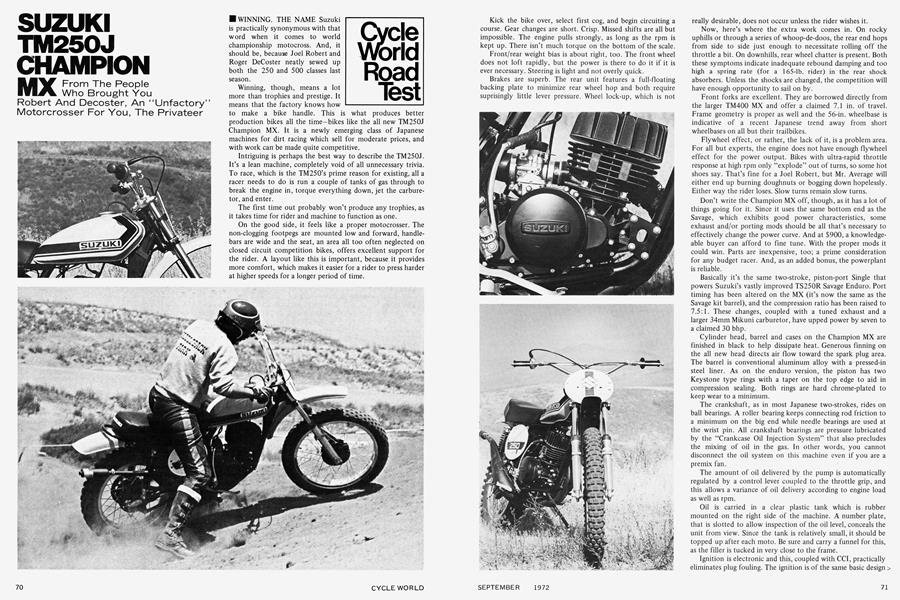

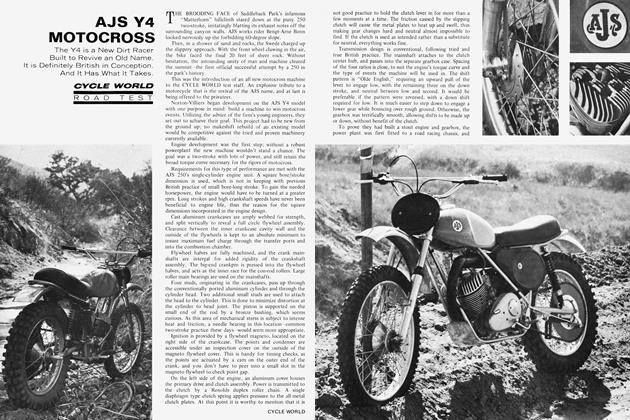

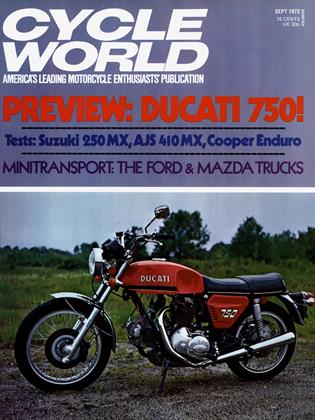

SUZUKI TM20J CHAMPION MX

Cycle World Road Test

From The People Who Brought you Robert And Decoster, An "Unfactory" Motorcrosser For You, The Privateer

WINNING. THE NAME Suzuki is practically synonymous with that word when it comes to world championship motocross. And, it should be, because Joel Robert and Roger DeCoster neatly sewed up both the 250 and 500 classes last season.

Winning, though, means a lot more than trophies and prestige. It means that the factory knows how

to make a bike handle. This is what produces better production bikes all the time—bikes like the all new TM250J Champion MX. It is a newly emerging class of Japanese machines for dirt racing which sell for moderate prices, and with work can be made quite competitive.

Intriguing is perhaps the best way to describe the TM250J. It’s a lean machine, completely void of all unnecessary trivia. To race, which is the TM250’s prime reason for existing, all a racer needs to do is run a couple of tanks of gas through to break the engine in, torque everything down, jet the carburetor, and enter.

The first time out probably won’t produce any trophies, as it takes time for rider and machine to function as one.

On the good side, it feels like a proper motocrosser. The non-clogging footpegs are mounted low and forward, handlebars are wide and the seat, an area all too often neglected on closed circuit competition bikes, offers excellent support for the rider. A layout like this is important, because it provides more comfort, which makes it easier for a rider to press harder at higher speeds for a longer period of time.

Kick the bike over, select first cog, and begin circuiting a course. Gear changes are short. Crisp. Missed shifts are all but impossible. The engine pulls strongly, as long as the rpm is kept up. There isn’t much torque on the bottom of the scale.

Front/rear weight bias is about right, too. The front wheel does not loft rapidly, but the power is there to do it if it is ever necessary. Steering is light and not overly quick.

Brakes are superb. The rear unit features a full-floating backing plate to minimize rear wheel hop and both require suprisingly little lever pressure. Wheel lock-up, which is not really desirable, does not occur unless the rider wishes it.

Now, here’s where the extra work comes in. On rocky uphills or through a series of whoop-de-doos, the rear end hops from side to side just enough to necessitate rolling off the throttle a bit. On downhills, rear wheel chatter is present. Both these symptoms indicate inadequate rebound damping and too high a spring rate (for a 165-lb. rider) in the rear shock absorbers. Unless the shocks are changed, the competition will have enough opportunity to sail on by.

Front forks are excellent. They are borrowed directly from the larger TM400 MX and offer a claimed 7.1 in. of travel. Frame geometry is proper as well and the 56-in. wheelbase is indicative of a recent Japanese trend away from short wheelbases on all but their trailbikes.

Flywheel effect, or rather, the lack of it, is a problem area. For all but experts, the engine does not have enough flywheel effect for the power output. Bikes with ultra-rapid throttle response at high rpm only “explode” out of turns, so some hot shoes say. That’s fine for a Joel Robert, but Mr. Average will either end up burning doughnuts or bogging down hopelessly. Either way the rider loses. Slow turns remain slow turns.

Don’t write the Champion MX off, though, as it has a lot of things going for it. Since it uses the same bottom end as the Savage, which exhibits good power characteristics, some exhaust and/or porting mods should be all that’s necessary to effectively change the power curve. And at $900, a knowledgeable buyer can afford to fine tune. With the proper mods it could win. Parts are inexpensive, too; a prime consideration for any budget racer. And, as an added bonus, the powerplant is reliable.

Basically it’s the same two-stroke, piston-port Single that powers Suzuki’s vastly improved TS250R Savage Enduro. Port timing has been altered on the MX (it’s now the same as the Savage kit barrel), and the compression ratio has been raised to 7.5:1. These changes, coupled with a tuned exhaust and a larger 34mm Mikuni carburetor, have upped power by seven to a claimed 30 bhp.

Cylinder head, barrel and cases on the Champion MX are finished in black to help dissipate heat. Generous finning on the all new head directs air flow toward the spark plug area. The barrel is conventional aluminum alloy with a pressed-in steel liner. As on the enduro version, the piston has two Keystone type rings with a taper on the top edge to aid in compression sealing. Both rings are hard chrome-plated to keep wear to a minimum.

The crankshaft, as in most Japanese two-strokes, rides on ball bearings. A roller bearing keeps connecting rod friction to a minimum on the big end while needle bearings are used at the wrist pin. All crankshaft bearings are pressure lubricated by the “Crankcase Oil Injection System” that also precludes the mixing of oil in the gas. In other words, you cannot disconnect the oil system on this machine even if you are a premix fan.

The amount of oil delivered by the pump is automatically regulated by a control lever coupled to the throttle grip, and this allows a variance of oil delivery according to engine load as well as rpm.

Oil is carried in a clear plastic tank which is rubber mounted on the right side of the machine. A number plate, that is slotted to allow inspection of the oil level, conceals the unit from view. Since the tank is relatively small, it should be topped up after each moto. Be sure and carry a funnel for this, as the filler is tucked in very close to the frame.

Ignition is electronic and this, coupled with CCI, practically eliminates plug fouling. The ignition is of the same basic design > as that fitted to the TM400; but because of different timing requirements, the black box, pulser, and exciter coils are different.

The system works in the following manner. A conventional rotor on the left end of the crankshaft revolves between a stator plate containing the exciter and pulser coils. The current produced by the magnet moving past the exciter coil is rectified by a diode and stored in a condenser at a potential of 200-300 volts. The charge is held by an electronic “gate” until the magnet then sweeps past the pulser coil to trigger a silicon-controlled rectifer (SCR). The SCR is an electronic version of the breaker points.

All triggering and rectifying functions are performed in a “magic black box” secured with rubber mounts under the seat. Once it is operating properly, timing will not vary. And more than 30,000 volts are available to fire a fouled plug, versus the conventional system’s 17,000 volts, a plus factor on a two-stroke.

Like the power producing half of the engine, the transmission is first class. It’s of the indirect ratio variety, which allows starting in any gear as long as the clutch is disengaged. Shifting up or down into any one of the five available speeds is quick and positive with or without the clutch.

All gears and shafts used in the transmission are identical with those found in the Savage, but the clutch is all new and incorporates a considerably beefed up housing to eliminate breakage in that area. Six driven and six drive plates resist slippage even after repeated abuse. Engagement is as smooth as anything on the market.

Primary drive, as on all Suzukis but “works” racers, is by helical gear. Both the primary and internal gearbox ratios are the same as those on the Savage Enduro; and as delivered, the bike is a little overgeared for motocross. For cross-country use, the overall ratio is about right and motocross buffs can gear down inexpensively by changing countershaft sprockets.

As indicated so far, the TM250J MX shares many components with the Savage Enduro. It also shares many cycle parts with the larger TM400 MX. The frame and swinging arm, however, are straight TM250. In order to keep things tracking as straight as possible, the wheelbase is a longish (for a motocrosser) 56 in. The benefits gained here, though, are partially negated by a high frame that still allows a full 8 in. of ground clearance under the low-mounted pipe. Crankshaft centerline, in fact, is 15.5 in. off the ground. Lowering things a bit would no doubt improve handling considerably.

The frame is liberally gusseted for added strength in two major stress areas. The first is just below the steering head on the front downtube and the other is in the area of swinging arm attachment. In keeping with the bike’s narrow lines, a single toptube and single front downtube are employed. The downtube curves beneath the engine and then joins a pair of frame members which cradle the engine, pass upward, and rejoin the toptube.

The subframe which supports the seat and rear fender, and provides the upper shock mounting points, consists of a series of triangulated tubing welded to the main frame beneath the gas tank and near the swinging arm mounting point. The swinging arm itself passes inboard of the frame tubes and is hefty enough to resist bending and flexing.

Also scoring high in the beef department are the rims and hubs. Rims are Akront. Enough said. Hubs were designed for a much more powerful machine. In fact, the wheel/hub assemblies were borrowed directly from the TM400 MX.

Most of the bolt-on stuff like the gas tank, seat and flexible fenders are also taken straight from the 400. And, like the larger MX, you either really dig the styling or wonder why Suzuki designers opted for that unusual rear fender treatment. The rear fender, incidentally, has a steel support to help prevent breakage in the event of a crash. Fender sales were big on the early 400s without the brace.

For motocross use, the low-mounted exhaust system is hard to beat because it is completely out of the rider’s way and it helps keep weight from piling up on the top of the machine. If the bike is to be cow-trailed occasionally, some sort of skid pan should be fitted to the pipe to protect it from rocks. Our test machine suffered some minor dings in the pipe during testing at Saddleback Park, which doesn’t have all that many rock ledges to hang a bike up on.

The pipe is interesting in that it does not feature a bolt-on silencer as is currently the style, but was designed with an internal baffeling system which is some 5 in. long. It is a good idea not to run this machine overly rich or load the plug up, as the baffling is not easy to get at for cleaning. To facilitate cleaning, some owners are taking the stock system out and fitting an auxiliary silencer instead. Depending on the silencer used, this modification can be better for noise pollution as well. The stock set-up is too loud for anything but competition in approved areas even though it is within the 92db limit requested by the AMA for competition machines.

As a play bike, the TM250J Suzuki is adequate as delivered. As a motocrosser, it is promising—with work. How much is up to you.

SUZUKI TM250J CHAMPION MX

$900

View Full Issue

View Full Issue