Vintage, Veteran And Thoroughbred Motorcyclesfor Sale In Quantity

August 1 1973 John WaaserVintage, Veteran And Thoroughbred MotorcyclesFor Sale In Quantity

John Waaser

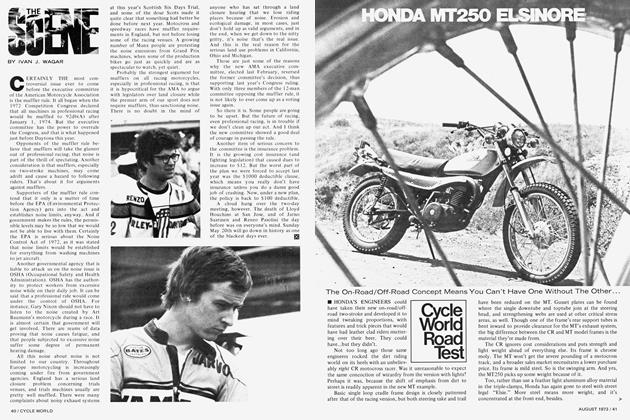

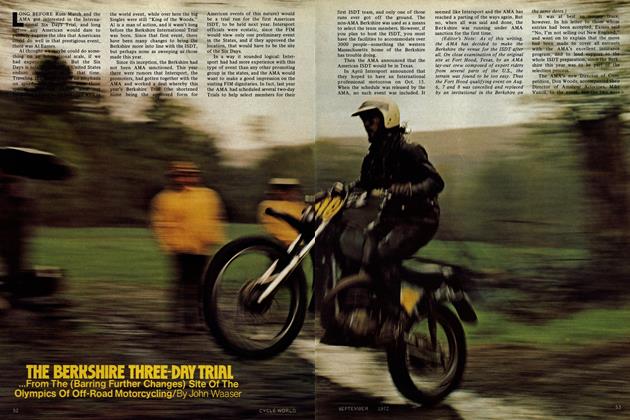

IT WAS 1946. England was just recovering from the war. When you arrived home from the service, your father promised you anything your heart desired, to show his thanks at your coming back in one piece. You chose a Scott Squirrel; a 500cc water-cooled twostroke Twin motorcycle that was steeped in tradition, yet full of some of the most amazing technology Alfred Angus Scott could unleash on the world. Now, 27 years later, you’ve moved to America, become successful, started to gray a little around the temples; and you’re waiting for your son to get back from Vietnam. What will you buy him? And you get to thinking about that Scott. Whatever happened to it? It was the machine on which you wooed your wife, and chased the magic “ton” down the narrow back roads of Britain, and by golly, you’d really like to own one like it now. Is there anywhere in this country where a man could buy a Scott like that one?

There is. David Dunfey, the errant scion of a well-known New England hotel and restaurant family, has gone into the business of importing classic British motorcycles into the United States. Condition-wise, they range from rough to superbly restored, but they are all, for the most part, complete. They range from everyday ride-to-work Royal Enfield 350s through classics like the Scott and Sunbeam, to rarities like the O.E.C., the O.K. Supreme, and a Grindley-Peerless (one of four known to remain in existence, this one’s not for sale).

David Dunfey’s personal history as a motorcyclist is almost as interesting as the motorcycles he imports. And his interest in older machines has nothing to do with personal recollections, as he is currently only 20 years old. “Two years ago, when I was a hippy,” he’ll tell you, “I started to build a chopper.” Well, the chopper never did get finished. Dave met Coburn Benson, who he refers to simply as “the Vincent Dealer” (see the Vincent supplement in the April 1971 issue of CYCLE WORLD.) The next step was reading Phil Erving’s book Motorcycle Engineering. Realizing then that choppers just weren’t the way to go, Dave went off the deep end the other way—and bought himself a Velocette Thruston. He admits candidly that Benson “influenced me a lot”—and in fact, David Dunfey is as enamored of the Vincent as any new enthusiast could be. He calls the Vincent “one of the most sensible motorcycles ever built,” and has a particular fondness for the 500cc single-cylinder Comet.

“A year ago I didn’t even know what a camshaft was,” Dave will tell you, but since then, motorcycles have become his life. He went to a local bank, borrowed a five-figure sum (the last name helped—I can see me going to the bank; “Duh, I’d like to borrow some bread to import a bunch of old English motorcycles to the United States....”) He had made contact with a man in England who specializes in buying and selling classic bikes, and flew over to make a selection. His major criterion was that the bikes be complete-and by the looks of it, the only parts which may be difficult to get will be tires for the old-style clincher rims—and Dave tells me that Japanese Rickshaw tires will fit them perfectly.

The bikes were then packed in two layers, in large shipping containers, with tires between the bikes. Nothing was removed. When they arrived stateside, he got to work cleaning them off, but did no major restoration, except under contract. “People are afraid of dirt,” he explains, which is why his Scott may be one of the more difficult items to sell; while complete, it is despicably grungy. Restoration, however, would never pay, because people simply are not willing to pay for a man’s time if he does painstaking work. Besides, Dave believes that for most of his customers, half of the joy of owning the machine would be the actual restoration of it—the pleasure of being able to say, “I did it myself.”

A couple of the machines, however, were restored in England before Dave bought them. English restorers would appear to be poor, and to have a great deal of time. As few parts are replaced as possible, and chromium is always polished, but never redone, even if it is badly pitted. Every part, however, is scrupulously cleaned, and meticulously painted and striped. So David owns a Rudge 500cc “Special” which is truly beautiful, until you look closely at the chrome, and such parts as cables, and rubber parts. Conforming with its condition is its price—the most expensive bike on his list.

Dave himself prefers a “good restoration” to an overdone, pristine machine which wants to be polished every five minutes. And most customers who got a look at his shop wouldn’t want him to restore their bikes, anyway. There is an incredible lack of sophisticated machinery-though a milling machine may be installed by the time you read this. Parts are heaped everywhere. Many tools, like his valve spring compressor, are homemade affairs which, though they perform their function admirably, are, well, crude...to put it nicely. To keep parts grouped together as they come off a bike, Dave and Dusty Wilbur, an employee, use gas station promotional glassware. It all seems most unprofessional. But they take the time to do things right—spending as much as a whole day on a magneto, for instance, the unit in question looking as if it had spent most of its life under water.

Dave is trying to stock some hard parts, also, for restorers. At present most of his parts seem to be for Vincents; that is perhaps because he spent over $600 for new parts for a Black Shadow which he is restoring for himself. He feels that Vincents are a good bet for restoration, because most of the parts are readily available. But he hopes to bring back some parts with each load of bikes, for machines which he has sold, or which he feels are popular restoration projects. And if nothing else, he hopes to encourage people to write him, informing him of parts sources, so that he can maintain a card file. Eventually he hopes to be able to help an enthusiast locate parts, even if he cannot supply them himself; to be, in other words, a sort of brokerage for restoration parts.

At present, he is also doing a lot of dealing in Harley and Indian stuff; it’s profitable, and he finds—to his dismay—that there is a ready market for the American stuff. It moves out about as fast as it comes in, while so far there has been little interest in the imported treasures; due largely to the lack of publicity. A few local ads and a trade show booth, however, have started the ball rolling.

Dave is also a sidecar freak. He maintains a stock of used sidecars, and expects to import a few used Watsonians in his trips across the pond. He is also designing a chair which he hopes to be able to manufacture, based on the lines of the Steib, which he considers the most beautiful sidecar ever. A firm in Iowa, who had already heard of these plans (possibly, Dave believes, through English sources) has inquired about marketing it for him.

Like so many who have ridden machines of every format, he is enamored of the classic British Single. Relating more modern designs to the Single, he says, “They go up and out, but not....” His arm takes over the dialogue at that point, and, finger extended, his hand moves FORWARD.

The selection of machines in his shop represents sort of an anthology of British motorcycle engineering. The bikes feature exposed flywheels, handlebar levers pivoted at their outsides, and such oddball features as a front brake operated from the rear brake rod. Many have acetylene lamps, which are now illegal except on antiques. The O.E.C. has an air-filled passenger seat, known as the Air Spring, and made by Paxon Ltd, of 70 Grafton St., Tottenham Court Rd., London IV I, and carrying patent number 253238/25. Quaint, those English addresses.... The same bike was last registered in 1941, and the acetylene headlamp still carries the black-out paint applied to all but a small circle in the center of the light.

Used motorcycles were scrapped for steel during World War II at the rate of 50 bikes per day, per scrapyard; which is why machines which were quite popular in their day have become so rare now. A few of the factories went out of production for the war, and never resumed, or never enjoyed much success, folding shortly after the war.

The most interesting bikes of all are those which use basic designs which are no longer seen. The rarest is the Grindley-Peerless, which used a sleeve-valve Barr and Stroud engine. This machine is not for sale, as Dave plans to restore it for himself. His supplier even had some misgivings about letting the machine out of England, as it is one of only four known remaining examples of this model! The Scott is a water-cooled > two-stroke Twin, with a very unusual frame design which gave a low center of gravity. The Sunbeam is an inline Twin, positioned fore-and-aft, with shaft drive. This is a late model, produced by the BSA group after the war.

The Ariel Square Four is familiar to most of us, though nobody is producing machines of this type now. There are no British V-Twins in current mass production, either, though several of the machines are of that design, a few of which use the fabled J.A.P. V-Twin engine. For that matter, there are no current British Big Bangers, of the Bold Star/ Thruxton/Fury/G-80 school, either; and virtually all of Dave’s remaining machines are the forerunners of the classic Big Single, culminating in Dave’s own Thruxton.

He has several different brands of powered wheels for bicycles, also— which you might consider the forerunner of the 50cc runabouts of today. The earliest tiddlers were engines which could be applied to a production bicycle; then came models designed as integral units—the so-called mopeds. Then came sophistication. When you realize that these little post-war bicycle engines were the start of the Honda empire—and were developed and expanded into such machines as Kriedler 50cc road racers, they take on new meaning.

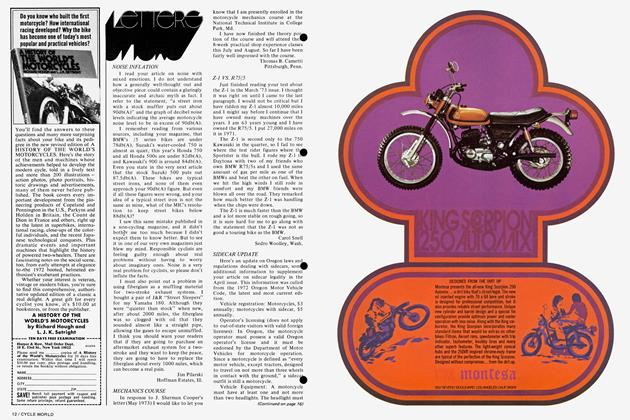

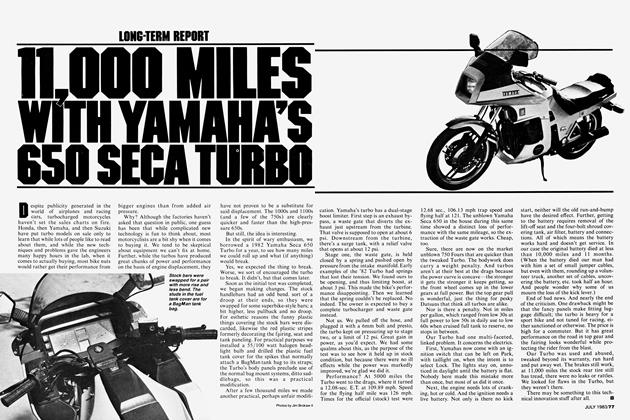

REPRESENTATIVE LIST

1922 Sunbeam V-Twin lOOOcc . .$1085

1924 Royal Enfield 350 .........655

1924 O.K. Supreme 250 .........635

1925 New Imperial 350..........535

1925 Royal Enfield 350 .........600

1925 AJS V-Twin 780cc........1000

1926 Triumph 350 .............800

1926 BSA 350.................975

1926 O.E.C. 500 ...............900

1928 BSA 493.................530

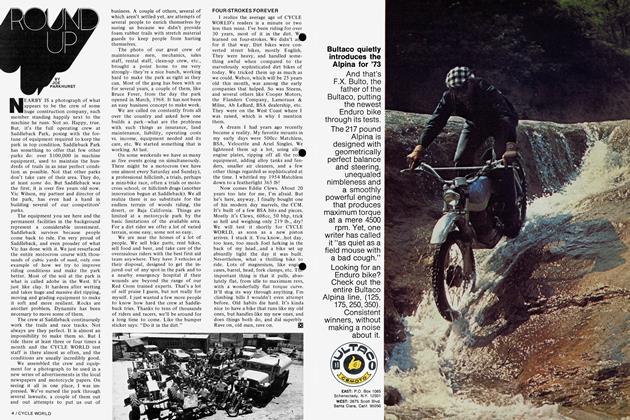

1928 Ariel 500 ................530

1934 Norton ohv 350 ...........930

1934 BSA V-Twin 880cc.........885

1937 Rudge 250 ...............655

1937 Scott Squirrel.............565

1937 AJS twin-port 350cc .......655

1948 Ariel Square Four lOOOcc . . .485

1938 Rudge Special 500 ........1685

1947 Velo cette MO V...........755

1952 Vincent Comet............585

1953 Ariel Square Four 1000 .....955

1953 Sunbeam S7..............625

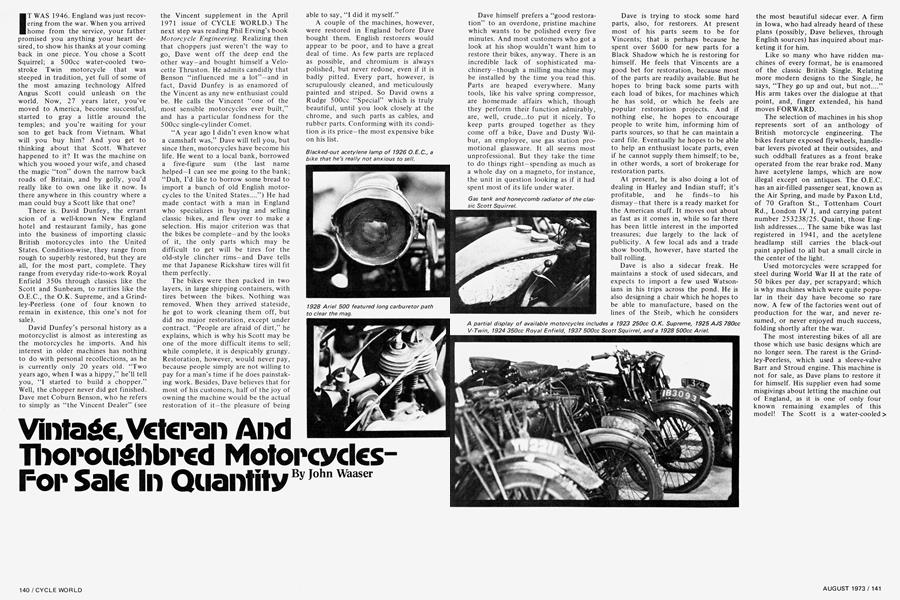

The early 1900s were a time when labor stood in for engineering. These days, flexible plastic fuel lines minimize vibration transmitted to the carburetor. Back then, fuel lines were copper. The O.E.C. fuel line has two horizontal coils laboriously formed into it, to act as sort of a spring, and cushion the vibrationcrude, but effective, and beautiful for its own sake. The beauty of labor shines through in other areas, also. Paint jobs employed meticulous hand striping, instead of those gaudy “Torino Stripes” that Kawasaki uses, or the overlapping tape stripes of the Honda.

These early motorcycles also show a great deal of experimentation in engineering. Several of them use “Intake Over Exhaust” valving—in which the intake employs a pushrod-operated overhead valve, but the exhaust uses a side valve. Several of the wheels are laced with the spokes from the brake hub going to that side of the rim, instead of the center—perhaps in an effort to better transmit the braking torque loads. The carburetors frequently have very long passages at one end or the other, to clear magnetos and such; intake tuning was a thing of the future, at least for production motorcycles.

Just a brief tour of the premises is a fascinating excursion; many small details like these abound on each machine, and Dave takes great delight in pointing them out to the enthusiast, or in hashing over possible reasons for something which he himself had not noticed before.

The Dunfey shop is located at the rear of 300 Lafayette Road, on historic route US 1, at the south end of the seacoast town of Hampton, N.H., and Dave, hippy, today-type youth in part, cannot divorce himself from some of the customs of his area and his forebears. One of these is the time-honored practice of driving home a bargain. He feels that haggling over the final price is one of the most important, and satisfying, aspects of a sale. If a man comes in and forks over the listed price for any machine, Dave will sell it to him at that price, of course, but he will feel cheated himself-robbed, if you will, of the enjoyment of determining the precise amount that a particular machine is worth to the buyer and seller both. Prices marked on the list run from $485 to $1000 for unrestored machines, and up to $1685 for the restored Rudge 500cc Special. He’ll let them go for perhaps 15-20 percent less than thatdepending on the dickering ability of the buyer, and how badly Dave wants to sell (or keep) the particular machine,

View Full Issue

View Full Issue