A VISIT TO THE ZUNDAPP SPORTING DEPARTMENT

Reliability goes, only when the South Wind blows

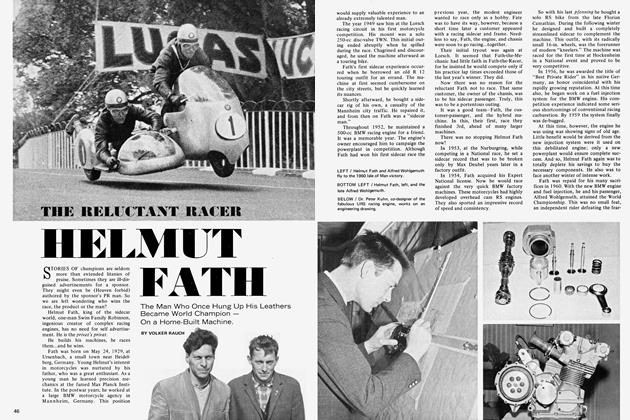

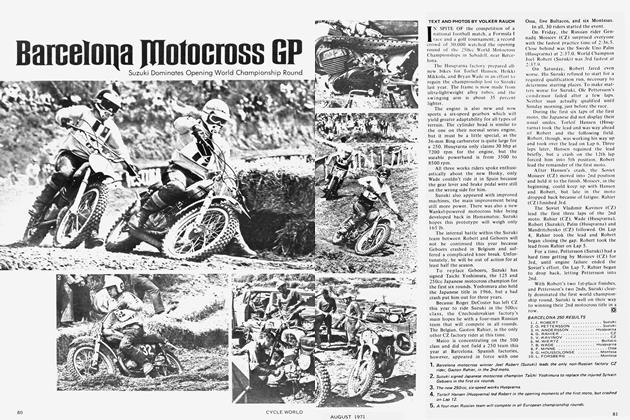

VOLKER RAUCH

RELIABILITY can be a dowdy sort of word, but in Zundapp’s case, it is exciting. What makes it so is the way these feisty motorcycles from Germany brave rain-sleet-snow-mud adversity to carry their riders, and American ones like Dave Ekins, to international victories.

Served up with strong performance, reliability relates better to the common man, the motorcycle buyer, than does blinding speed and power. So Zundapp has always made this virtue their motto, testing it and demonstrating it to good advantage in the type of competition where it shines—the reliability trial. This they did from the very beginning—only five Zundapps existed when two of them won 1st and 2nd places in the Wurgau Mountain Trial in October 1921. Since then, their interminable successes with close-to-production, or entirely production, machines have proved the brand’s claim to fame.

During all these years, Zundapp deliberately abstained from building special out-of-series machines for the running of international road races. Their aim was to prove efficiency and reliability of the production models, and no doubt this was the correct attitude. They concluded that experiences gathered from reliability events might be employed for series production more quickly than those rendered by special machines, which very often have little in common with production models.

In 1958, Zundapp gave up their Nurnberg factory and moved to the Munich plant. Production now was focused on smaller engine sizes, in particular the 50-cc class, and this naturally meant that Zundapp stressed crosscountry competition in these low classes. At the time, the 50-cc motorcycle began its own way, and soon had nothing but its capacity in common with other, popular types of motorbikes, which gained such an enormous importance for the market.

Intense competition now required a special, “works” approach in preparing models for endurance meets. When building up a new cross-country sporting department in Munich, Zundapp people were eager not to miss the dot on the “i”, and employed as their chief one of the best known riders of the big Zundapp-KS of preand postwar time, Georg Weiss. He soon expanded Zundapp’s participation to classes higher than the 50-cc category, and in 1961 engaged Dieter Kramer as rider for the 75-cc motorcycle. Kramer became a member of the Zundapp experimental department one year later.

In 1964, Weiss took Kramer into his racing department and charged him with the building of new serial racing machines for the 50-cc to 175-cc category. To be successful in Germany and, above all, in international cross-country events, Zundapp required light machines with high engine output and just as high Zundapp reliability.

Dieter Kramer was the perfect man for this tremendous task. He had years of practice in cross-country riding and had gathered a great deal of experience in the tuning of high performance twostrokes.

He began his career as a sportsman rider on a private 50-cc Kreidler in 1955. In 1958, he won the Württemberg championship on board a 250-cc Maico; one year later, Kreidler hired Kramer as works rider and took him to Kornwestheim. But his best years in cross-country were yet to come; when he started to ride for Zundapp, he became German champion on the 100-cc Zundapp in 1963 and 1964. In 1966 and 1967, he again won the German championship for Zundapp, this time in the 125-cc class.

His successes demonstrated not only clear proof of his sporting qualification, but also showed his technical ability as a designer and engineer. He himself had done a good deal of work on the construction of the machines. Other riders also won in the 50-cc to 175-cc categories mounted on Zundapps.

In 1967, the German cross-country championship of the up-to-50-cc class was won for the fifth successive time by Dieter’s brother, Volker, who is as talented a rider as is Dieter.

Dieter had been in charge of the development of racing machines for a year, when, during the DMV Two-Days’ Trip at Eschwege in 1965, he demonstrated how racing models of an approved series should be built to compete on an international basis. The engines he treated not only rendered sufficient output, but, thanks to their light tubular frames (with Zundapp’s own excellent telescopic fork), they left all their international rivals behind.

Zundapp’s competitors also had been eager to bring high performance machines into the races. But they had been changed little from the serial models, so were less lucky.

Dieter Kramer’s ideas are supported by the fact that today practically the same Zundapp racing models are run although some changes have been made. The tubular frame chassis proved weak during the Six Days’ Running at Spindlermuhle in 1963. Today it is made of chrome-molybdenum steel. This meets the increased stress of the international cross-country events. Chrome-molybdenum steel not only guarantees the desired low weight (thanks to the thinwalled tubes permissible), but also the necessary strength and rigidity.

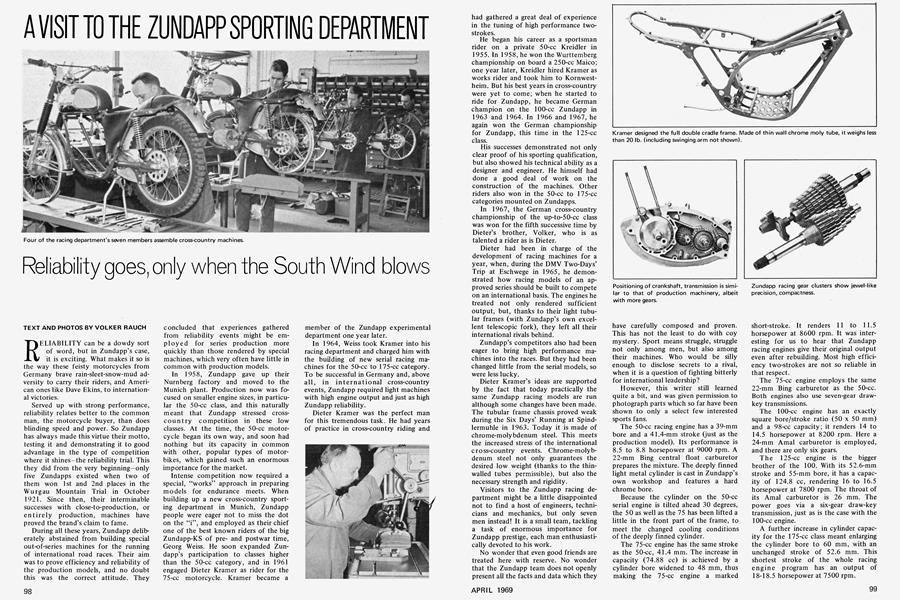

Visitors to the Zundapp racing department might be a little disappointed not to find a host of engineers, technicians and mechanics, but only seven men instead! It is a small team, tackling a task of enormous importance for Zundapp prestige, each man enthusiastically devoted to his work.

No wonder that even good friends are treated here with reserve. No wonder that the Zundapp team does not openly present all the facts and data which they have carefully composed and proven. This has not the least to do with coy mystery. Sport means struggle, struggle not only among men, but also among their machines. Who would be silly enough to disclose secrets to a rival, when it is a question of fighting bitterly for international leadership?

However, this writer still learned quite a bit, and was given permission to photograph parts which so far have been shown to only a select few interested sports fans.

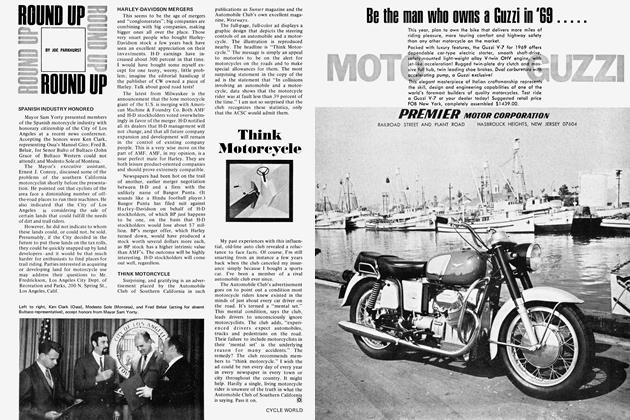

The 50-cc racing engine has a 39-mm bore and a 41.4-mm stroke (just as the production model). Its performance is 8.5 to 8.8 horsepower at 9000 rpm. A 22-mm Bing central float carburetor prepares the mixture. The deeply finned light metal cylinder is cast in Zundapp’s own workshop and features a hard chrome bore.

Because the cylinder on the 50-cc serial engine is tilted ahead 30 degrees, the 50 as well as the 75 has been lifted a little in the front part of the frame, to meet the changed cooling conditions of the deeply finned cylinder.

The 75-cc engine has the same stroke as the 50-cc, 41.4 mm. The increase in capacity (74.88 cc) is achieved by a cylinder bore widened to 48 mm, thus making the 75-cc engine a marked short-stroke. It renders 11 to 11.5 horsepower at 8600 rpm. It was interesting for us to hear that Zundapp racing engines give their original output even after rebuilding. Most high efficiency two-strokes are not so rehable in that respect.

The 75-cc engine employs the same 22-mm Bing carburetor as the 50-cc. Both engines also use seven-gear drawkey transmissions.

The 100-cc engine has an exactly square bore/stroke ratio (50 x 50 mm) and a 98-cc capacity; it renders 14 to 14.5 horsepower at 8200 rpm. Here a 24-mm Amal carburetor is employed, and there are only six gears.

The 125-cc engine is the bigger brother of the 100. With its 52.6-mm stroke and 55-mm bore, it has a capacity of 124.8 cc, rendering 16 to 16.5 horsepower at 7800 rpm. The throat of its Amal carburetor is 26 mm. The power goes via a six-gear draw-key transmission, just as is the case with the 100-cc engine.

A further increase in cylinder capacity for the 175-cc class meant enlarging the cylinder bore to 60 mm, with an unchanged stroke of 52.6 mm. This shortest stroke of the whole racing engine program has an output of 18-18.5 horsepower at 7500 rpm.

All racing engines have a light alloy barrel with chrome-plated bore, just like the production models. And, as all high efficiency two-strokes of today, they have a third scavenging channel opposite the exhaust port, which, however, is not so much meant to increase the output, as to aid the cooling of the piston. The exhaust port is webbed—a typical feature of wide port two-strokes—to prevent the piston ring from being snagged in the port.

To reach a higher pre-compression, the racing engines have a somewhat shorter connecting rod than the production models. The discal crankshaft (which, because of its high degree of rigidity, can serve a full running season!) is provided with a Durkopp needle bearing with steel cage on the big end. That very needle bearing is a special design of Kramer and the Durkopp works for Zundapp engines. Thus, the crankshaft, which once caused so much headache to Zundapp engineers, no longer presents difficulties today.

A problem during last year’s racing season was the electrical equipment (i.e., flywheel ignition with outer ignition coil). The flywheels broke off, over and over again. Finally Bosch tried turning one-piece flywheels from billets for the high revving engines. But Zundapp’s competitors (who are fighting the same problem) believe this does not yet seem to be the solution.

The Mahle cast pistons (not forged, simply because there is no need for it) are equipped with needle-bearing piston-pins.

All engines now have a fan-shaped head fin configuration, which evidently provides the best cooling conditions (and a minimum of dirt accumulation). Zundapp formerly employed this fan shape for their engines on the air-cooled Bella scooter.

Lubrication of the racing models— just as the serial ones—is accomplished by means of an oil/gasoline mixture, the mixing ratio being 25:1. Dieter Kramer is well aware of the fact that a reduction of the oil percentage in the mixture would bring additional output. But, there has not been enough time for complete fuel mix testing. The Zundapp team is also afraid that there might arise a mix-up of fuel preparation when running international races, if their team’s mix differed greatly from the common 25:1 ratio.

Zundapp engines, by the way, exhibit an astonishing phenomenon. Power output over the entire rpm range drops whenever southerly gales arise around Munich!

Because the 50-cc type is the most important engine of Zundapp’s serial production, new ideas and power increasing concepts are naturally tested on the 50-cc racing model first. Thus, during the last winter season, Dieter Kramer again spent several months working on the smallest engine, passing the improvements on to the bigger models later. Dieter admits that you may easily be confronted by unwelcome surprises in attempting to reach an equivalently higher power output with the larger engines.

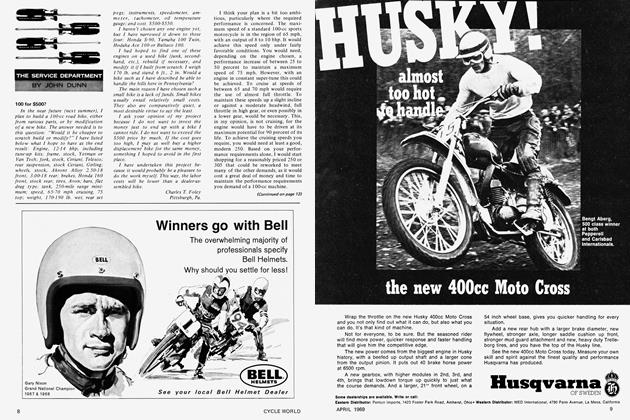

All racing machines have a standard frame made of thin-walled chromemolybdenum steel tubes. The wheel base is about 52 in. The frame is provided with a telescopic fork at the front. The Girling telescopic legs (the best available at present) allow 4 in. of travel at the wheel axle. The telescopic fork (with hydraulic shock absorber), designed according to a suggestion once given by Sengfelder, permits a stroke of 6 in. The frame weighs just under 20 lb.

The 50-cc and 75-cc models have a slightly upwards tilted engine mounted at the front of the frame to give the desired cooling effect by an erected cylinder. The bigger engines, from 100 cc upward, are normally positioned (Kramer designed for them a special case with only 20-degree cylinder tilt). However, the better cooling conditions of the big engines are accompanied by a somewhat higher tendency to vibrate.

On all models, the 21-in. front wheel carries a 2.50-in. tire, while the tire on the 18-in. rear wheel is 3.00 in. on the 50, and 3.50 in. on the larger models. With tools and with the tank full of fuel, the Zundapp weighs about 190 lb. The fuel tank, which is made of altered production parts, has a capacity of 2.5 gal.

During this writer’s visit to the Zundapp racing department, all there were busily working for the new racing season. Meanwhile, the first races had been run—such as the races for German cross-country championship and the international Several Days’ Tours.

With such careful preparation and mechanical ingenuity, the team is sure to do well as the 1969 season progresses.