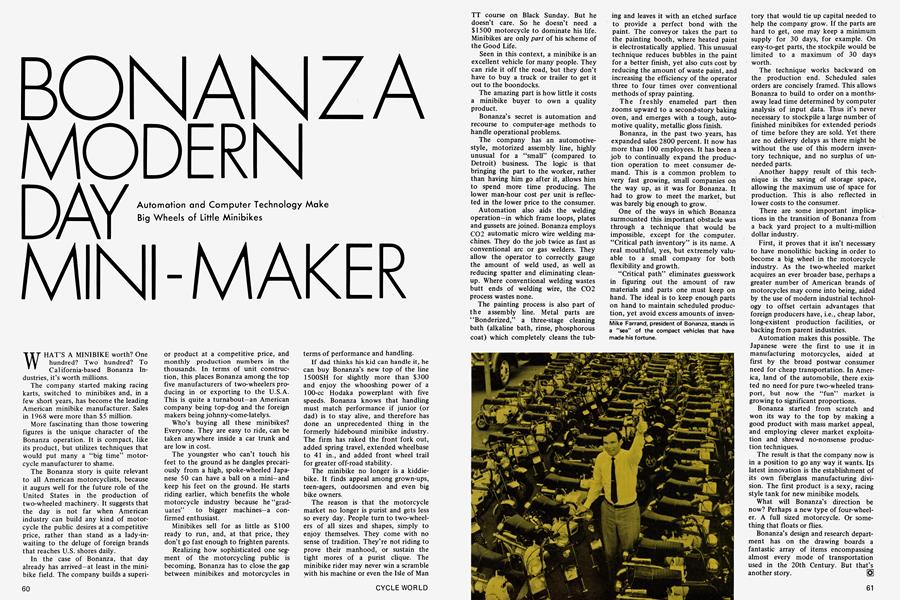

BONANZA MODERN DAY MINI-MAKER

Automation and Computer Technology Make Big Wheels of Little Minibikes

WHAT’S A MINIBIKE worth? One hundred? Two hundred? To California-based Bonanza Industries, it’s worth millions.

The company started making racing karts, switched to minibikes and, in a few short years, has become the leading American minibike manufacturer. Sales in 1968 were more than $5 million.

More fascinating than those towering figures is the unique character of the Bonanza operation. It is compact, like its product, but utilizes techniques that would put many a “big time” motorcycle manufacturer to shame.

The Bonanza story is quite relevant to all American motorcyclists, because it augurs well for the future role of the United States in the production of two-wheeled machinery. It suggests that the day is not far when American industry can build any kind of motorcycle the public desires at a competitive price, rather than stand as a lady-inwaiting to the deluge of foreign brands that reaches U.S. shores daily.

In the case of Bonanza, that day already has arrived-at least in the minibike field. The company builds a superior product at a competitive price, and monthly production numbers in the thousands. In terms of unit construction, this places Bonanza among the top five manufacturers of two-wheelers producing in or exporting to the U.S.A. This is quite a turnabout—an American company being top-dog and the foreign makers being johnny-come-latelys.

Who’s buying all these minibikes? Everyone. They are easy to ride, can be taken anywhere inside a car trunk and are low in cost.

The youngster who can’t touch his feet to the ground as he dangles precariously from a high, spoke-wheeled Japanese 50 can have a ball on a mini-and keep his feet on the ground. He starts riding earlier, which benefits the whole motorcycle industry because he “graduates” to bigger machines—a confirmed enthusiast.

Minibikes sell for as little as $100 ready to run, and, at that price, they don’t go fast enough to frighten parents.

Realizing how sophisticated one segment of the motorcycling public is becoming, Bonanza has to close the gap between minibikes and motorcycles in terms of performance and handling.

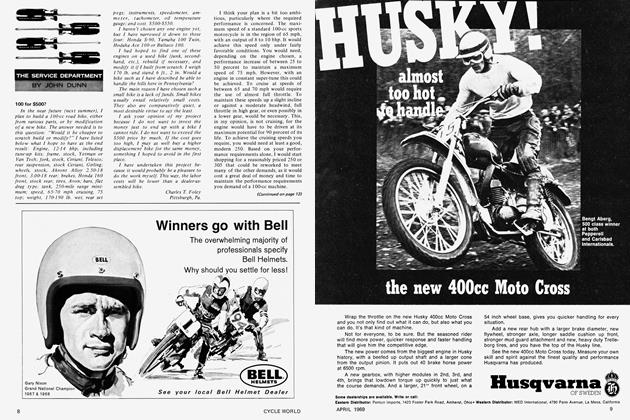

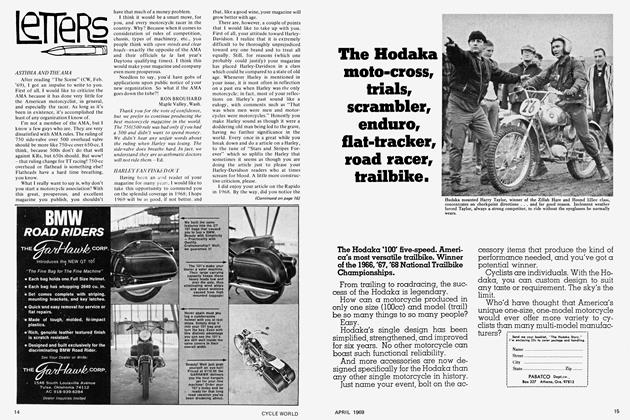

If dad thinks his kid can handle it, he can buy Bonanza’s new top of the line 1500SH for slightly more than $300 and enjoy the whooshing power of a 100-cc Hodaka powerplant with five speeds. Bonanza knows that handling must match performance if junior (or dad) is to stay alive, and therefore has done an unprecedented thing in the formerly hidebound minibike industry. The firm has raked the front fork out, added spring travel, extended wheelbase to 41 in., and added front wheel trail for greater off-road stability.

The minibike no longer is a kiddiebike. It finds appeal among grown-ups, teen-agers, outdoorsmen and even big bike owners.

The reason is that the motorcycle market no longer is purist and gets less so every day. People turn to two-wheelers of all sizes and shapes, simply to enjoy themselves. They come with no sense of tradition. They’re not riding to prove their manhood, or sustain the tight mores of a purist clique. The minibike rider may never win a scramble with his machine or even the Isle of Man TT course on Black Sunday. But he doesn’t care. So he doesn’t need a $1500 motorcycle to dominate his life. Minibikes are only part of his scheme of the Good Life.

Seen in this context, a minibike is an excellent vehicle for many people. They can ride it off the road, but they don’t have to buy a truck or trailer to get it out to the boondocks.

The amazing part is how little it costs a minibike buyer to own a quality product.

Bonanza’s secret is automation and recourse to computer-age methods to handle operational problems.

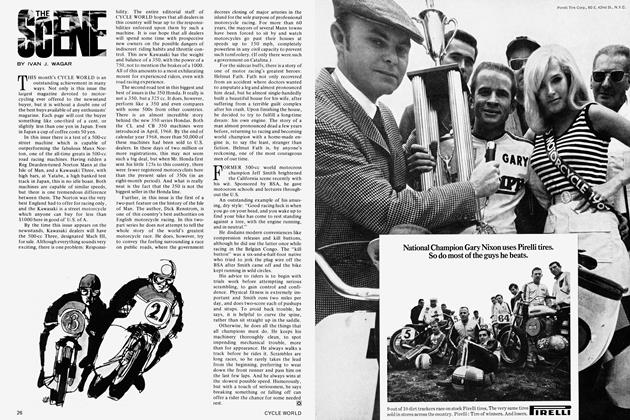

The company has an automotivestyle, motorized assembly line, highly unusual for a “small” (compared to Detroit) business. The logic is that bringing the part to the worker, rather than having him go after it, allows him to spend more time producing. The lower man-hour cost per unit is reflected in the lower price to the consumer.

Automation also aids the welding operation—in which frame loops, plates and gussets are joined. Bonanza employs CO2 automatic micro wire welding machines. They do the job twice as fast as conventional arc or gas welders. They allow the operator to correctly gauge the amount of weld used, as well as reducing spatter and eliminating cleanup. Where conventional welding wastes butt ends of welding wire, the C02 process wastes none.

The painting process is also part of the assembly line. Metal parts are “Bonderized,” a three-stage cleaning bath (alkaline bath, rinse, phosphorous coat) which completely cleans the tubing and leaves it with an etched surface to provide a perfect bond with the paint. The conveyor takes the part to the painting booth, where heated paint is electrostatically applied. This unusual technique reduces bubbles in the paint for a better finish, yet also cuts cost by reducing the amount of waste paint, and increasing the efficiency of the operator three to four times over conventional methods of spray painting.

The freshly enameled part then zooms upward to a second-story baking oven, and emerges with a tough, automotive quality, metallic gloss finish.

Bonanza, in the past two years, has expanded sales 2800 percent. It now has more than 100 employees. It has been a job to continually expand the production operation to meet consumer demand. This is a common problem to very fast growing, small companies on the way up, as it was for Bonanza. It had to grow to meet the market, but was barely big enough to grow.

One of the ways in which Bonanza surmounted this important obstacle was through a technique that would be impossible, except for the computer. “Critical path inventory” is its name. A real mouthful, yes, but extremely valuable to a small company for both flexibility and growth.

“Critical path” eliminates guesswork in figuring out the amount of raw materials and parts one must keep on hand. The ideal is to keep enough parts on hand to maintain scheduled production, yet avoid excess amounts of inventory that would tie up capital needed to help the company grow. If the parts are hard to get, one may keep a minimum supply for 30 days, for example. On easy-to-get parts, the stockpile would be limited to a maximum of 30 days worth.

The technique works backward on the production end. Scheduled sales orders are concisely framed. This allows Bonanza to build to order on a monthsaway lead time determined by computer analysis of input data. Thus it’s never necessary to stockpile a large number of finished minibikes for extended periods of time before they are sold. Yet there are no delivery delays as there might be without the use of this modern inventory technique, and no surplus of unneeded parts.

Another happy result of this technique is the saving of storage space, allowing the maximum use of space for production. This is also reflected in lower costs to the consumer.

There are some important implications in the transition of Bonanza from a back yard project to a multi-million dollar industry.

First, it proves that it isn’t necessary to have monolithic backing in order to become a big wheel in the motorcycle industry. As the two-wheeled market acquires an ever broader base, perhaps a greater number of American brands of motorcycles may come into being, aided by the use of modern industrial technology to offset certain advantages that foreign producers have, i.e., cheap labor, long-existent production facilities, or backing from parent industries.

Automation makes this possible. The Japanese were the first to use it in manufacturing motorcycles, aided at first by the broad postwar consumer need for cheap transportation. In America, land of the automobile, there existed no need for pure two-wheeled transport, but now the “fun” market is growing to significant proportions.

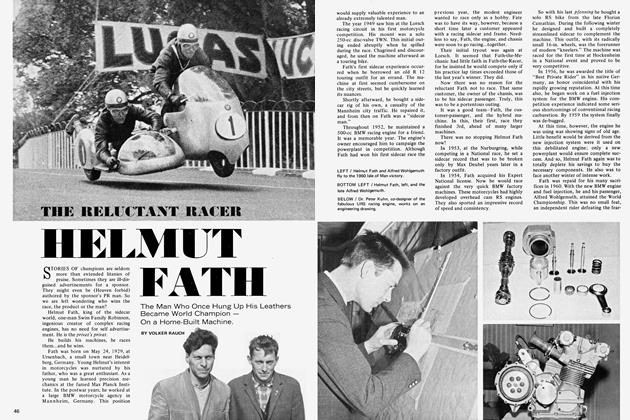

Bonanza started from scratch and won its way to the top by making a good product with mass market appeal, and employing clever market exploitation and shrewd no-nonsense production techniques.

The result is that the company now is in a position to go any way it wants. Its latest innovation is the establishment of its own fiberglass manufacturing division. The first product is a sexy, racing style tank for new minibike models.

What will Bonanza’s direction be now? Perhaps a new type of four-wheeler. A full sized motorcycle. Or something that floats or flies.

Bonanza’s design and research department has on the drawing boards a fantastic array of items encompassing almost every mode of transportation used in the 20th Century. But that’s another story.