THE SCENE

IVAN J. WAGAR

IF there is an Olympics of motorcycling, it must surely be the International Six Days Trial. For almost a week, men and machines are faced with rugged terrain, tight time schedules, and tests to prove rider mechanical ability and motorcycle durability.

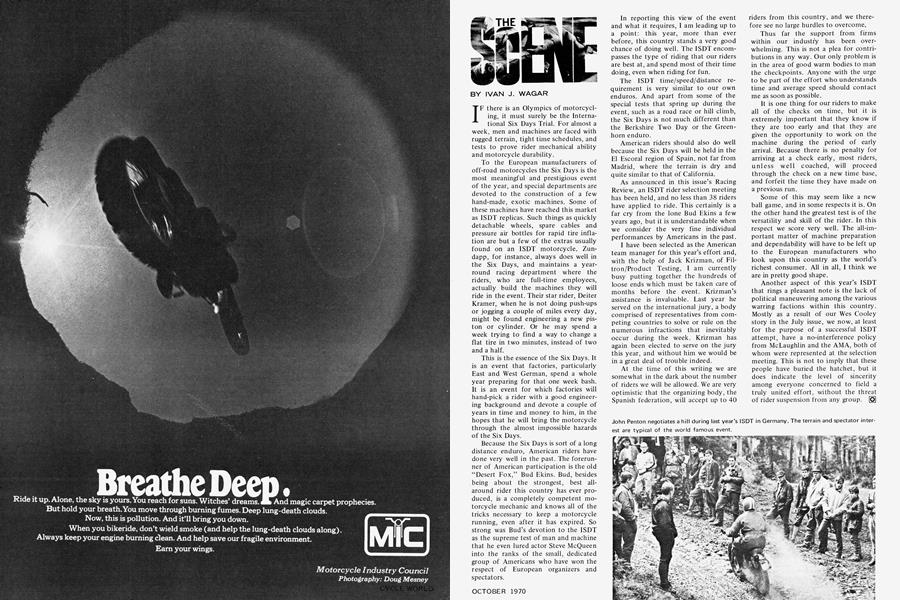

To the European manufacturers of off-road motorcycles the Six Days is the most meaningful and prestigious event of the year, and special departments are devoted to the construction of a few hand-made, exotic machines. Some of these machines have reached this market as ISDT replicas. Such things as quickly detachable wheels, spare cables and pressure air bottles for rapid tire inflation are but a few of the extras usually found on an ISDT motorcycle. Zundapp, for instance, always does well in the Six Days, and maintains a yearround racing department where the riders, who are full-time employees, actually build the machines they will ride in the event. Their star rider, Deiter Kramer, when he is not doing push-ups or jogging a couple of miles every day, might be found engineering a new piston or cylinder. Or he may spend a week trying to find a way to change a flat tire in two minutes, instead of two and a half.

This is the essence of the Six Days. It is an event that factories, particularly East and West German, spend a whole year preparing for that one week bash. It is an event for which factories will hand-pick a rider with a good engineering background and devote a couple of years in time and money to him, in the hopes that he will bring the motorcycle through the almost impossible hazards of the Six Days.

Because the Six Days is sort of a long distance enduro, American riders have done very well in the past. The forerunner of American participation is the old “Desert Fox,” Bud Ekins. Bud, besides being about the strongest, best allaround rider this country has ever produced, is a completely competent motorcycle mechanic and knows all of the tricks necessary to keep a motorcycle running, even after it has expired. So strong was Bud’s devotion to the ISDT as the supreme test of man and machine that he even lured actor Steve McQueen into the ranks of the small, dedicated group of Americans who have won the respect of European organizers and spectators. In reporting this view of the event and what it requires, I am leading up to a point: this year, more than ever before, this country stands a very good chance of doing well. The ISDT encompasses the type of riding that our riders are best at, and spend most of their time doing, even when riding for fun.

The ISDT time/speed/distance requirement is very similar to our own enduros. And apart from some of the special tests that spring up during the event, such as a road race or hill climb, the Six Days is not much different than the Berkshire Two Day or the Greenhorn enduro.

American riders should also do well because the Six Days will be held in the El Escoral region of Spain, not far from Madrid, where the terrain is dry and quite similar to that of California.

As announced in this issue’s Racing Review, an ISDT rider selection meeting has been held, and no less than 38 riders have applied to ride. This certainly is a far cry from the lone Bud Ekins a few years ago, but it is understandable when we consider the very fine individual performances by Americans in the past.

I have been selected as the American team manager for this year’s effort and, with the help of Jack Krizman, of Filtron/Product Testing, I am currently busy putting together the hundreds of loose ends which must be taken care of months before the event. Krizman’s assistance is invaluable. Last year he served on the international jury, a body comprised of representatives from competing countries to solve or rule on the numerous infractions that inevitably occur during the week. Krizman has again been elected to serve on the jury this year, and without him we would be in a great deal of trouble indeed.

At the time of this writing we are somewhat in the dark about the number of riders we will be allowed. We are very optimistic that the organizing body, the Spanish federation, will accept up to 40 riders from this country, and we therefore see no large hurdles to overcome.

Thus far the support from firms within our industry has been overwhelming. This is not a plea for contributions in any way. Our only problem is in the area of good warm bodies to man the checkpoints. Anyone with the urge to be part of the effort who understands time and average speed should contact me as soon as possible.

It is one thing for our riders to make all of the checks on time, but it is extremely important that they know if they are too early and that they are given the opportunity to work on the machine during the period of early arrival. Because there is no penalty for arriving at a check early, most riders, unless well coached, will proceed through the check on a new time base, and forfeit the time they have made on a previous run.

Some of this may seem like a new ball game, and in some respects it is. On the other hand the greatest test is of the versatility and skill of the rider. In this respect we score very well. The all-important matter of machine preparation and dependability will have to be left up to the European manufacturers who look upon this country as the world’s richest consumer. All in all, I think we are in pretty good shape.

Another aspect of this year’s ISDT that rings a pleasant note is the lack of political maneuvering among the various warring factions within this country. Mostly as a result of our Wes Cooley story in the July issue, we now, at least for the purpose of a successful ISDT attempt, have a no-interference policy from McLaughlin and the AMA, both of whom were represented at the selection meeting. This is not to imply that these people have buried the hatchet, but it does indicate the level of sincerity among everyone concerned to field a truly united effort, without the threat of rider suspension from any group. £0]

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Department

DepartmentRound Up

October 1970 By Joe Parkhurst -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1970 -

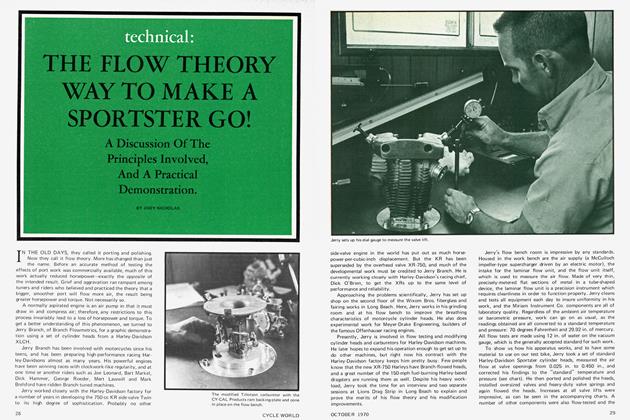

Special Technical Feature

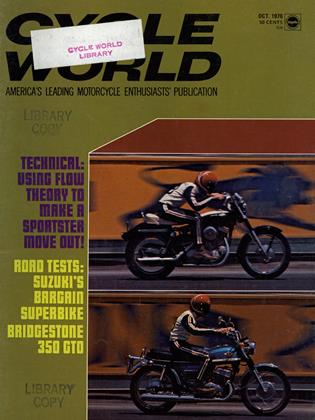

Special Technical FeatureTechnical: the Flow Theory Way To Make A Sportster Go!

October 1970 By Jody Nicholas -

Features

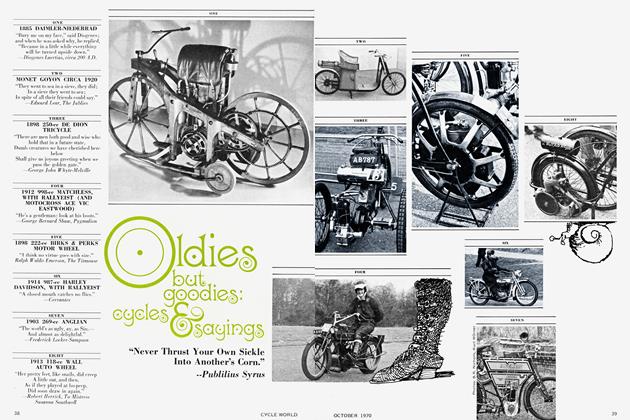

FeaturesOldies But Goodies: Cycles & Sayings

October 1970 By Publilius Syrus -

Features

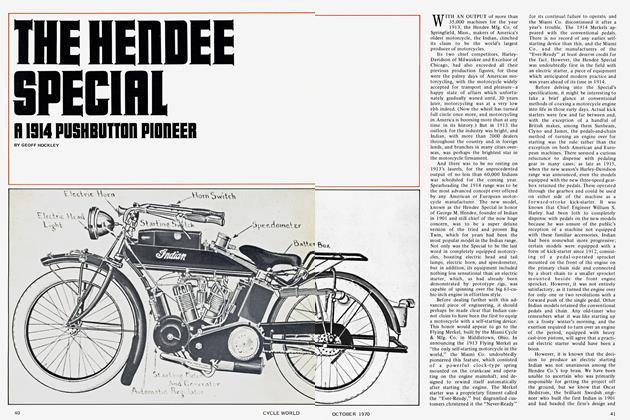

FeaturesThe Hendee Special

October 1970 By Geoff Hockley -

Competition

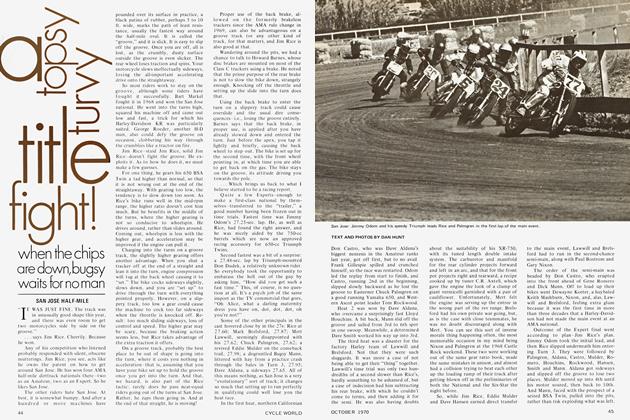

CompetitionA Topsy Turvy Title Fight!

October 1970 By San Jose Half-Mile