REPORT FROM ITALY

CARLO PERELLI

THE PATON SAGA

Paton is 13 years old-a good age for a strictly racing enterprise building only a handful of GP racing bikes each year.

Paton came into existence following the famous Gilera-Moto Guzzi-Mondial withdrawal from GP racing at the end of the 1957 season. This decision left two died-in-the-wool and capable enthusiasts out of work: Lino Tonti and Giuseppe Pattoni.

Tonti, the brilliant designer, and Pattoni, the super-mechanic, decided not to waste the experience gained with Mondial, and so joined their efforts in a small shop in Milan. They also joined the first syllables of their names to create a new marque.

Some time later, they started producing, despite many difficulties, 125 and 175 mounts, which understandably bore some resemblance to the Mondials.

Tonti left Pattoni at the end of 1958 to join Bianchi (for which he designed the fine 250-350-500 GP Twins). The Paton name remained unchanged, and regularly was written and pronounced “Patton” by the Italian press, announcers and race-goers, surely under the impression of some connection between the Milanese bike and the American General, famous for his tanks!

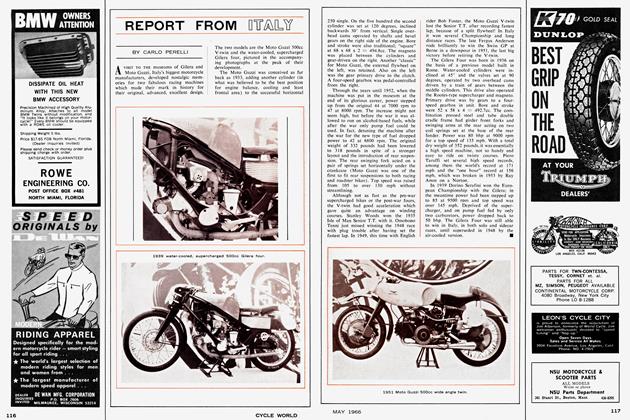

Pattoni continued to produce 125s and 175s until the early ’60s, when he decided to undertake a more ambitious project. At the opening of the 1964 Italian season, he unveiled a beautiful dohc 250 Twin with six-speed gearbox and double coil ignition, the forerunner of the present models.

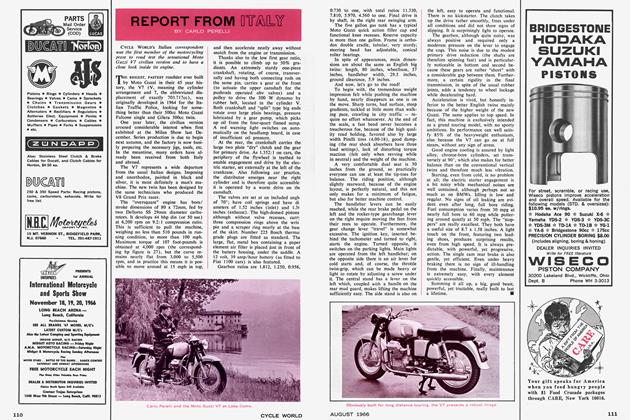

It was soon evident, however, that Pattoni’s brainchild was a bit too bulky and heavy to be really competitive (although it scored a brilliant 3rd place in the 1964 Lightweight TT with rider Alberto Pagani). In 1965 it was enlarged from 250 (53 by 56 mm) to 350 (62 by 57 mm) and finally found its groove in the classic 500 class in 1966 with a 463-cc model. In 1968 it was further increased to 476 cc and finally to 483 cc in 1969. The stroke remained the same throughout development to avoid expensive and complicated changes in the crankshaft, while the bore has most recently been extended to its limit of 74 mm, with a final capacity of 490 cc.

Like most racing bike designers and builders, Giuseppe Pattoni is far from loquacious in technical matters. And when it comes to performance figures, the 44-year-old Milanese technician used to say: “I’m poor, I can’t afford a test bench so I don't know the exact power of my bikes; but this is not important, what really matters are the lap times on th~ v~iriciis circuits."

In fact, the facilities for the building and development of his bikes are quite inadequate. Every part, from frame to gears, is built by a different specialist, mostly outside Milan, and then taken to the Paton shop for assembly. His base of operations is a big Milan garage, where Mr. “Pepp” (Pattoni’s nickname) must look after the repair and tuning of the rally and racing cars of the garage proprietor, well-known driver Giorgio Pianta, and of other sports minded customers. So the time he may devote to his beloved bikes is rather limited. Fortunately, since 1965 he has secured the full-time services of Gianemilio Marchesani, one of Italy’s best racing mechanics, himself a good rider in 125 and 250 classes since the mid ’50s.

With this situation, and the small amount of cash at hand (there are no sponsors, just customers), the development and the achievements of the Paton are widely respected with no counterpart in all the world. Pattoni and Marchesani may deserve a monument, but in line with the famous saying, “No prophet in homeland,” they receive no encouragement in Italy, and their work is more appreciated abroad.

Winner of the 1967 Italian Senior Championship and 2nd to Agostini’s MV Three in 1968 and 1969, the Paton 500 has been prominent on the international scene since 1967. Last year, the runner-up position in the World Championship seemed secure until a crash by Paton rider Billie Nelson in the Finnish GP enabled another Italian bike, the Linto, to clinch this placing.

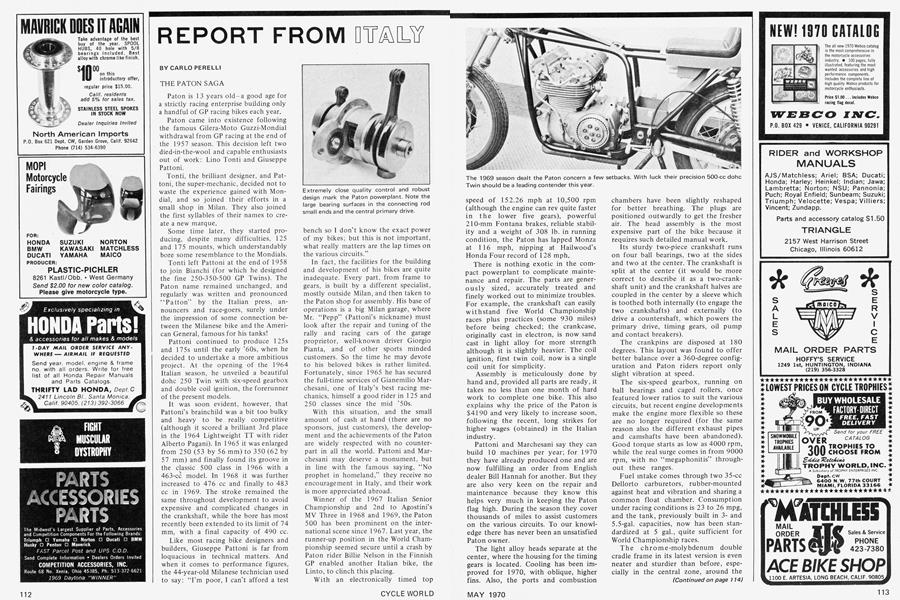

With an electronically timed top speed of 152.26 mph at 10,500 rpm (although the engine can rev quite faster in the lower five gears), powerful 210-mm Fontana brakes, reliable stability and a weight of 308 lb. in running condition, the Paton has lapped Monza at 116 mph, nipping at Hailwood’s Honda Four record of 128 mph.

There is nothing exotic in the compact powerplant to complicate maintenance and repair. The parts are generously sized, accurately treated and finely worked out to minimize troubles. For example, the crankshaft can easily withstand five World Championship races plus practices (some 930 miles) before being checked; the crankcase, originally cast in electron, is now sand cast in light alloy for more strength although it is slightly heavier. The coil ignition, first twin coil, now is a single coil unit for simplicity.

Assembly is meticulously done by hand and, provided all parts are ready, it takes no less than one month of hard work to complete one bike. This also explains why the price of the Paton is $4190 and very likely to increase soon, following the recent, long strikes for higher wages (obtained) in the Italian industry.

Pattoni and Marchesani say they can build 10 machines per year; for 1970 they have already produced one and are now fulfilling an order from English dealer Bill Hannah for another. But they are also very keen on the repair and maintenance because they know this helps very much in keeping the Paton flag high. During the season they cover thousands of miles to assist customers on the various circuits. To our knowledge there has never been an unsatisfied Paton owner.

The light alloy heads separate at the center, where the housing for the timing gears is located. Cooling has been improved for 1970, with oblique, higher fins. Also, the ports and combustion chambers have been slightly reshaped for better breathing. The plugs are positioned outwardly to get the fresher air. The head assembly is the most expensive part of the bike because it requires such detailed manual work.

Its sturdy two-piece crankshaft runs on four ball bearings, two at the sides and two at the center. The crankshaft is split at the center (it would be more correct to describe it as a two-crankshaft unit) and the crankshaft halves are coupled in the center by a sleeve which is toothed both internally (to engage the two crankshafts) and externally (to drive a countershaft, which powers the primary drive, timing gears, oil pump and contact breakers).

The crankpins are disposed at 180 degrees. This layout was found to offer better balance over a 360-degree configuration and Paton riders report only slight vibration at speed.

The six-speed gearbox, running on ball bearings and caged rollers, once featured lower ratios to suit the various circuits, but recent engine developments make the engine more flexible so these are no longer required (for the same reason also the different exhaust pipes and camshafts have been abandoned). Good torque starts as low as 4000 rpm, while the real surge comes in from 9000 rpm, with no “megaphonitis” throughout these ranges.

Fuel intake comes through two 35-cc Dellorto carburetors, rubber-mounted against heat and vibration and sharing a common float chamber. Consumption under racing conditions is 23 to 26 mpg, and the tank, previously built in 3and 5.5-gal. capacities, now has been standardized at 5 gal., quite sufficient for World Championship races.

The chrome-molybdenum double cradle frame in its latest version is even neater and sturdier than before, especially in the central zone, around the footrests and the swinging arm spindle. The swinging arm also has been reinforced. Tires are 3.00-18 front and 3.50 rear; suspension is by Ceriani.

(Continued on page 114)

BENELLI ON FIRE

A big fire at the Benelli works, causing damage worth $100,000, has delayed preparation of the new 350 and 500 GP Fours since much precious racing material was destroyed. Every effort is being made to have the machines ready for the TT. In the meantime however, any offers to Hailwood, as reported by the English press, have been denied by factory executives. With a kind gesture, Benelli presented Tarquinio Provini with a 250 Four, in perfect condition, as a souvenir of his 1 965-1 966 golden days with this mount. He has it displayed in his Protar offices.

FRAME SPECIALISTS

Frame expert Othmar “Marly” Drixl, well-known for his forward looking frame designs, has produced another interesting layout. In cooperation with the Mainini Brothers, one of the largest Italian dealers with a multi-store shop near Milan equipped with an expensive test bench, he has built a super low and light frame to house the Golden Wing 125 Aermacchi (also the Yamaha Twin). Height at top of steering column is 29 in., at saddle 24.6 in., with a total weight of 163 lb. Significantly, wheelbase is 2 in. longer than standard (from 48.4 in to 50.3 in.), which, combined with the low profile, makes the bike appear very long. The frame is made from smallish 0.78-in, diameter tubes, while the box section rear swing ing arm appears particularly sturdy.

The engine is also unusual, now incorporating a rotary valve and a huge 32-mm carburetor on the left, where the contact breakers are also positioned (the standard Golden Wing uses a 17-mm instrument and flywheel magneto). First tests have been satisfactory regarding performance, so replicas of this machine are likely to come.

But Drixl isn’t the only special frame designer and builder in Italy. Near the Milan airport is found the fine Belletti workshop where father and son, helped by a handful of other experts, build small airplane fuselages and engine supports along with Paton and Linto frames. It is one of the very few enterprises in Italy authorized by the Italian Government and the Air Ministry to execute every type of welding on high class materials such as chromemolybdenum. Needless to add, the Bellettis are motorcycle enthusiasts. In early postwar days, the senior Belletti built a complete two-stroke lightweight from raw material: the only purchased parts were wheels and tires, carburetor and magneto! Furthermore, he rode it successfully in long distance trials! If you have some $430 to spend, you can order a Belletti special one-off frame in chrome molybdenum, also available for roadster mounts. [Oj