AQUAPLANING

JACK WOODS

EXACTLY HOW MANY motorcyclists have lost control of their machines and crashed at high speed because of aquaplaning will never be known; but in the light of recent research, it would seem very likely that many such accidents — often vaguely attributed to misadventures or lack of riding experience — were, in fact, due to the aquaplaning phenomenon, something which can take even seasoned riders by surprise while riding in the rain, especially in heavy rain on a road surface with poor drainage.

The multiple spills on the first lap of the 1966 Belgium Grand Prix at Spa provide a good example of this. While the fact that so many crack racing men, including both the late Bob McIntyre and Dickie Dale, have crashed fatally while competing in bad weather is not without some significance. Generally speaking, a motorcycle is slower to aquaplane than an automobile, because its front tire has a relatively smaller footprint on the road. This reduces the physical distance over w'hich the water escaping from the contact area has to travel, and by this easier drainage, makes it difficult for a wedge of water to build up under the tire tread. When this occurs, the tire loses contact with the road, becoming completely waterborne and able to slide along the road on this water-wedge with resultant loss of steering and front brake control.

This is known as aquaplaning. Although full aquaplaning of the type just described can have disastrous consequences because of the high speed required for its generation, it is unusual and not nearly as common as semi-aquaplaning, since although it requires an excellent combination of speed and water to make a good tire aquaplane, a badly w'orn tire will easily enter a state of semi-aquaplaning without the rider being aware of it. It will give sufficient grip for careful riding, but not enough safety margin to cope with a sudden maneuver, either by the rider or by other traffic on the road. When this happens it can make the rider suddenly and painfully aware that he has been virtually riding on a tightrope.

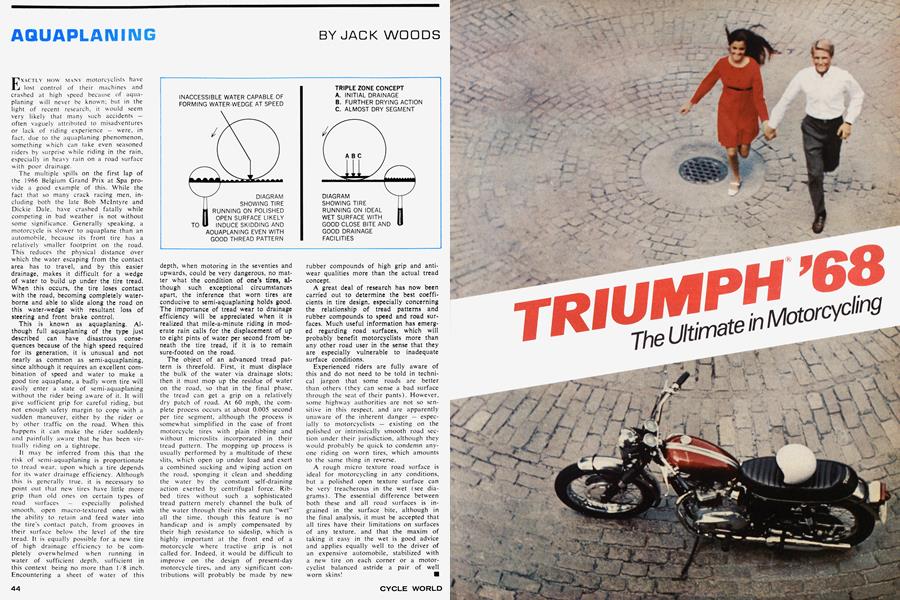

It may be inferred from this that the risk of semi-aquaplaning is proportionate to tread wear, upon which a tire depends for its water drainage efficiency. Although this is generally true, it is necessary to point out that new tires have little more grip than old ones on certain types of road surfaces — especially polished smooth, open macro-textured ones with the ability to retain and feed water into the tire’s contact patch, from grooves in their surface below the level of the tire tread. It is equally possible for a new' tire of high drainage efficiency to be completely overwhelmed when running in w'ater of sufficient depth, sufficient in this context being no more than 1/8 inch. Encountering a sheet of water of this depth, when motoring in the seventies and upwards, could be very dangerous, no matter what the condition of one’s tires, although such exceptional circumstances apart, the inference that worn tires are conducive to semi-aquaplaning holds good. The importance of tread wear to drainage efficiency will be appreciated when it is realized that mile-a-minute riding in moderate rain calls for the displacement of up to eight pints of water per second from beneath the tire tread, if it is to remain sure-footed on the road.

The object of an advanced tread pattern is threefold. First, it must displace the bulk of the w'ater via drainage slots; then it must mop up the residue of water on the road, so that in the final phase, the tread can get a grip on a relatively dry patch of road. At 60 mph, the complete process occurs at about 0.005 second per tire segment, although the process is somewhat simplified in the case of front motorcycle tires w'ith plain ribbing and without microslits incorporated in their tread pattern. The mopping up process is usually performed by a multitude of these slits, which open up under load and exert a combined sucking and wiping action on the road, sponging it clean and shedding the water by the constant self-draining action exerted by centrifugal force. Ribbed tires without such a sophisticated tread pattern merely channel the bulk of the w'ater through their ribs and run “wet” all the time, though this feature is no handicap and is amply compensated by their high resistance to sideslip, which is highly important at the front end of a motorcycle where tractive grip is not called for. Indeed, it would be difficult to improve on the design of present-day motorcycle tires, and any significant contributions will probably be made by new

rubber compounds of high grip and antiwear qualities more than the actual tread concept.

A great deal of research has now been carried out to determine the best coefficients in tire design, especially concerning the relationship of tread patterns and rubber compounds to speed and road surfaces. Much useful information has emerged regarding road surfaces, which will probably benefit motorcyclists more than any other road user in the sense that they are especially vulnerable to inadequate surface conditions.

Experienced riders are fully aware of this and do not need to be told in technical jargon that some roads are better than others (they can sense a bad surface through the seat of their pants). However, some highway authorities are not so sensitive in this respect, and are apparently unaware of the inherent danger — especially to motorcyclists — existing on the polished or intrinsically smooth road section under their jurisdiction, although they would probably be quick to condemn anyone riding on worn tires, which amounts to the same thing in reverse.

A rough micro texture road surface is ideal for motorcycling in any conditions, but a polished open texture surface can be very treacherous in the wet (see diagrams). The essential difference between both these and all road surfaces is ingrained in the surface bite, although in the final analysis, it must be accepted that all tires have their limitations on surfaces of any texture, and that the maxim of taking it easy in the wet is good advice and applies equally well to the driver of an expensive automobile, stabilized with a new' tire on each corner or a motorcyclist balanced astride a pair of well worn skins! M