The Rh-70: From Drawing Board To World Champion In Five Years.

March 1 1971The RH-70: From drawing board to world champion in five years.

When the engineers at Suzuki picked a target, the worlds motocross championship, they took careful aim.

Just before the start of the 1970 Grand Prix series for the world motocross championship, Suzuki team manager Ishikawa was asked if the 250cc Suzuki RH-70 could take the title. "Without fail", he answered.

It was a bold prediction but Ishikawa’s confidence was not misplaced. Very few machines have so completely dominated a motocross season like the RH-70 did this past year. By the end of June, after taking 7 of the first eight races, Suzuki had the Maker's Cup clinched—this with 4 more races still to be run through September on the brutal European circuit. Further, by season's end, Joel Robert and Sylvain Geboers, two of the three-man Suzuki motocross team, had locked up the one-two positions in individual standings. Olle Pettersson added sixth place to cap an outstanding year.

Success stories are always impressive,

but they usually involve many long steps before the realization of a dream. To really understand what goes into winning and, more importantly, why Suzuki fielded the effort, we must look back to 1965 and '66 when the firm made the first tentative steps into motocross and began development of the RH series motorcycle. Ultimate credit must go to the man who was really the father of motocross Suzuki, Mr. Okano, general manager of research and development; and the entire racing department headed by Mr. Ishikawa.

Motocross was a significant departure. In the 1950s and early '60s all the Suzuki competition effort had been concentrated on road racing, which has vastly different machine requirements from motocross. Motocross racers must be stronger than road racers in order to withstand the steady pounding they take on rough dirt courses. The power

requirements and specialized suspensions needed, also make a road racer unsuitable for motocross work.

Initial impetus to go motocrossing came from Japanese enthusiasts, who were racing Suzukis in motocross, running successfully on stock bikes with homemade modifications until the competition arrived with speciallydesigned machines. At the urging of some influential racers, Suzuki began development of a single-purpose machine in 1965. It didn’t make it. In fact, it was as far off as the RH-70 of 1970 was right on.

The RH-66 and 67 of those years were primarily development bikes. When Suzuzki committed to investigate the European motocross scene in 1967, they sent their top rider, Kasuo Kubo, a pair of RH-67 bikes, and team manager Ishikawa off to the races. Ishikawa, it should be noted, was no novice at the game,he had been a European road race

manager. And he had an excellent technical background including a Masters degree in mechanical engineering from Michigan State.

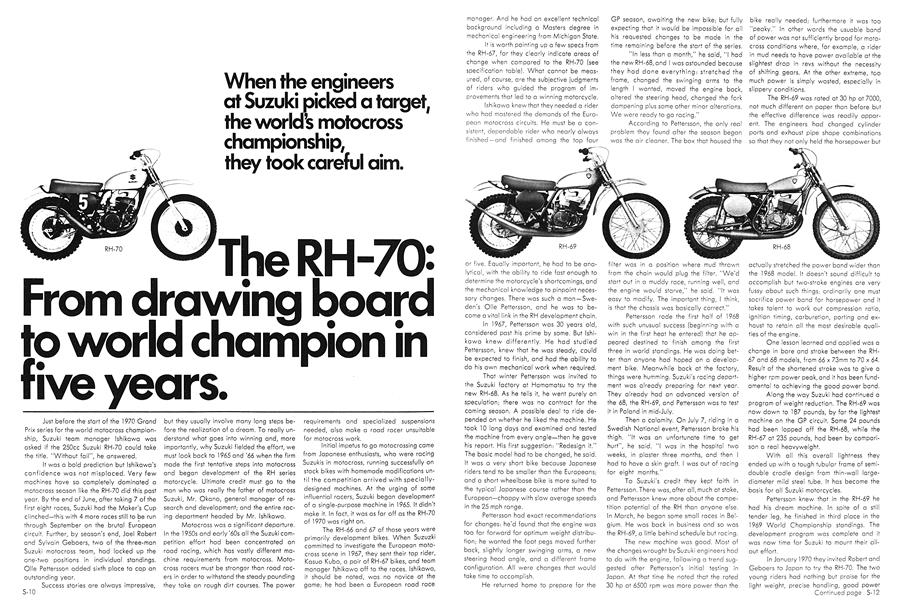

It is worth pointing up a few specs from the RH-67, for they clearly indicate areas of change when compared to the RH-70 (see specification table). What cannot be measured, of course, are the subjective judgments of riders who guided the program of improvements that led to a winning motorcycle.

Ishikawa knew that they needed a rider who had mastered the demands of the European motocross circuits. He must be a consistent, dependable rider who nearly always finished —and finished among the top four

GP season, awaiting the new bike; but fully expecting that it would be impossible for all his requested changes to be made in the time remaining before the start of the series.

"In less than a month," he said, "I had the new RH-68, and I was astounded because they had done everything: stretched the frame, changed the swinging arms to the length I wanted, moved the engine back, altered the steering head, changed the fork dampening plus some other minor alterations. We were ready to go racing."

According to Pettersson, the only real problem they found after the season began was the air cleaner. The box that housed the

bike really needed; furthermore it was too "peaky." In other words the usuable band of power was not sufficiently broad for motocross conditions where, for example, a rider in mud needs to have power available at the slightest drop in revs without the necessity of shifting gears. At the other extreme, too much power is simply wasted, especially in slippery conditions.

The RH-69 was rated at 30 hp at 7000, not much different on paper than before but the effective difference was readily apparent. The engineers had changed cylinder ports and exhaust pipe shape combinations so that they not only held the horsepower but

or five. Equally important, he had to be analytical, with the ability to ride fast enough to determine the motorcycle's shortcomings, and the mechanical knowledge to pinpoint necessary changes. There was such a man —Sweden's Olle Pettersson, end he was to become a vital link in the RH development chain.

In 1967, Pettersson was 30 years old, considered past his prime by some. But Ishikawa knew differently. He had studied Pettersson, knew that he was steady, could be expected to finish, and had the ability to do his own mechanical work when required.

That winter Pettersson was invited to the Suzuki factory at Hamamatsu to try the new RH-68. As he tells it, he went purely on speculation; there was no contract for the coming season. A possible deal to ride depended on whether he liked the machine. He took 10 long days and examined and tested the machine from every angle—then he gave his report. His first suggestion: "Redesign it." The basic model had to be changed, he said. It was a very short bike because Japanese riders tend to be smaller than the Europeans,and a short wheelbase bike is more suited to the typical Japanese course rather than the European—choppy with slow average speeds in the 25 mph range.

Pettersson had exact recommendations for changes: he'd found that the engine was too far forward for optimum weight distribution,he wanted the foot pegs moved further back, slightly longer swinging arms, a new steering head angle, and a different frame configuration. All were changes that would take time to accomplish.

He returned home to prepare for the

filter was in a position where mud thrown from the chain would plug the filter. "We'd start out in a muddy race, running well, and the engine would starve," he said. "It was easy to modify. The important thing, I think, is that the chassis was basically correct.”

Pettersson rode the first half of 1968 with such unusual success (beginning with a win in the first heat he entered) thet he appeared destined to finish emong the first three in world standings. He was doing better than anyone had hoped on a development bike. Meanwhile back at the factory, things were humming. Suzuki's racing department was already preparing for next year. They already had an advanced version of the 68, the RH-69, and Pettersson was to test it in Poland in mid-July.

Then a calamity. On July 7, riding in a Swedish National event, Pettersson broke his thigh. "It was an unfortunate time to get hurt", he said. "I was in the hospital two weeks, in plaster three months, and then I had to have a skin graft. I was out of racing for eight months."

To Suzuki's credit they kept faith in Pettersson. There was, after all, much at stake, and Pettersson knew more about the competition potential of the RH than anyone else. In March, he began some small races in Belgium. He was back in business and so was the RH-69, a little behind schedule but racing.

The new machine was good. Most of the changes wrought by Suzuki engineers had to do with the engine, following a trend suggested after Pettersson's initial testing in Japan. At that time he noted that the rated 30 hp at 6500 rpm was more power than the

actually stretched the power band wider than the 1968 model. It doesn't sound difficult to accomplish but two-stroke engines are very fussy about such things,ordinarily one must sacrifice power band for horsepower and it takes talent to work out compression ratio, ignition timing, carburetion, porting and exhaust to retain all the most desirable qualities of the engine.

One lesson learned and applied was a change in bore and stroke between the RH67 and 68 models, from 66 x 73mm to 70 x 64. Result of the shortened stroke was to give a higher rpm power peak, and it has been fundamental to achieving the good power band.

Along the way Suzuki had continued a program of weight reduction. The RH-69 was now down to 187 pounds, by far the lightest machine on the GP circuit. Some 24 pounds had been lopped off the RH-68, while the RH-67 at 235 pounds, had been by comparison a real heavyweight.

With ail this overall lightness they ended up with a tough tubular frame of semidouble cradle design from thin-wall largediameter mild steel tube. It has become the basis for all Suzuki motorcycles.

Pettersson knew that in the RH-69 he had his dream machine. In spite of a still tender leg, he finished in third place in the 1969 World Championship standings. The development program was complete and it was now time for Suzuki to mount their allout effort.

In January 1970 they invited Robert and Geboers to Japan to try the RH-70. The two young riders had nothing but praise for the light weight, precise handling, good power

Conflnued page S-12☺

band and excellent peak power of the machine. They liked the way the engine ran vibration-free right up to the 7000 rpm maximum. The steady throttle response, without the unwanted power bursts in the rev band, made the little bike tractible. They believed, they said, that the Suzuki was so much better than the machines that either of them had been riding that they could win the championship.

It was noteworthy that during hard riding tests at the bumpy motocross circuit on the Fuji Speedway, Robert was able to handle 15-minute stints without fatigue. He said that normally in the off-season he could man-

The RH-70 was the result of constant small changes which added up to a beautifully integrated racing unit. In 1969, Pettersson got a dramatic example of the magnitude of the changes when he got aboard the original machine offered him by Suzuki. He said that he could scarcely believe the difference that a few seasons had brought. Even he had not realized the overall difference that had taken place between the preliminary and final design until he rode the early bike and compared it directly to the RH-70.

The road to motocross victory had taken five years of painstaking research, engineering and competition. Why did Suzuki

bother, particularly when they had already demonstrated that their road racers were outstanding machines? The obvious answer is that the prestige of a championship is good for a company’s standing in the marketplace. Of greater importance, however, are the lessons learned which can be applied very quickly to the motorcycles people buy. The stresses of motocross gave Suzuki engineers valuable insights to every piece of their product. It is almost trite to say that racing improves the breed, but with the RH-70 and its production model sister, the TS-250R Savage, it is undeniably true.

age only five or ten minutes of serious speed, and he attributed his increased ability to the RH-70’s light weight—which made it easier to control.

The only changes requested by Robert and Geboers were minor: relocate the foot pegs and add %-inch to the swinging arms. All the machines are built basically the same, and then small individual modifications are made for each rider. As examples, Pettersson likes right-side gear shifting and a wellpadded seat, while Robert and Geboers prefer the shifter on the left and thinly padded seats. Each gets what he asks for.

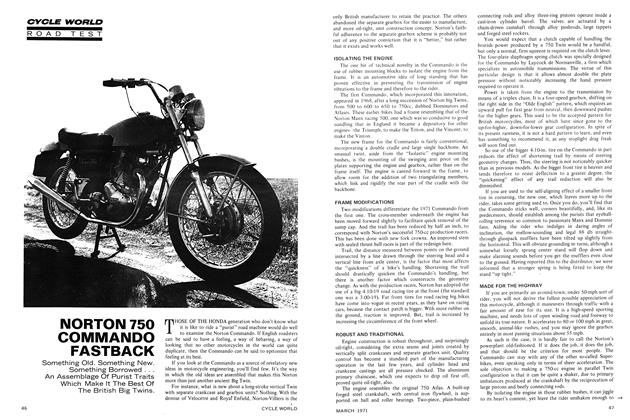

Technically, the RH-70 is very similar to the 69. The frame weighs about 16 pounds. Swinging arm assemblies are fabricated from aluminum tubing and sheet —an unusual method. Front forks, with 6.5 inches of travel, are of Japanese manufacture and similar to Cerianis. The rear dampeners, frequently criticized in Japanese motorcycles as inferior to British units, are as good as any in the world; all three team riders agree on that point.

Front hub is five-inch diameter conical, while rear hub is six inches, full width. Single leading shoe brakes are used front and rear. Fenders on the 69 were aluminum, changed to molded plastic on the 70. An aluminum fuel tank holds 1.7 gallons.

The engine makes considerable use of sand castings, practical because of its limited production for racing only. Much of the weight saving is through use of magnesium components in the engine. Transmission is five-speed, while the wet clutch is six-plate. S-12