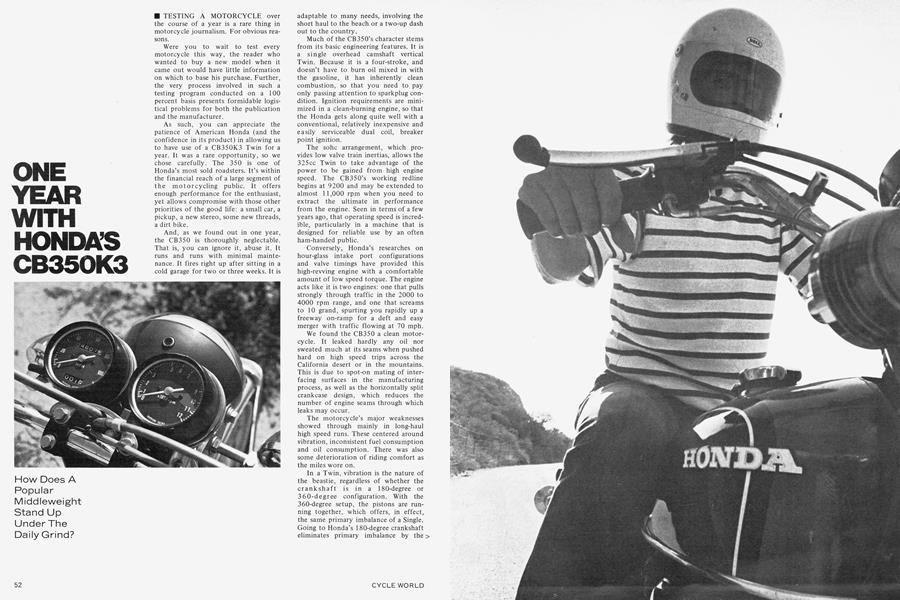

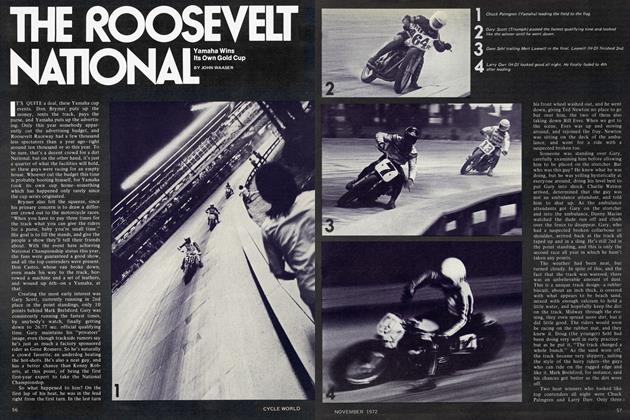

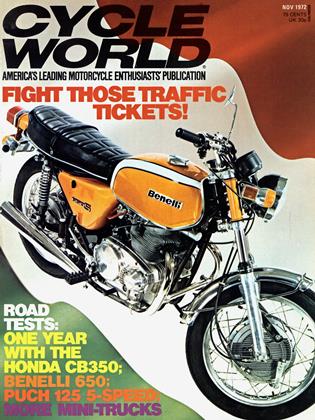

ONE YEAR WITH HONDA'S CB350K3

How Does A Popular Middleweight Stand Up Under The Daily Grind?

TESTING A MOTORCYCLE over the course of a year is a rare thing in motorcycle journalism. For obvious reasons.

Were you to wait to test every motorcycle this way, the reader who wanted to buy a new model when it came out would have little information on which to base his purchase. Further, the very process involved in such a testing program conducted on a 100 percent basis presents formidable logistical problems for both the publication and the manufacturer.

As such, you can appreciate the patience of American Honda (and the confidence in its product) in allowing us to have use of a CB350K3 Twin for a year. It was a rare opportunity, so we chose carefully. The 350 is one of Honda’s most sold roadsters. It’s within the financial reach of a large segment of the motorcycling public. It offers enough performance for the enthusiast, yet allows compromise with those other priorities of the good life: a small car, a pickup, a new stereo, some new threads, a dirt bike.

And, as we found out in one year, the CB350 is thoroughly neglectable. That is, you can ignore it, abuse it. It runs and runs with minimal maintenance. It fires right up after sitting in a cold garage for two or three weeks. It is adaptable to many needs, involving the short haul to the beach or a two-up dash out to the country.

Much of the CB350’s character stems from its basic engineering features. It is a single overhead camshaft vertical Twin. Because it is a four-stroke, and doesn’t have to burn oil mixed in with the gasoline, it has inherently clean combustion, so that you need to pay only passing attention to sparkplug condition. Ignition requirements are minimized in a clean-burning engine, so that the Honda gets along quite well with a conventional, relatively inexpensive and easily serviceable dual coil, breaker point ignition.

The sohc arrangement, which provides low valve train inertias, allows the 325cc Twin to take advantage of the power to be gained from high engine speed. The CB350’s working redline begins at 9200 and may be extended to almost 11,000 rpm when you need to extract the ultimate in performance from the engine. Seen in terms of a few years ago, that operating speed is incredible, particularly in a machine that is designed for reliable use by an often ham-handed public.

Conversely, Honda’s researches on hour-glass intake port configurations and valve timings have provided this high-revving engine with a comfortable amount of low speed torque. The engine acts like it is two engines: one that pulls strongly through traffic in the 2000 to 4000 rpm range, and one that screams to 10 grand, spurting you rapidly up a freeway on-ramp for a deft and easy merger with traffic flowing at 70 mph.

We found the CB350 a clean motorcycle. It leaked hardly any oil nor sweated much at its seams when pushed hard on high speed trips across the California desert or in the mountains. This is due to spot-on mating of interfacing surfaces in the manufacturing process, as well as the horizontally split crankcase design, which reduces the number of engine seams through which leaks may occur.

The motorcycle’s major weaknesses showed through mainly in long-haul high speed runs. These centered around vibration, inconsistent fuel consumption and oil consumption. There was also some deterioration of riding comfort as the miles wore on.

In a Twin, vibration is the nature of the beastie, regardless of whether the crankshaft is in a 180-degree or 3 60-degree configuration. With the 360-degree setup, the pistons are running together, which offers, in effect, the same primary imbalance of a Single. Going to Honda’s 180-degree crankshaft eliminates primary imbalance by the > self-canceling effect of opposite moving pistons, but at the same time introduces a rocking couple.

That couple may or not be the source of disturbing vibration, depending on how far the pistons are from one another, the engine speed, and the degree to which that vibration resonates in the frame. In the CB350’s case, the rocking couple imbalance makes itself felt at freeway speeds, yet is hardly noticeable when engine speed is changing frequently, as in town travel or riding through curving country road.

Due to this tingling vibration, we would not seriously entertain the thought of taking the CB on a tour of the states, as constant speeds between 55 and 75 mph entail too much punishment. Passenger peg vibration at these speeds is particularly severe. This should not detract from the bike’s main purpose as a machine of occasional sport.

Gasoline consumption on fast hauls was a great disappointment and illustrates the basic plight of small bore engines in general. Run them hard and economy disappears. Normally, you expect to get the least favorable mileage figures in town, due to the fact that you are constantly starting, stopping and idling.

The CB350 exhibited tendencies contrary to this, particularly when pushed along above 60 mph for any great length. The bike gets about 50 mpg in town, but drops to from 20 to 35 mpg on the highways. The worst figure—20 mpg—was recorded on a trip fighting a desert headwind for 60 miles.

The carburetion is also easily affected by altitude changes. The richer mixtures cause occasional misfiring above 3000 feet or so, especially under load. The miss occurs below 7000 rpm and disappears above that engine speed. Oil consumption is quite high at one quart per 600 miles. Part of the reason must be the rather rowdy break-in it received during its initial road test. This figure seems inconsistent with the results we have had with other Honda Twins, normally a very frugal type of engine.

In the comfort department, the ride has suffered in direct proportion with the deterioration of damping in the rear shock absorbers. When you hit a bump with an undamped rear wheel, the frame rebounds suddenly as the springs fight compression. The result is hard on your seat and kidneys, and also makes the stability of the machine less certain in rough turns. Honda rear dampers have never set a standard in the motorcycle industry and these are no exception, having retained their efficiency for only a few thousand miles.

In terms of mechanical malaise of the sort that leaves you high and dry, or lonely and wet, the Honda was almost perfect. The seat base is cracking from weight and vibration, and thus the saddle has become overly flexible in the middle. We’ve left it be. At the 4000-mile mark the gasoline cap quick release mechanism broke, presumably from vibration. It was repaired for $4.73, parts and labor.

Before we took the CB350 to the drag strip for its second crack at the performance runs, we delivered it to a local Honda dealership for a complete service, which cost $38.65. This included labor and parts for a tune-up involving changing plugs, checking timing, adjusting carburetors, valve clearances, as well as the above mentioned gas cap repair, oil change and replacement for a worn throttle cable.

We kept tabs on the cost for fuel and oil during the 2000 to 4000 mile interval: it came to $18.47. This included an oil change (by us) every 1000 miles.

The present condition of the bike at 4500 miles may be summarized as clean, and mechanically good with a few minor faults. There is a first-gear clunk when the clutch is released, having to do with wear in the shock absorbing cushion in the power train. Gear whine has become noticeable in 5th gear when the engine is hot, and the feel you get back when you downshift is somewhat vague at high temperature, too, indicating a future need for some minor transmission and clutch adjustment. The clutch itself is still strong and solid.

Comparison of performance figures taken in new and used conditions yielded the foreseen results, with a surprise or two. Quarter-mile performance and top speed dropped somewhat, which is to be expected. However, braking performance improved considerably with a 60 to zero mph stop that was more than 12 feet better than in the initial test. The first stopping distance was exemplary, but the second was downright terrific.

Such is the story of a muchneglected, hard-pushed machine. One that barely breathed hard in an uphill run from Indio to Blythe in 112 degree F desert temperature at 70 to 80 mph. One that fired up easy as a charm when we wanted to run down to the Tic Toe for some cigs. One that was inherently light handling and stable for a dash up our favorite canyon, in spite of poor damping. One that toted us and our cutie to Saddleback for a summer motocross.

In its proper role, the CB350 is a hard motorcycle to beat, judged in terms of its price, performance and reliability.

CB350K3

$18.47

View Full Issue

View Full Issue