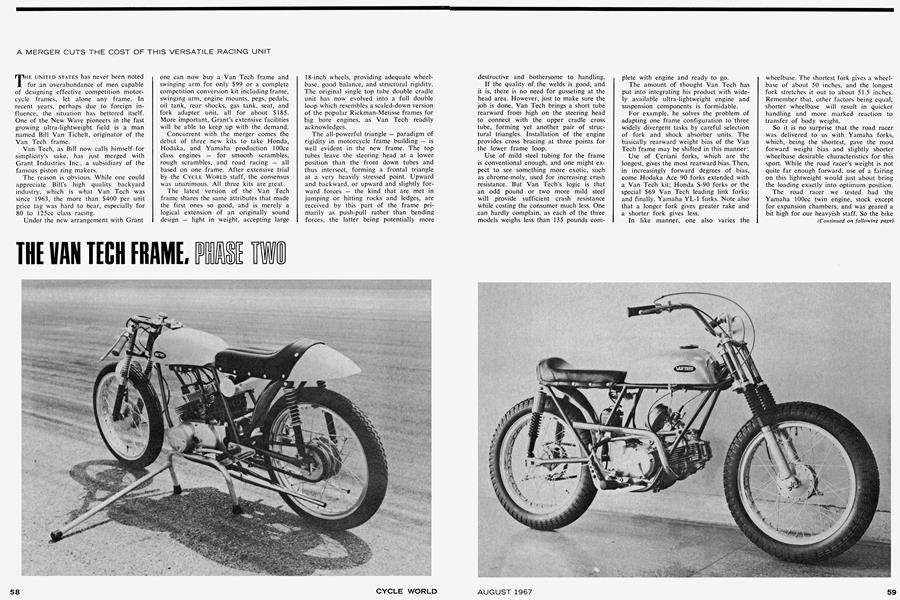

THE VAN TECH FRAME, PHASE TWO

A MERGER CUTS THE COST OF THIS VERSATILE RACING UNIT

THE UNITED STATES has never been noted for an overabundance of men capable of designing effective competition motor-cycle frames, let alone any frame. In recent years, perhaps due to foreign influence, the situation has bettered itself. One of the New Wave pioneers in the fast growing ultra-lightweight field is a man named Bill Van Tichelt, originator of the Van Tech frame.

Van Tech, as Bill now calls himself for simplicity's sake, has just merged with Grant Industries Inc., a subsidiary of the famous piston ring makers.

The reason is obvious. While one could appreciate Bill's high quality backyard industry, which is what Van Tech was since 1963, the more than $400 per unit price tag was hard to bear, especially for 80 to 125cc class racing.

Under the new arrangement with Grant

one can now buy a Van Tech frame and swinging arm for only $99 or a complete competition conversion kit including frame, swinging arm, engine mounts, pegs, pedals, oil tank, rear shocks, gas tank, seat, and fork adapter unit, all for about $185. More important, Grant's extensive facilities will be able to keep up with the demand.

Concurrent with the merger comes the debut of three new kits to take Honda, Hodaka, and Yamaha production 100cc class engines - for smooth scrambles, rough scrambles, and road racing - all based on one frame. After extensive trial by the CYCLE WORLD staff, the consensus was unanimous. All three kits are great.

The latest version of the Van Tech frame shares the same attributes that made the first ones so good, and is merely a logical extension of an originally sound design - light in weight, accepting large

18-inch wheels, providing adequate wheel base, good balance, and structural rigidity. The original single top tube double cradle unit has now evolved into a full double loop which resembles a scaled-down version of the popular Rickman-Metisse frames for big bore engines, as Van Tech readily acknowledges.

The all-powerful triangle - paradigm of rigidity in motorcycle frame building - is well evident in the new frame. The top tubes leave the steering head at a lower position than the front down tubes and thus intersect, forming a frontal triangle at a very heavily stressed point. Upward and backward, or upward and slightly for ward forces - the kind that are met in jumping or hitting rocks and ledges, are received by this part of the frame pri marily as push-pull rather than bending forces, the latter being potentially more destructive and bothersome to handling.

If the quality of the welds is good, and it is, there is no need for gusseting at the head area. However, just to make sure the job is done, Van Tech brings a short tube rearward from high on the steering head to connect with the upper cradle cross tube, forming yet another pair of structural triangles. Installation of the engine provides cross bracing at three points for the lower frame loop.

Use of mild steel tubing for the frame is conventional enough, and one might expect to see something more exotic, such as chrome-moly, used for increasing crash resistance. But Van Tech's logic is that an odd pound or two more mild steel will provide sufficient crash resistance while costing the consumer much less. One can hardly complain, as each of the three models weighs less than 135 pounds complete with engine and ready to go.

The amount of thought Van Tech has put into integrating his product with widely available ultra-lightweight engine and suspension components is formidable.

For example, he solves the problem of adapting one frame configuration to three widely divergent tasks by careful selection of fork and shock absorber units. The basically rearward weight bias of the Van Tech frame may be shifted in this manner: Use of Ceriani forks, which are the longest, gives the most rearward bias. Then, in increasingly forward degrees of bias, come Hodaka Ace 90 forks extended with a Van Tech kit; Honda S-90 forks or the special $69 Van Tech leading link forks; and finally, Yamaha YL-1 forks. Note also that a longer fork gives greater rake and a shorter fork gives less.

In like manner, one also varies the wheelbase. The shortest fork gives a wheelbase of about 50 inches, and the longest fork stretches it out to about 51.5 inches. Remember that, other factors being equal, shorter wheelbase will result in quicker handling and more marked reaction to transfer of body weight.

So it is no surprise that the road racer was delivered to us with Yamaha forks, which, being the shortest, gave the most forward weight bias and slightly shorter wheelbase desirable characteristics for this sport. While the road racer's weight is not quite far enough forward, use of a fairing on this lightweight would just about bring the loading exactly into optimum position.

The road racer we tested had the Yamaha lOOcc twin engine, stock except for expansion chambers, and was geared a bit high for our heavyish staff. So the bike ran nearly as fast in third as it did in fourth (just under 70 mph}. As Rivôrside Raceway is rather vast at that speed, the throttle was held wide open through all except the three upper turns of the course. This was enough to show us that the road racer kit is quite stable, tracks well, and has the secure feel of a much larger machine, as well as fitting the lankiest of our riding staff. As is, it's a marvelous trainer, and some speed tuning will make it a first-rate weapon. Its only shortcoming was the weakish front brake, which is hardly Van Tech's fault and can easily be changed.

(Continued on following page)

The motocross model, in terms of weight bias, is at the other extreme — rearward — and the rake, naturally, is farther out. We tested a Hodaka-engined model with modified Hodaka telescopic forks, offering nearly five-inch travel. While the average buyer might not be likely to install the Girling shocks that were on our test bike, it must be restated for the umpteenth time that these are a superior product and hard to duplicate. (Van Tech is working on a shock absorber that he hopes will equal or better the performance of the Girling; a pair of his prototypes, calibrated and adjustable for rate, were mounted on the road racer and seemed to do the job quite well, at least at the slow speeds we were running).

Consensus on the motocross model after tests in Big Bear country was that it was better than any production dirt machine in its class save for one or two limitedquantity racers. There was no flailing about, front or rear, and the ride was soft and comfortable. The long wheelbase plays an important role in counteracting excessive front wheel rise which might result from the extreme rearward placement of weight.

A Honda S-90 powers the test TT version, which, like its predecessors, is a great slider, and may be rushed into a turn and flopped practically onto its cases with a reasonable expectation that the rider will leave the turn the way he came into it — on two wheels. This delightful characteristic is achieved with the S-90 forks, which are shorter and thus produce less rake and wheelbase on the Van Tech frame. Result: quicker front end response, and the ability to hold a tighter line and apply the power sooner on flat-track and graded scrambles circuits.

Why are these machines good? What is Van Tech's secret and where did he get it? If there is a "secret," it must be that Bill Van Tech is the USA's most methodical eclectic. His frames are not mere copies of any one frame, for he derived their dimensions and angles from an assemblage of "averages." To wit, given a certain group of machines that do well consistently in one or more phases of motorcycle sport, one discovers that they have certain proportions and angles in common.

The proportions of the first V«n Techs were all derived as an "average" of other good designs. Bill used to measure profile pictures out of CYCLE WORLD, when getting at the machine itself proved too expensive.

Later, as more of his frames went into use, Van Tech used feedback from his buyers to incorporate improvements into subsequent models, which changed quite frequently. The frame thus became more "his," with each bit of feedback. In the first few years of Van Tech, rarely were there more than five frames built alike. The largest identical batch was 25.

Of course, affiliation with Grant Industries to produce the frame in larger quantities will result in less frequent changes, but the experimentation still goes on.

The designer is interested, if there is a demand, in producing frames for bigger engines. One effort in that direction — a 250cc Yamaha-powered prototype scaled up from the small frame — was so devastating that it was ruled off the tracks in three short weeks. Most assuredly, we'll be hearing more from Bill Van Tech.