THE HISTORY OF JAPANESE MOTORCYCLES

W. B. SWIM

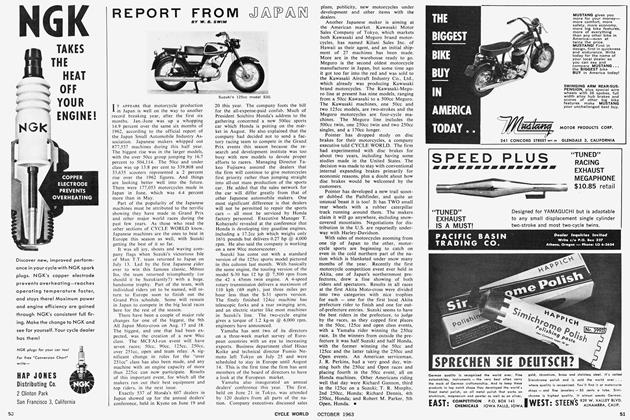

To the regular reader of CYCLE WORLD the name W. B. Swim is as familiar as that of the publisher. "Dub" has kept us all ap prised each month of the machinations and products of Japan's motorcycle indus try, "scooping" at times even the Japanese home press to provide us with details of some new model or other, long before the U. S. distributors had any certain in formation. Dub's intimacy, as a journalist, with the Japanese manufacturers is to be envied, and he comes by his position of respected reporter honestly, having been involved in the early growth of sport and industry in postwar Japan, when he chose to stay in that beautiful and sensitive coun try after his tour of duty with the Ameri can occupation forces had come to an end.

In those salad days, Dub, along with several other American servicemen, added a new dimension to Japan's sporting scene by injecting a touch of Yankee 45-inch "slidey" style into local dirt track events. The Japanese loved it, and Dub trotted off with some gold. In the years that followed, Dub developed a strong, working knowl edge of Japan's sport and industry, and he personally developed as a fine journalist. There is little doubt that there is anyone as qualified to tell this story as W. B. Swim. - Ed.

oDAY JAPAN is generally acknowledged as the world's foremost motorcycling nation, in terms of production, worldwide sales, Grand Prix racing victories, and even research and development of new mechanical features.

Japanese manufacturers are expected to run some 3,000,000 motorcycles off of their modern automated assembly lines during 1967, and export more than One million of them. Honda, the largest mak er in history, is turning out nearly 150,000 machines every month. Japanese factory teams also appear set to win dozens of OP races this year, quite possibly winding up with all five solo class World Cham pionships in the process. In fact, it's an upset when anyone beats the Japanese in road racing.

This unchallenged leadership, however, is strictly a postwar phenomenon. Before World War II, very few people outside Japan even knew motorcycles were built in the land of the rising sun, and fewer still had ever seen, much less owned, one.

Japan's first appearance at the Isle of Man TT races was in 1959, when Honda fielded three 125cc racers, finishing sixth, seventh and eighth. The next year Honda entered six races to gain experience for riders and performance figures for designers and engineers. Then, in 1961, Honda won 10 of the 11 250cc GP and TT races and 8 of the 11 125cc events, to cop World Championships in both classes, setting 11 new race speed records along the way.

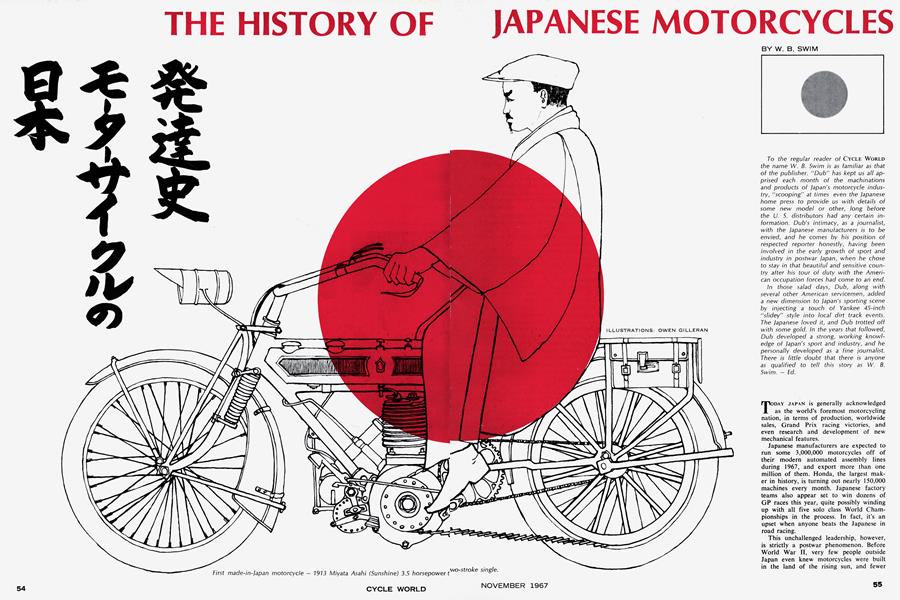

This modern glory dates back to before the turn of the century, when the first motorcycle was imported into Japan, and to 1913, when the first made-in-Japan motorcycle was built.

The first machine which might be classified as a motorcycle was imported in 1899. It was a steam engine-powered contraption with two large wheels mounting solid rubber tires and two tiny auxiliary wheels. If this vehicle can be considered a motorcycle, it was the first ever seen in Japan, although, unfortunately, the name of the maker and even the country of origin have been lost in the fogs of antiquity. It is recorded that the machine was imported by the Iizuka Trading Company of Tokyo.

Two or three other motorcycles were brought to Japan by foreigners during the early 1900s, but no record exists of exactly how many were brought in, the models or the foreign owners. They did, however, create much excitement from an amazed Japanese population wherever their foreign riders ventured.

In 1907, the Ishikawa Trading Company of Tokyo imported Triumph motorcycles from England, but no one remembers the number and size of the machines. That same year saw the first motorcycle race in Japan. Motorcycle racing in Japan got started on the coat-tails of bicycle racing.

In November, 1907, a bicycle race was held at Ueno in Tokyo. Motorcycle riders, using their standard road machines, of course, managed to steal the spotlight by staging an informal race over the bridle path that circled Ueno's Shinobazu Pond. Unfortunately, it is not known how many motorcycles participated, what makes were used, or who the daring riders were — or who won.

In 1908, Mr. Narazo Shimazu designed and built the first motorcycle engine ever made in Japan. He fitted it into a foreign frame, probably from one of the imported Triumphs. No size or performance figures have been preserved. That same year the Takagi Kyoseikan firm imported an engine and built a motorcycle frame around it. Also in 1908, the Miyata Works, makers of bicycles, began experimenting with making a motorcycle.

Formal permission was obtained from the government by different firms in 1909 and several motorcycles were imported into Japan on a commercial basis. These were mostly British makes, including Triumph and LMC (Lloyd), plus NSU and Progress bikes from Germany, and Indian motorcycles from the U. S.

During the same year companies in both Tokyo and Kyoto imported engines and began making motorcycles in Japan by manufacturing the cycle parts. These were

the first motorcycles built for sale — the first time motorcycle assembling became a commercial business in Japan.

Still riding in bicycle racing's slipstream, Japan's second motorcycle race took place in conjunction with a bicycle race at the Chikko Grounds near the harbor in Osaka in 1911. The next year another motorcycle race was held in Osaka, this time at the Hanshin Horse Race Course in Naruo, again as part of the bicycle program.

A year later, in 1913, the motorcyclists finally became independent of the cyclists and held the first motorcycle races not combined with bicycle events, at the Hanshin Horse Race Course in Osaka.

After experimenting off and on since 1908, Miyata began manufacturing a motorcycle powered by a 3.5 horsepower twostroke engine in 1913. Sold under the brand name "Asahi," and sometimes with it translated into English as "Sunrise," this machine was modeled rather closely after the British Triumph.

The size of the engine is not known now, but the Miyata firm manufactured both the engine and frame — a complete made-in-Japan motorcycle. Thus, this firm deserves credit for manufacturing the first Japanese motorcycle on a commercial basis, as well as being the first firm to make motorcycle engines, although some individuals had turned out "one-off" engines previously.

Most Japanese motorcycle riders, however, were not interested in Miyata's efforts and continued to demand foreign makes. These young men, interested in the latest things from the Western world, were termed rather derogatorily "mobo" from "modern boy." They had their count rparts on the pillions, the "moga," or "modern girl." The group was composed mostly of playboy sons of the wealthy, and enterprising young men such as photographers, watch dealers and tailors of Western-styled men's clothing.

A motorcycle imported during this period is the oldest machine still running in Japan. A 500cc 1914 Triumph single-cylinder side valve recently took second place at a vintage race held on Fuji Speedway. Probably the second oldest motorcycle still mobile in Japan is an American-made 119cc Evans two-stroke, which dates from the 1921 to '23 period.

Because the demand for their Japanmade motorcycle was so slight, Miyata was forced to suspend production in 1916. During those four years they had made between 30 and 40 motorcycles.

Motorcycle racing moved back to Tokyo in 1915, when a race was held at the Meguro Horse Race Course.

Around 1916, large 750cc and l,000cc Harley-Davidson and Indian motorcycles were imported from the United States and immediately made a hit with Japanese riders. They soon became the most popular brands in Japan, and the large machines rode the wave of popularity for more than five years.

In 1922, however, medium-sized motorcycles were imported in large numbers from England and Europe, and machines such as Triumph, Sunbeam and Norton once again climbed to the top of the popularity chart in Japan. During this period the only motorcycles in Japan were imported machines, as no Japanese manufac-

turer was making motorcycles at this time.

In 1923, however, some automobile manufacturers and parts makers decided to produce motorcycles which would be competitive with the imported machines. The Meguro Gear Manufacturing Company and the Omori factory of the Japan Automobile Company began test manufacturing and experimental sales of motorcycles.

The first motorcycle with a sidecar made in Japan was constructed by Kuwashi Katsu in 1924. He was helped in building the machine, which was modeled on a HarleyDavidson, by M. Murata, who later became the president of the Meguro motorcycle manufacturing company.

Japan was swept off its feet around 1926 by thrilling motorcycle racing. It became one of the country's favorite spectator sports. Machinery used was almost exclusively British and American, as the few made-in-Japan models were just not competitive. Events were dirt track and dirt road races.

It was not uncommon for a motorcycle race to attract 30,000 paying spectators, a tremendous crowd for any event in the Japan of those days. The racers were mostly motorcycle dealers, with a sprinkling of a few enthusiasts, who had organized clubs. The nation's largest newspapers sponsored many of the races, but wealthy sportsmen, cities and even villages also put on races throughout Japan.

Motorcycle clubs were organized in cities up and down the country, one after another. Some of the more famous were the Tokyo M. C. Kyokai, Osaka M. C. Doshikai, Nagoya M. C. Club, Kyoto Motor Kyokai Kobe M. C. and Hiroshima M. C. This was the real heyday of the motorcycling sport in Japan.

In 1933, Miyata Works resumed the manufacturing of motorcycles, and, in April, 1935, the firm commenced massproduction. They turned out a two-stroke 175cc single. It was still marketed under the "Asahi" name, and, with good performance, gained popularity and a good reputation. Miyata produced about 3,000 motorcycles before the beginning of World War II, when they were again forced to stop production.

During the same year Miyata began mass-production, 1935, the newly formed Rikuo Internal Combustion Company started making 1934 model Harley-Davidson 750cc motorcycles under license. These were sold in Japan under the "Rikuo" (Road King) brand name. The company had spent three years working out the agreement with the American manufacturer and gearing for production. The firm continued making these 1934 models until it went out of business in 1960.

Foreign motorcycle racers visited Japan for the first time in 1934, with the initial dirt track race being held at Inogashira in Tokyo. The five-man American team, headed by famed Pitt Mossman, had been invited to Japan by the Yokohama Port Festival Exhibition and raced before capacity crowds at several locations in the country during their stay.

They put on demonstrations of the first short track racing ever seen in Japan, and the team members became idols, mobbed by fans wherever they went, much like the Beatles of today.

The Americans rode Martin racing motorcycles powered by 500cc JAP engines. This was the first time Japanese riders had seen real racing machines, and they soon began experimenting with building racers of their own. Prior to this time, motorcycles used for races in Japan were merely standard street machines which had been modified to the extent of pulling off the lamps, etc., by the riders and their mechanics.

Soon American riders introduced board track racing to Japan, with only four machines competing in each race, and board tracks were built at several locations.

During the 1919 to 1935 period, many Japanese riders gained a high reputation for their skill and daring on the race course. Perhaps the outstanding rivalry among the riders of large displacement machines was between Yoshisaburo Matsumoto and Seijiro Osada. Matsumoto, from the Kanto (Tokyo-Yokohama) area, rode an Indian, and Osada, from Kansai, raced a Harley-Davidson.

Between 1927 and 1930, one of the most exciting competitions in the smaller class was the duel between Kazuo Takashima, who began racing Harley-Davidsons when he was 16 years old, and Isshin Shimamura, who rode Belgian and English racing motorcycles. Another noted racer of this period was Kenzo Tada, who was at his peak in 1927, when he was the first Japanese rider ever to compete in the Isle of Man TT. He piloted a 350cc Velocette on the Island after making his name in long distance cross-country races in Japan, first on bicycles and later switching to motorcycles.

A final name which must be included in the list of prewar Japanese motorcycle racers is that of Miss Ayako Nishino. She was the only woman racer before the war, competing successfully from 1930 to 1932 on Francis Barnett and Evans motorcycles. She rode against the men in every type of event, beating most of them.

The last race held in the Tokyo area (before World War II put a halt to racing for the duration) was staged at the 3/4mile paved Tamagawa Olympia Speedway in 1939. Further away from the restrictions surrounding the headquarters of the Japanese military in Tokyo, enthusiasts in Hiroshima managed to hold the final prewar race in 1940.

During the war, the Japanese army ordered motorcycle makers to standardize and produce only 350cc models. Miyata was also ordered to produce a 350cc for the army, and, after two years of blueprinting and experimenting, the firm turned out a few machines before the end of the war.

Motorcycle production figures before 1930 are not available, but in that year a total of 1,350 were made in Japan. The 2,000 mark was first topped in 1937, and the 3,000 mark in 1940. This was the peak prewar year, with 3,037 motorcycles being produced. As the war advanced, production fell rapidly back to 1,029 in 1944.

At the end of the war, Japan was a bombed ruin with a total lack of almost everything, including everything needed to manufacture motorcycles. Only 127 were made in 1945, and the total the next year was a mere 211, climbing to 387 in 1947.

Led by the motor scooters, of which 1,623 were turned out in 1947, Japan's

motorcycle makers began to get back on their feet in 1948 when they produced some 1,000 machines. The next year 1,766 motorcycles were manufactured, and this went up to 2,633 in 1950.

The year 1951 was Japan's blast-off year in motorcycle production, marking the start of this Far Eastern nation's climb to world leadership. Makers nearly quadrupled production over the previous year when they turned out 11,510 machines.

This was only the start to the most phenomenal increase of production in the world's history. The next year saw 48,800 new registrations, and the tremendous figure of 1,000,000 machines was topped only eight years later, in 1960, when Japan made 1,349,090 motorcycles.

The rise was steady and spectacular during these tremendous eight years, jumping to 111,716 in 1953, 119,632 in 1954, 204,304 in 1955, 258,298 in 1956, 308,926 in

1957, and 389,869 in 1958.

Then came Honda's "nifty fifty" for the nicest people, announced in October of

1958. It caught on immediately, and production in 1959 soared to 755,589. Other Japanese makers quickly brought out imi-

tations of this Honda 50cc step-through, although Honda kept 75 percent of the market, so that production figures topped the 1,000,000 mark the next year.

Business continued to be favorable in 1961, and production amounted to 1,713,288. The next year threw a scare into the industry, however, and, incidentally, caused the failure of several of the smaller manufacturers. Although exports nearly tripled, the 50cc boom came to an end, and production fell back to 1,607,272.

The remaining makers quickly created the new 90cc class and turned their production and sales efforts into persuading ex-50cc riders to "step up" to a 90cc bike. Success crowned their efforts, and in 1963 they more than regained what they had lost the year before, with production figures totaling 1,863,989.

The two million mark was bested in 1964, when 2,056,236 motorcycles were made in Japan. This was followed the next year with 2,177,215 and then 2,413,388 in 1966. Expectations are that the two and a half million mark will be well passed this year.

Japanese motorcycles got their start in the export market way back in 1947, when a grand total of ten were shipped overseas to Okinawa, a former part of Japan. No exports worthy of the name were made until more than ten years later, however, with the figures for 1956 being only 207. This was increased to 430 the next year.

Japan's big makers were already determined to develop an export market by this time, nevertheless. Honda's president announced in 1954 that Honda would compete in the Isle of Man TT races sometime in the future. That year he went to watch the races, and was surprised! He found the racers there putting out three times as much horsepower as he was getting from his products with the same engine capacity.

Honda's first racer sent overseas was a 90cc bored out to 125cc, and it had only a two-speed transmission. It had a dirt track type pipe frame and top speed was below 70 mph. Mikio Omura was sent to Brazil to participate in the road race held on the occasion of the city of Sao Paulo's 400th anniversary. He didn't manage to come anywhere near winning an award.

Yamaha set their sights on the American market. To get the brand name known, they sent Fumio Ito to the race on Catalina Island in 1958. He rode a racer with a tuned-up YD-1 250cc engine mounted in the frame of the new YDS-1, which hadn't been put on sale at that time. He finished sixth overall, which was considered a very creditable showing. The purpose of both factories, of course, was to get their name known so they could increase exports.

Honda did the job very well in 1959, when their three entries in the Isle of Man TT 125cc race finished sixth, seventh and eighth to take home the Manufacturer's Team Prize on the firm's first outing.

Exports did not begin in earnest, despite these early efforts, until 1959, when the 13,142 machines sold overseas were more than ten times the 1,078 exported the year before.

Exports rose by leaps and bounds as the low price and good quality of the motorcycles and the unique utility of the 50cc step-through models became known in ever-widening markets. Exports totaled 52,391 in 1960, 76,234 in 1961, 199,266 in 1962 and 396,957 in 1963 and topped the half-million mark with 590,708 the next year.

The upward trend continued, with 865,885 motorcycles going overseas in 1965 and 974,569 last year. The makers expect to top the million mark easily this year.

First into production after the war were the wartime makers, of course, led by Meguro, Rikuo and Miyata. Before long, others saw the advantage of making motorcycles. Early in the game were Tohatsu, Pointer, Abe Star and Mishima. The first two grew to the point that both were ready to enter GP racing before going out of business — Pointer in 1963 and Tohatsu in 1964, after having built up a good start in exporting to the United States.

Although getting a later start, Yamaguchi also made considerable exports to the U. S. before going under in 1963. Several other makers worked up to the point of turning out fairly large numbers of machines and making a reasonable profit out of the business, before going broke. Included among these, any of which except

for the fortunes of the game might have managed to survive until today, are Mizuho, Sumida, IMC, Portly, Olympus, Gas Den, Hosk, Martin, Showa and Cruiser.

Many other makers were in production for a longer or shorter time after the war, but never really made a go of the business, such as Hope Star, Health, Pearl, Queen Bee, Happy, Pony, Center, Martin, Taiyo, Jet and others too numerous to mention. Several of them, never having a nationwide distribution network, depended instead on sales in their local areas.

Most manufacturers were centered in the central Japan city of Hamamatsu, which at one time had 44 motorcycle makers in production. This city is still the center of the industry, with factories of Honda, Suzuki, Yamaha and Lilac (Marusho) located there.

The number of manufacturers neared the peak of about 120 companies in 1952, with approximately 70 registered with the government, and remained on this high level until 1955, when there were 73 registered, before falling drastically year after year until only seven makers remain today.

The first motorcycle race held in Japan after the end of World War II was run over the badly potholed Tamagawa Speedway in 1949. Some 100 entries on all sorts of wired-together prewar equipment participated on the 3/4-mile paved oval. Several American servicemen had ridden their postwar Harley-Davidsons, Indians, Ariel square fours, and BSAs to the course, intending to watch the races. They were persuaded to pull off the headlamps and stage an "exhibition" race, so the Japanese riders and the spectators could get a good look at the new motorcycles. The Americans didn't know the meaning of the word "exhibition," however, and your correspondent was privileged to collect his first trophy with a 1948 H-D 750cc.

Following in the footsteps of bicycle racing — regulated by the government and featuring pari-mutuel betting, like horse racing — professional dirt track motorcycle racing was the next in the order of business after the war, other than a few club-sponsored events drawing only ten or twenty entries here and there. The pros started on 1/2-mile dirt or cinder tracks in October, 1950, and seven classes according to engine displacement were set up. The purpose, officially, was to earn money from the bettors for the hard-pressed local governments sponsoring the races and to promote the development of Japan's motorcycle manufacturing industry. Although most of the ride-for-cash boys were sons of motorcycle shop owners or their mechanics — riders who would have been satisfied with racing for the sport of it if any amateur racing had been going on — the racing succeeded in attracting only gamblers, not motorcycle enthusiasts.

The same year, the most active club of American servicemen, the AMA-affiliated All-Japan Motorcycle Club, sponsored the first of its series of charity races, with all profits from ticket sales going to the Red Cross, Japanese Olympic Committee, and similar organizations. The first event was held on the Tamagawa Speedway, but, after professional racing had gotten the tracks built, the venue was switched to the 1/2-mile dirt tracks. These were relatively small events, although drawing as many as

20,000 paying spectators in amusementshort postwar Japan, with less than 100 entries for each annual race.

Racing which drew nationwide interest began in 1953, when the newly-formed Tokyo Motorcycle Race Association sponsored the first Mt. Fuji Motorcycle Climbing Race. This group of Tokyo retail motorcycle dealers put on the race annually for three years. It was a timed hillclimb rather than a race, with the winner decided by comparing times each rider took to blast about five miles up the lower slopes of Mt. Fuji along a twisting volcanic ash road. Entries numbered from 40 to 50 tuned production model machines, and the 250cc and 125cc classes were catered to. Monarch won the 250cc event the first two years, with Honda taking the 125cc class. In the last year it was held, 1955, Yamaha's new A-l copy of the DKW beat out Honda in the smaller class, while a Honda took home the 250cc trophy.

The next big series of competition events started in 1955, when the large manufacturers got together in the new Nihon Motorcycle Race Association and put on the Asama Volcano road races every other year. These were held over volcanic ash roads at the foot of Mt. Asama. The roads were normally used as a government test course. Japan's major makers, including Honda, Yamaha and Suzuki, entered factory teams. Yamaha swept away the opposition with its new 125cc YA-1, taking first, second and third places. Effective publicity of this race win earned the YA-1 a good reputation, sales zoomed, and the new maker was on its feet and off running. The Asama races were held in 1955, 1957 and 1959 with from 50 to 70 entries each time.

The big series of races, which has continued to date, started in 1958. That year the publisher of a motorcycle magazine, dissatisfied to see competition under the control of the factories, organized several motorcycle clubs into the Motorcycle Club Federation of All Japan (MCFAJ). This new federation sponsored its first Clubmen's Road Race, borrowing the unimproved Asama test course. This event drew more than 120 entries, and equipment was limited to production machines with a minimum of tuning up. Honda, however, showed up with factory machines for its team riders. A heated difference of opinion arose, and they ended up riding in an exhibition race. Thus, the new MCFAJ made a powerful, and apparently eternal, enemy. The outfit is still boycotted by Honda to this day.

In 1959, the new MCFAJ agreed to combine their Clubmen's race with the Asama Volcano race, as there was no other course available, and the makers' association was rather insistent. Thus, factory teams were allowed, and Honda was victorious with a four-cylinder 250cc machine. From 1960, however, the MCFAJ either used U. S. military air bases and other courses, or skipped the race in years when no course was available.

In 1950, Kenzo Tada, Japan's only prewar rider at the Isle of Man TT had decided that Japan needed a motorcycle sports organization. After conferring with the Auto-Cycle Union of England by letter, he set up the Motorcycling Federation of Japan (MFJ), fashioned after the A-CU, and affiliated with the Federation International de Motorcycliste. The MFJ, however, was very inactive, never sponsoring any competition events nor even paying its FIM dues, although somehow the federation managed to build up a considerable debt.

Strapped for cash and in debt to the tune of some $1,500, Mr. Tada was happy to hand over control of the organization to a motorcycle magazine publisher who offered to pay off the debts in 1956. But, again, the MFJ did nothing while in the hands of the publisher, never sponsoring any competition events. Nevertheless, it was there, and was affiliated with the FIM.

Honda had some trouble getting international licenses for its riders going to the Isle of Man TT in 1959, and, after the difference of opinion with the fledgling MCFAJ which wouldn't let its factory machines run in 1958, decided it needed the MFJ, both for FIM licensing and to use to fight the MCFAJ. So practical Honda offered the magazinei publisher some $3,000 for the MFJ, and it was duly sold. Honda then quickly, persuaded the other major manufacturers to disband the Nihon Motorcycle Race Association and join them in the MFJ.

In later years, the MFJ has become more and more active in sponsoring not only road races, but also motocross, and a few flat tracks and rallies. Although basically an organization of individuals, in addition to the factories (which pay most of its expenses) in recent years the MFJ has instituted a "group" membership plan as well to fight the MCFAJ, which is composed entirely of clubs and has no individual members and, of course, receives no support from the makers.

In 1967, the two organizations sponsored or sanctioned around 300 motorcycle races of one type or another, more than half of them motocross and scrambles. It was estimated that during that year there were some 1,000 riders holding a competition license from one organization or the other, most with licenses from both. Factory teams were regular participants in MFJ events, but also entered the major MCFAJ races.

None of the prewar makers survived in the postwar competition, although all tried their hand. There was very little original design in Japanese motorcycles before World War II, with practically everything being copied from successful foreign motorcycles, either with a technical agreement with the foreign maker or without one. Postwar Japan was pretty well more of the same, with most of the dozens of postwar companies getting into business by copying some foreign or local motorcycle. Most of them continued only to copy or make only few modifications, and most of them went bankrupt. The only manufacturers to survive, with one exception, were the ones who soon discarded their copies of foreign motorcycles and struck out on their own to make something newer and better, or at least better suited to Japanese road conditions and the rider's taste.

Honda is the oldest of the seven surviving motorcycle manufacturers in Japan, having been established in September, 1948. President Soichiro Honda, self-educated son of a blacksmith with a wealth of varied experience including repairing

and racing automobiles, manufacturing piston rings, making salt out of sea water and trying to improve on weaving machines, purchased 500 tiny war-surplus two-stroke engines designed to power communications equipment. In transportation-short Japan, he fitted these engines to bicycles and found a hot seller on his hands. It was nearly too good, in fact, because he was soon out of engines. With no more available, this self-taught engineer, who now holds more than 100 patents, simply sat down and designed himself a 50cc two-stroke engine which would turn out 1/2 horsepower. He hung it in a bicycle frame and was soon back in business. This was dubbed the A-type, but also known as the "chimney" engine because of the odd, stuck-out-on-top shape of the cylinderhead. The A-type sold like crazy. There was such a demand, the ten workers in their 12 by 18-foot shack couldn't come anywhere close to making enough. So Mr. Honda incorporated the company, with a capital of $2,777, and hired more workers until he had 34 on the payroll.

There were eight other motorcycle makers in Japan when Honda started in 1948, but none of them manufactured a complete machine. They were engine makers or frame makers, but not both. Mr. Honda's dream was to make the whole works himself, and he succeeded in August, 1949, with the fourth engine off the drawing board, the 2.3 horsepower lOOcc twostroke single D-type. It was promptly named the "Dream," a name Honda continues to use today in Japan. The Dream had a two-speed gearbox, chain drive, and pressed steel channel frame.

This bike was a big seller, and in 1950, the Hamamatsu company opened its first office in Tokyo and managed to obtain a $5,500 loan from the government. With this cash he bought enough machinery to turn out 300 motorcycles per month, only to be accused immediately by his eight competitors of trying to get a larger ration of gasoline, which was a big blackmarket item. They said nobody could possibly sell 300 motorcycles in a month, which sounds reasonable, when you remember that all nine makers put together had only turned out 1,608 motorcycles during the past 12 months.

Honda simply designed a new motorcycle, the first postwar model to sell in the thousands of units. This was a 90cc four-stroke single with a channel frame. First models had a two-speed transmission, but the later 2-E and 3-E models had a three-speed gearbox. This first adventure in the four-stroke world — and more than 32,000 of these overhead valve models were sold in 1953 — blasted Honda way out in front of the competition in Japan and put the company on a firm footing. Capital was increased to $166,000, sixty times the amount the firm had started with five years before.

Now they were selling to motorcycle enthusiasts more than to people that needed inexpensive transportation, however, and that's not how the company started. So it was back to bicycles again, this time with a 1/2-horsepower 50cc two-stroke engine which was mounted on the rear axle, rather than hung in the center of the frame. This "Bike Cub" was soon darting in and out of alleys and byways throughout Ja-

pan, and soon had plenty of imitators. Honda was soon selling 6,500 every month and hanging on to 70 percent of the clipon market. Now Honda finally got around to copying somebody itself, and the next off the line was the 1953 Benly (which translates "convenient" or "handy"), looking suspiciously like the NSU Fox. It was a 90cc four-stroke turning out 3.8 hp with pressed steel backbone frame, telescopic fork, seesaw rear suspension and the engine sticking out in front with no support. Although production went up to 1,000 monthly, this J-type wasn't kept in the line long.

In late 1952, Honda, still capitalized at $166,000, purchased $1,111,000 worth of American, German and Swiss machine tools, because they found they had gone as far as local machine tools could take them. Also, motorcycle makers had increased in number to 55 and the competition was becoming more severe. When the new machines were delivered in 1954, Honda started making the 4-E model. This historic 5.5 horsepower 150cc single with a top speed of 50 mph sold so fast it paid for the new machinery within a few months, and Honda was the largest manufacturer of motorcycles in the world.

Still, Honda was just another motorcycle maker, perhaps a bit brighter than the next fellow, just a bit larger than anyone else, and perhaps with a bit bigger dream. Certainly, the young firm poured a lot of money into research, but apart from that and the tons of new machinery, it was not much different from anyone else in the game.

In 1958, however, all this was to change. The firm's super-salesman managing director, Mr. Takeo Fujisawa, had a new idea. He talked it over with the firm's super-inventor, the president. President Honda designed a new bike, and it started rolling off the production line on June 17. This was the ohv 50cc step-through "nifty fifty."

Until this time, all the world's motorcycle makers were trying their best to turn out a machine the limited number of motorcyclists would buy. In many places, such as the United States, the image of the motorcyclists was not good, to say the least. Mr. Fujisawa reasoned that Honda could become the world's largest maker of motorcycles, and still not amount to a hill of beans, in comparison with first-line major companies, such as automobile manufacturers, steel makers, etc. He decided the thing to do was to ignore the motorcyclists and build something he could sell to the "man in the street." The Supercub, as the step-through 50 was dubbed in Japan, was the result. Its design is the one which earned the president an award from the Emperor. A tremendous publicity and advertising budget was used to rewrite the "black leather jacket" motorcyclist image and to interest people in the Supercub who had never thought of two wheels as easy to ride, economical transportation. That success crowned these efforts is now old news, and Honda punched out more than 3,500,000 of these Supercubs with hardly a change, before switching to an overhead camshaft engine and larger lamps in 1967. After adding 65cc and 90cc engines to the step-through line, Honda ran the 5,000,000th Supercub off the line on April 10, 1967 — just eight years and nine months after the first one was produced. At the time, the firm's production was on the 1,500,000 per year mark, completely out of reach of the world's second largest maker, who at the time was turning out less than 500,000 annually.

Suzuki, the world's largest maker of two-stroke motorcycles and second in production figures after Honda, is the next oldest of Japan's surviving makers. The company was founded in 1909 as the Suzuki Loom Works, making weaving machines. They got most of their eggs into the export market and most of that in exports to Indonesia, which suddenly prohibited imports of weaving machinery, and there was Suzuki with a factory and payroll and no market for its products. As the motorcycle market in Japan was looking good about this time, Suzuki began making clip-on motors for bicycles in 1951. The Mini-free bicycle engine was a two-stroke 36cc unit.

Despite development, this proved to be underpowered, so, in 1953, the 60cc twostroke Diamond Free was put into production. With this model, Suzuki began fitting the engines to bicycle frames at the factory and selling complete machines. This one soon became popular, and before long, was a best seller, making a lot of money for the company and really putting it on its feet in the motorized twowheeler world. The Diamond Free gained its high reputation because it seldom needed the attention of a mechanic, and it had enough power to climb up Japan's multitude of hills. For 1955, a larger lOOcc two stroke engine was installed.

The year before, however, Suzuki produced a motorcycle powered by a 90cc four-stroke engine. This single-cylinder machine was named the "Colleda" (which translates, "This is it!"), a name still used by the company today. In 1955, a 125cc ohv four-stroke, the Colleda COX, joined the line and sold well. Later in the year, a two-stroke 125cc replaced it, and Suzuki has stuck to two-stroke engines ever since.

Suzuki's flirt with copying came in 1957 with a two-stroke 250cc twin equipped with a rotary shifting four speed transmission. It looked very like the Adler.

The first Japanese motorcycle with an electric starter was a Suzuki, as the firm fitted a starter to its 150cc two-stroke twin Colleda Seltwin SBS in 1959. It proved popular, and before too long, other makers began offering electric starters.

Other important milestones in the firm's history include its 50cc step-through, which actually beat the Honda Supercub to the market by a few days, but lost out in the sales war, and the K-10 and K-ll 80cc models which were developed from this 50cc engine. Suzuki's 80cc machines, introduced in 1962, kicked off the boom in the "step-up" 90cc class, as buyers were just beginning to tire of the 50cc machines. These dependable 80cc bikes have been a mainstay of the Suzuki line ever since.

The next year, Suzuki established a distributing company in the United States, increasing its capital for the fourth time since beginning to make motorcycles to $13,055,000 from the original $1,390.

Lilac got its start under the name of Marusho in 1952, when it began producing a copy of Honda's popular E-type. It

was fitted with a 150cc ohv single engine and a pressed channel frame, but differed from the Honda in that it featured shaft drive. A pipe frame was adopted later, and this version sold enough to put the firm on its financial feet. At the second Tokyo Motor Show in 1954 Lilac showed the Baby Lilac, a 90cc ohv single "shafty" with a big bore middle bone pipe frame. The firm is best known for its unique or "freak" motorcycles, turning out dozens of odd-ball machines one after another, but generally without finding enough buyers to pay for the tooling up.

Lilac's first copy of a foreign machine came with the 350cc side valve twin dubbed the Dragon. It was very much like a Zundapp.

A major racing success crowned the firm's efforts to be unique when a 250cc Lilac with a pipe frame and swinging arm rear suspension was ridden to victory by Fumio Ito in the 1955 Asama Volcano race. This race win was dimmed only slightly by the fact that most of the Honda factory entries retired, and for a time, the firm's motorcycles sold well.

The money was used to develop a 125cc two-stroke with a shaft drive, but this proved too unique and didn't sell. The company went back to four-strokes, coming up with a V-twin in late 1959. Several sizes from 125cc to 330cc were turned out one after another, but none caught on. Marusho finally found its debts too much shortly after setting up a distributor in California and declared bankruptcy. After a couple of years, however, a new company named Lilac, after its brand name on the machines through the years, was formed and production of a 500cc opposed twin much like the BMW was resumed. In recent months, however, production has never exceeded 100.

Bridgestone also got its start in 1952. The company is Japan's oldest and largest tire maker and also a major manufacturer of bicycles. Bridgestone's first bike was a clip-on engine for its bicycles, named the "BS Motor." This was made by the Prince automobile manufacturing company, which has close affiliations with Bridgestone, as was the first motorcycle, the 50cc forced aircooled Champion I. The BS Motor was unique in that it was fitted to the rear wheel of the bicycle "upside down" with the spark plug on the bottom. It was also quite unique in that the first few produced did not have any piston rings. This was soon remedied, however, when the problem of seizure from overheating every ten minutes proved just a bit too much.

The first motorbike which Bridgestone built itself was a two-speed 50cc twostroke with a cooling fan. It was mounted in a diecast frame. This Champion II was produced in April, 1960 and was followed by a model III with three speeds the following year.

Bridgestone finally had a good seller on its hands in 1964 with its 90cc Sports, which sold enough to let the company get on with developing bigger models, the 175cc dual rotary disc twin in 1965 and a 350cc in 1967.

Kawasaki got into the motorcycle business through the back door. Part of a giant prewar zaibatsu of industrial firms, Kawasaki Aircraft found itself with nothing to do after the war, when the victory pro-

hibited Japan from manufacturing airplanes. The company started making engines and transmission gears. One of its 250cc two-stroke twin engines was sold to a company which put it in a motorcycle frame in 1953. This was the Meihatsu, and it featured a transmission which could be shifted directly into neutral from any gear, like an automobile gearbox.

Kawasaki began making motorcycles itself in 1961, after Meihatsu went out of business. Its first model was the B-7, a 125cc two-stroke single. The styling was not good, however, and before long the company came out with the B-8, the same engine mounted in a pressed backbone frame. This one caught on, and the firm was in business.

Next major step was development of the B-1M, a 65cc with a rotary disc valve. It was soon followed by the 85cc J-l, and this was the biggest seller in the company's history, enabling development of the dual rotary disc valve 250cc A-l and 350cc A-7. When Meguro became bankrupt in 1963, Kawasaki bought out the company and developed a Meguro 500cc four-stroke ohv twin into the 650cc W-l.

Yamaha was the last of the major motorcycle makers in Japan to turn its efforts to two-wheelers. The parent firm, Nihon Gakki (Japan Musical Instruments), is Japan's largest maker of pianos and other musical instruments. In the early 1950s, the firm's president bought a DKW and found it so convenient in transportation-short postwar Japan that he ordered his factory to start making motorcycles, with the first production beginning in late

1954. Two engineers were sent to the DKW factory, and Yamaha's first machine was a two-stroke 125cc single which was pretty well a copy of the DKW. It was the historic YA-1, and proved a winner by taking Japan's major motorcycle races in

1955. The YA-1 was an instant success, and Yamaha was in business with its very first effort. In 1956, a 175cc version, the YC-1, came out, boasting 10.3 bhp and a top speed of 60 mph, but the frame proved weak. This brought on the YA-2 in 1957 mounted in a pressed steel frame and, later the same year, the YD-1 250cc two-stroke twin.

Yamaha was strong in racing from the very start, and its rapid growth in popularity and business was due, in part, to its racing successes. The best seller of the early models was the 250cc YD-2 put out in 1959 with an electric starter. The same year saw the sports version of the 250cc, the YDS-1.

Biggest of the modern bikes was the 75cc YG-1 introduced in 1963, while later models included a lOOcc twin and a 350cc.

The latest Japanese motorcycle is the Hodaka. The firm making it earlier made transmissions for the Yamaguchi. After Yamaguchi went out of business in 1963, the American importer, Pacific Basin Trading Co., hurried to Japan and persuaded the transmission company to make him a 90cc two-stroke single trail machine to their designs. It was an instant seller in the United States, and more than 10,000 have been sold to date with practically no change in design. The firm makes only the single model, for export to the U. S. only, and none are available in Japan or elsewhere. (Continued on page 88)

Japanese racing motorcycles today are acknowledged as the best in international road racing. In any Grand Prix, the machine to beat is invariably a made-in-Japan racer. This, however, is a rather recent development, and came about from the intensive and expensive efforts of the Japanese makers to use the World Championship classic events to get their name known around the world, and so promote exports.

Mr. Honda's brash 1954 announcement that he would send racers to compete in the famed Isle of Man Tourist Trophy races actually did not create much of a stir even in Japan and only a chuckle abroad. Likewise, Honda's abortive 125cc two-speed racer sent to Brazil in 1954 and Yamaha's sixth place at Catalina Island in 1958, did little to bring Japanese motorcycles to the attention of enthusiasts abroad.

Eyes popped and racing followers around the world were astounded in 1959, however, when Honda's three 125cc entries at the Isle of Man TT came in sixth, seventh and eighth with Japanese riders, to cop the manufacturer's prize. This was the first Japanese entry in the classic races, and it proved to be only a small hint of what was to come.

In 1960, both Honda and Suzuki sent factory teams to Europe for the GP races, but the year was spent in learning the circuits and sorting out the machinery. It was also found that foreign riders were needed.

The beginning of the deluge came in 1961. Honda, fielding a team of foreign and Japanese riders, won World Championships in both classes they contested, with Mike Hailwood in the 250cc and Tom Phillis in the 125cc class. Honda riders won ten of the eleven 250cc races and eight of the eleven 125cc events. The factory had a perfect 48 point score in both classes, as only the best six placings counted toward the championship. To indicate how sweeping was Honda's domination of these two classes, consider that Honda riders were ranked 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th, 10th, 13th, and 16th in the 250cc class and 1st, 3rd, 4th, 5th, 6th, 9th, 10th, and 15th in the 125cc individual rankings. Honda's Kunimitsu Takahashi was the first Japanese rider to win a GP race, taking the trophy at the West German GP in the 250cc class. Suzuki and Yamaha also sent over factory teams in both the 250cc and 125cc classes, Suzuki using both foreign and Japanese riders and Yamaha having mostly Japanese teammen sort out their racers' teething troubles.

Honda entered the 350cc class for the first time in 1962 and immediately took the title. Jim Redman made it a double for himself by winning the 250cc championship as well, and 125cc rider Luigi Taveri gave Honda its third crown of the year. The 50cc class was organized this year, and Suzuki's Ernst Degner brought this maker's championship home to Japan, although losing the rider's crown to Kreidler's Hans-Georg Anscheidt by a single point. Yamaha again participated, but had yet to win a championship.

By this time it was the Japanese you had to beat in any class they entered. In fact, in most classes they had progressed to the point that the only thing to be decided by the FIM series was which Japanese factory took the crown. The Japanese racers had developed to the point where they were their own greatest competition.

Honda put more than $5,000,000 on the line and built the six kilometer (3.7 mile) Suzuka Circuit, so they could show their stuff before the home audience. In November of 1962, this new circuit was the site of the first All-Japan Championship Road Race Meeting, and the factories had their star foreign riders on hand to do their stuff. Honda won all four races, but Suzuki gained second and third in the 50cc race and second in the 125cc, while Yamaha managed third place in the 250cc event.

It was more of the same in 1963 with the titles going to Honda's Jim Redman in the 350cc and 250cc and Suzuki's Hugh Anderson in the 125cc and 50cc classes. This year saw the inauguration of the Japan Grand Prix. The gruelling Isle of Man TT was won by a Japanese rider for the first time, the honors going to Suzuki's Mitsuo Ito in the 50cc race.

Yamaha's first world champion was Phil Read in the 250cc class in 1964. Honda's Jim Redman took the 350cc crown, and Luigi Taveri copped the 125cc crown for Honda, leaving the 50cc title for Suzuki's Hugh Anderson. The next year was more of the same, with Honda getting the 350cc with Jim Redman, Yamaha the 250cc with Phil Read, Suzuki the 125cc with Hugh Anderson, and Honda the 50cc with Ralph Bryans.

Honda won all five solo makers' championships in 1966, the first time any company had pulled off this trick, but lost the 50cc rider's crown to Suzuki's HansGeorg Anscheidt by boycotting the fourth Japan GP, which was held at the independent Fuji Speedway for the first time, rather than at Honda's Suzuka Circuit. The 500cc title went to MV's Giacomo Agostini, although Honda won the maker's crown in its first try at the big class. Riders' championships were won by Honda riders Mike Hailwood in the 350cc and 250cc and Luigi Taveri in the 125cc class.

Suzuki has sent a 250cc two-stroke single scrambler to compete in the international motocross series in Europe each year since 1965, but without any results to date. Yamaha has won consistently at the 250cc combined race at Daytona in the U. S., and now other Japanese factories are eyeing this largest U. S. road race. If the AMA limit is lowered to 350cc in 1968 as suggested, the Japanese factories should find themselves in a strong position for competing in the United States, as all makers other than Honda already had 350cc street machines on sale as of this writing.

Whether on the world's most famous race courses or in the market places around the globe, Japanese motorcycles are unchallenged leaders as this is being written in 1967. It's a truly amazing accomplishment, considering the short history of the industry in Japan. ■