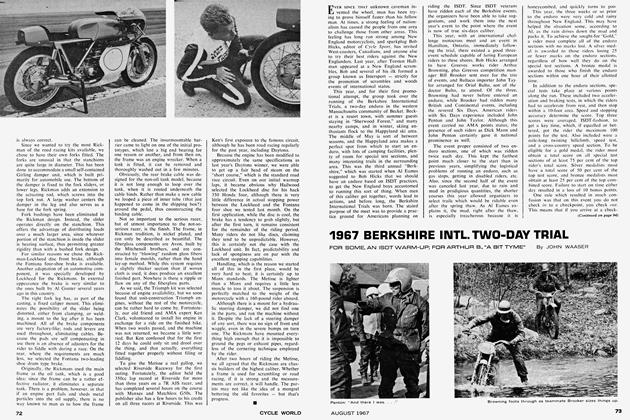

LOUDON

THE PRIVATEER'S REVENGE

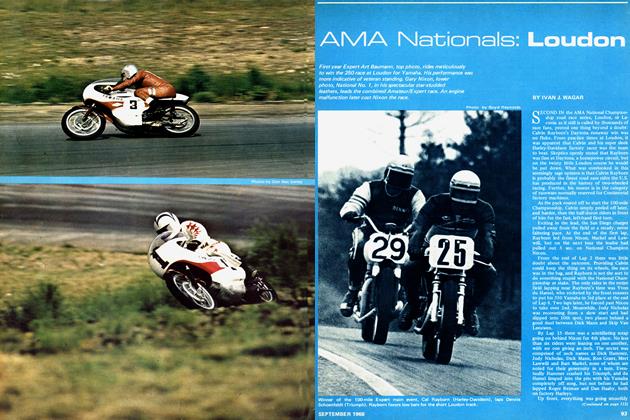

JOHN WAASER

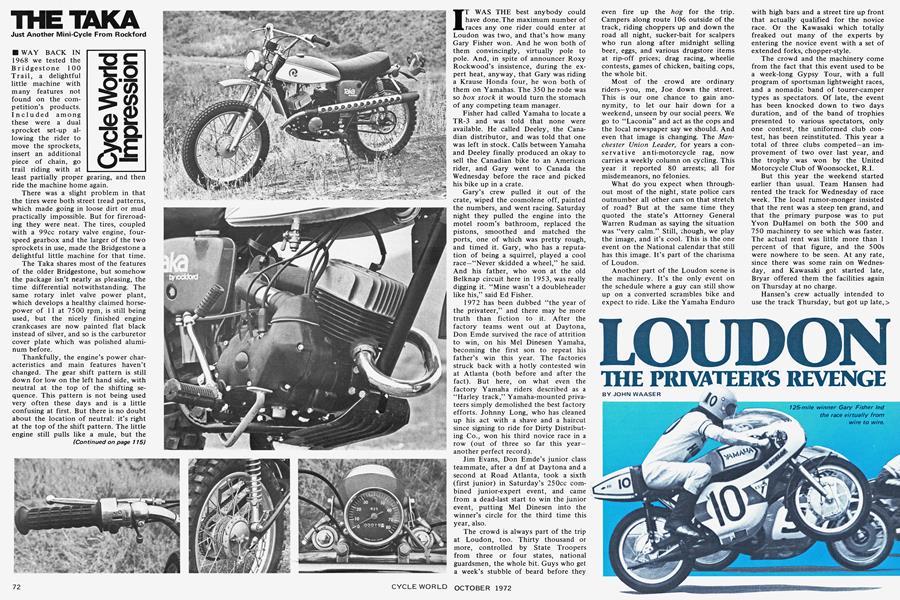

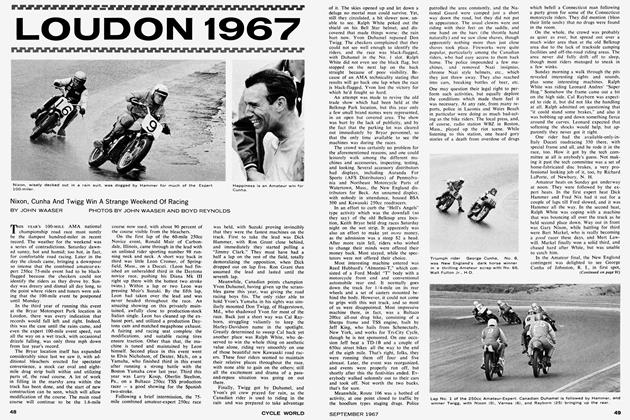

IT WAS THE best anybody could have done.The maximum number of races any one rider could enter at Loudon was two, and that's how many Gary Fisher won. And he won both of them convincingly, virtually pole to pole. And, in spite of announcer Roxy Rockwood's insistence, during the expert heat, anyway, that Gary was riding a Krause Honda four, he won both of them on Yamahas. The 350 he rode was so box stock it would turn the stomach of any competing team manager.

Fisher had called Yamaha to locate a TR-3 and was told that none were available. He called Deeley, the Canadian distributor, and was told that one was left in stock. Calls between Yamaha and Deeley finally produced an okay to sell the Canadian bike to an American rider, and Gary went to Canada the Wednesday before the race and picked his bike up in a crate.

Gary’s crew pulled it out of the crate, wiped the cosmolene off, painted the numbers, and went racing. Saturday night they pulled the engine into the motel room’s bathroom, replaced the pistons, smoothed and matched the ports, one of which was pretty rough, and timed it. Gary, who has a reputation of being a squirrel, played a cool race—“Never skidded a wheel,” he said. And his father, who won at the old Belknap circuit here in 1953, was really digging it. “Mine wasn’t a doubleheader like his,” said Ed Fisher.

1972 has been dubbed “the year of the privateer,” and there may be more truth than fiction to it. After the factory teams went out at Daytona, Don Emde survived the race of attrition to win, on his Mel Dinesen Yamaha, becoming the first son to repeat his father’s win this year. The factories struck back with a hotly contested win at Atlanta (both before and after the fact). But here, on what even the factory Yamaha riders described as a “Harley track,” Yamaha-mounted privateers simply demolished the best factory efforts. Johnny Long, who has cleaned up his act with a shave and a haircut since signing to ride for Dirty Distributing Co., won his third novice race in a row (out of three so far this year— another perfect record).

Jim Evans, Don Ernde’s junior class teammate, after a dnf at Daytona and a second at Road Atlanta, took a sixth (first junior) in Saturday’s 250cc combined junior-expert event, and came from a dead-last start to win the junior event, putting Mel Dinesen into the winner’s circle for the third time this year, also.

The crowd is always part of the trip at Loudon, too. Thirty thousand or more, controlled by State Troopers from three or four states, national guardsmen, the whole bit. Guys who get a week’s stubble of beard before they

even fire up the hog for the trip. Campers along route 106 outside of the track, riding choppers up and down the road all night, sucker-bait for scalpers who run along after midnight selling beer, eggs, and various drugstore items at rip-off prices; drag racing, wheelie contests, games of chicken, baiting cops, the whole bit.

Most of the crowd are ordinary riders—you, me, Joe down the street. This is our one chance to gain anonymity, to let our hair down for a weekend, unseen by our social peers. We go to “Laconia” and act as the cops and the local newspaper say we should. And even that image is changing. The Manchester Union Leader, for years a conservative anti-motorcycle rag, now carries a weekly column on cycling. This year it reported 80 arrests; all for misdemeanors, no felonies.

What do you expect when throughout most of the night, state police cars outnumber all other cars on that stretch of road? But at the same time they quoted the state’s Attorney General Warren Rudman as saying the situation was “very calm.” Still, though, we play the image, and it’s cool. This is the one event on the National calendar that still has this image. It’s part of the charisma of Loudon.

Another part of the Loudon scene is the machinery. It’s the only event on the schedule where a guy can still show up on a converted scrambles bike and expect to ride. Like the Yamaha Enduro

with high bars and a street tire up front that actually qualified for the novice race. Or the Kawasaki which totally freaked out many of the experts by entering the novice event with a set of extended forks, chopper-style.

The crowd and the machinery come from the fact that this event used to be a week-long Gypsy Tour, with a full program of sportsman lightweight races, and a nomadic band of tourer-camper types as spectators. Of late, the event has been knocked down to two days duration, and of the band of trophies presented to various spectators, only one contest, the uniformed club contest, has been reinstituted. This year a total of three clubs competed—an improvement of two over last year, and the trophy . was won by the United Motorcycle Club of Woonsocket, R.I.

But this year the weekend started earlier than usual. Team Hansen had rented the track for Wednesday of race week. The local rumor-monger insisted that the rent was a steep ten grand, and that the primary purpose was to put Yvon DuHamel on both the 500 and 750 machinery to see which was faster. The actual rent was little more than 1 percent of that figure, and the 500s were nowhere to be seen. At any rate, since there was some rain on Wednesday, and Kawasaki got started late, Bryar offered them the facilities again on Thursday at no charge.

Hansen’s crew actually intended to use the track Thursday, but got up late, and figured they knew enough, so didn’t bother. Other riders arrived, and course officials let them ride, telling them that Kawasaki had paid for it, and they might have to leave if the green meanies showed up, which they never did. So for the second road race in a row, any privateer who showed up at the track the day before official practice got a chance to ride. Some, like Jim Evans, who had never before seen the track took advantage of this extra practice with fewer bikes on the track to learn each corner individually; it paid off. Others who had been there on Wednesday report that the big Ks were in trouble with handling problems.

Team Hansen had the little 350cc Big Horn Singles out for each member of the team, and that may be the biggest item they were interested in testing on Wednesday. Yamaha riders were quite surprised to discover that they could not pull the little Singles up the back hill. Handling (with basically H-1R frames) is not as good as the Yamahas, but certainly better than the big bore Kawasakis. Yvon DuHamel said his 350 handled well, although it was still a bit heavy and high due to the use of the larger bike’s frame. He also noted that the brakes were not up to par, which seemed to be a fairly common complaint at the tight Loudon course (Yamaha and Harley riders both noted the same complaints).

Referring to the larger bikes, Yvon talked of a new model with 110 bhp, said to be available for Talledega. But he noted that the maximum horsepower was only produced when cold —he had to be careful when exiting corners to modulate the throttle to avoid giant wheelies, but only for the first two laps; after that the power went down and the bike wouldn’t wheelie.

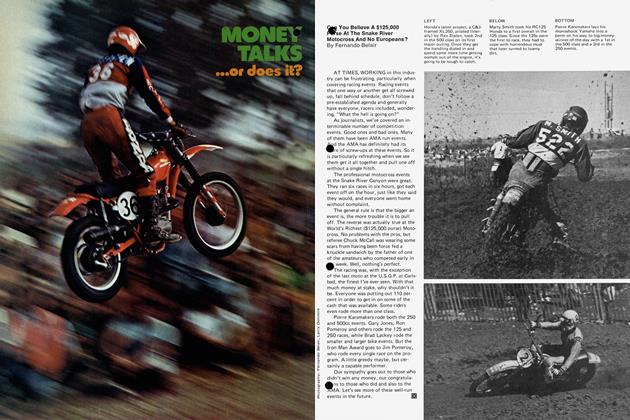

Harley Davidson had the full team there—Cal Rayborn, Mark Brelsford, Mert Lawwill, Dave Sehl, and junior rider Scott Brelsford. The course was obviously a Harley course, and Mark had won here last year. Mark was super hungry for points to gain the national championship lead. But Cal is a superb roadracer, and Sehl told me that Cal was even more hungry than Mark for a win. It’s been a couple of years since Cal won a big roadrace in the states, even though he became somewhat of a national hero in England this spring.

In practice Cal seemed faster, and his bike had a dual disc brake setup up front, which gave him the best brakes on the team. Sehl’s bike somehow had a completely wrong set of gears, and he couldn’t use high gear. While they were fixing that, Mert’s mechanic was dropping the needles in the Mikuni carbs to stop the blubbering coming out of the corners. Cal also complained of a skip, but his was more elusive in nature.

Yamaha’s team riders were glum. Their times were nowhere near good enough, and it didn’t seem likely that the Harleys and the Kawasakis would blow. They felt their chances would be better on a faster course; this one was all short drag races between the corners. Kenny Roberts held an 1 1-point lead over Mark Breisford in the national championship race, and he had to finish better than Mark to hold the lead.

With the demise of Dave Smith, Don Vesco appeared to be getting his team shaped; he’d signed on two more riders-Steve McLaughlin, who is a wellknown road racer, and Gary Scott, a top-notch dirt tracker with limited road racing experience. Scott rode Vesco’s 250, but not his 350. Team Vesco pretty much works as a team, too, something which isn’t as obvious with some of the higher-budget teams. “I’ll have to say one thing,” said McLaughlin-“when you ride for Vesco, you get a lot of work in. I never worked before; it’s far out.”

Mike Devlin, the team novice, is a paid employee at Vesco’s Shop, and does much of the rebuilding between races. Devlin, McLaughlin and Scott all pitch in willingly on race day, working on whichever machine needs it at the moment. Maybe this is less important when each bike has a full-time mechanic, but this team spirit could well be Vesco’s biggest asset.

And the hiring of Scott may be the start of another giant step forward for Don, who would like to get into dirt track racing. According to one team member, Don Vesco would desperately like to take the number one plate back to his shop, and Gary is considered to be the rider who could do it for him. But nothing definite has been worked out yet, and Gary declined a sponsorship from one of the bike magazines earlier this year.

Mel Dinesen brought his two riders, expert Don Emde and junior Jim Evans. Many riders were saying early in the week that Jim would have been better off starting out as a novice. But the offer of a sponsorship from Mel precluded that; Mel will not sponsor a novice rider. Jim petitioned the AMA for the junior status on the basis of his California roadracing experience, and was accepted. He was convinced he could beat the rest of the juniors, and was emphatic in denying that he would have been better off as a novice. Time would tell....

Dirty Distributing Company, in Atlanta, Ga., brought its southern rider, Johnny Long. Dirty is the importer of a line of Yamaha speed parts which are supposedly six months ahead of the factory hot stuff (sort of like Yoshimura is to Honda). Long has finished three races this year, and beaten the factory novice entrant (if that means anything) every time. He’s a good roadracer, of course, but you don’t make moves like his Atlanta ride unless you also have the fastest bike on the course.

Bobby J’s was there with Pierce and Stan Johnson. Ron had a superb ride in the Atlanta 250cc combined race, but this week he was having problems getting his machinery shaped, especially the 3 5 0. He blew several engines, scrounged gearing from other teams, tried different brake linings every time out, and still said he couldn’t trust his front end—it wanted to wash out.

Deeleys was down, Amol precision was up, and a host of other privateer teams were all over the pits. In fact, about the only prominent teams missing were Suzuki, who was waiting until Talledega to get its machinery legal again; K&N, who may have figured the trip was too long; and the Mulder effort, which reportedly lost its sponsorship.

The course itself was an enigma; riders who were used to it, particularly those who remember it when it was new, looked at it in terms of a deteriorating surface with a lot of bumps, and a lot of broken up asphalt. But riders who had never seen it before thought it was great—they couldn’t find any other course to compare it to. It was a rider’s course; a challenge, with lots of tight swervery. This is everybody’s reaction to the course the first time they see it, then with familiarity comes contempt.

It is an exciting course, one which demands concentration. Yet almost any brand you care to mention has won here, and since the advent of the 750cc formula, the Yamahas have done as well as any other bike. Pat Evans, viewing the course for the first time, said he thought this difference in viewpoints gave the newer riders an advantage. But the surface was undeniably going to the dogs.

Mike DeRider (DeRuytter, but his leathers say DeRider) described the surface in terms of a series of bumps a little past the “three” sign for the last turn. You’re hitting the brakes right there, and the bumps lift you right off the seat; that’s no good.

And the concession stand. Your quarter bought the usual 6-oz. Coke, while on Sunday the stand in the pits had no food at all for a while—they were out of gas, and couldn’t cook hot dogs or hamburgers, and all their sandwiches had been brought out to the front stands for the spectators. The quality of the food was nothing to brag about, especially the hamburgers—it got to the point where one young thing at the booth said, “I can’t take your money until you see the food.”

Art Barda, the Yamaha team manager, had been told that the pits would be paved and covered. He was distressed to find the usual coarse gravel for pavement.

One thing was up to par, and that deserves mention —Ray Lessard’s United Ambulance Service did a fine job all weekend. A lot of New Englanders are getting tired of Ray’s attitudes and prices, but he covers the medical scene at virtually every New England scrambles event, and all the events at Bryar, and his crew sure knows their stuff.

Jerry Greene had a bad get-off, and wasn’t sure he could ride Sunday; his arm and wrist were swollen. United’s crew taped it, applied ice, removed the tape, and applied new tape. Jerry had never seen this technique used before, but he sure knew it worked. He rode Sunday, and was able to stay near the top. And after Road Atlanta United’s drivers were also a noticeable improvement, not getting in any rider’s way all weekend. They don’t let anybody stay in the middle of the track for a lap or two, as happened at Daytona last year, either....

In most areas the officiating was prompt and not wishy-washy, but riders reported difficulty seeing the Hags from up on the flag stands, and said that many of the flaggers didn’t even get the flags out in time. When Charlie Watson said that they had been understaffed the day before, Mert Lawwill understood perfectly. “Yeah, they never ran one of these things before,” he said to nobody in particular.... And things were slow enough getting under way that Steve McLaughlin was moved to comment “One thing’s for sure—a lot of people won’t crash in practice today, ’cause we’re not having any....”

When Mike Devlin took a spill which brought down at least a total of nine machines over the next couple of laps, spectators jumped the fence to warn riders of the danger, while the flagman just stood on the stand holding the oil flag. The second rider to go down raced over and grabbed the flag, waving it right out on the track where the riders could see it, as the flagger spoke into his microphone “They’re going down like flies. It scared me.”

Practice was a Harley—and specifically a Cal Rayborn—benefit. Yvon was cutting some fast laps, of course, but Calvin got down to a 1:16.5, and everybody else just shuddered. This was the first roadrace for the new alloy Harleys, but nobody had any doubts that they could finish the race, and of course they could do it without a gas stop, which Kawasaki would require. Mert Lawwill commented that the new bikes could do a lap with about four less shifts than the old iron numbers, too.

Mert had braking problems, but other than that seemed confident in his machine. Cal’s mechanics were still looking for that elusive skip after he set the fastest practice lap, which also gave pause to the opposition. Harleys still use the wind tunnel-tested fairings and tanks, all machined parts are carefully fitted to one particular machine, and you just get the impression they’re out to win.

Gene Romero was running a bit faster than Dick Mann, and looking much more a roadracer than in previous years. Tiger Gene was also apparently faster than Dick at Atlanta.

The AMA has embarked on a new program to make sure that no rider uses any drugs, but they sure enough are being surreptitious about it. And they’re only doing it in the expert class, where most of the fast guys wouldn’t touch a pill, and would see to it that any rider who did would not be in shape to ride, anyway.

Charlie Watson announced “All you> riders, that appointment I mentioned to you is only good for another 15 minutes.” The appointment was to go pee in a bottle, said to be a sure way of determining the use of any drugs. Riders were supposed to go over there as soon as they came in, whether they had dropped out or finished the race. One rider went over as soon as he dropped out, and was told that the officials were watching the race, and to come back later. When he did so, they demanded to know why he hadn’t come earlier. It’s good to know it’s still the good old AMA.... I mean some of these racers wouldn’t know what to think if there wasn’t at least one hassle per race.

Mel Dinesen’s squad was busy sorting out some small stuff; they had the major things wired. Don Emde had a smaller-section rear tire, and Evans intended to try one also, on the 350s. The idea was faster handling, and they seemed to think it worked well. Their machines have shorter wheelbases than the factory riders, and some of the factory boys were spotted taking out links of chain to bring the adjusters to the tightest position, searching for the same effect. Jim Evans was afraid the crank might be going in his 250, and indicated Mel would pull it apart Friday night to change the crank. Later they found the front wheel slightly out of balance, which could account for the vibration, and since the crank didn’t have many miles on it, they decided to leave it alone.

At one point Gary Nixon and Yvon DuHamel went out together on their 350 Singles, and went around in a virtual dead heat. First one would gain a little, then the other would. It was neat; could you imagine a three-abreast photo finish in lime green?

Kel Carruthers was changing a tire. Roadracing rubber is pretty stiff, and he was having a time of it. “Boy, this must be a 17-in. tire....” Kel and most of the other Yamaha riders were gearing to run only five speeds in their 350s, even though the rules permit six speeds to be used. Apparently the track was laid out so that no matter how you geared it for six speeds, you had to shift in the middle of at least one corner. Five speeds worked neater. But there was some indecision as to whether to use the bottom five or the top five. Kel opted for the top five, others for the bottom.

One Yamaha rider who wasn’t having any of that nonsense was Gary Fisher, who used all six speeds. “I figure you might as well use every advantage you’ve got.” Gary practiced on his Kraus Honda, got down to the 19s (1 min. 19 sec. per lap), but figured he couldn’t keep that pace during the race without getting tired, so he rode the Yamaha on Sunday, and averaged better than 1:17 for the race. Gary had received one of three sets of a new externally adjustable Koni shock absorber to play with (the other sets went to Cal Rayborn, and Team Hansen. Cal was the only rider to use them in the race).

Gary was also using another new item from Koni—rear springs. The new shocks required a half-inch shorter spring, and they didn’t have another set of springs to cut down, so he mounted the new springs on his old Koni shocks, and ran them, changing them from his 250 to his 350. He was very happy with their performance. The springs are said to come factory matched much closer than any other brand.

Another product used by Gary which doesn’t show up in the winner’s circle too often was KLG plugs. Gary seemed to have confidence in them, and they never missed a beat. Also on KLGs was novice winner Johnny Long. Perhaps it is fitting that on a week that was kind to smaller entrants, KLG should beat Champion and NGK three races out of four.

Practically all the hot riders were on Dunlop tires, which must have shaken Goodyear up not a little. Mert Lawwill ran the American tire, trying out a new model with a little bit of a triangular pattern (finally), but the initial set he put on was way too soft.

All the while, riders were circulating, trying out this or that modification. But you can’t tell too much from practice times. The slow guys are all berserking it, and the fast guys are all cooling it. Perhaps Jim Evans put it best: “I haven’t even skidded my front wheel yet! You gotta save that stuff for the race....”

If some of the truly private equipment is deplorable at Loudon, then at least one machine deserved special mention. Randall May, of Willimantic, Conn., entered a neatly detailed machine called the Kawasingle. It was a 350cc Big Horn, with some F-5 speed parts, and a homemade chamber, in a modified H-1R frame, and it looked more “factory” than the factory bikes, right down to the name on the tank. The bike was painted Royal Blue, sort of the United States racing color, with white lettering. The “Kawa” was vertical, and the “single” was italicized, and it looked like it belonged that way. All of the detailing was as superbly done. Unfortunately, as he put it, “You escalate yourself right into trouble.” He had over $3000 invested in the bike, and still needed more power to be competitive.

Another interesting bike was Kip Komosa’s Bultaco TSS. Well, it started out in life as a TSS, but his father sold the cycle parts, keeping only the engine. Kip seized it in practice, and promptly discovered that the liner was cracked. What to do? He went home for a new barrel, and brought back the best he had—a stock Matador barrel. And that’s how he ran the race. The rest of the bike was something he concocted out of an old Metralla, fashioning items like an ingenious rear brake pedal, all by himself. Sort of the opposite end of the financial involvement scale from the Kawasingle....

In the first novice heat, Mike Devlin built a huge lead, then cooled it after the third lap. In the second, New England’s motocross hero got a great start. Jimmy Ellis came from behind to pass Johnny Long coming off the line, and led for half a lap or so. Johnny grabbed the lead then, and settled there like he owned it, as Jimmy dropped back to 5th or so. Jimmy’s Boston Cycles teammate, Timmy Rockwood, was a no-start, as his bike wouldn’t fire. The Yamaha teams were cross-swapping parts all over the place this weekend, and Jim Odom went out in the expert heat for only one lap, then pulled in (assuring himself of a start in the final) to allow his entire ignition system to be swapped onto Rockwood’s bike, so that Tim, having made an attempt to qualify, could start from the rear of the final.

(Continued on page 104)

Continued from page 78

In the novice final, Long was scorching. Ted Henter, a total unknown, had 2nd off the line, with Mike Devlin 3rd. Mike got 2nd on the third lap. Pat Evans (no relation to Jim) had a slow start, and worked his way by Devlin at about the tenth lap, at which time Long had a 35-sec. lead, and was still gaining. When the event was flagged off, Long had almost lapped 2nd place. Toward the end of the race, Devlin was cut off by a slower rider he was attempting to pass in the right-hander just before the back hill. Down he went. He immediately rose, waved his hand to show that he was all right, and stalked off the track in disgust, leaving his bike in the middle of the track. Nobody moved the bike.

Over a lap later, Devlin and a spectator raced out to remove the bike, which was only slightly inside of the fast line. All of a sudden another bike went down; the rider claims he spilled on Mike’s gas. Another went down trying to avoid the second machine; by this time somebody’s tank popped off, and there definitely was gas on the track, and virtually right on the fast line.

Bikes were going down all over the place, careening into the fence hard, and sending spectators (and riders) scurrying all over the place. Mike handed me his machine, and went out to retrieve as many more as he could. The race was red-flagged, and declared complete. Most riders did not realize that the red flag means an immediate stop. They continued to circulate slowly; Johnny Long went down after taking the red flag. Devlin had been out for several laps, and so placed 14th, while the order of some of the others was shaken up by the crash, which put down at least nine bikes.

Volunteers from the sidelines helped lay cement dust over the course. They had never done this before, and used way too much, spread it around too wide, and didn’t brush it off. The track was a mess. Jimmy Ellis finished a creditable 6th, in his fourth roadrace> entry. Pat Evans wound up 13th after blowing a crank, and a Suzuki finished 4th in the hands of Ralph Hudson, the highest placing by a non-Yamaha in recent memory in a 250cc event.

The 250cc combined event is always the super show of the weekend. The first heat showed a terrific dice between Yvon DuHamel on his Kawasaki Single, and Jerry Greene on a Yamaha, after Mike Lane took the first of many spills. Kel Carruthers was 3rd. Getting a poor start was Jim Evans, whose starts of late have been very consistently poor. One problem is that he doesn’t have a Kroeber tachometer. The stock Yamaha tachometer doesn’t work with the clutch pulled in at the line, so he doesn’t really know how high he’s revving. He can’t feed the clutch fast enough. He slowly worked his way from 1 1th to 9th, getting at least a first wave start in the final.

Other Yamaha riders have gone so far as to disconnect their tach drive gears, as these are prone to seize, locking the rear wheel, and causing a nasty accident. They run directly in the case, without a bushing. Supposedly the latest gear has cured that problem.

In the second heat, Don Emde, Jim’s teammate, got a great start, but was zapped easily by Gary Fisher. Ron Pierce moved up to duel with Emde, and these two fell to the onslaught of Gary Scott and Kenny Roberts, Kenny getting the 3rd slot on the last lap. Emde passed Pierce in a brilliant move, by going under him in the last turn, for 4th.

“I was really surprised about Yvon on the 350,” said one rider to Paul Smart. “So was I,” replied Paul. “I’ve got no excuse when he does well....”

The riders in this event got an extra lap in before the start to check out the cement over in the right-hander where Devlin had gone down, and then it was the start. Fisher grabbed an easy lead right off the pole and was never headed. Gary Scott was 2nd in the early stages. Mike Lane, who had torn up his bike in the heat, had patched it and was scorching. From a back-of-the-pack start, he was ahead of the second wave as they crossed the finish line on the first lap.

After a few laps, Kel Carruthers dropped out. This used to be his race, but he explained that the bike wasn’t running right. Since he had no chance of finishing well, he just brought it in. Scott dropped out with ignition failure. Jerry Greene dropped back, finally finishing 17th. By now the order was Fisher, DuHamel, Roberts, Smart, Emde. Jim Evans started smoking. Ray Hempstead moved up to duel with Ron Pierce. Evans had left a good dice with Jimmy Chen, and was challenging Howard Lynggard. Past Howard, he moved up quickly to the Hempstead/ Pierce battle, split them, then shook Hempstead.

(Continued on page 106)

Continued from page 105

Emde moved up to 4th and Evans took 6th, for a solid finish for Mel Dinesen. Evans wound up first junior, significant in light of the comments that he should have started as a novice. Pierce repassed Hempstead for 7th. Evans later said that for the first half of the race he had been racing other riders; when he started moving up he was racing the course.

Fisher described the race as “pretty casual,” nothing that there was nobody going down, no trouble passing slower riders, and no real competition. Kenny Robert’s fairing had broken, and the bike wasn’t running right, but he passed Yvon for 2nd.

By now Team Vesco had earned the nickname of “The Tilt Team.” The turn before the uphill straight had been renamed “Devlin’s Dump,” and the fourth turn, a left out by Bryar Pond, had gone from “Christopher’s Corner” to “Lane’s Lake.” Don had to wire home for six new fairings to be delivered to Indianapolis.

Sunday’s riders meeting settled several major points of contention—like the gas available at the track. Officials decreed that gas would be free to everything except Cal Rayborn’s motor home. Dick Mann argued that 10 seconds between waves is too long for the Loudon track; the rulebooks say 5-10 seconds. The actual time for this event was then set at five seconds.

In the first junior heat, Jim Evans and Howard Lynggard had pulled starts from the rear of the pack. It was vitally important that Jim get a good start this time, and wonder of wonders, he did. He wheelied through the pack in about 10th of the line, was up to 5th the first lap, and took 1st on the 4th lap, for a front row start in the final. Howard dropped out, and the Amol Precision BMW, it’s cylinders sticking haughtily out the sides, finished 10th, with no pit stops for chain adjustment, at least. In the second junior heat, Scott Brelsford pulled a huge wheelie at the start, as Torello Tacchi pulled a smaller one. Tacchi was on a Suzuki, having finally abandoned Norton. “Overdue,” said the nation’s perpetual junior.

Jimmy Chen had the lead on his Honda, with a swollen and stitched up right hand. That takes some doing.... Brelsford was 3rd, Greene 4th. In 2nd was “Doctor Pepper,” a local Alphabet Club (AAMRR) rider. Coming through for the white flag on the next-to-last lap, Bob got into a long wobble, looked like he had it saved, then went on his cheeks in about the hardest tumble I’ve ever seen. He walked away from it, but officials deemed him to be in shock, and ordered him into the ambulance for a ride to United’s Mobile First Aid Station. Chen came by with fastest qualifying time and a ratty sounding motor.

(Continued on page 108)

Continued from page 106

In spite of all the ballyhoo about free gas, Mel Dinesen’s crew went over to gas up and found nobody at the pump. Jim Evans didn’t have enough gas to make the race. Floyd Emde went downtown to get some, but got tied up in traffic, and didn’t get back. It was time to line up, and still no gas; Don Emde and John Hately went to try to get some out of the pump there at the track. They discovered the pump was broken, and found someone to fix it, getting gas to the line finally at the 2 min. mark. In went the gas, on went the cap—just as the 1 min. mark came up; officials would not let Evans into his first-row slot. He’d have to start from the end of the second wave.

He began a meteoric rise through the pack. By the third lap he was 10th, on the fourth lap he was 5 th. On the next lap he passed Howard Lynggard, but bobbled badly coming out of the infield hairpin, and Howard got by again. This became the hot duel of the race. For several laps Jim couldn’t get by Howard. Jim had found a weird line through the infield hairpin; he braked late, stayed inside, and drifted wider than most coming out, using first gear while everybody else was in second. It worked; he’d get by Howard, but Howard was going faster coming out, and would zap him again on the short stretch following the turn.

Finally these two closed on Jimmy Chen, in the lead, and Jerry Greene. Evans shot by the whole pack at once, and just started increasing his lead very slightly each lap. From dead-last to 1st in less than half the race, and this was the kid they said couldn’t hack it as a junior!

Meanwhile Steve Schaefer had spilled in the infield hairpin; his bike was on fire. The flames were to the pit side of the bike—the corner flagman and I (standing beyond the flagman) could not see them. But I saw Steve scooping sand on the bike; I knew it was on fire. It was Don Vesco who grabbed an extinguisher and raced clear from the pits to put the fire out. Meanwhile the flames had risen higher—the flagman could see them now, and raced with his extinguisher, just meeting Don at the fire.

Jim Evans was riding smoothly in the lead, and Greene and Chen were dropping well back—both being actually “walking wounded,” and Lynggard crashed, so the pressure was off Jim, who set a new record, anyway. Greene went out, and Jeff March came up for 3rd. Doctor Pepper came out of shock long enough to take 4th.

(Continued on page 110)

Continued from page 108

After his sixth on Saturday, Jim had planned to take several friends out to dinner on Sunday. In Victory Lane Sunday, with people crowding around him, he turned to me and whispered in incredulous tones, “I won $900!” He could afford to take his friends out in style.... He has a better-than-average deal with his tuner, and got to keep the lion’s share of his winnings. He almost got a little more than he deserved, but was too honest to take it. Bill Boyce was checking off contingencies. “Cycle News. ” “But I don’t have a Cycle News stickie. Bill, I don’t have one. Bill!” Boyce didn’t want to listen. After all, everybody has a Cycle News, stickie.... But Jim got an under-the-table sum from another paper, and one of the conditions is that he not display a Cycle News stickie.

Louis Moniz had a front row start in the first expert heat. But he was running next-to-last in the first lap. “I wish I could put on some high bars and ride on the inside edge of the track,” moaned Louis. Cal Rayborn was not up to the line yet. “We’re not waiting for Rayborn, we’re waiting because the track isn’t ready,” insisted Charlie Watson. But nobody could see any action on the track.

DuHamel scorched into the lead, with Cal 2nd and Mark Brelsford 3rd. The next lap, Cal and Yvon were neck and neck, and the crowd roared. That’s one thing about this tight track; it’s all laid out like on a TV screen, and the crowd really gets with it. Cal won, breaking his own heat record in the process. Then he took his Harley back to the pits so the mechanics could continue to try and locate the elusive miss, which was still plaguing him....

It was Kenny Robert’s chance for misfortune in the second heat; his float bowl stuck, and Bud Aksland came running up with a wrench to tap it with. They fixed it, sort of, but too late for Kenny to get into his front-row slot. He started from the rear. Kenny came up fast though, and was 7th on the first lap, then started a duel with Mike Lane before pulling ahead. Battling furiously for last place were Andy Lascoutx and

Jim Odom.

DuHamel pulled a giant lead off the line in the National, but in the first half a lap Rayborn had pulled an equal lead, and looked like he was out for vengeance. Unfortunately Cal didn’t have a machine under him. For two laps he held the lead, as Gary Fisher moved to 2nd, and then to 1st place.

On the next lap Cliff Carr, who had been 3rd from last on the Arlington Motor Sports Kawasaki, pulled into the pits for a change of plugs. “It was all we could do,” explained Kevin Cameron, his tuner. But it wasn’t enough; they were using a new type of Krober ignition, and it packed up. By now the order was Fisher, Smart, Roberts, Brelsford, DuHamel, Jim Dunn—the former Suzuki team member—looking better than ever, Cal Rayborn, and Japanese star Masahiro Wada, on a Team Hansen Kawasaki. Wada got into a frightful wobble at the infield hairpin one lap, but did not go down.

Fisher was just building his lead, and lapped all but the first five places. Rayborn’s bike had lost over a thousand rpm, and sounded distinctly raspy. John Hateley’s Triumph sounded rough and was pushing heavy smoke out the breather. Kenny Roberts was in 2nd place and gaining on both 1st and 3rd, when he went out with a non-shifting transmission. That left Gene Romero in 2nd, but his engine started to sound a bit rough toward the end, and Mark Brelsford got 2nd.

(Continued on page 114)

Continued from page 110

The strongest sounding four-stroke at the end was Dick Mann’s, and he gained a couple of spots for a 6th. DuHamel had been having shifting problems all week, and he dropped out when he could no longer rely on the transmission. Don Emde was never very far up there, and dropped out when an oil seal let go, dropping oil on the rear tire. He didn’t go down, but got into some lurid slides. The “Tilt Team” continued its bad luck. Lane tilted again, as did Jess Thomas. McLaughlin seized the crank up solid, but didn’t go down—“quickest clutch finger you ever saw.”

Scott was still running, and finished 14th. When they got it into the pits after the race they noticed the intake manifold cracked almost all the way around. “It’sa wonder it didn’t seize.” And one of the exhaust pipe retaining springs had broken. Devlin was contrite. “I was going to take the door-spring off my bike and wrap it around your pipe, but they never break....” Vesco had also borrowed a couple of sets of Fontana brakes from other Yamaha teams to use, since his riders were complaining that the stock units weren’t working.

What of Fisher? “I could go another hundred miles. Brakes were perfect. Never slid a wheel.” By winning backto-back victories in both classes, he put himself in a league with Kel Carruthers, who did it last year at Road Atlanta. It was a story-book weekend for Gary. He won well over $7000, including contingencies, and didn’t even have to split it with a sponsor (which he thought was neat). When asked later if this signaled any change in attitude—if he was going to settle down and do it some more, he said “Well, it proved I can win.” And it was mathematically the best it was possible to do. [Ö]