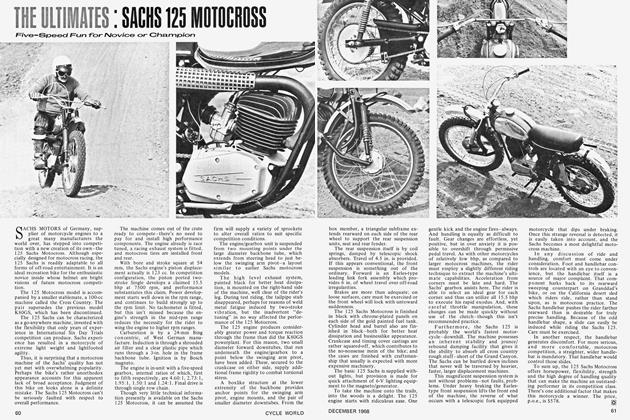

Motorcycles Do Compute

They all compete in the Punch Card Grand Prix....

HENRY A. WATTS

EVERY time I read a CYCLE WORLD Road Test and look over the specification sheet I find myself getting a bit lost. Here’s a 305 with 36.2 sq. in. of brake swept area. Is that good? Here’s a 750 with only 30 sq. in. Is that bad? Here’s a 650 that does the quarter mile in 15.4 sec. Is that fast? Slow? I finally got so frustrated that I decided to set up some charts and find out what ranked how. The motorcycles I chose, from among four years of CYCLE WORLD Road Tests, are street machines, partly because that’s what I am interested in, and partly because the specifications available in the Road Tests seem to be more relevant to street riding than to any of the non-street uses, such as trials, trail, enduro, or road racing. There were 67 bikes in all, chosen from the CYCLE WORLD Road Tests from January, 1964, through March, 1968. A computer was used to do a proper job.

The computer was an IBM 1130 with a double-sized (eight hex) core. The computer was fed the name of each bike selected, its displacement, number of cycles, number of cylinders, the year it was reviewed, the manufacturer’s claimed horsepower, the number of carburetors, the compression ratio, the test results for quarter-mile elapsed time, 0-60 mph elapsed time, and practical top speed; the weight, seat height, wheelbase, brake swept area, numbers of gears and price also were fed in for the 67 machines. The computer calculated ratios, claimed horsepower to weight, claimed bhp per cc of piston displacement, brake swept area to weight, price per claimed bhp. and price per lb. It then adjusted the weight of the bike upward to account for a 175-lb. rider and recalculated the claimed bhp/weight ratio (a reasonable index of how well the machine should accelerate after corrections for numbers of gears and gearing ratios are made) and the brake swept area to weight ratio. It quickly became clear that I could have profited from more extensive and less ambiguous data. Earlier tests on some machines were not complete.

It must be kept firmly in mind that CYCLE WORLD tests only one bike as representative of the many that are produced. All manufacturers produce some variation within the range of quality which they set for themselves, and it may make a great deal of difference whether the machine that is placed in the hands of the tester is perfect or just good. Nevertheless, the Road Tests, while being far from perfect, are the best data available, and have the tremendous advantage of being free from the whims of an overzealous distributor who may be running his performance tests with a 70-lb. midget in the saddle. Thus, I simply accepted the Road Tests as being the best data available.

The motorcycles included in this program were to be street machines of 150 cc piston displacement or more. The displacement is easy enough to determine, but it is not always clear just whether or not a bike is a street machine. I adopted the criterion that anything with street-legal lighting would be included. This eliminated the machines wliich were designed purely to eat up mountains and swamps, but left some rather radical racing gear in the sample. The wildest of these was probably the Dunstall Norton 750; anyone who starts with a rather fast 750, and strips it down to 368 lb. with a respectable 62 bhp and fairing has created a distinct brand of street riding. The bike is available for purchase, however, and it certainly does have street-legal lighting, so it was retained in the sample. Where CYCLE WORLD has run more than one test on a particular machine (Harley-Davidson FLH and the BSA Spitfire series, for example), each test was included as a separate machine.

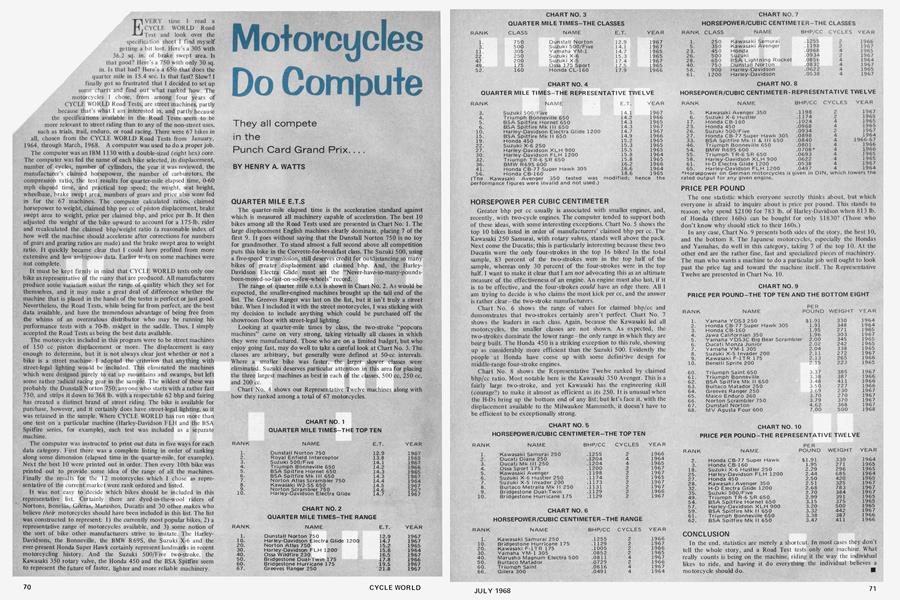

The computer was instructed to print out data in five ways for each data category, hirst there was a complete listing in order of ranking along some dimension (elapsed time in the quarter-mile, for example). Next the best 10 were printed out in order. Then every 10th bike was printed out to provide some idea of the range of all the machines, f inally the results for the 12 motorcycles which I chose as representative of the current market were rank ordered and listed.

It was not easy to decide which bikes should be included in this representative list. Certainly there are dyed-in-the-wool riders of Nortons, Benellis. Güeras, Marushos, Ducatis and 30 other makes who believe their motorcycles should have been included in this list. The list was constructed to represent: 1) the currently most popular bikes, 2) a representative range of motorcycles available, and 3) some notion of the sort of bike other manufacturers strive to imitate. The HarleyDavidsons, the Bonnevüle. the BMW R69S, the Suzuki X-6 and the ever-present Honda Super Hawk certainly represent landmarks in recent motorcycling history. And the Suzuki 500/Five two-stroke, the Kawasaki 350 rotary valve, the Honda 450 and the BSA Spitfire seem to represent the future of faster, lighter and more reliable machinery.

QUARTER MILE E.T.S

The quarter-mile elapsed time is the acceleration standard against wliich is measured all machinery capable of acceleration. The best 10 bikes among all the Road Tests used are presented in Chart No. 1. The large displacement English machines clearly dominate, placing 7 of the first 9. It goes without saying that the Dunstall Norton 750 is no toy for grandmother. To stand almost a full second above all competition puts this bike in the Corvette-for-breakfast class. The Suzuki 500, using a five-speed transmission, still deserves credit for outdistancing so many bikes of greater displacement and claimed bhp. And, the HarleyDavidson Electra Glide must set the “Never-have-so-many-poundsbeen-moved-so-fast-on-so-few-wheels” record.

The range of quarter mile e.t.s is shown in Chart No. 2. As would be expected, the smaller-cngined machines brought up the tail end of the List. The Greeves Ranger was last on the list, but it isn’t truly a street bike. When I included it with the street motorcycles, I was sticking with my decision to include anything which could be purchased off the showroom Hoor with street-legal lighting.

Looking at quarter-müe times by class, the two-stroke “popcorn machines” came on very strong, taking virtually all classes in which they were manufactured. Those who are on a limited budget, but who enjoy going fast, may do well to take a careful look at Chart No. 3. The classes are arbitrary, but generally were defined at 50-cc intervals. Where a smaller bike was faster, the larger slower classes were eliminated. Suzuki deserves particular attention in this area for placing the three largest machines as best in each of the classes, 500 cc, 250 cc, and 200 cc.

Chart No. 4 shows our Representative Twelve machines along with how they ranked among a total of 67 motorcycles.

CHART NO. 1

CHART NO. 2

CHART NO. 3

CHART NO. 4

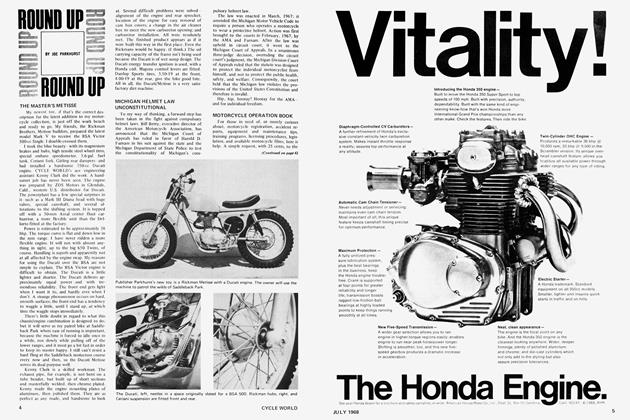

HORSEPOWER PER CUBIC CENTIMETER

Greater bhp per cc usually is associated with smaller engines, and, recently, with two-cycle engines. The computer tended to support both of these ideas, with some interesting exceptions. Chart No. 5 shows the top 10 bikes listed in order of manufacturers’ claimed bhp per cc. The Kawasaki 250 Samurai, with rotary valves, stands well above the pack. Next come the Ducatis; this is particularly interesting because these two Ducatis were the only four-strokes in the top 16 bikes! In the total sample, 83 percent of the two-strokes were in the top half of the sample, whereas only 30 percent of the four-strokes were in the top half. I want to make it clear that 1 am not advocating this as an ultimate measure of the effectiveness of an engine. An engine must also last, if it is to be effective, and the four-strokes could have an edge there. All 1 am trying to decide is who claims the most kick per cc, and the answer is rather clear-the two-stroke manufacturers.

(’hart No. 6 shows the range of values for claimed bhp/cc and demonstrates that two-strokes certainly aren't perfect. Chart No. 7 shows the leaders in each class. Again, because the Kawasaki led all motorcycles, the smaller classes are not shown. As expected, the two-strokes dominate the lower range the only range in which they are being built. The Honda 450 is a striking exception to this rule, showing up as considerably more efficient than the Suzuki 500. Evidently the people at Honda have come up with some definitive design for middle-range four-stroke engines.

Chart No. 8 shows the Representative Twelve ranked by claimed bhp/cc ratio. Most notable here is the Kawasaki 350 Avenger. This is a fairly large twostroke, and yet Kawasaki has the engineering skill (courage?) to make it almost as efficient as its 250. It is unusual when the H-Ds bring up the bottom end of any list; but let’s face it, with the displacement available to the Milwaukee Mammoth, it doesn’t have to be efficient to be exceptionally strong.

CHART NO. 5

CHART NO. 6

CHART NO. 7

CHART NO. 8

PRICE PER POUND

The one statistic which everyone secretly thinks about. but which everyone is afraid to inquire about is price per pound. T his stands to reason; why spend $2100 for 783 lb. of Harley-Davidson when 813 lb. of Honda (three 160s) can be bought for only $1830? (Those who don’t know why should stick to their 160s.)

In any case, Chart No. 9 presents both sides of the story, the best 10, and the bottom 8. The Japanese motorcycles, especially the Hondas and Yamahas, do well in this category, taking 7 of the top 10. At the other end are the rather fine, fast and specialized pieces of machinery. The man who wants a machine to do a particular job well ought to look past the price tag and toward the machine itself. The Representative Twelve are presented in Chart No. 10.

CHART NO. 9

CHART NO. 10

CONCLUSION

In the end, statistics are merely a shortcut. In most cases they don’t tell the whole story, and a Road Tes t tests only one machine. What really counts is being on the machine, riding it the way the individual likes to ride, and having it do everything the individual believes a motorcycle should do. B