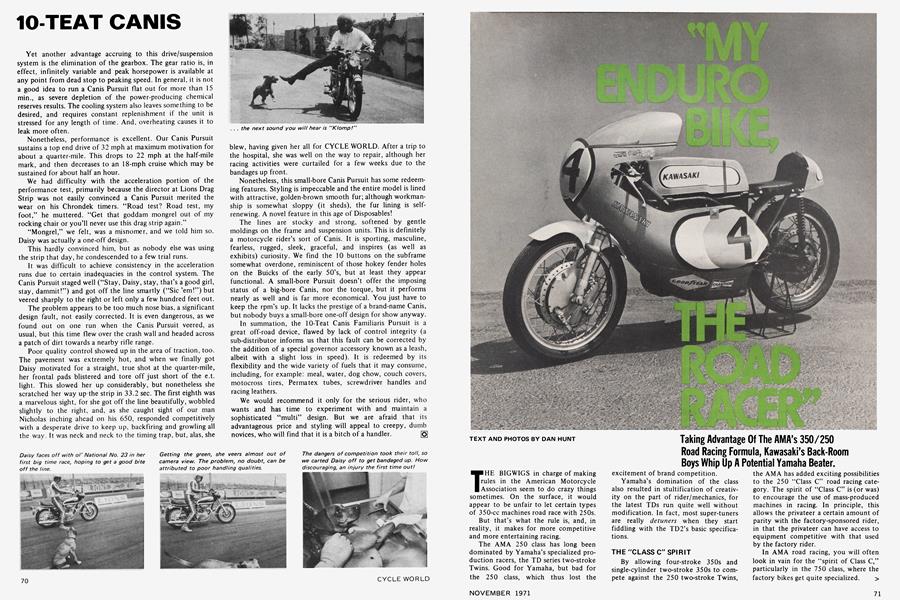

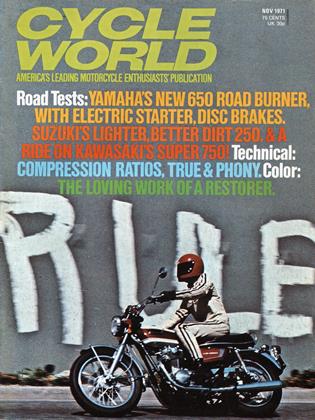

"MY ENDURO BIKE, THE ROAD RACER"

Taking Advantage Of The AMA's 350/250 Road Racing Formula, Kawasaki's Back-Room Boys Whip Up A Potential Yamaha Beater.

THE BIGWIGS in charge of making rules in the American Motorcycle Association seem to do crazy things sometimes. On the surface, it would appear to be unfair to let certain types of 350-cc machines road race with 250s.

But that’s what the rule is, and, in reality, it makes for more competitive and more entertaining racing.

The AMA 250 class has long been dominated by Yamaha’s specialized production racers, the TD series two-stroke Twins. Good for Yamaha, but bad for the 250 class, which thus lost the

excitement of brand competition.

Yamaha’s domination of the class also resulted in stultification of creativity on the part of rider/mechanics, for the latest TDs run quite well without modification. In fact, most super-tuners are really detuners when they start fiddling with the TD2’s basic specifications.

THE "CLASS C" SPIRIT

By allowing four-stroke 350s and single-cylinder two-stroke 350s to compete against the 250 two-stroke Twins,

the AMA has added exciting possibilities to the 250 “Class C” road racing category. The spirit of “Class C” is (or was) to encourage the use of mass-produced machines in racing. In principle, this allows the privateer a certain amount of parity with the factory-sponsored rider, in that the privateer can have access to equipment competitive with that used by the factory rider.

In AMA road racing, you will often look in vain for the “spirit of Class C,” particularly in the 750 class, where the factory bikes get quite specialized. >

THE 350/250 RULE

So how does the recently introduced 350/250 rule help?

Basically, it creates engine design parity, where natural differences exist. At this stage of motorcycle technique, two-stroke Twins have a power advantage over four-stroke Singles and Twins and two-stroke Singles of equal displacement. So the AMA equalizes the difference by allowing the “inferior” designs a slight displacement advantage. This is similar to the special mixed displacement classifications set up by the SCCA to provide more competitive production sports car racing.

Naturally, the special displacement allowances must be reviewed every few years to take into account design innovations that may tend to favor one model or one brand.

In fact, the only thing wrong with the AMA’s old 750/500 formula, which allowed Harley-Davidson’s flathead 750s to run with the British ohv 500s, was that it stood too long without review. No mixed displacement formula should be considered an eternal thing. Nor should the present AMA 750cc inchfor-inch formula and 350/250 formula stand forever. Times change. Models change. Public taste changes. Long standing displacement limits turn racing

into a moribund pastime. In “Class C” racing, the public availability of certain models must play an important part in the creation of these special class formulas.

THE NEW RULE'S EFFECT

The introduction of the 350/250 rule, which took place in 1970, is just now beginning to have impact. Several racers have been getting good results with the sohc Honda 350 Twin, outfitted with the Yoshimura road racing kits, which are indirect spin-offs of Honda’s “back door” involvement in clubman racing in Japan.

Dick Hammer rode a Yoshimura 350 to an excellent 3rd place behind Kel Carruthers and Cal Rayborn (both Yamaha mounted) at the AMA national at Kent, Washington.

THE BIGHORN 350

More astonishing, however, was the performance of another 350 run in both 250 classes at Kent by Junior rider Mike Lane. It didn’t appear in the results, because it didn’t finish. In the 250 Expert/Junior race, Lane crashed on an oil slick while holding 3rd. In the 250 Novice/Junior event, a condenser went belly-up while Mike was leading.

His machine is a Kawasaki, powered

by a rotary valve single-cylinder 350-cc two-stroke which began life as an enduro machine! Converting the Bighorn engine to road racing use sounds like a hopeless task. The gearbox ratios are too wide, and the engine itself is designed to put out a wide range of torque with only moderate peak horsepower.

But the racing research department at Kawasaki’s U.S. distributor was looking for a “fun” project. The prospect of making a potential winner out of an obvious underdog was quite tempting, particularly as the F5 Bighorn engine is a mass production item. The actual project was handled by Steve Whitelock, who assists chief racing mechanic Randy Hall.

FRAMING THE BIGHORN

Steve was able to scare up an Al-R-A road racing frame, which required only minor modification in the form of added brackets and a crosspiece to carry the engine. Admittedly, the Al-R-A frame is a rare item, so Steve suggests some alternative frames which could be more easily acquired by the privateer. These are:

The standard Al-R road racing frame, used to house the Kawasaki rotary valve Twin production racers.

A stock 250 Samurai (AÍ) frame.

An Hl-R (500-cc Three) road racing frame. These are quite plentiful and dealer cost is low. The Hl-R frame weighs only a few pounds more than the Al-R-A frame and would offer additional room to service the engine. As it is, Whitelock has to remove the F5 engine from the Al-R-A frame when he wants to pull the head and barrel.

RUNNING GEAR

For brakes, Whitelock had only to cannibalize the big units off the 500-cc production racing Three. These, of course, are more than adequate to haul down a 350, and presumably the Bighorn road racer could get along with something smaller and lighter.

Front forks are of the Ceriani road racing variety, while Girling or Koni shock absorbers-the choice depending on which pair hasn’t been burglarized for one of the Expert class 500s-damp the swinging arm. Center of gravity is lowered by slipping the triple clamps down over the fork tubes about an inch and by shortening the rear shock absorbers an equal amount.

ENGINE MODIFICATIONS

A certain amount of trickery is needed to make the F5 engine do a job for which it was in no way designed.

The standard Bighorn crankshaft does not take kindly to road racing revs, so Whitelock had to use a Kawasaki F81M (motocross) crankshaft, which has beefier bearings.

The stock transmission is a bit of a groaner, not only because the ratios are far apart but because the fifth gear ratio (0.715:1) is not high enough to take advantage of the engine’s top speed potential. Rider Mike Lane reports that the engine bogs down slightly shifting from 2nd to 3rd gear, and is recalcitrant to engage 5th gear without a double stab at the lever. So, the next modification will be a change in primary drive ratio (fifth gear will then be 0.950:1) and installation of an F81M close ratio gearset.

PORTING & CARBURETION

To increase power output, the modifications to the F5 consist of a larger 35-mm throat Mikuni carburetor from the Hl-R, an expansion chamber, and more radical port timing.

No modification to the rotary valve intake port, other than polishing, was necessary, as it is large enough even without polishing to accept a 34-mm carburetor. The standard port timing (110/50) is increased simply by the addition of the Bighorn “power kit”

disc valve, which yields open/close figures of 135 btc/65 ate. Scavenge port timing was modified from 57/57 to 65/65, and exhaust port timing, which is 82/82, was increased to 95/95. These porting operations are straightforward and the new timing figures are not overly radical. Nor are they necessarily the “correct” figures. They were chosen arbitrarily, and, luckily, seem to work.

The engine has a fairly flexible power band, its most useful range being from 6500 to 8500 rpm. This makes the Bighorn road racer a tiger accelerating out of corners. In some situations, Lane has been able to get through certain corners without shifting gears when the peakier Yamaha production racers have had to shift down one or two gears.

Having a flexible power curve makes the job of racing much easier and complements the hybrid machine’s light weight and good handling.

All in all, the Bighorn is an exciting example of the fun builders and riders can have with the AMA 350/250 rule. The Bighorn’s first main event win was denied because of the failure of a part costing a few cents. But it may have its day in the winner’s circle soon, perhaps before this issue reaches the newsstand. That will be an inspiration to spectators and backyard builders both.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Round Up

Round UpLess Sound More Ground

November 1971 By Joe Parkhurst -

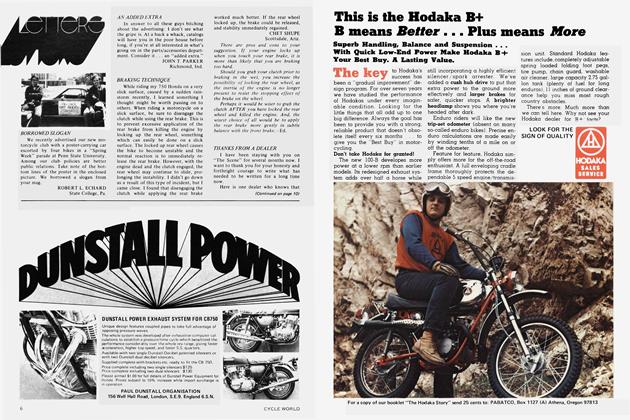

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1971 -

Departments:

Departments:"Feedback"

November 1971 -

Departments:

Departments:The Service Dept

November 1971 By Jody Nicholas -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Scene

November 1971 By Ivan J. Wagar -

...Elsewhere On the Preview Circuit

...Elsewhere On the Preview CircuitHarley-Davidson Lays It On

November 1971