BONNEVILLE

BOB EBELING

WHEN DINOSAURS roamed the land, a deep, warm ocean flooded half a continent where mountains were yet to rise. Over millions of years the waters receded. Mountains were erected by pressures deen within the earth.

First the Goshute Indians, then questing pioneers came through the passes of the young mountains to cross the glaring white salt deposits, the remnants of the prehistoric sea.

Hard-fisted Irishers and quiet Chinese coolies laid the first level railroad bed across these seemingly endless expanses of crusty salinity.

Later, one Ferg Johnson, so legend has it, took a passenger. Bill Rishel, out upon the salt to discover what Johnson's Packard could do. A heavy foot caused the Packard to deliver a fantastic 50 mph — fantastic for it was but 1909.

Ever since, other heavy feet have pushed throttles to propel a variety of vehicles

over the salt in the quest for ultimate velocity.

This year, 1967, brought the 19th Annual Speed Trials at Bonneville Salt Flats, Utah, under sponsorship of the Southern California Timing Association.

Bonneville is the name of a man who claimed the vast expanse as his property and demanded his name be used in recognition of its use without financial reward. Today this is generally forgotten, and the name Bonneville only makes the blood pressure rise, and pulse quicken with an automatic association of the term "speed."

This year, for the second year in a row, salt conditions were perfect, humidity was low, temperature was at 110. Joys were unbounded and tears were unchecked.

All the old timers were there: Earl Flanders, AMA official; Rich Richards, his assistant; Burt Munro, 73-year-old New Zealand speedster. Richards almost enjoyed his speed week from the barred win-

dows of a local Wendover calaboose, when four deputies, the entire Wendover police department, were called to investigate a prowler behind the State Line Hotel. Heavily armed, the police surrounded the prowler and took him into custody, complete with the stolen property, a stick of wood that Rich wanted for a tent pole. Needless to say, charges weren't pressed, because he was a friend of the owner.

More than 50 entries were filed before the week had passed. These included men expected to reach the ultimate for two wheels — Bob Leppan with his Gyronaught X-l, Murray and Cook with their twinengined Triumph, and Rich and Gary Richards with a single-engine Triumph streamliner. Various occurrences kept these men from expected achievements. The fastest streamliner record was set by Burt Munro's Indian-powered machine, with a two-way average of 183.586 mph. Munro's fastest one-way speed was 190.07. Fastest honors for an unstreamlined machine were awarded to Warner Riley of Skokie, 111. Warner brought three things to Bonneville that helped make the record: one was a 1250-cc Harley Sportster; the second was Leo Payne, drag racer supreme and mechanical adviser; and the third, sponsorship by Sta-Lube Oil Co. Warner set a two-way average speed of 153.452 in the PS-A class and 149.782 for a C-A record. The 1250cc displacement bumped him just over the 1200cc class limit and placed him with %the 3^000 or 183-cu.-in. runners.

The achievement becomes even more fabulous when one realizes that both Warner and Burt were burning only gasoline, though fuel would not have changed their classes. A stranger to speed will look at the record book, see the engines classed as A, and say, "Oh, well, that's not fast for burning fuel." It's a shame there aren't designations AG for gas and AF for fuel.

Four-stroke advocates will have to swallow their pride and admit that Don Blessing's 250cc Suzuki is an oil injected wonder. Don set a two-way record of 128.182 mph! That was faster than any machine under 55 cu. in. for 1967!

Don McEvoy and Jimmy Enz may not have raced side by side, but to them it was the longest drag race ever run. On opening day, the machines were off loaded and gasoline was poured into their tanks. Enz' twin-engined Enfield turned a run of 164.53 mph. McEvoy's rider, Buddy Martinez, bolted through the traps at 160.42 on a twin-engined Triumph. All through Wednesday, each tried to outdo the other and tune to perfection in the same movement.

Thursday their speeds were scant hundredths apart, and, for the ultimate, each tipped the nitromethane cans and raced for qualifying spots faster than the record of 191.302, set last year by the Murray-Cook twin-engined Triumph. First off, Enz turned 178.21 mph and McEvoy clocked 179.64. Friday, time was running out and the nitro percentage climbed. Enz turned 184.80, McEvoy 184.04. With a little greater percentage of nitro, McEvoy tallied 190.89. Enz then turned 190.27, but broke a chain and shredded the rubber from his rear tire. Jimmy loaded into the trailer and mumbled, "That's all for this year, but next time, next year, I'll have new rubber and . . ."

McEvoy came right back out and pointed down the graded salt highway, his tires searching for the black line that led through the traps. His rider Martinez found it, and clocked a run of 194.80 mph. That put McEvoy and Martinez in the lineup for a last chance for record runs Saturday morning.

Boris Murray and Jim Cook were out on the Salt with a new streamlined fairing that placed them in the APS-A class. Their twin-engined Triumph was devouring pistons like a starved man with a bag of hamburgers. The hungry beast was not satisfied with just pistons, but ate two cylinder heads as well. Thursday, it appeared as though it was all over, but Nira Johnson, who established a record of 125.022 in the A-C class on his 650-cc Triumph, loaned Murray and Cook two cylinder heads. McEvoy provided some pistons, and the team was back in action.

Friday, they had a chance to satisfy their sponsor, Torco, and qualified for a record at 191.48 mph.

Bob Leppan and his able crew took to the salt on Thursday, but were only able to crank out a run of 241.44 mph from the Gyronaught streamliner. Friday, they knew time was short and added a percentage of nitro. The Gyro was towed to a start by a 40-ft. length of manila rope extended from the rear of a truck. When the engine had fired, the pit crew jumped from the truck and started the bulletshaped missile on its way with all of the speed they could muster afoot. Either they didn't run fast enough, or the gyro couldn't digest the nitro mix, for Leppan's best speed over a 4-mile run was 220.85 mph. All was over for last year's champion, and this year's slightly disappointed world's fastest motorcycle.

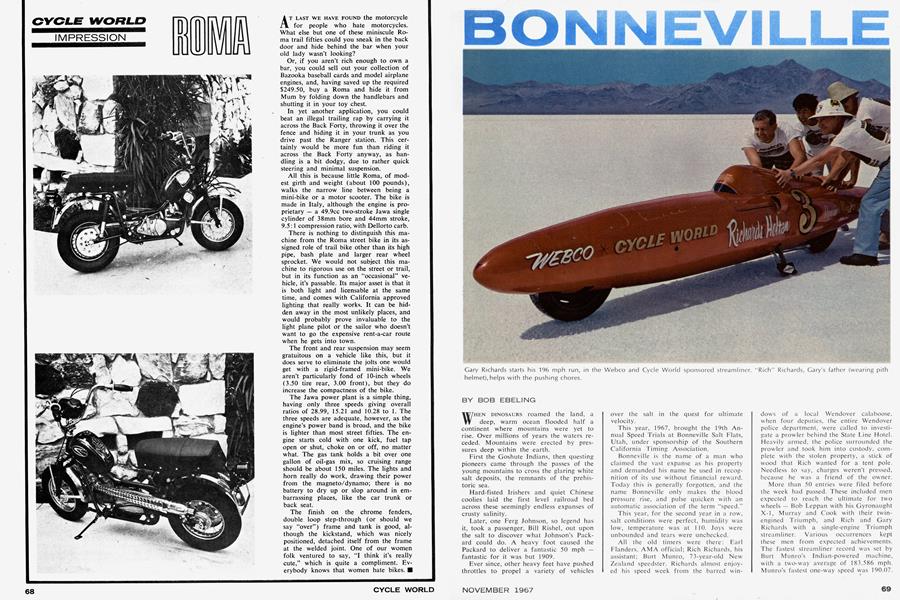

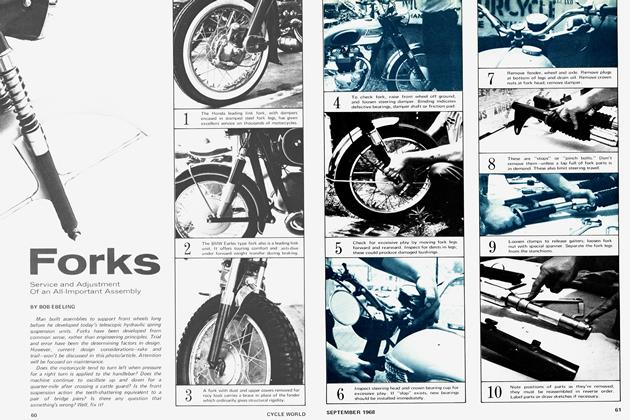

Pitted directly across from Leppan was the Richards-Webco-CycLE WORLD streamliner. All week long, jests and rude gestures were hurled back and forth, but the smiles left the faces of Gyronaught crewmen when Gary Richards made an easy first pass at 196.71 mph with the singleengined Triumph streamliner.

Old evil demon Bad Luck perched with one leg in the Leppan Camp and one in Richards', for neither managed to make the record run lineup. The skids on Richards' machine were knife-edged, rather than blunt, and were set too high. On one run, the machine rocked to the left, then right, and finally the left skid found a soft spot and dug 4 in. into the salt. The streamliner pivoted and dropped on its side, to what was an embarrassing repeat of a 1966 fish on dry land performance. Later, the skids were extended to eliminate rocking, and the clocks were stopped with a recorded run of 196.71 at five miles. This was Friday and time was up for additional attempts. Rich Richards said, "Always, in years past, I've left the streamliner in Gary's hands. This was my first time on the crew and I've learned a lot. Next year we will do it . . . next year."

Eighteen records were set during this year's speed trials. Bob Vaughan, running under a Salt Lake City dealer's banner, and carrying the colors of Sta-Lube and Kawasaki, was a greedy man. He set not one, but five records on a 175-cc machine. His best two-way average was 93.567. A real battle developed between two leading brands, Suzuki and Kawasaki, but 118.998 was the closest Kawasaki could come to the Suzuki 128 mph.

Honda was on the salt, but surely could have used some pepper as that marque's records were not astounding. Bob Green turned only 101.940 on a 450 for the A-C 500 record, and Dennis Manning set a record of 83.821 on a supercharged 450 Honda. One man that really tried hard was Harry Wolfley. Harry brought his 50-cc Honda to the flats to run on gasoline, but other contenders in the same class were fuel burners. In an effort to stay in contention he tipped the can. and without previous fuel experience, he stayed in front to take the record at 63.809 mph.

No one would believe the Don Vesco 100-cc Moto-Beta or the 500-cc Velocettes of Jim Eversole and Mark Lloyd Dees would stand a chance at setting records, but the brands came through. Vesco clock-

ed an 82.315 for an A-A record. The fastest Velo was ridden through the traps at 1 11.325 by Dees.

Of those aiming for records in partially or fully streamlined vehicles, Alex Tremulus was most likely to be found in the pit camp or at the judges' stand where times were distributed. His most avid desire is to produce additional proof that aerodynamics is the future for motorcycle design. Boris Murray's fairing wasn't mounted true, and its offset gave the impression that the machine always leaned to the side. At 190 mph plus, that false insecurity could lead to disaster. Alex moved in and taped the fairing deck and windshield with black electrical tape which provided a false horizon to create a secure sense of balance. He guided, watched and helped everyone who was reaching for speed. When Murray was preparing for a Saturday record run, Tremulus provided a good luck medallion for Boris to carry.

Saturday morning, all eyes were on McEvoy's twin-engined Triumph and Murray's partially streamlined speedster.

McEvoy's qualifying run appeared the one to better the existing record, but when Martinez cast off from the tow car and dropped the clutch, a chain parted and terminated his record run then and there.

Murray had only to better 156.586 for a record. As they towed and released, the engines responded with burps from an overrich mixture and still hadn't cleared their cylinders when the traps were reached. Yet the clocks read 160.714 mph! It was good enough. Leaning down should put the return run way up in mph.

As the oil was being changed, Murray found the rear wheel could barely turn. A frozen bearing! Jim Cook was dispatched to the starting area to borrow a wheel from McEvoy. The return run had to be made in one hour. Time was almost gone. Oil changed, fuel in, wheels on and chain adjusted, Murray told the official he was ready for the run and was towed on toward the traps. The engines sounded much better. But he used too much throttle and the rear wheel broke loose. Suddenly the bike lurched to the right and went off course. Speed must have been 170 or more. The spokes must have torn out, or perhaps a tire was coming off the rim, the rider thought.

Murray never made it through the corridor between the electric eyes. Instead, he passed off to one side. The machine was brought to a safe halt. What happened? Murray looked down and saw the axle nuts were not tightened, and the wheel had cocked in the frame. Rubber was stripped from the tire down to the cord. Why didn't it blow?

During each week, the machines that compete at Bonneville are disassembled and reassembled by owners to repair or improve chances at the records. Each machine is inspected only once — when it is signed in. The AMA would be well advised to have a safety inspector present at all times, and to check out before every run all machines that are expected to exceed 150 mph.

The AMA rule book should state that axle nuts must be secured with safety wire or cotter keys. As speeds increase, so do the chances for serious mishap.

The only rewards for record setting at Bonneville are a certificate and self-satisfaction, accompanied by the congratulations of a sponsor.

This year, two trophies were donated by Weber Tool Co., one for the fastest streamliner record and the other for the fastest open bike.

Only the slightest cost and effort could provide trophies by manufacturers, dealers and distributors for every class run at famed Bonneville. The AMA doubtless will find the time and make the effort for Bonneville 1968. ■