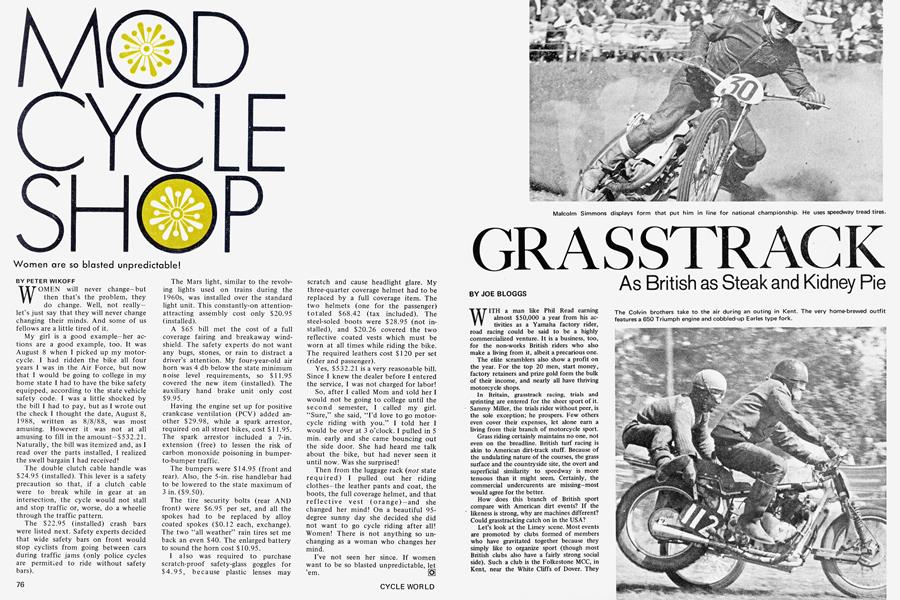

GRASSTRACK

As British as Steak and Kidney Pie

JOE BLOGGS

WITH a man like Phil Read earning almost $50,000 a year from his activities as a Yamaha factory rider, road racing could be said to be a highly commercialized venture. It is a business, too, for the non-works British riders who also make a living from it, albeit a precarious one.

The elite scramblers also show a profit on the year. For the top 20 men, start money, factory retainers and prize gold form the bulk of their income, and nearly all have thriving motorcycle shops.

In Britain, grasstrack racing, trials and sprinting are entered for the sheer sport of it. Sammy Miller, the trials rider without peer, is the sole exception; he prospers. Few others even cover their expenses, let alone earn a living from their branch of motorcycle sport.

Grass riding certainly maintains no one, not even on the breadline. British turf racing is akin to American dirt-track stuff. Because of the undulating nature of the courses, the grass surface and the countryside site, the overt and superficial similarity to speedway is more tenuous than it might seem. Certainly, the commercial undercurents are missing-most would agree for the better.

How does this branch of British sport compare with American dirt events? If the likeness is strong, why are machines different? Could grasstracking catch on in the USA?

Let’s look at the Limey scene. Most events are promoted by clubs formed of members who have gravitated together because they simply like to organize sport (though most British clubs also have a fairly strong social side). Such a club is the Folkestone MCC, in Kent, near the White Cliffs of Dover. They have their own Downland acreage at nearby Rhodes Minnis. Some members get their kicks from putting on meetings; some from riding in them. Competitors from visiting clubs form some three-quarters of the entry; Folkestone members may compete elsewhere on a reciprocal-membership basis.

Courses are sited on cow pastures. The field-a 10-acre spread will do fine after the late-May crop of hay is garnered-is harrowed at the start of the season. A roller might be used, too, though this is close to pampering the lads.

If, during the week, moles cause the meadow to sprout warts, that’s just too bad—a few races will soon flatten the molehills. (Moles are a great farming pest in England.)

A course receives little annual attention other than reseeding of worn patches in the closed season. Plowing finishes (from English agriculture, much of which still lacks two-way reversible plows) leave interesting troughs. These troughs, which may be taken at a shallow angle by a 70-mph outfit, form popular vantage points for the 3000 spectators that a typical club meet of local status draws.

One of the best-known courses was Brands Hatch, which used to be a counter-clockwise grass venue immediately after the Hitler war. It drew gates of 12,000. Now it is, of course, one of Europe’s finest clockwise road race circuits.

Some unknown names of those days were Jack Surtees (passenger John), Jock West (one-time sales director of AMC), Eric Oliver and Bill Boddice. Other grass notables since turf racing started in England in 1923 have been Eric Fernihough, Harold Taylor, Jack Williams (ex-AMC and Vincent development engineer) and Jack Booker (one-time sales manager of Royal Enfield).

Today’s courses are to be found throughout the breadth of the United Kingdom. For the March through October season, 65 events may be planned for a typical area by midwinter. Often more are added as the year advances.

At the premier meetings riders gain points toward the British Championships. And territorial representatives—England and Wales are split into 20 ACU Centers-also compete in a big national meeting at the end of the season.

A typical club program draws 110 soloists, some with as many as four bikes. There may be 50 sidecar outfits as well. Prize money is about $12 for a win and extends, on a diminishing scale, down only to 3rd place. For a recent national championship, top men Tony Black and Don Godden each took home some $60 prize money, about $15 more than an auto-mechanic’s weekly wages. Such remuneration is a once-a-year rarity. Out of it must come costs.

Entry fees for the one-day meet are $1 to $1.50, upped by 50 percent for a sidecar. This amount, which includes compulsory accident insurance, covers entry to all events in the afternoon’s program, which could run to 36 races.

Some classes require six heats plus semifinals, so large is the entry. Double entries, in two meets on the same day, me a scurvy trick to try to guarantee getting an entry accepted by at least one organizer. Such tactics are punished by suspension.

The number of starters in any one race is limited by the ACU, the governing body, and depends on track width, which must not be less than 25 ft. for four starters. One extra rider is permitted for each additional yard of width.

A typical field consists of 16 to 18 solos or 12 outfits. Race distance is rarely more than four miles, which explains the tiny gas tanks. A more typical distance is four laps for heats and six laps for finals, on one-halfto fiveeighths-mile circuits.

All solo events are ridden counter-clockwise, always and everywhere, which has resulted in a high degree of machine specialization. Neither converted roadsters nor scramblers steer well enough on the grass.

The finely developed broadsliding, in daylight in the open, is a good action spectacle and turf racing became a BBC television sport in 1966.

Sidehack crews ride the solo course, sometimes left-handed, sometimes right. Again, specialization has entered to the point that some riders will compete only on one type of course. Introduction of sidecar-only doglegs with a reverse bend have, to some extent, broken this paralyzing grip which so often prevented top crews ever coming into conflict.

Bitter and angry words have been spoken and written about this unsporting sidecar practice, but it persists. To some extent, clubs foster what riders started. It spoils a clean sport, yet it is defensible. Course specialists have developed outfits that go markedly well in one direction and which are hopelessly handicapped in the other. Can a local ace, confining himself to his own parish, be blamed for this?

Live engine starts are used, speedway style, generally from a rubber-band gate. With gas tanks cut to the bare minimum capacity, there can’t be-and isn’t-any hanging about under starter’s orders. Clutches wouldn’t last anyway!

On half-mile tracks the straights are short enough for an outside man, trying for a flyer round the perimeter, to be banked over all the way. Such courses are almost ellipses with generous bend radii, not always the same radius at each end. Double roping for spectator protection is used; cars parked at corners are set back an additional 12 ft., and on the straights, the cars can come closer.

Some tracks, like High Wycombe, Buckinghamshire, and the ever-popular Rhodes Minnis, have heavy gradients with maybe a tilt to the whole course of 5 ft. in 100, some of the up-grade perhaps concentrated into a short and stiff 1 ft. in 8 climb.

Apart from a spring cleaning in early March, the track receives little attention, so riders take bumps in their stride. Airborne wheels are commonplace and full suspension essential. But jumps of the scrambles typewith the whole bike well and truly in flightare quite unknown.

Surface varies from clean turf to gooey mud, according to weather and wear, just as a football field may change through a season. There are no groundsmen to chamfer it up. Sheep or cows, turned on it during the week as often as not, don’t crop it as nicely as a power mower!

Though a business-minded farmer makes more from renting a field to a club than he does from it by agriculture, he will still graze it if he can, so unwelcome moo-pats aren’t unknown in the paddock or the spectator areas.

There are no stands, no seats, precious little and dead primitive toilet facilities, and only mobile tea-wagons to cater for the inner man. But for the family, a warm, sunny day at a grass meeting makes a picnic a delight, with the taint of methanol and castor oil to flavor the sandwiches.

These, then are the courses. Some are operated for only a year, when the club has to find another field because of the plow. Tracks can be lapped at anything between 50 and 75 mph by 500-cc solos, and maximum speeds can be as high as 80 mph on the short straights.

What of the machines?

JAP (J.A. Prestwich)-powered specials top the bill. They are fast, accelerate well from low rpm, stay on tune and spares for them are plentiful and cheap. Consequently, capacity classes have not been bedeviled by the curious changes that are inflicted on British scrambling.

Events are divided into under 200 cc (less popular today and still basically a Triumph T20 category); 250 cc (dominated by the BSA Cl5 and various single-cylinder twostrokes, because the 250 JAP is a pathetic thing); 350 and 500 cc (JAP benefits), and unlimited (JAPs again). Chairs are invariably 650s (often Triumphs, but BSAs and occasionally Norton Twins also are raced). There are no Manx, 7R or G50 racers converted to the grass sport.

Technically, there is nothing much in the way of rules. The sport is free from restrictions on compression ratio, valve type, position, number or size (ditto carburetors), camshaft position or the number of cylinders.

Nevertheless, the JAP possesses the required attributes and seldom is challenged. Its virtues, according to Londoner Alf Hagon, now a top sprinter and once undisputed king of the turf until his recent retirement from that sport, are four-fold:

1. A good spread of power from 3000 to 7000 rpm-with 8000 on tap if W&S valve springs are installed.

2. Adequate top speed.

3. Stamina and reliability.

4. Quick to strip and rebuild.

Big-end life is mediocre, but cams, valves, barrels and pistons give no trouble on alcohol. The power characteristics and flywheel weight suit the job, as they do for speedway.

BSA Gold Stars have been tried but found lacking in mid-range response. A few Victors have recently made appearances and seem likely to stay. The Matchless G80 type is tolerable and, indeed, goes well when tuned by Jack Emmott, the ex-AMC raceshop mechanic who created the Matchmaker grass and speedway production special. Twins, for solo work, are out.

With methanol, the usual alcohol in use in England, the Cl5 comes into its own in the 250 class. A typical C15 would be set up with 10:1 compression ratio, and have a 1.469-in. inlet valve, scrambles cams and a 1.125-in. Monobloc with a 700 main jet. However, machines powered by Bultaco, Greeves, Husqvarna, Montesa and Ossa engines now make a powerful threat to the four-strokes.

Among the sidecars, 650s are supreme. They are generally iron-headed Triumphs with just one 389-series Amal road carburetor, running at 12:1 compression ratio on methanol. Mortality is high, so engines are timed for reliability, first, power second.

(Continued on page 82)

Continued from page 80

An iron BSA A10 with Spitfire cams, big inlet valves, 10:1 pistons, a single 1.187-in. Monobloc or a 1.25-in. Phillips injector gives a good account of itself. Gearboxes appropriate to the make are kept.

Solo cogging almost always comes from a four-speed Albion which is cheap, available and offered with a reasonable selection of internal ratios. Gearing for a 500 could be 19-tooth engine, 42-tooth clutch, 14-tooth gearbox and 40-tooth rearwheel sprocket.

Scrambles internals are the popular choice, but a rider on a shoestring budget can manage with road ones. AMC and Norton-Burman boxes also are used and occasionally the BSA. Three speeds are the very minimum except in the case of a 500 solo, which can get away with two because of its beefy torque.

Most variety comes in the cycle parts. Alf Hagon, unbeatable right up to his turf retirement, set the fashion. His own frame, a successor to the Kirby, is very widely used. Because it’s good it has been copied exactly. And it is often visibly the basis for many special builders’ creations.

Hagon, of course, is in the frame-building business, exporting to 23 countries. He founded his London shop at 350 High Road, Leytonstone, on his grass track name, about the only way his branch of motorcycle sport can be made to pay. His frames are worth describing, for they are representative of the best British practice.

Using the engine as a structural member, a single front down tube and a seat tube of 1.375 in. by 12 gauge is fusion-welded to a single top (or tank) tube of 1.375 in. by 14 gauge all in Reynolds A-quality mild steel. The swinging fork is of Sif-brazed 1.25-in. by 14-gauge T45 aircraft high-tensile round tube.

Wheelbase is about 57 in., head angle 69 degrees and trail (at full fork extension) 3.25 to 3.50 in. Hagon telescopic forks allow 4 in. of movement, controlled by a single, central damper and rubber bands. Rear Girlings of 3-in. stroke with 90to 100-lb. springs are specified.

Tires are generally Barum two-ply trialspattern tread, 2.75-21 or 2.75-23 front and 3.00 to 3.50-19 rear, according to rider, engine, and prejudice. Pressures are 15/16 psi front/rear-high because of the thin walls. Brakes are 5 and 7 in. in diameter, respectively.

The fuel tank holds 0.5 Imperial gal. and the bike, with fuel and oil, has a starting-grid weight of about 215 lb.

For sidehacks, a 50to 55-degree head angle is normal with trail cut down to reduce driver fatigue, handlebar shimmy on bumps being absorbed by telescopic hydraulic damping, usually either a Girling or Honda unit. Knobby tires on 16-in. rims are widely favored, and there is no third-wheel suspension.

Rigging is very taut and the front fork, inevitably homemade, must be strong. Main members can be 1.25-in. by 14-gauge T45. Plenty of handholds for the crewman are provided.

Speedway-style riding is the rule for the soloists. A steep head angle is needed to permit easy broadsliding, one reason why a scrambles or road bike, with a 65-degree head angle, does not handle properly on the turf. The actual angle is quite critical and should not be, according to Hagon, less than 68 nor more than 70 degrees.

With a steep head angle, the rider can enter a corner sideways, on full opposite lock, without the plot going down to the deck on him. Technique is to go in slightly slow and to gun out of the bend. Too much grip from the rear tire, for the engine’s power and the courses’s condition, prevents adequate wheel breakaway. Knobby back tires, desirable in some respects, let go too viciously on freshly -rained, hard courses.

Wheelbase is also important. Hagon recommends 57 in. Less makes a livelier bike, which can be a slim advantage on the damp grass of a smooth course, but if the course dries with clearing skies, this 2-in. shortness becomes a handicap.More wheelbase makes no difference and Hagon has found up to 60 in. to be quite all right.

Ground clearance must be 5 in. minimum if the crankcase is not to clout on bumps. Engine position is midway between wheels.

An interesting aspect about the wheels is the need for two security bolts at the back and one at the front, with the bolt on the front wheel employed to stop tire creep in the opposite direction to that of the rear wheel.

While brakes are obligatory, many soloists ride brakeless; another large slice use only the back anchor; and* only a few experts can handle a front stopper properly.

But grassing is not an experts-only sport. It is very much fun for the lads, and one of the few remaining branches of the British motorcycle game in which the boys-without whom no race would be a race—can have a real go at minimal expense.

Like sprinting, it has an informal atmosphere, very far removed from highly financed road racing, now Big Business at Stock Exchange level in England.