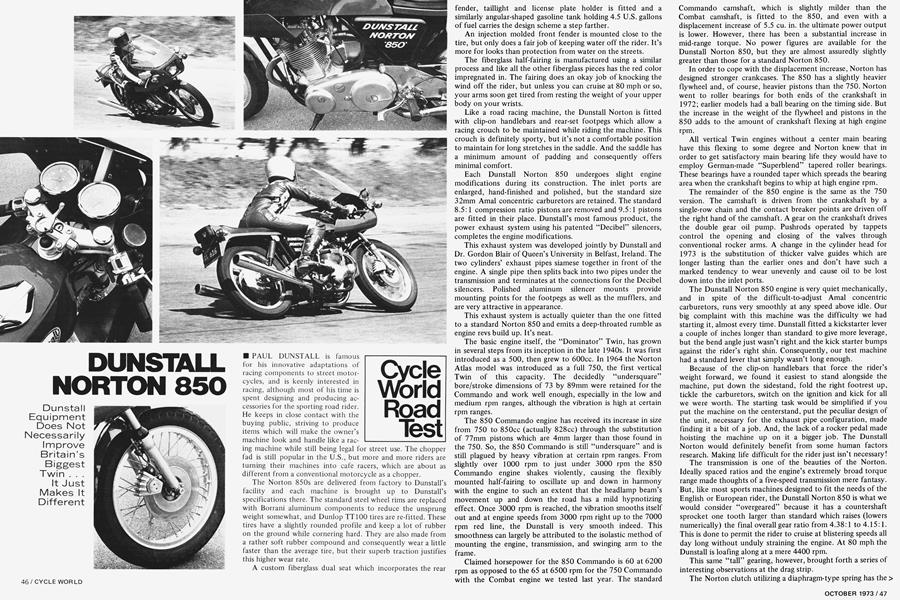

DUNSTALL NORTON 850

Cycle World Road Test

Dunstall Equipment Does Not Necessarily Improve Britain’s Biggest Twin . . . It Just Makes It Different

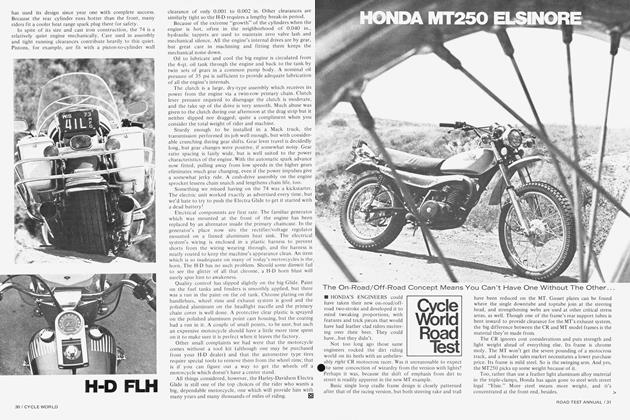

PAUL DUNSTALL is famous for his innovative adaptations of racing components to street motorcycles, and is keenly interested in racing, although most of his time is spent designing and producing accessories for the sporting road rider. He keeps in close contact with the buying public, striving to produce items which will make the owner’s machine look and handle like a rac-

ing machine while still being legal for street use. The chopper fad is still popular in the U.S., but more and more riders are turning their machines into cafe racers, which are about as different from a conventional motorcycle as a chopper.

The Norton 850s are delivered from factory to Dunstall’s facility and each machine is brought up to Dunstall’s specifications there. The standard steel wheel rims are replaced with Borrani aluminum components to reduce the unsprung weight somewhat, and Dunlop TT100 tires are re-fitted. These tires have a slightly rounded profile and keep a lot of rubber on the ground while cornering hard. They are also made from a rather soft rubber compound and consequently wear a little faster than the average tire, but their superb traction justifies this higher wear rate.

A custom fiberglass dual seat which incorporates the rear fender, taillight and license plate holder is fitted and a similarly angular-shaped gasoline tank holding 4.5 U.S. gallons of fuel carries the design scheme a step farther.

An injection molded front fender is mounted close to the tire, but only does a fair job of keeping water off the rider. It’s more for looks than protection from water on the streets.

The fiberglass half-fairing is manufactured using a similar process and like all the other fiberglass pieces has the red color impregnated in. The fairing does an okay job of knocking the wind off the rider, but unless you can cruise at 80 mph or so, your arms soon get tired from resting the weight of your upper body on your wrists.

Like a road racing machine, the Dunstall Norton is fitted with clip-on handlebars and rear-set footpegs which allow a racing crouch to be maintained while riding the machine. This crouch is definitely sporty, but it’s not a comfortable position to maintain for long stretches in the saddle. And the saddle has a minimum amount of padding and consequently offers minimal comfort.

Each Dunstall Norton 850 undergoes slight engine modifications during its construction. The inlet ports are enlarged, hand-finished and polished, but the standard size 32mm Amal concentric carburetors are retained. The standard 8.5:1 compression ratio pistons are removed and 9.5:1 pistons are fitted in their place. Dunstall’s most famous product, the power exhaust system using his patented “Decibel” silencers, completes the engine modifications.

This exhaust system was developed jointly by Dunstall and Dr. Gordon Blair of Queen’s University in Belfast, Ireland. The two cylinders’ exhaust pipes Siamese together in front of the engine. A single pipe then splits back into two pipes under the transmission and terminates at the connections for the Decibel silencers. Polished aluminum silencer mounts provide mounting points for the footpegs as well as the mufflers, and are very attractive in appearance.

This exhaust system is actually quieter than the one fitted to a standard Norton 850 and emits a deep-throated rumble as engine revs build up. It’s neat.

The basic engine itself, the “Dominator” Twin, has grown in several steps from its inception in the late 1940s. It was first introduced as a 500, then grew to 600cc. In 1964 the Norton Atlas model was introduced as a full 750, the first vertical Twin of this capacity. The decidedly “undersquare” bore/stroke dimensions of 73 by 89mm were retained for the Commando and work well enough, especially in the low and medium rpm ranges, although the vibration is high at certain rpm ranges.

The 850 Commando engine has received its increase in size from 750 to 850cc (actually 828cc) through the substitution of 77mm pistons which are 4mm larger than those found in the 750. So, the 850 Commando is still “undersquare” and is still plagued by heavy vibration at certain rpm ranges. From slightly over 1000 rpm to just under 3000 rpm the 850 Commando engine shakes violently, causing the flexibly mounted half-fairing to oscillate up and down in harmony with the engine to such an extent that the headlamp beam’s movement up and down the road has a mild hypnotizing effect. Once 3000 rpm is reached, the vibration smooths itself out and at engine speeds from 3000 rpm right up to the 7000 rpm red line, the Dunstall is very smooth indeed. This smoothness can largely be attributed to the isolastic method of mounting the engine, transmission, and swinging arm to the frame.

Claimed horsepower for the 850 Commando is 60 at 6200 rpm as opposed to the 65 at 6500 rpm for the 750 Commando with the Combat engine we tested last year. The standard Commando camshaft, which is slightly milder than the Combat camshaft, is fitted to the 850, and even with a displacement increase of 5.5 cu. in. the ultimate power output is lower. However, there has been a substantial increase in mid-range torque. No power figures are available for the Dunstall Norton 850, but they are almost assuredly slightly greater than those for a standard Norton 850.

In order to cope with the displacement increase, Norton has designed stronger crankcases. The 850 has a slightly heavier flywheel and, of course, heavier pistons than the 750. Norton went to roller bearings for both ends of the crankshaft in 1972; earlier models had a ball bearing on the timing side. But the increase in the weight of the flywheel and pistons in the 850 adds to the amount of crankshaft flexing at high engine rpm.

All vertical Twin engines without a center main bearing have this flexing to some degree and Norton knew that in order to get satisfactory main bearing life they would have to employ German-made “Superblend” tapered roller bearings. These bearings have a rounded taper which spreads the bearing area when the crankshaft begins to whip at high engine rpm.

The remainder of the 850 engine is the same as the 750 version. The camshaft is driven from the crankshaft by a single-row chain and the contact breaker points are driven off the right hand of the camshaft. A gear on the crankshaft drives the double gear oil pump. Pushrods operated by tappets control the opening and closing of the valves through conventional rocker arms. A change in the cylinder head for 1973 is the substitution of thicker valve guides which are longer lasting than the earlier ones and don’t have such a marked tendency to wear unevenly and cause oil to be lost down into the inlet ports.

The Dunstall Norton 850 engine is very quiet mechanically, and in spite of the difficult-to-adjust Amal concentric carburetors, runs very smoothly at any speed above idle. Our big complaint with this machine was the difficulty we had starting it, almost every time. Dunstall fitted a kickstarter lever a couple of inches longer than standard to give more leverage, but the bend angle just wasn’t right.and the kick starter bumps against the rider’s right shin. Consequently, our test machine had a standard lever that simply wasn’t long enough.

Because of the clip-on handlebars that force the rider’s weight forward, we found it easiest to stand alongside the machine, put down the sidestand, fold the right footrest up, tickle the carburetors, switch on the ignition and kick for all we were worth. The starting task would be simplified if you put the machine on the centerstand, put the peculiar design of the unit, necessary for the exhaust pipe configuration, made finding it a bit of a job. And, the lack of a rocker pedal made hoisting the machine up on it a bigger job. The Dunstall Norton would definitely benefit from some human factors research. Making life difficult for the rider just isn’t necessary!

The transmission is one of the beauties of the Norton. Ideally spaced ratios and the engine’s extremely broad torque range made thoughts of à five-speed transmission mere fantasy. But, like most sports machines designed to fit the needs of the English or European rider, the Dunstall Norton 850 is what we would consider “overgeared” because it has a countershaft sprocket one tooth larger than standard which raises (lowers numerically) the final overall gear ratio from 4.38:1 to 4.15:1. This is done to permit the rider to cruise at blistering speeds all day long without unduly straining the engine. At 80 mph the Dunstall is loafing along at a mere 4400 rpm.

This same “tall” gearing, however, brought forth a series of interesting observations at the drag strip.

The Norton clutch utilizing a diaphragm-type spring has the enviable reputation of being nearly unburstable. Two more plates have been added to the 850, but with the 4.15:1 gearing we were able to heat the clutch up so badly it began to slip slightly after four or five runs down the drag strip.

We made eight runs that ranged in elapsed time from 13.13 sec. to 13.39 sec. with terminal speeds ranging from 99.11 mph to 101.46 mph. Paul Dunstall was with us that day and suggested that we put a countershaft sprocket with two fewer teeth on and have another go at it. Eight runs were made with a 20-tooth countershaft sprocket which lowered the overall gear ratio to 4.56:1. These runs were not significantly different with elapsed times ranging from 13.43 to 12.99 sec. and terminal speeds ranging from 101.69 to 102.15 mph! And the sprocket change only lowered our top speed from 118 to 117 mph.

We continued our test with the 20-tooth countershaft sprocket (the clutch can cope with this gearing at the drag strip), but since all Dunstall Norton 850s will be delivered here with the 4.15:1 overall gear ratio (22-tooth countershaft sprocket), we conducted our fuel consumption tests with that gearing. The result was 49.5 mpg and that’s good in anyone’s book.

Riding a 440-lb. motorcycle with 23-in. wide clip-on handlebars can be somewhat of a job if you’re not used to that type of handlebar. It takes a good deal of strength to lay the machine over one way for a corner and then quickly right it and lean it the other way for another corner. One of our test riders remarked that, after a 100 miles or so, he could hardly sign his credit card slip at a gas station because his hands and forearms were “dead.”

Control and instrument placement on the Dunstall Norton 850 ranges from excellent to marginal. The rearset footrests necessitate having a linkage from the gear shifter shaft on the transmission to the footrest-mounted gearchange lever. This retains the familiar up-for-low shifting pattern and the shifting, either up or down, is above reproach. The rear brake pedal falls nicely under foot on the other side. The narrow handlebars could be a shade longer for a machine of this weight and the steering lock is not enough for making a U-turn in your favorite two-lane road without often winding up on the opposite curb or having to back the machine up and make another go at it.

The Lucas handlebar controls have been complained about so much that we’re getting tired of it—but here we go again. The controls consist of a blade-type lever on each side with a push-button above and one below. These are not labeled in any way and it takes a while to remember that the top button on the left hand side flashes the headlight’s high beam for passing or greeting another motorist, the left-hand blade is the headlight high/low beam control and the lower button is the horn. On the right hand side the top button does nothing, the blade switch is pushed up for signaling a right hand turn and pushed down for a left hand turn. There is a turn signal indicator on the headlight, but you can’t see it because one of the fairing braces covers it. The bottom button on the right hand side is red plastic instead of black and would appear to be a cutout button. But the one on the Dunstall wasn’t hooked up!

Braking is again one of Norton’s strong points. A handlebar mounted front brake master cylinder is acted on directly by the brake lever, which is not adjustable for point of engagement. As soon as you pull the lever the front brake begins working, so riders with small hands may have trouble getting sufficient leverage to produce really quick stops. The Lockheed front brake components are beyond reproach, however, and the braking power was fantastic—even after repeated stops from high speed there was no apparent fade.

The rear brake is a conventional two-shoe drum unit which would fade slightly after several hard applications and which squeaked throughout the test. Together, the brakes present a more than adequate system.

As was mentioned earlier, the Norton 850 vibrates more heavily than the Norton 750. Indeed, it seems as though the isolastic suspension mounts have been fitted a little more loosely on the 850 to help minimize the vibration, but as a result the handling has deteriorated somewhat. On the softest setting of the rear shock absorber springs, the machine would wallow slightly through fast bends, and raising the spring cam adjusters for a stiffer ride only helped his tendency a little. We feel that shimming up the isolastic mounts would give more precise steering, although it would mean more vibration reaching the rider.

Some points which need to be improved upon are as follows: First, the gas cap, which leaked when the tank was nearly full. Also, the fuel tank petcock dribbled fuel slightly whenever it was turned on. The placement of the rear view mirrors is a joke. You can’t see anything to the rear, although girl watching on the sidewalk on either side of the road was a snap. There should be a turn signal indicator light somewhere in plain sight. And, we’d like to see a longer kickstarter lever to make starting easier.

Still, the Dunstall Norton 850 is a unique piece of equipment. Not many will be produced so their value should equal the high asking price. The Dunstalls will be distributed by Berliner Motor Corp. in the eastern U.S. and by Norton Villers Corp. in the western U.S., the distributors for Norton and AJS motorcycles. The price has not been finalized at this writing, but by the time you read this article it will be available from the two distributors.

The Dunstall Norton 850 impressed us very much, but then we tend to like cafe racers. If you can get behind the concept, try out a Dunstall. Who knows, you might like it!

DUNSTALL

NORTON 850

View Full Issue

View Full Issue