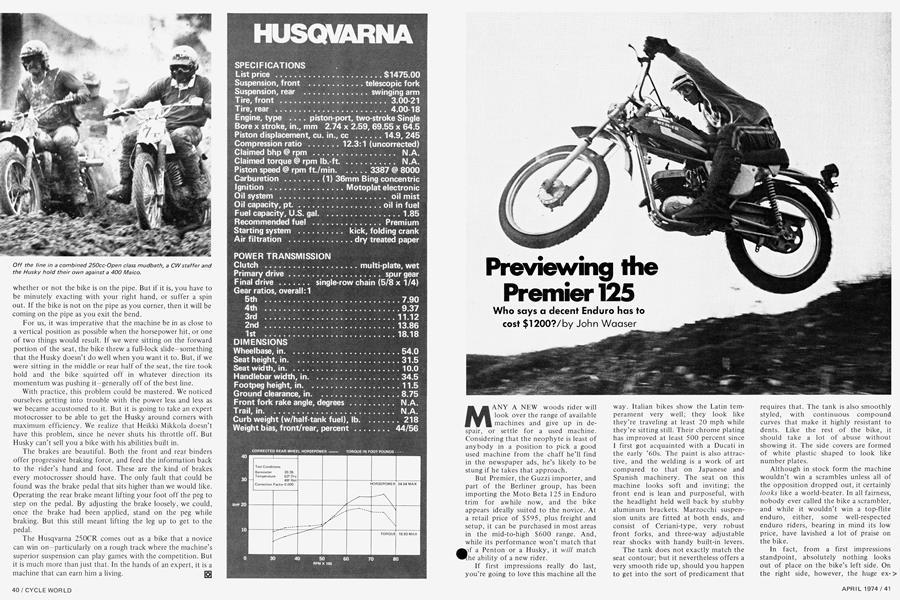

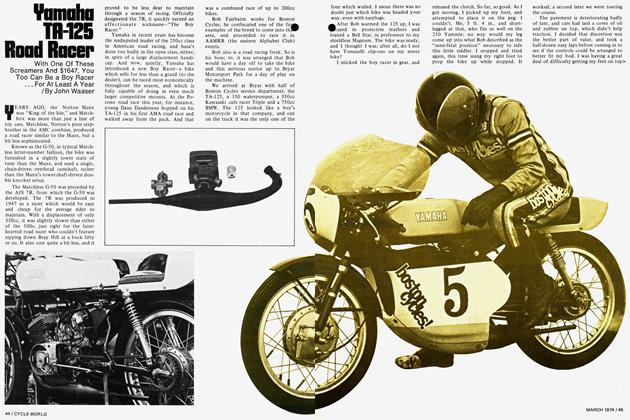

Previewing the Premier 125

Who says a decent Enduro has to cost $1200?

John Waaser

MANY A NEW woods rider will look over the range of available machines and give up in despair, or settle for a used machine. Considering that the neophyte is least of anybody in a position to pick a good used machine from the chaff he’ll find in the newspaper ads, he’s likely to be stung if he takes that approach.

But Premier, the Guzzi importer, and part of the Berliner group, has been importing the Moto Beta 125 in Enduro trim for awhile now, and the bike appears ideally suited to the novice. At a retail price of $595, plus freight and setup, it can be purchased in most areas in the mid-to-high $600 range. And, while its performance won’t match that inf a Penton or a Husky, it will match "he ability of a new rider.

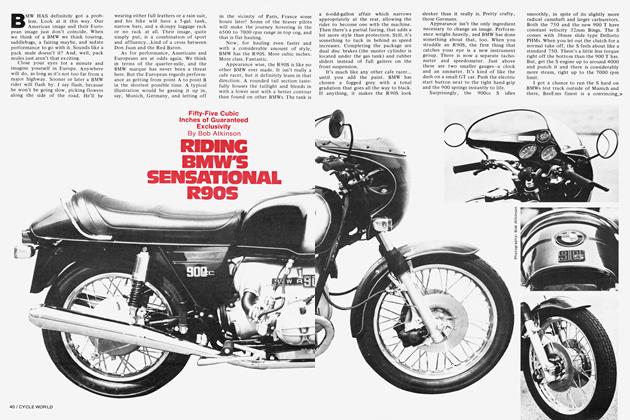

If first impressions really do last, you’re going to love this machine all the way. Italian bikes show the Latin temperament very well; they look like they’re traveling at least 20 mph while they’re sitting still. Their chrome plating has improved at least 500 percent since I first got acquainted with a Ducati in the early ’60s. The paint is also attractive, and the welding is a work of art compared to that on Japanese and Spanish machinery. The seat on this machine looks soft and inviting; the front end is lean and purposeful, with the headlight held well back by stubby aluminum brackets. Marzocchi suspension units are fitted at both ends, and consist of Ceriani-type, very robust front forks, and three-way adjustable rear shocks with handy built-in levers.

The tank does not exactly match the seat contour; but it nevertheless offers a very smooth ride up, should you happen to get into the sort of predicament that requires that. The tank is also smoothly styled, with continuous compound curves that make it highly resistant to dents. Like the rest of the bike, it should take a lot of abuse without showing it. The side covers are formed of white plastic shaped to look like number plates.

Although in stock form the machine wouldn’t win a scrambles unless all of the opposition dropped out, it certainly looks like a world-beater. In all fairness, nobody ever called the bike a scrambler, and while it wouldn’t win a top-flite enduro, either, some well-respected enduro riders, bearing in mind its low price, have lavished a lot of praise on the bike.

In fact, from a first impressions standpoint, absolutely nothing looks out of place on the bike’s left side. On the right side, however, the huge exhaust system hangs out, forcing an odd bend in the kickstart lever. Appearancewise, those are the only two things on the whole bike which look like th^ft came from Walt Disney Studios.

Going a little deeper, we find that the seat must come off in order to get at the air cleaner. Italian quick-detach seats and gas tanks are somehow never that quick, and this bike offers no exception. It also takes awhile to line things up right in order to get it back on.

The large, paper air filter sits on a plastic still-air box. That’s a neat idea, since the plastic has no seams to leak, like most fiberglass units. But the top cover, which has a slot at the bottom for breathing, simply fits over the element; thus placing the pickup about three inches below the optimum point. Remember, though, that this is no $1200 motorcycle, and it’s far better than any other bike at a comparable price.

A battery sits inside the left side cover, making the bike street-legal iÆ every state—a worthwhile consideration^ A 35-watt flywheel magneto is used, with an electronic device to rectify the current. Ignition is a conventional point/coil system. Electrics are six-volt, and the headlight is fully adequate for night riding. Handlebar controls are actually better than “typically Italian,” and feature black plastic clutch and brake levers, a neat horn button, and a dimmer switch control. The horn is as raucous as necessary on a low-speed bike.

The frame is a tubular backbone with a slight twist—the rear subframe top tubes carry forward all the way to the front frame tubes, and have heavy gusseting for additional rigidity. The excessive gusseting makes the Premier too heavy for a serious enduro bike, but, on the other hand, it’s rugged enough for anybody’s play bike. ^

Taper roller bearings are used at the steering head. The engine is shielded by a full double cradle with a light bash plate underneath. The left frame tube runs directly under the extended shifting shaft, protecting that. Overall, the impression of reliability still continues to come through strongly.

You can tell that the Premier 125 is derived from a street model, because the mounts for passenger pegs are still fitted, although the pegs themselves are not. Fenders are chrome-plated steel; the front one is mounted high. Both a chain guard and a chain guide are fitted. The rear brake is cable-operated, which helps eliminate wheel hop while using the brake on rough surfaces. Chain adjustment cams bed on sturdy bars welded to the swinging arm. A sidestand is fitted, and hangs out a bit, but nocenter stand is used.

No tool kit comes with the bike, either, but a double-end wrench, which fits the plug and the rear wheel, is snapped onto the frame just below the seat. For most owners, that should take care of most emergencies encountered away from civilization. It might be advisable to fit a few more tools, in enduro fashion, if you think you’ll need them.

Premier 125

$659

Bore and stroke are classic square 125 dimensions: 54 x 54mm. Uncor-

rected compression is 11:1. The factory lists maximum horsepower at 7500 rpm, with maximum torque at 6500. Lubrication is by oil-gas mix: oil injection is another thing you don’t get at this price.

The 125 uses the square concentric Dellorto carb—in this case a 26mm unit. Helical gears are used for the primary drive, with a Mix 5/16 in. rear drive chain, employing a cush drive, at the rear hub. A wet clutch feeds the power to a five-speed gearbox with rather wide ratios.

We picked the bike up at Westfield Auto and Cycle Sales, where a mechanic had checked it out. The first thing we noticed was that the tires seemed soft. The mechanic said that the Metzeler knobbies (2.50 x 21, front, and 3.50 x 18, rear), were made of a hard rubber compound, and that he preferred to run them soft, as that was the only way you could get any traction. These tires are better than trials universal in the woods—a good choice.

A quick walk around showed that the gas cap leaked a bit, and that one fork leg had been leaking. The bike was a much-abused demo unit. In spite of a flat battery, the machine started on the second kick, cold, and we played with it for a few minutes at the shop before 1 headed out into the woods.

It took about five minutes to work the rubber off the shift lever, compounding another problem: the lt^R was set too high for comfort, and some missed shifts resulted. The shifting mechanism was also slightly out of adjustment, and the lever was sensitive to the slightest tap from above, which would result in an immediate neutral.

(Continued on page 108)

Continued from page 43

It took less than an hour to pull the valve stem out of the rear tire, so a new tube was in order. The quick-detach rear wheel means that you don’t have to “break” the chain to change a tire. Nice. The wheel employs no rim locks; fit one if you’re really roughing it. The inside of the rim does have small knobs to grip the tire, but these are effective in direct proportion to the tire pressure. The mechanic who ran them at 8 lb. had his priorities mixed up.

I took the bike up a steep hill in third, and pronounced the engine torquey for a 125. It was torquey,Ä^ right, but just above an idle it wouiïï quit pulling, and you’d have to downshift. If you were already in first, forget it. I’d pull in the clutch to let the engine rev, then pop it again, and the front end would come up every time. Not at all inspiring. I got the feeling that this bike didn’t like to be rushed.

Next day, at Thompson Speedway, I was able to get in some laps on the oval and the road course, as well as a little dirt riding. Again the bike started on the second kick, cold, after setting in a cold fall New England rain. This in spite of the fact that the kickstarter is positioned low to avoid the pipe, and gives only one compression stroke before resulting in a painful stub of the toe. Starting is best accomplished off the bike, though it can be done from the saddle, with concentration.

That pipe was to provide anofl^P hassle on the road. With no boots, the heat comes through loud and clear. Luckily, you can position your feet to avoid the pipe while sitting down.

There was very little vibration in the detuned engine, although, oddly enough, there was one point, in the mid-range, where vibration was very annoying through the seat. Apparently

Thot pomfnrtahlp seat is hist fl little too

soft.

Top speed was clocked at 60 mph, by a Subaru coupe; though that may have just been the Soob’s top speed. “Seat of the pants” said that we were going faster on other laps. The Premier’s speedo had long since been removed. The clutch engaged way out near the end, and neutral was a bit awkward to find. Otherwise, shifting was delightful, both up and down (once adjusted).

The exhaust was very well mufflel^ due, in part, to the wide, rounded shape of the pipe, which caused so many other hassles. The more convenient, flattened pipes generally tend to resonate. Short of a huge price increase, the only way to ¡rove on the pipe location would be route it, like Suzuki does, under the engine, where it is somewhat more susceptible to damage.

Even after having to cure a sticking rear brake pedal, the brakes came as a total surprise. They are the first I’ve seen that actually seem to make the bike go faster than if you just backed off on the throttle. This is hardly typical of Italian brakes, which have always been superb. Small in diameter (4.83 in.), they are nevertheless virtually an inch wide, and should be adequate for the bike’s weight and speed. A dealer friend who can be trusted says that they’re nothing special, but fully adequate, so this demo could not have been typical in that respect. Perhaps different linings would make an improvement.

The dealer friend quotes top speed as fàser to 70 than 60, and this seemed asonable, as well. The Premier offers a comfortable cruise at 55 mph.

The following day, I went for another trail ride. The bike seemed much more comfortable when I didn’t rush it, and showed none of its earlier tendencies to stall and pull up in the front end. In fact, I was able to perform almost trials-like maneuvers, if not with consummate grace, at least with considerable alacrity.

The bike’s capabilities seem wellmatched to those of the new woods rider. Shifts could be made without the clutch, with a bit of throttle coordination, and were hampered only by that too-high shift lever. Power hardly came on with a rush, as with some woods bikes, but enough acceleration was on tap at higher rpm to throw a healthy l^pect into a novice.

^PSo we have a slow motorcycle, with a lousy exhaust pipe, and no more than adequate brakes. And sure, they could fix these things; give it more power, stretch the wheelbase, make a real competition woods mount out of it. But then it would start hard, be noisy, vibrate a lot, have a narrow, peaky power band, and cost $1200.

As it is, the Premier fills a very important void in the motorcycle marketplace. In spite of minor annoyances, it is rugged, cheap, and a lot of fun. And, while it is surprisingly good in the woods, it is also adequate on the road. It is light enough so that one man can load it into the back of an imported pickup-or pick it off of his body, if he should happen to be indiscrete enough to have to. In most cases it beats the hell out of buying somebody else’s

«rn-out pack of troubles. If there is a >d Premier dealer near you (most Ducati and Moto Guzzi dealers handle them), at least give it a look. 0

View Full Issue

View Full Issue