Jenny's "Poor Thing"

..And Her Brother Rode a Maypole.

Jimmie Long

I WAS TWO weeks out of the stage where riding a two-stroke on the dirt is supposed to give you warts when I learned something from Jenny Kreuger. I should have seen it coming, but I didn't know too much about motorcycling, and everybody has 20/20 hindsight.

For those two weeks I had been trying to get a girl, any girl, to go trail riding with me on that beautiful, yellow Kawasaki 175E that had swallowed all the money and then some from my graduation. There was room for two if you sat really close, which to my way of thinking was exactly the idea.

The trouble was finding the girl. The big ones didn’t begin to fit. The small, long-haired, luscious ones that I really wanted to take all seemed to have the same answer: “You won’t catch me on one of those things. My cousin Furd almost got run over by a Mack truck that way.”

Sure enough, but a Mack truck isn’t likely to jump out of the woods onto the trail and zap you like it might on a highway. If it does then you know it was your time anyway. Unfortunately, such sound logic does not prevail with such emotional creatures.

I had just exhausted this argument on a lovely little wench named Stillson, which I thought was hilarious but never mentioned, when Jenny tapped me on the shoulder.

“I vould luf to go mit you,” she said. Let me explain that Jenny Krueger was a German, very much a German, who had then been in the states only about two years. When I think of “The German Woman,” my imagination conjures visions of huge, rawboned killers carrying 6-ft. swords for toothpicks. Jenny was five-eight or so, but only about a 115 well-done pounds—a great looker with a good mind, but impossible to talk to unless you spoke German.

“I vill go motorbike riding mit you,” she repeated. She wasn’t offering or asking; she was telling.

“You vill? I mean, you will?” It wouldn’t be too bad if she sat close like I had planned and maybe keep her mouth shut.

“Sure. Mine bruder had a motorbike in Germany. He took me for rides. I vould luf to go again.”

“Well,” I stammered. “I guess it’s a date.”

“Ven vill we go?”

“Is Sunday morning okay?”

“Sure. I’ll ask mine fater. Then we go.” Him she asks, but me she tells.

When I pulled up in front of her house, the first thing I saw was Herr Kreuger standing on the porch with his arms folded and his German showing. I was terror stricken until I saw Jenny step out the door, peck him on the cheek, and skip down the steps. Herr Kreuger followed her ominously enough to make me hop out of the car and look for likely places to hide. Jenny stood by the trailer and didn’t say a word until Herr Kreuger had given me and the bike the onceor twice-over.

“Later,” she said, “This is Gary Thorn. Gary, mine fater.”

Herr Kreuger stared at me a moment, then nodded politely to acknowledge my dubious status as his guest. I didn’t offer to shake because I was afraid he would bite my hand.

“This is your motorcycle.” A flat statement.

“Yessir.”

“You intend to take my daughter riding on it?”

“Yessir.” I had hoped to. By now a somewhat dim hope.

He nodded curtly, studying the bike as if he could see through the metal to my not quite expertise in its handling.

“This bulge here seems to house the carburetor. Is it not in an unusual position?”

“Rotary valve. They say the carb has to be there.”

“Ah...Kawasaki is a Japanese brand?”

“Yessir.”

His eyebrows raised a thoughtful notch. After all, he was a German. After five minutes looking at me and ten minutes playing and poking at the bike, he turned on his heels and started for the house.

“You may go, Jennifer,” he said as an afterthought.

Jenny flashed a quick smile to balm my shaking body and went after her father into the house. She came out a minute later with a pair of small boots and a white helmet.

“That your helmet?” I asked, thinking about the $22 I had spent for a spare bucket.

“It is mine,” she said. “I vunce had a motorbike, too. Later made me wear a helmet. This one.”

We got into the car and started the haul for the boonies. At least there was common ground to talk about, although talking with Jenny was tedious at best.

“So you had a motorcycle,” I said. “What kind was it?”

“It vas a poor ting,” she said, staring intently out the window at the passing scenery.

“No, I mean what type was it? Not how good it was.”

She cocked her head a bit to the side and looked at me like I was made of brass. “Poor ting,” she stated flatly and conclusively.

I was willing to let it go at that. Trying a different tact, I asked what kind of bike her brother had.

“Oh. He has it still.”

“Okay. What kind does he still have?”

“A maypole.”

The scenery was nice from my side of the car, too, so I shut up and drove. So her brother had a maypole. I could just see it with the ribbons and everything sitting beside her poor thing.

Jenny broke the silence with a thunderclap sneeze. It must’ve opened something in her head because she started talking between sniffles.

“Mine bruder broke the swingset on his bike.”

“Swingset?” I felt something really stupid coming.

“Swingset . . . attaches the rear wheel mit the frame.”

“You mean swinging arm?” I had to search for the word.

“Ja. That’s what I said.”

“Oh.”

We settled down to a studied silence.

I felt like it was going to be a really hokey day.

We stopped on the side of the road about a mile from Jacob’s City, a town of no great distinction other than several hundred miles of trails in the area and four motorcycle dealerships inside the city limits. That worked out to one dealer for every fifty citizens. The place made its living on weekends full of motorcycles, a good deal all around.

We had stopped near five or six trailers, but no bodies seemed to be about. I could always count on people being gone when I needed them to help me unload my bike. While I was staring at the woods Jenny had already loosened the tiedowns and was sitting on the bike.

“I vill roll it off. You catch me.”

She did and I did. Probably something else her brother taught her.

It turned out to be a good afternoon. Jenny was an excellent riding partner, inasmuch as I knew how to judge such things. She sat close and tight, kept her mouth shut, and didn’t criticize when I ran into a tree and dumped us both. We spent two hours puttering slowly through the woods, just enjoying the whole thing. When we came to one of those places like you see in the Toyota commercials with the sunlight filtering through the leaves and the trees still green and pretty like they should be, Jenny would make me stop. She’d lean back with her hands on the luggage rack, smile to herself and laugh with her eyes. She never said a word, but she enjoyed it. I could tell.

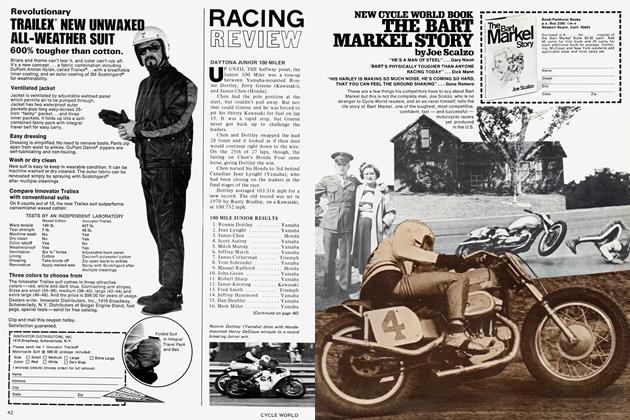

When we finally made our roundabout way back to the car, Mike Williams was there waiting for us, gulping at a bottle of my Gatorade and lounging on the Montesa, I think it was, he had leaning against the trailer. He waved the bottle at us and grinned. The dirt on his face was split by lines of white when he settled back to his normal indifferent expression. Mike did a lot of motocross in those days and rode seriously wherever he happened to be. He never won anything, but he was competing all the time. Even then that meant something to me. What’s more, he didn’t care much for tall blondes like Jenny. We made small talk until he noticed her eyeing the Montesa.

“You like?” he asked.

She looked at him quickly and nodded.

“Sit on it and see how it feels.”

She backed the bike away from the trailer and hesitantly lifted her leg over the saddle, looking at Mike like he was about to change his mind and tell her to get off. She slowly settled down, gently rocking the bike back and forth. Looking at the rear shocks, she bounced a couple of times then demurely put her hands on the gas cap and smiled.

“It is beautiful,” she stated.

Mike swigged at the Gatorade and burped. “You look like you want to ride it. Know how?”

“Ja. I had a motorbike of mine own vunce.”

“Really? What kind?”

“It vas a poor ting.”

I had wondered what Mike would do if and when she said that, but he just scratched the back of his head and smiled knowingly. If Mike could handle poor things, maypoles, swingsets, or whatever else Jenny came up with, then I supposed I could live with it, too.

“You want me to start it for you?” Mike asked.

“Please. Mine foot hurts.” Because I ran into a tree.

Smiling at me while Mike prodded at the kickstarter, she fastened her helmet and tightened her belt. She carefully clicked the bike into first and puttered away across the red sand and clay, as happy as anyone could possibly be in first gear.

“She’s a funny girl,” I said. “She used to own a ‘poor ting’ (I laughed) and, get this, her brother rides a maypole. ”

I was laughing pretty good, but Mike was giving me one of those Ha-Ha-YouIdiot sort of chuckles.

“And her old man took a real interest in your bike when you picked her up. Right?”

“Yeah. How did you know?”

“Watch.”

Jenny finally puttered back, still wearing that almost permanent grin. She started to get off, but Mike stopped her.

“Why don’t you get on it like for real,” he said. “I don’t mind.”

She stared at him a moment, shrugged her shoulders, then settled back on the saddle. Perfectly still for five seconds, she cracked the throttle and popped the clutch, showering my car and my body with sand and goop. There was a steep dropoff twenty yards away. She didn’t begin to reach for a brake, just blipped the throttle on the flying bike and soared out toward the downslope. Two minutes later the Montesa screamed up the same slope and into the air. Jenny crossed her forks to full lock and didn’t straighten out until a fraction before the rear wheel touched. By the time I had regained the tension in my slack jaw she flew by the car and into the woods.

“My God,” I muttered. “How did that happen?”

Mike started chuckling again. “That’s Jenny Kreuger, you idiot.”

“Right. So what?”

“Her brother is Tommie Kreuger, the guy that’s been eating everybody’s lunch on a 250 Maico, not maypole. And her old man drove a sidehack from Agheila to Alamein and back for the Thirty-Third Recce Unit. Ever hear of Der Afrika Korps? Back in the Big One?”

“Yeah?”

“Yeah,” he said as he poked me in the ribs. “And her ‘poor ting’.” He leaned close to my ear and whispered, “I think she was trying to say Pursang. Ever hear of that one? I’m sure you noticed she has a little problem with the language.”

“I noticed.”

“Well, old shoe, didn’t do you much good did it? I bet you really impressed her out there.”

Nice guy and all, Mike still had the tact of a wet mop.

Jenny came out of the woods a bit slower than she went in, but still faster than I had ever dreamed of going except maybe if dropped from an airplane. She handed the bike over to Mike and thanked him in profuse German, the only words she could get out fast enough.

Mike told her she was welcome, smiled at her, smirked ridiculously at me, and rode off. What could I do but wave bye-bye?

“It vas fun,” Jenny said.

I stared at her, so mad that I could barely get the words to come. “Why didn’t you tell me you could ride like that? I made a fool of myself, making a big deal of fifteen miles an hour, running into trees, and generally appearing like a complete idiot. All you had to do was tell me and I wouldn’t have bothered.”

Jenny’s bright eyes quickly faded. Her eyelids dropped. When she looked up at me they were glistening with tears. It’s a trick they teach girls in their gym classes; it has to be, because they all can do it.

“That is why I did not tell you. I said I vould go trail riding mit you and I did. I did not want to race because I cannot laugh when I race. When I race I do not see a tree ... I see someting not to hit. It is good to go slowly and have fun. I did. It should be important to you because it is to me.”

I started to say something, but Jenny still had her mouth open. She had stopped crying.

“Gary, your Sawasaki is so much better to ride on the back than mine bruder’s maypole. There is a better place to sit.”

She paused to study my face. “Put gas in the tank and we go again. Okay?”

This time she was asking. It felt kind of good.

“Okay,” I said. “We go again.” CÖ]