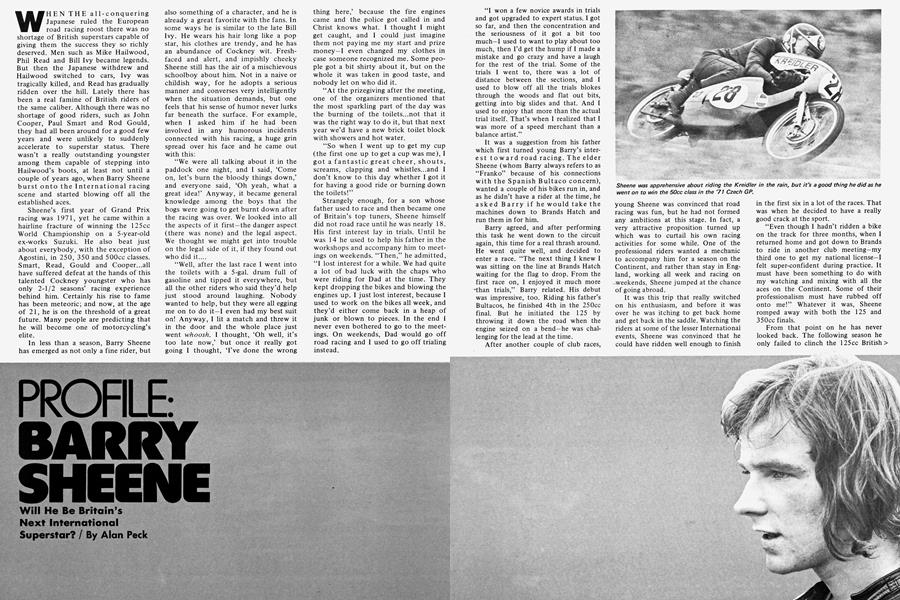

PROFILE: BARRY SHEENE

Will He Be Britain's Next International Superstar?

Alan Peck

WHEN THE all-conquering Japanese ruled the European road racing roost there was no shortage of British superstars capable of giving them the success they so richly deserved. Men such as Mike Hailwood, Phil Read and Bill Ivy became legends. But then the Japanese withdrew and Hailwood switched to cars, Ivy was tragically killed, and Read has gradually ridden over the hill. Lately there has been a real famine of British riders of the same caliber. Although there was no shortage of good riders, such as John Cooper, Paul Smart and Rod Gould, they had all been around for a good few years and were unlikely to suddenly accelerate to superstar status. There wasn’t a really outstanding youngster among them capable of stepping into Hailwood’s boots, at least not until a couple of years ago, when Barry Sheene burst onto the International racing scene and started blowing off all the established aces.

Sheene’s first year of Grand Prix racing was 1971, yet he came within a hairline fracture of winning the 125cc World Championship on a 5-year-old ex-works Suzuki. He also beat just about everybody, with the exception of Agostini, in 250, 350 and 500cc classes. Smart, Read, Gould and Cooper...all have suffered defeat at the hands of this talented Cockney youngster who has only 2-1/2 seasons’ racing experience behind him. Certainly his rise to fame has been meteoric; and now, at the age of 21, he is on the threshold of a great future. Many people are predicting that he will become one of motorcycling’s elite.

In less than a season, Barry Sheene has emerged as not only a fine rider, but

also something of a character, and he is already a great favorite with the fans. In some ways he is similar to the late Bill Ivy. He wears his hair long like a pop star, his clothes are trendy, and he has an abundance of Cockney wit. Freshfaced and alert, and impishly cheeky Sheene still has the air of a mischievous schoolboy about him. Not in a naive or childish way, for he adopts a serious manner and converses very intelligently when the situation demands, but one feels that his sense of humor never lurks far beneath the surface. For example, when I asked him if he had been involved in any humorous incidents connected with his racing, a huge grin spread over his face and he came out with this:

“We were all talking about it in the paddock one night, and I said, ‘Come on, let’s burn the bloody things down,’ and everyone said, ‘Oh yeah, what a great idea!’ Anyway, it became general knowledge among the boys that the bogs were going to get burnt down after the racing was over. We looked into all the aspects of it first—the danger aspect (there was none) and the legal aspect. We thought we might get into trouble on the legal side of it, if they found out who did it....

“Well, after the last race I went into the toilets with a 5-gal. drum full of gasoline and tipped it everywhere, but all the other riders who said they’d help just stood around laughing. Nobody wanted to help, but they were all egging me on to do it—I even had my best suit on! Anyway, I lit a match and threw it in the door and the whole place just went whoosh. I thought, ‘Oh well, it’s too late now,’ but once it really got going I thought, ‘I’ve done the wrong

thing here,’ because the fire engines came and the police got called in and Christ knows what. I thought I might get caught, and I could just imagine them not paying me my start and prize money—I even changed my clothes in case someone recognized me. Some people got a bit shirty about it, but on the whole it was taken in good taste, and nobody let on who did it.

“At the prizegiving after the meeting, one of the organizers mentioned that the most sparkling part of the day was the burning of the toilets...not that it was the right way to do it, but that next year we’d have a new brick toilet block with showers and hot water.

“So when I went up to get my cup (the first one up to get a cup was me), I got a fantastic great cheer, shouts, screams, clapping and whistles...and I don’t know to this day whether I got it for having a good ride or burning down the toilets!”

Strangely enough, for a son whose father used to race and then became one of Britain’s top tuners, Sheene himself did not road race until he was nearly 18. His first interest lay in trials. Until he was 14 he used to help his father in the workshops and accompany him to meetings on weekends. “Then,” he admitted, “I lost interest for a while. We had quite a lot of bad luck with the chaps who were riding for Dad at the time. They kept dropping the bikes and blowing the engines up. I just lost interest, because I used to work on the bikes all week, and they’d either come back in a heap of junk or blown to pieces. In the end I never even bothered to go to the meetings. On weekends, Dad would go off road racing and I used to go off trialing instead.

“I won a few novice awards in trials and got upgraded to expert status. I got so far, and then the concentration and the seriousness of it got a bit too much—I used to want to play about too much, then I’d get the hump if I made a mistake and go crazy and have a laugh for the rest of the trial. Some of the trials I went to, there was a lot of distance between the sections, and I used to blow off all the trials blokes through the woods and flat out bits, getting into big slides and that. And I used to enjoy that more than the actual trial itself. That’s when I realized that I was more of a speed merchant than a balance artist.”

It was a suggestion from his father which first turned young Barry’s interest toward road racing. The elder Sheene (whom Barry always refers to as “Franko” because of his connections with the Spanish Bultaco concern), wanted a couple of his bikes run in, and as he didn’t have a rider at the time, he asked Barry if he would take the machines down to Brands Hatch and run them in for him.

Barry agreed, and after performing this task he went down to the circuit again, this time for a real thrash around. He went quite well, and decided to enter a race. “The next thing I knew I was sitting on the line at Brands Hatch waiting for the flag to drop. From the first race on, I enjoyed it much more -than trials,” Barry related. His debut was impressive, too. Riding his father’s Bultacos, he finished 4th in the 250cc final. But he initiated the 125 by throwing it down the road when the engine seized on a bend—he was challenging for the lead at the time.

After another couple of club races, young Sheene was convinced that road racing was fun, but he had not formed any ambitions at this stage. In fact, a very attractive proposition turned up which was to curtail his own racing activities for some while. One of the professional riders wanted a mechanic to accompany him for a season on the Continent, and rather than stay in England, working all week and racing on weekends, Sheene jumped at the chance of going abroad.

It was this trip that really switched on his enthusiasm, and before it was over he was itching to get back home and get back in the saddle. Watching the riders at some of the lesser International events, Sheene was convinced that he could have ridden well enough to finish in the first six in a lot of the races. That was when he decided to have a really good crack at the sport.

“Even though I hadn’t ridden a bike on the track for three months, when I returned home and got down to Brands to ride in another club meeting—my third one to get my national license—I felt super-confident during practice. It must have been something to do with my watching and mixing with all the aces on the Continent. Some of their professionalism must have rubbed off onto me!” Whatever it was, Sheene romped away with both the 125 and 350cc finals.

From that point on he has never looked back. The following season he only failed to clinch the 125cc British > Championship by the narrowest of margins. Actually, a piece of foam rubber probably cost him the title. A small piece found its way into the carburetor induction tract, causing his retirement in the crucial round. Then the following year he won the 125 title and finished 3rd in the 250cc table, as well.

Toward the end of that season, one of the rare, almost sacred, ex-works Japanese machines came up for sale. It was a real thoroughbred-a 125cc Suzuki, with twin cylinders, rotary induction, water cooling, and fitted with a 10-speed gearbox. The Sheenes talked it over, Franko put up most of the cash, and the bike was duly purchased.

With such a competitive mount, Barry naturally wanted to try his luck in a grand prix. So he entered the last one of the season, the Spanish, on the twisting, picturesque Montjuich Park circuit in Barcelona—a real rider’s circuit. He astounded everyone by almost winning, but due to a miscalculation his Suzuki was undergeared, and he was outsped by Angel Nieto on the works Derbi. Even so, he finished 2nd.

This brilliant debut prompted him to have a serious crack at the championship in 1971. In his first grand prix of the season he finished 3rd, but luck wasn’t with him for the following two and he retired while holding 1st and 2nd places. Then he put in some tremendous performances. During the next six rounds he had three wins, two 2nds, and one 3rd, which hoisted him to the top of the table in front of Nieto, the favorite.

It seemed as if the Cockney kid was going to pull it off at his first attempt, despite strong opposition from four or five highly organized factory teams. Sheene had no support from anyone. It was a private enterprise, just him and Franko, and a 5-year-old bike that was gradually being outclassed as the season wore on. The struggle became tougher as the Derbis, Maicos and Morbidellis gradually became faster due to constant development.

Then, just two weeks before the Italian round, Sheene fell off in a minor event in Holland, breaking his wrist. A few days before the race, he asked the doctors to cut the plaster off. They refused, so he went to a specialist, and said, “If you don’t take it off for me, I’ll cut the bloody thing off myself.” The specialist replied, “Well, in that case we’d better do the sensible thing and cut it off for you, because if you do it you might cut your wrist or something.”

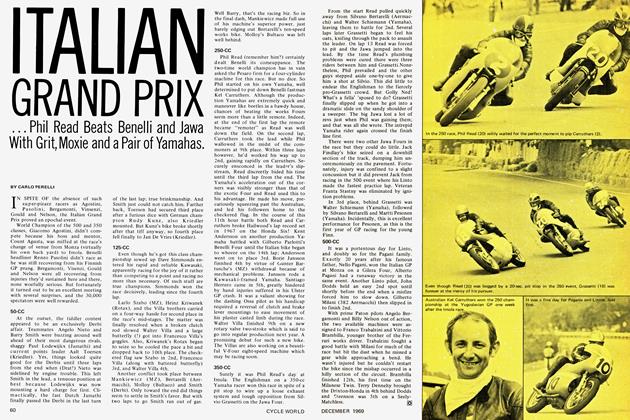

So he went to Monza and rode, although in considerable pain. It was a valiant but hopeless attempt, for the track favors the fastest machines rather than riding skill. Derbi and Morbidelli had done their homework well—the Suzuki was truly outpaced.

Not wishing to miss the Race of the Year meeting at Mallory Park in England the next weekend, Barry visited the Arsenal football team’s trainer, and had his wrist strapped up “real good.” He was in fine form at Mallory, winning the 250cc final from Read, Saarinen and Gould. In the 350, he was 3rd, and in the 500 he chased Agostini all the way home to clinch a comfortable 2nd position. Then came the big race, nearly $2500, the fattest prize in England.

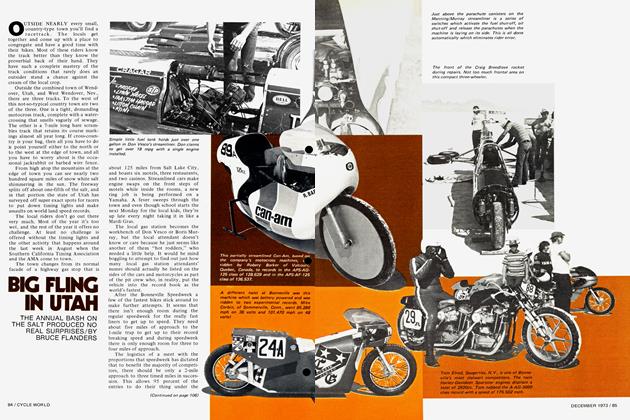

For the first few laps in that epic race, Sheene was just a few yards behind Cooper and Agostini, who were scrapping furiously. The 500cc Suzuki was no match for the MV and BSA Threes, but Sheene was wringing its neck in a game effort to stay with the faster machines in front...then it happened.

Hurtling into the notorious Gerards Bend at over 100 mph, machine and rider went their separate ways in spectacular fashion, and Barry plummeted into the banking in a shower of sparks and debris. Barry explains what hapened:

“I had some different tires on the 500, of a special compound made by Dunlop, and they were totally different than normal tires. They had a spongy sort of feel, but they obviously enabled me to go quicker, because I found I could crank the bike over a lot farther—

I could take a lot more liberties with it.

I wasn’t taking any liberties, but I was cranking the bike over a hell of a lot. I was wearing my boots out and touching the footrests and everything—but it still felt safe.

“When I went into Gerards I laid it right down and the crankcases touched the ground, which lifted the front wheel off the road and the bike just went. Trouble was, I chose the worst part to fall off, because there’s only about 25 yards run-off before you hit the banking, and you’re going faster at that point than farther around the corner. I’d only just changed down from top gear to fourth—I reckon I was doing well over 100 mph. So when I hit the deck I just stuck everything on the ground. I stuck my hands on the ground and dug my feet in and everything in an effort to slow down. But it still didn’t do any good, and I hit the bank flat out, backward;

“As it happened, I was lucky, because the whole part of my body hit the bank at the same time on impact, so I didn’t break anything—but it collapsed my lungs and I just couldn’t breath. I just didn’t have any air left in me. I thought, ‘Christ, I didn’t know being dead was like this; it’s just the same as being alive except you can’t breath!’ Anyway, I got my helmet off, but I still couldn’t breathe. It felt as if I hadn’t breathed for about three minutes! I thought, ‘If I don’t breathe soon...’ and my heart was really thumping. I remember telling myself, ‘I’ve got to breath anytime now, else I’ve had it,’ so I just heaved in a breath. After about 15 minutes I was breathing normally again, but then one of the photographers said something funny, and I laughed and half killed myself because my ribs were digging in me.”

Although Barry laughs about the incident and treats it as something of a joke, it was a terrifying and painful experience. He was taken to a hospital immediately after the race. Although nothing was broken, he was pretty well knocked about. Miraculously, his already injured wrist survived the accident with no additional damage. Later that evening he was released from the hospital.

“When I got in bed that night I felt really crooked, and I couldn’t sleep. Every time I moved I woke up again. The following two days I felt really bad so I stayed in bed. I couldn’t even stand up, let alone walk. On the third day I got up, and my legs felt like jelly, but I’d decided to go to Spain for the final Grand Prix that weekend whatever happened. I went and got an airline ticket and packed my case, then flew to Madrid the next day. When I left I felt really rough, but by the time I got to Spain I felt a lot better.”

This chapter of accidents underlines Sheene’s determination. His slight frame deceptively hides a great abundance of strength. And his mild, unassuming manner gives no indication of his remarkable guts, for there is nothing brash or visibly hard about him.

It would have been so terrific if Sheene’s game try had a fairytale ending where his lone-wolf effort was successful, and he staved off the superior challenge of the factory teams to become the youngest World Champion ever, but it was not to be. However, his fine bid ran true to form to the bitter end. While striving to match his underpowered machine with Angel Nieto’s Derbi he slid off on a slow corner, then remounted, despite losing one handlebar, and limped home to finish 3rd, while the Spaniard sped on to win the race and clinch the title. Even so, to finish runner-up in the world championship on your first attempt is a magnificent achievement, and should augur well for the future. This season the Sheenes will be concentrating on the 250cc series, and Barry will probably be riding one of the new Hi-Tac water-cooled Yamahas if forthcoming tests are satisfactory.

Of all the bikes Barry has raced, he enjoys riding the 500cc Suzuki most of all. The smallest one he’s ever ridden is the 50cc works Kreidler, and this machine was, in his opinion, the most difficult. Kreidler had asked Sheene if he would be interested in riding for them. He said he would, and an entry was made for him at the Czechoslovakian GP.

“When I went out for my first practice I hated the thing,” Barry recounted with a laugh. “I thought it was a horrible little thing. It was so small, it was so light...if someone sneezed when you went past it would have blown you off line! And I was petrified that it was going to rain because I thought that those little tires would be lethal in the wet.

“Anyway, I went out, and I was the slowest—out of everyone! I was getting into terrible problems because the gear change was all about face and everything. By the end of the session I was getting a bit more used to it. In the second practice I decided to have what I thought was a bit of a go, but it was a hell of a problem trying to tuck myself under the screen. I nearly fell off on the first lap when I tried sticking my chin on the tank. I had a bloody great Bell Star helmet on (the other 50 riders were using ‘pudding basins’ which I refuse to use), so I was trying to get my head under the screen, and it was like banging your head against a brick wall.

“When I changed gears, my knees hit my elbows, my elbows hit the tank, and the thing was going up the straight in a zig-zag. Eventually I came to the conclusion that the only way to do it was to put my head under the screen and let my knees and elbows stick out, and generally look like the villiage idiot—it must have looked pretty stupid. As it happened, it worked out all right, and in the end I thought it was quite an enjoyable little bike to ride. I managed to get the second-fastest time.

“Then, on the day of the race I looked out of my caravan window—it was pouring rain. I thought, ‘Oh, brother, I am knackered; this is going to be instant suicide.’ I was apprehensive when I went out to the line for the 50 race. The bike was so light I could have picked it up and thrown it! Anyway, the flag dropped and I got away well. The idea was for me to help Jan De Vries, Kreidler’s number one rider, but Jan broke down on the first lap, unbeknown to me. When I came around to start the second lap they hung a sign out, saying, ‘OK-GO’. I thought, ‘OKGO,’ what’n hell does that mean? They hung it out again on the next lap and I twigged that Jan must have broken down. Neito and Parlotti were in front, so I had a go and caught them. I was having a bit of a tussle and Kreidler hung the sign out again. I thought, “What do they want—blood?” I really screwed it then, and I passed Nieto. He broke down shortly afterward. I got past Parlotti and pulled out about a 150-yard lead, then he broke down as well, and I won by more than three minutes—I couldn’t believe it. Kreidler was dead chauffed—so was I.”

Talented though Sheene undoubtedly is, he fully realizes the value of his helpers, and is quick to point out that his successes are the result of good teamwork. “I’d be lost without Franko, the two Johns who mechanic for me, and the rest of the family. They all muck in and give me a hand—it’s great.” The Sheene family’s involvement in racing has spread even farther now, for Paul Smart recently married Barry’s sister, Maggie.

Barry’s hectic life leaves no room for hobbies, but he enjoys good food and is a lover of pop music. Before he turned professional he worked in a timber yard, as a car shunter at the Olyimpia car park, drove a delivery van for a store in Oxford street, and also drove a furniture removal lorry. He cut his. work down to part-time jobs as he improved at racing.

His main ambition in life at present? “Just to do as well as I can, to win as many races as possible, and the prime thing, to be really popular with the crowds through racing. That is the most rewarding part of all, to think that you may be popular, to think that some people may go just to see you race, or just to be genuinely interested in what you’re doing. It all makes it so much more worthwhile.”

One thing is certain, Barry Sheene is on the threshold of a brilliant career, and when he gets his mitts on the right machinery, Agostini and company will have to look to their laurels. |5