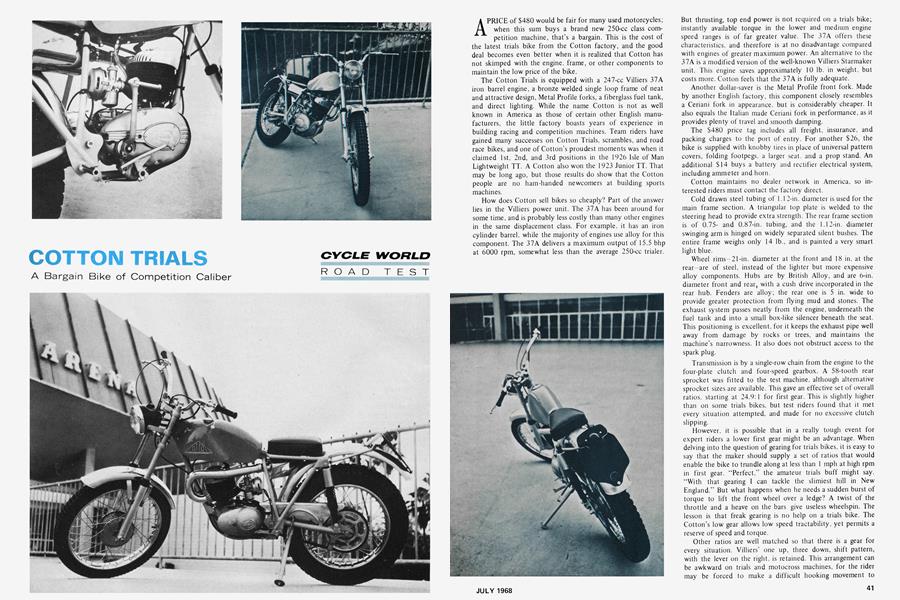

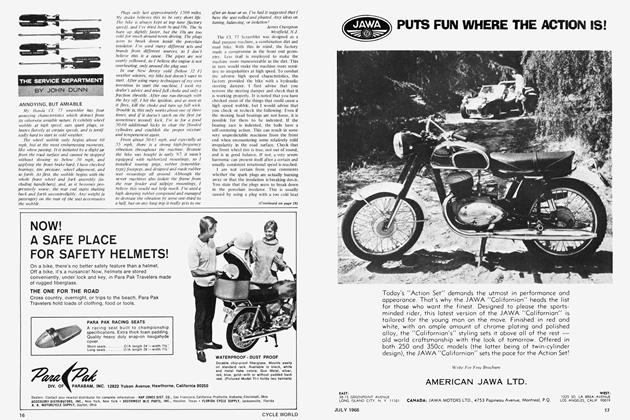

COTTON TRIALS

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

A Bargain Bike of Competition Caliber

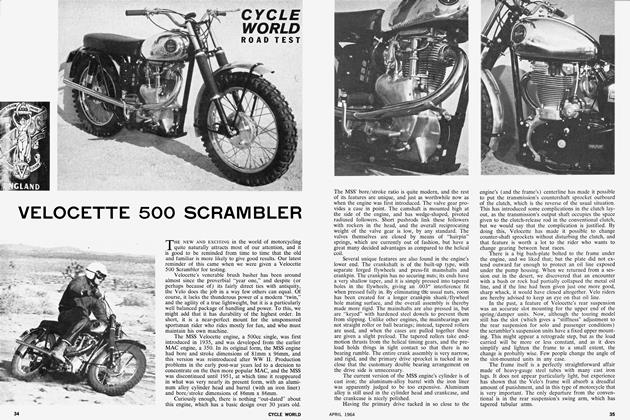

A PRICE of $480 would be fair for many used motorcycles; when this sum buys a brand new 250-cc class competition machine, that’s a bargain. This is the cost of the latest trials bike from the Cotton factory, and the good deal becomes even better when it is realized that Cotton has not skimped with the engine, frame, or other components to maintain the low price of the bike.

The Cotton Trials is equipped with a 247-cc Villiers 37A iron barrel engine, a bronze welded single loop frame of neat and attractive design, Metal Profile forks, a fiberglass fuel tank, and direct lighting. While the name Cotton is not as well known in America as those of certain other English manufacturers, the little factory boasts years of experience in building racing and competition machines. Team riders have gained many successes on Cotton Trials, scrambles, and road race bikes, and one of Cotton’s proudest moments was when it claimed 1st, 2nd, and 3rd positions in the 1926 Isle of Man Lightweight TT. A Cotton also won the 1923 Junior TT. That may be long ago, but those results do show that the Cotton people are no ham-handed newcomers at building sports machines.

How does Cotton sell bikes so cheaply? Part of the answer lies in the Villiers power unit. The 37A has been around for some time, and is probably less costly than many other engines in the same displacement class. For example, it has an iron cylinder barrel, while the majority of engines use alloy for this component. The 37A delivers a maximum output of 15.5 bhp at 6000 rpm, somewhat less than the average 250-cc trialer. But thrusting, top end power is not required on a trials bike; instantly available torque in the lower and medium engine speed ranges is of far greater value. The 37A offers these characteristics, and therefore is at no disadvantage compared with engines of greater maximum power. An alternative to the 37A is a modified version of the well-known Villiers Starmaker unit. This engine saves approximately 10 lb. in weight, but costs more. Cotton feels that the 37A is fully adequate.

Another dollar-saver is the Metal Profile front lork. Made by another English factory, this component closely resembles a Ceriani fork in appearance, but is considerably cheaper. It also equals the Italian made Ceriani fork in performance, as it provides plenty of travel and smooth damping.

The $480 price tag includes all freight, insurance, and packing charges to the port of entry. For another $26, the bike is supplied with knobby tires in place of universal pattern covers, folding footpegs, a larger seat, and a prop stand. An additional $14 buys a battery and rectifier electrical system, including ammeter and horn.

Cotton maintains no dealer network in America, so interested riders must contact the factory direct.

Cold drawn steel tubing of 1.1 2-in. diameter is used for the main frame section. A triangular top plate is welded to the steering head to provide extra strength. The rear frame section is of Ü.75and 0.87-in. tubing, and the 1.12-in. diameter swinging arm is hinged on widely separated silent bushes. The entire frame weighs only 14 lb., and is painted a very smart light blue.

Wheel rims-21-in. diameter at the front and 18 in. at the rear-are of steel, instead of the lighter but more expensive alloy components. Hubs are by British Alloy, and are 6-in. diameter front and rear, with a cush drive incorporated in the rear hub. Fenders are alloy; the rear one is 5 in. wide to provide greater protection from flying mud and stones. The exhaust system passes neatly from the engine, underneath the fuel tank and into a small box-like silencer beneath the seat. This positioning is excellent, for it keeps the exhaust pipe well away from damage by rocks or trees, and maintains the machine’s narrowness. It also does not obstruct access to the spark plug.

Transmission is by a single-row chain from the engine to the four-plate clutch and four-speed gearbox. A 58-tooth rear sprocket was fitted to the test machine, although alternative sprocket sizes are available. This gave an effective set of overall ratios, starting at 24.9:1 for first gear. This is slightly higher than on some trials bikes, but test riders found that it met every situation attempted, and made for no excessive clutch slipping.

However, it is possible that in a really tough event tor expert riders a lower first gear might be an advantage. When delving into the question of gearing for trials bikes, it is easy to say that the maker should supply a set of ratios that would enable the bike to trundle along at less than 1 mph at high rpm in first gear. “Perfect.” the amateur trials buff might say. “With that gearing 1 can tackle the slimiest hill in New England.” But what happens when he needs a sudden burst of torque to lift the front wheel over a ledge? A twist of the throttle and a heave on the bars give useless wheelspin. The lesson is that freak gearing is no help on a trials bike. The Cotton’s low gear allows low speed tractability. yet permits a reserve of speed and torque.

Other ratios are well matched so that there is a gear for every situation. Villiers' one up, three down, shift pattern, with the lever on the right, is retained. This arrangement can be awkward on trials and motocross machines, for the rider may be forced to make a difficult hooking movement to change down, while at the same time he stands on the footpegs, avoids overhanging tree branches, picks a path between bone-jarring rocks, and spots the course surface that provides the greatest traction. Anything which makes his task less hectic is more than welcome! On the Cotton, this is achieved by the use of a gear pedal with a short rearward extension, so that the toe can simply press down on the pedal to make a downshift.

The 37A engine generates an abundance of low-speed pulling power, and delivers instant response to the twistgrip under all conditions. A previous test of the Cotton (CW, April ’67) complained about poor starting and the high level of noise. The noise remains undiminished by an inadequate silencer, but starting is easier. The complaint here was that the lever was badly positioned, and could not be swung through without hitting the footpeg. Location of these parts has not been altered, yet the latest bike usually starts after only one prod at the lever.

Total weight of the Cotton, ready for action with a half-tank of fuel, lighting system and prop stand, is a lissome 222.5 lb., fully in line with its more expensive competitors. This modest bulk, coupled with its extreme slenderness, makes the Cotton easily maneuverable. Switching the bike from one side to the other to gain maximum benefit«, from body lean requires no great effort. However, a little more steering lock would be useful. There were really tight situations in which greater turning ability was required. At such times the bike tended to “crab” forward when throttle was applied.

Ground clearance of 10 in. is sufficient to allow trouble free passage over most of the logs and rocks that litter trials sections. Both brakes are adequate for the newcomer to trials, they are powerful yet sensitive. But the expert rider might prefer the cable-operated rear brake to be converted to rod operation. This would give that little extra degree of control that on a greasy downhill camber could mean the difference between a clean and a dab.

Riding position on a trials bike is vitally important for good results. The trials man spends a greater percentage of his competition time standing on the footpegs than any other rider, including the motocross racer. Virtually every section demands that he must stand up and be ready to shift his weight exactly where it is needed at an instant’s notice. Thus the relationship between handlebar, seat and footpegs is the deciding factor in rider comfort.

On the Cotton, the footpegs are set high, to provide as much ground clearance as possible. But the steering head is also high, and combined with a rather Hat handlebar offers a comfortable position, with the rider neither stooping nor over-reaching. The footpegs are set well rearward and are drilled for lightness, and braced with flat strips welded to the tops for easy-to-grip surfaces. They are bolted into bosses on the rear frame tubes. The left footpeg also is the pivot point for the rear brake pedal. The seat is very tiny, but is comfortable during a trial. Obviously, it has not been designed for long trips. It fits into the Cotton’s image as a trials bike, rather than a trail mount.

Bargains from Cotton do not end at the Trials bike. The firm also sells the Cotton Cossack Scrambler, equipped with a Metal Profile front fork, for S606, or with Ceriani fork, for $630. By reason of the absence of Cotton dealers in America, customers send checks direct to the factory when buying machines. This may seem a risky method of conducting a deal, but Cotton’s managing director. Monty Denley, has a file of letters from U.S. customers who have “bought blind” and been fully satisfied with their machines and Cotton’s financial arrangements. ■

COTTON

TRIALS

$480