AJS Y51 MOTOCROSSER

Cycle World Road Test

England's Big Bore Contender In The Dirt Racing Market Leaves A Fat Power Band And Good Handling As Its Calling Card.

WE TESTED the first AJS Y4 250cc motocross machine early in 1970. Certainly an impressive machine; our publisher, Joe Parkhurst, bought one for himself and has spent the past two years trying to wear it out. It's true that he doesn't ride it a great deal, but the Y4 has been very reliable and a pleasure to own.

When we took delivery of the - I new Y51 410cc motocross machine, the first person at Saddleback Park for the initial testing session was none other than Joe Parkhurst, with a covetous glimmer in his eyes. After an hour-and-a-half session, he remarked that he was going to trade his Y4 in on one!

As many of the long time riders know, the AJS name is one which has been rich in legend, but almost became extinct when the parent company, Associated Motor Cycles, went bankrupt a number of years ago. The AJS, Matchless and Norton names were very nearly lost until the people at Manganese Bronze stepped in, bought up the casting dies and manufacturing rights, and began producing AJS and Norton motorcycles once again.

It was decided to only produce one large road machine (the Norton) and a series of two-stroke competition bikes, the AJS line. In spite of some problems in England with labor and strikes, the "Nor-Vu" concern is the only really growing cycle producing company in England, a country from which many exotic and superb motorcycles have come.

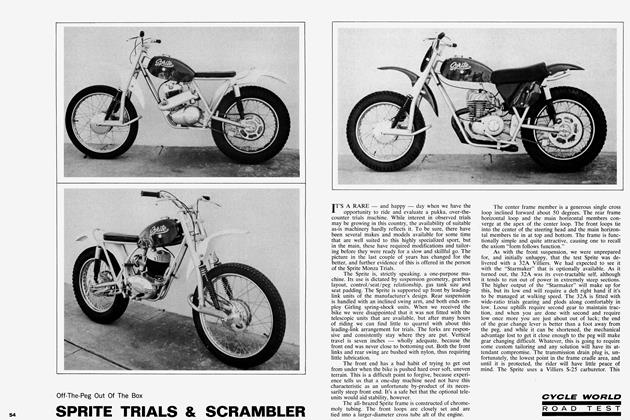

Starting almost from scratch, the AJS division has come up with one of the most pleasing motocross packages to appear recently. While some details are a little on the archaic side, others are easily modified by the owner to transform the Y5 1 into a truly oleasin~ bike.

The first criticism we had about the AJS came up when we tried to start the engine. Because the right hand side foot rest doesn't fold all the way up, it's only possible to get roughly two-thirds of the kickstarter lever travel before the lever hits the foot rest. This isn't bad if the bike is warm and not flooded, but if conditions are otherwise it's practically impossible to get the engine spinning fast enough to get it started. Grinding the foot rest stop and bending the kickstart lever outward slightly cures this and could be done at the factory.

Once started, the big AJS will potter along like a big-bore trials bike at low throttle openings, and fairly torques its way faster when the loud handle is turned open. Such tractability from a racing two-stroke is rare indeed and would lead one to think that the engine was of the "undersquare" configuration, having a 1on~er stroke than bore.

Such is not the case as the Y51 is decidedly "oversquare," sharing the 83mm bore of the Y50 (370cc motocross machine), but having a 6mm longer stroke of 74mm. The low speed pulling power reminds you of a big four-stroke Single. You know, the kind like you used to own.

I-'ower delivery is progressive and the vibration level is quite low for a machine of this design. Some big bore two-strokes we've sampled lately shook badly enough to make your eyeballs spin in their sockets after half an hour in the saddle, but not so with the AJS. Very smooth.

Such a flexible, relatively slow-revving engine makes the AJS very easy to ride, especially on dry, hard surfaces where traction is a problem. Although we felt that the standard gearing was a little on the "tall" side, lofting the front wheel to clear obstacles was relatively easy merely by blipping the throttle ooen and ent1v tu~in~ on the handlebars.

Mechanically, the engine is interesting because it's the satisfying result of a fairly old design. Most modern two strokes are of unit-construction design with the crankcase, primary case and transmission being an integral unit. The AJS retains the older style semi unit-construction design of the Villiers engine from which it was developed with the transmis sion bolted to the back of the crankcase.

There is much to be said in favor of a unit-construction engine, but most of the advantages of this design are also found in the AJS; namely, the absolute rigidity between the engine and the gearbox. And the increased number of gasket surfaces which can leak oil are still there, too!

me Dottom enu is tairly conventional. Husky roller bearings support the crankshaft and full circle flywheels are employed. These and the external flywheel surrounding the AC generator for the energy transfer ignition system add to the bike's tractability and low-speed pulling power. A steel connecting rod rides on roller bearings at the big end, but uses a plain bearing at the top. Strange, you might think, if you know that almost every two-stroke engine these days uses needle bearings there.

There is logic in using a plain bearing, however, because there is more actual bearing surface than with a needle bearing, and each rod assembly is produced only as an assembly because the rod, crankpin and crankpin roller bearing cage are all sized to each other. In a high rpm engine there could be a problem with a plain top end bearing, but not in theAJS.

An interesting note, especially to Southern Californians, is that all Y5 1 pistons are manufactured in Long Beach by Venolia!

A preemptory inspection of the crankcase discloses win dows which lower the primary compression for better torque.

Most competition oriented two-strokes still employ the tried and true petroil lubrication system. Mixing the gas and oil (at a 20: 1 ratio in the AJS) is considered an unpleasant task by many; but looking at it positively, you'll never run an oil tank dry! The gas/oil mix lubricates the connecting rod, cylinder/piston and right hand main bearing on the AJS but the drive side (left hand) main bearing receives it~'s oil from the primary chaincase oil supply.

Depending on your preferred type of riding, the Y5 1 is available in two different versions. The motocross one which we tested has a close-ratio gearbox, a rather small capacity gas tank and a superb handling frame constructed of Reynolds 531 tubing, a chrome-molydenum steel of high stress resist ance, and of quality equal to America's best racing quality alloys.

For about $60 less, you can get a Y51 with a larger ga5 tank, wide-ratio gearset and a frame constructed of mild steel for desert-type racing or just cow-trailing. We'd spend th€ extra $60 just for the 53 1 frame. If you break it, for onc thing, the material is quite amenable to brazing, which makes repair simpler.

The robust transmission follows in the typical British tradition-shifting with the right foot. The shift pattern is up for low and down for second, third and fourth. It is a direct-drive top gear unit and this precludes the primary-type kickstart mechanism allowing in-gear starts. You have to select neutral and engage the clutch before operating the kickstarter, which most of us prefer to do anyway.

The rächet and pawl gear shifting mechanism and the closeness of the internal transmission ratios aids in obtaining crisp, positive shifts, in spite of the fact that the gear lever travel is quite long. Shifting action is reminiscent of the older AMC gearboxes and missed shifts are rare.

Less well-liked was the clutch and its action. AJS has decided to stay with the all-metal clutch, which is simple and is a fairly foolproof method of transmitting the crankshaft’s torque to the transmission. However, the clutch throwout bearing is a weak design point and will fail if the clutch lever is held in for extended periods of time. In addition, the steel plates heat up and swell if allowed to become overly hot, making for clutch slip and difficult shifting.

But the AJS is a racing machine and shouldn’t be left in gear with the clutch withdrawn, anyway. If used as it was designed, the clutch, whose pressure is controlled by an automotive-type diaphragm spring, is reliable and does its job very well.

The control layout on the Y51 is much the same as any competition machine with the exception of the location of the gearshift and rear brake levers. Both these levers are comfortably positioned. The AJS one up, three down shift pattern on the right hand side is a rarity, and more English. For motocross racing, the generally accepted practice is a onedown, the remainder up shift pattern because of the difficulty in down-shifting which could arise when trying to pull up on the shift lever when traversing very bumpy ground.

Handlebars are high, wide and handsome, permitting good control over rough ground whether sitting or standing, and new aluminum clutch and brake levers are comfortable and less prone to breakage in the event of a spill.

The sitting position is one not often used in motocross, but when the need arises the seat is just wide enough for comfort and the padding is excellent—not too soft, not too firm.

Handling qualities of a racing machine are very important, and more especially if the bike is a little less powerful than some of its competition. Both apply to the AJS, as the Y51 will lose a drag race to a Husky or a Maico, but the wide power range and superb handling qualities just might make up the difference. As on earlier AJS machines, the front fork action is quite stiff, especially until the forks have had a chance to break in. The substitution of SAE 10 fork oil in place of the recommended SAE 20 helps a great deal. A generous 6/4 in. of travel is offered and the forks themselves are very robust and are cradled in a shiny pair of aluminum triple-clamps.

Rear suspension is by Girling shock absorbers which are fitted with springs of the correct poundage for the machine’s weight and an average weight rider on board. Travel is sufficient, although not overly generous, and the action is well nigh perfect.

For its intended purpose, the Y51 has very good brakes. They are small in diameter in comparison to some big bore motocross machines, but only a moderate amount of pressure is necessary to actuate them properly and machine control under heavy braking is good. However, those who tend to use the rear brake heavily may notice some tendency toward its fading. None of our staffers complained, but then we weren’t actually racing the machine either.

Akront aluminum alloy wheel rims are now standard equipment and are considered to be the strongest aluminum wheel rims available. Thick, strong spokes tie the hubs and rims together, and the rear hub now has 10 bolts for attaching the rear sprocket instead of the previous five.

Maintenance of the Y51 is aided in no small way by the inclusion of a First Aid Kit with each machine which includes spare piston rings, control cables, and other often needed parts. Packing this kit along to the races will often save grief when you need another cable. All other items which might need servicing at the race track are within easy reach, with the exception of the countershaft sprocket, which is ensconsed between the inner primary cover and the transmission shell. Changing this sprocket requires removing the clutch, which is a time-consuming process, but shouldn’t become necessary until other work is needed because of the large range of rear wheel sprockets available for changing the gear ratio.

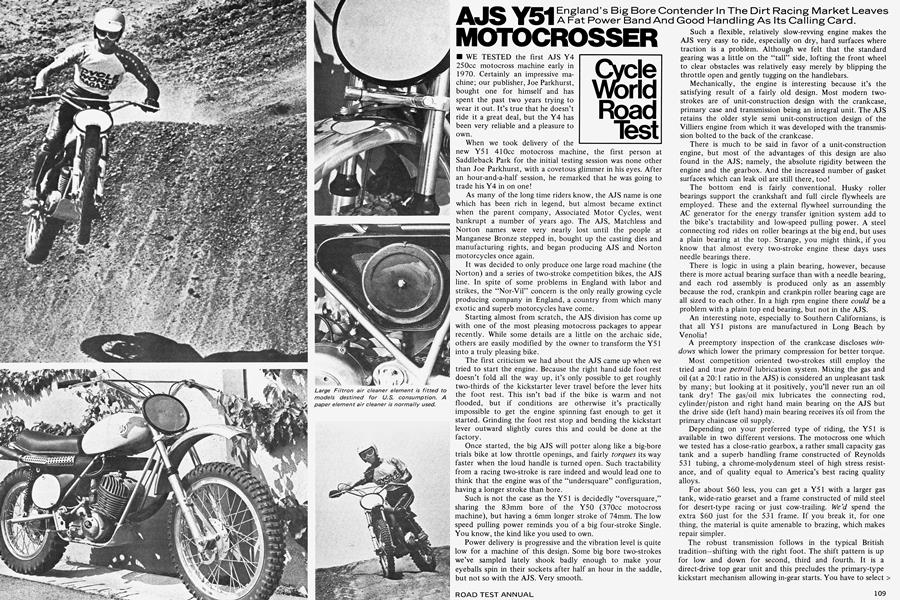

The AJS is a very businesslike looking piece of equipment with nicely styled and molded fiberglass components, one of which houses the large Filtron air filter element, and snazzy aluminum alloy fenders. Minor annoyances crop up here and there like the gas tank cap which weeps a bit, and an occasional nut or bolt which wasn’t tightened properly at the factory. But by and large, the AJS 410 is one of the most delightful big bores we’ve had the pleasure to test recently.

AJS

Y51

List price........ ............... $1375