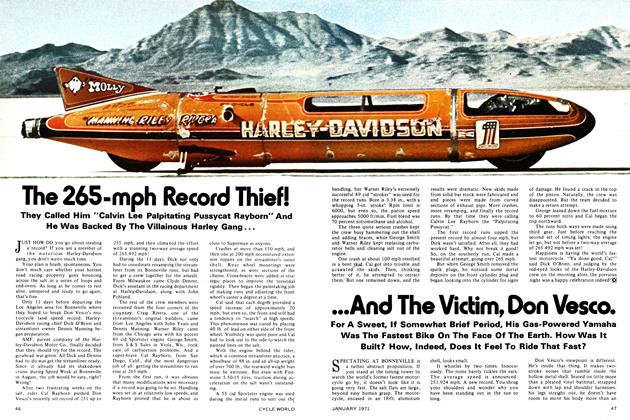

WHY WOULD A BIKE RACER TAKE UP SNOWMOBILING?

It may not be as much fun as professional AMA racing, say Bart and Yvon. But you can’t turn your back on all that prize money!

MOTORCYCLE champions Yvon du Hamel and Bart Markel have found a remedy for boredom when winter sets in. Not content to sit by the fire, these two fierce competitors have taken up snowmobile racing in a big way. They pursue this motorized snow sport with the same thrilling style they use on two wheels-win, blow, or put a hole in the fence.

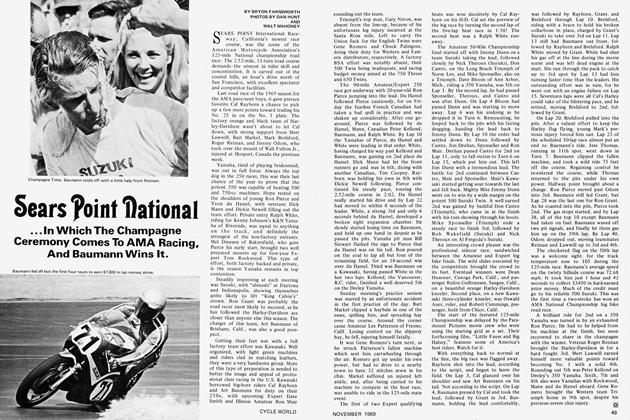

BRYON FARNSWORTH

Du Hamel started out in the winter of 1968 on a Yamaha snowmobile. During his first season he met with modest success, and was noticed by Bombardier Ltd., maker of Ski-Doo, the largest selling snowmobile in the world. The Canadian firm signed Yvon for the ’69-’70 racing season, and the No. 1 motorcycle rider in Canada didn’t let them down—he won the World Snowmobile Championship Race held at Eagle River, Wis., early in 1970.

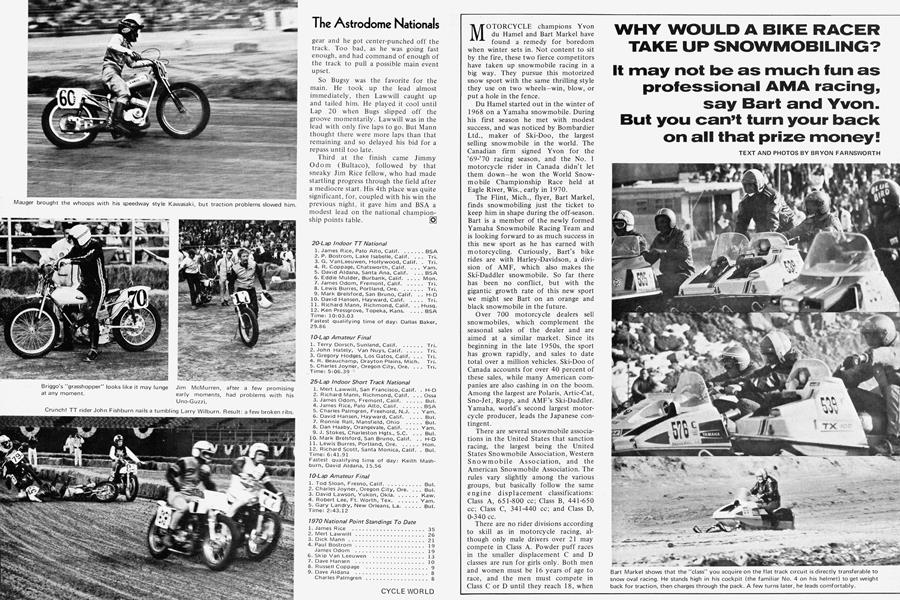

The Flint, Mich., flyer, Bart Markel, finds snowmobiling just the ticket to keep him in shape during the off-season. Bart is a member of the newly formed Yamaha Snowmobile Racing Team and is looking forward to as much success in this new sport as he has earned with motorcycling. Curiously, Bart’s bike rides are with Harley-Davidson, a division of AMF, which also makes the Ski-Daddler snowmobile. So far there has been no conflict, but with the gigantic growth rate of this new sport we might see Bart on an orange and black snowmobile in the future.

Over 700 motorcycle dealers sell snowmobiles, which complement the seasonal sales of the dealer and are aimed at a similar market. Since its beginning in the late 1950s, the sport has grown rapidly, and sales to date total over a million vehicles. Ski-Doo of Canada accounts for over 40 percent of these sales, while many American companies are also cashing in on the boom. Among the largest are Polaris, Artic-Cat, Sno-Jet, Rupp, and AMF’s Ski-Daddler. Yamaha, world’s second largest motorcycle producer, leads the Japanese contingent.

There are several snowmobile associations in the United States that sanction racing, the largest being the United States Snowmobile Association, Western Snowmobile Association, and the American Snowmobile Association. The rules vary slightly among the various groups, but basically follow the same engine displacement classifications: Class A, 651-800 cc; Class B, 441-650 cc; Class C, 341-440 cc; and Class D, 0-340 cc.

There are no rider divisions according to skill as in motorcycle racing, although only male drivers over 21 may compete in Class A. Powder puff races in the smaller displacement C and D classes are run for girls only. Both men and women must be 16 years of age to race, and the men must compete in Class C or D until they reach 18, when they may move up to Class B if they wish.

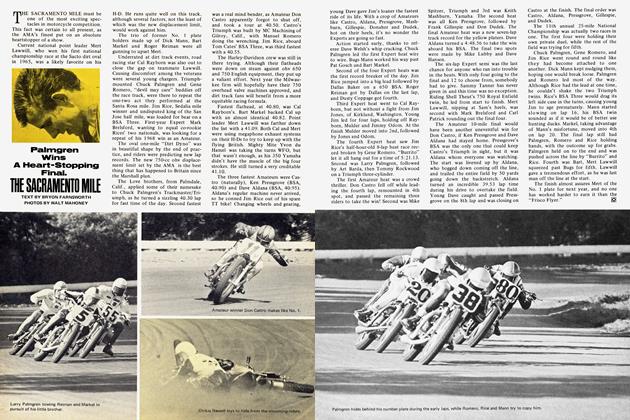

Snowmobile races are similar to motorcycle events. They include speed oval competition, which is like flattracking on a motorcycle, cross-country and drag races. Speed oval seems to be the most popular, with cross-country running a close second. The speed oval tracks range in size from one-third to one-half mile in length, with long straights and sharp, banked corners. Speeds range between 60 and 70 mph for Class A machines, with lap times in the 24second bracket. The cross-country events are similar to hare scrambles, with the drivers following a marked course. Purses range from $100 for a pot-luck local event to $50,000 cash plus $13,000 worth of contingency prizes awarded at the King’s Castle Grand Prix, held on the north shore of Lake Tahoe.

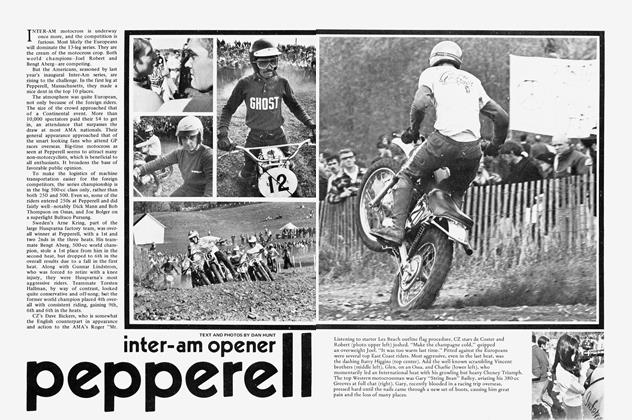

This speed oval snowmobile race held at the King’s Castle hotel and casino was the richest of its kind to date. The promoter, owner of the hotel, didn’t spare an effort in organizing the event. Held under the sanction of the Western Snowmobile Association, the Grand Prix attracted top drivers and factory teams from all over North America. Sports celebrities and top auto racing drivers including Parnelli Jones, Bobby Unser, Roger Ward, and Joe Leonard (former AMA National Champion) were present. Even Evel Knievel was there for the show. A special VIP race was ar ranged so the crowd could see their favorite sports figures aboard snow mobiles.

Both Yvon and Bart were entered, Yvon being part of the 12-man Ski-Doo factory team, while Bart headed up the Yamaha effort. Yvon was entered in two classes, the maximum allowed, while Bart had only one entry, due to his Yamaha’s engine size.

Yvon’s Class C Ski-Doo is powered by a 435-cc Rotax two-stroke Twin. This engine has two diaphragm carburetors, piston-controlled ports, and develops as much as 45 bhp at 7800 rpm. Yvon’s Class A machine has a big 771-cc Rotax Twin of the same type, putting out 75 bhp on gasoline and 91 bhp on alcohol. Mineral oil mixed with the fuel at a 32:1 ratio provides the lubrication.

Bart’s Yamaha had the biggest twostroke engine the Japanese firm produces, a 396-cc five-port Twin that puts out 48 bhp on gasoline. Itaru Hisatomi, a factory snowmobile engineer from Japan, was on hand to personally tune for Bart. The engine size of the Yamaha fell just short of the Class C maximum, but like Yamaha motorcycles, it certainly wasn’t shy any steam on the rest of the field.

Ten qualifying heats made up of 10 drivers were scheduled for the four classes. First place driver in each heat goes directly to the semi-main, with the remaining finishers given another chance in the second round of heats. So even if you didn’t win the first heat, you could still make it if you won your second. First heats had 10 drivers, second goaround had nine or less depending on the number of finishers. The semi took the top five drivers directly to the Grand Prix Main, with the remaining five contestants of the semi going to an A main. The result of all this shuffling and juggling left 10 drivers in the Grand Prix Main and 10 drivers in the A main for each class.

Overall winner in the Class A Grand Prix won $6000 cash, while the B Grand Prix winner picked up $5000. The C and D Grand Prix winners each got S4000. The A main events also paid S400 to A and B class winners and $350 to the C and D classes. All this cash plus the contingency awards amounted to quite a bundle for the rubber-tracked snow racers.

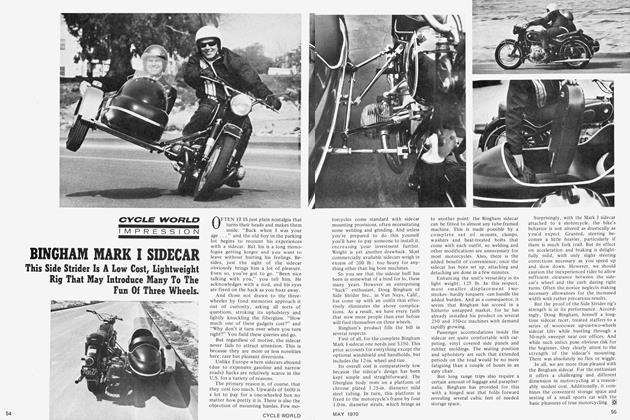

Yvon didn’t have much luck at this event. He failed to transfer out of the heats on his Class C Ski-Doo and in the big bore heats a mechanical failure stopped his first attempt. A flip in his final qualifying heat put him out of the running. Bart showed he is of champion ship caliber, whether on dirt or snow. By carefully observing the other drivers, the holes in the track, the start, and which line to take in the turns, he managed to win his qualifying heat and place 2nd in the semi-main. This put him in the Class C Grand Prix, with a chance at the big money. Running into the turns on the one-third mile~ova1 full bore, Bart would "Vee" the corner as if he were on a Kansas half-mile, and get a drive coming on the straights. The track was a series of dips and holes, and Bart's Yamaha would fly across the tops of the bumps with a rooster tail of slush spitting from the tail like a hydroplane. Bart did well considering this was his first major race. He placed 6th in the Grand Prix, and a lot of people there wondered who that nut with a No. 4 painted on his orange and black helmet was, hitting the turns wfo, with the tiller pulled hard against the stop.

Quite a number of motorcycle racers have adapted to snowmobiling, and the King’s Castle Grand Prix attracted several prominent bike riders. Darrel Triber of Spokane, Wash., was on hand with his Triber’s Tigers Ski-Doo racing team, along with Gene Thiessen, former national dirt track champ and now a BSA/Yamaha/Ski-Doo dealer in Eugene, Ore. Gary Olsen, Idaho Falls’ Triumph/ Hodaka/Ski-Doo dealer, did quite well along with teammate Jerry Miller from Monte’s Bombardier. Gary made the A main aboard his Ski-Doo, while Jerry crashed and bashed his way into the A Grand Prix with his privately owned Ski-Doo.

One driver, running around the pits with an expansion chamber in his hand, was dressed in a Bultaco tee-shirt and blue leathers; he could have stepped right out of the scene at a scrambles or short track if the weather wasn’t 35 degrees with snow on the ground.

Yvon and Bart both feel that snowmobile racing isn’t as much fun as bikes, but a racer is a racer, and if you want to make a living at it you have to be versatile. Yvon plans to contest all the 1 970 AMA National Championship Road races starting at Daytona aboard Deeley-sponsored 250 and 350 Yamahas. Bart will continue to ride for Harley-Davidson and follow the circuit gunning for the No. 1 title he held in 1966.

These two fine athletes are an example of the top-notch racers in the motorcycle fraternity. And many more, if given the opportunity, will get on the snowmobile band wagon. But they won’t find any cherry picking, for the snowmobile drivers are just like motorcycle racers. They want to win, too. [O]