THE SCENE

IVAN J. WAGAR

BEING able to return to the Isle of Man as a journalist was indeed a pleasure. And getting out of bed at four in the morning was completely voluntary, with no thoughts of climbing into cold, soggy leathers that hadn't dried for a week.

Also, there was the advantage of knowing most of what was happening. Because, as a rider, there is so much work to be done on the machine and so many practice periods, that precious littje time is left for anything else. The factory riders have things a little better, especially the ones on Japanese machines, with a horde of mechanics and a team manager to look after schedules and the like. On the other hand, the works riders invariably had to come up the hard way before getting a contract and the benefits that go with it.

But the life of the contract rider is not all roses, for if his performance drops off and he gets sacked, it's not likely that another factory will touch him, and that's the end of a career. And this, I think, is the big difference in rider attitude between Europe and the U.S.

At the Isle of Man and the Dutch TT, the riders were, almost without exception, withdrawn and sober. Whereas at an American race, everyone is pretty happy about having a race, and just about any sort of horseplay or good natured fun is apt to be going — until the flag drops.

Our riders probably take it less seriously, because, if they don't like their present arrangement, they can go out and buy a racing machine that is competitive. In Europe, however, there is no way an individual can buy a machine that will not be lapped on the average circuit. To see and hear Hailwood on the Hondas is an unforgettable experience, but it is rather sad to see really first-class riders, on the best racing motorcycles available to the public, being lapped.

This is not an editorial campaign to stamp out the "exotics." On the contrary; for without the factory multis that money cannot buy, the hundreds of thousands of spectators would not pay the hundreds of thousands of dollars to watch.

In Holland, there is a beautiful road race course near Assen that is used once a year for a motorcycle race. This year 120,000 people flocked to witness the battle of the giants, and enough money was collected at the gates to pay the riders, the salaries of the full-time office help at the year-round TT office in Assen, and the upkeep of the circuit.

The main industry of the Isle of Man is a motorcycle race where 150,000-plus people come to see the factory screamers. How does this affect us? Maybe we could do it like the Japanese, and have national and grand prix racing at the same circuit on the same day, run separately and under the rules for that particular event. This, it seems to me, is the best way for factory team managers to see local, and possibly future talent for his team.

ON the subject of production racing, the inhabitants of the Isle of Man are quite concerned over the fact that John Hartle took a street legal Triumph Bonneville around at 98 mph. For years these people have thought that a racing motorcycle must make noise, and when they are awakened at four-thirty a.m. every morning for a week and a half, they sort of stagger around until it is time to go to the office and put in the nine hours.

It seems they have been putting up with all of these things because of the money it brings in, until John, who is better now than ever before, made his little high-speed jaunt. Now it is apparent to the Manx folk that modern-day silencers may mean more sleep, and they plan to talk to the ACU about the possibility of all racing machines having mufflers.

Honda would have a job fitting six mufflers, but they do have the jump on the rest of the world in muffler technology.

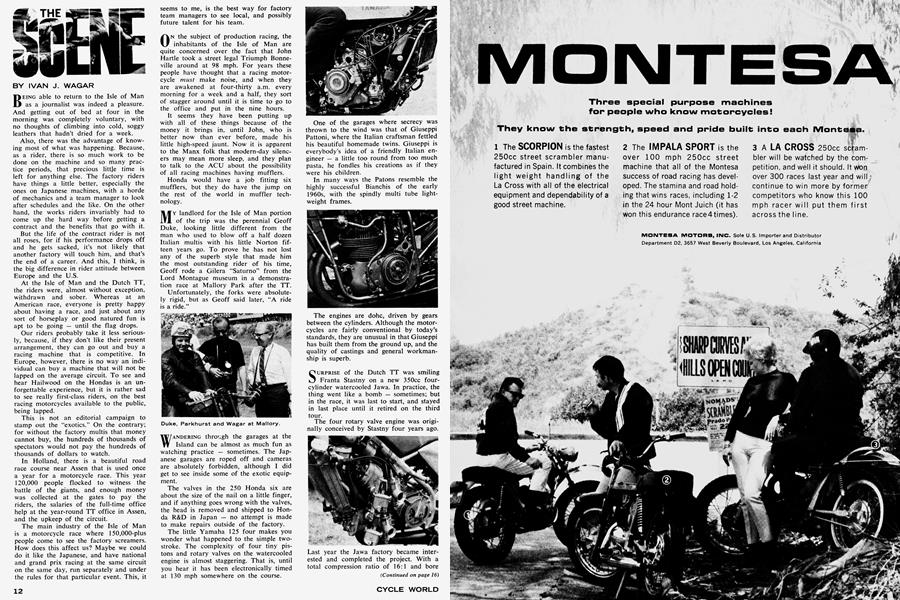

MY landlord for the Isle of Man portion of the trip was the perennial Geoff Duke, looking little different from the man who used to blow off a half dozen Italian multis with his little Norton fifteen years go. To prove he has not lost any of the superb style that made him the most outstanding rider of his time, Geoff rode a Gilera "Saturno" from the Lord Montague museum in a demonstration race at Mallory Park after the TT.

Unfortunately, the forks were absolutely rigid, but as Geoff said later, "A ride is a ride."

WANDERING through the garages at the Island can be almost as much fun as watching practice — sometimes. The Japanese garages are roped off and cameras are absolutely forbidden, although I did get to see inside some of the exotic equipment.

The valves in the 250 Honda six are about the size of the nail on a little finger, and if anything goes wrong with the valves, the head is removed and shipped to Honda R&D in Japan — no attempt is made to make repairs outside of the factory.

The little Yamaha 125 four makes you wonder what happened to the simple twostroke. The complexity of four tiny pistons and rotary valves on the watercooled engine is almost staggering. That is, until you hear it has been electronically timed at 130 mph somewhere on the course.

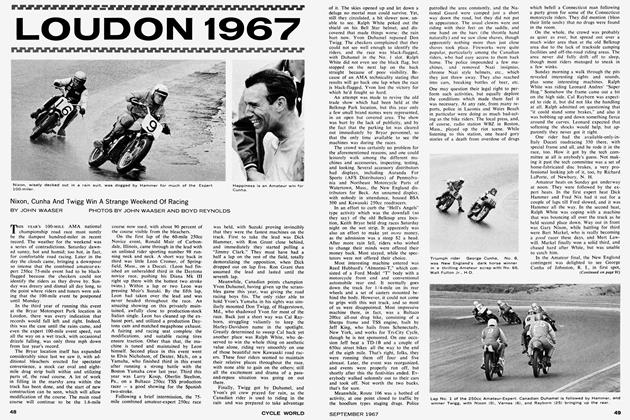

One of the garages where secrecy was thrown to the wind was that of Giuseppi Pattoni, where the Italian craftsman fettled his beautiful homemade twins. Giuseppi is everybody's idea of a friendly Italian engineer — a little too round from too much pasta, he fondles his creations as if they were his children.

In many ways the Patons resemble the highly successful Bianchis of the early 1960s, with the spindly multi tube lightweight frames.

The engines are dohc, driven by gears between the cylinders. Although the motorcycles are fairly conventional by today's standards, they are unusual in that Giuseppi has built them from the ground up, and the quality of castings and general workmanship is superb.

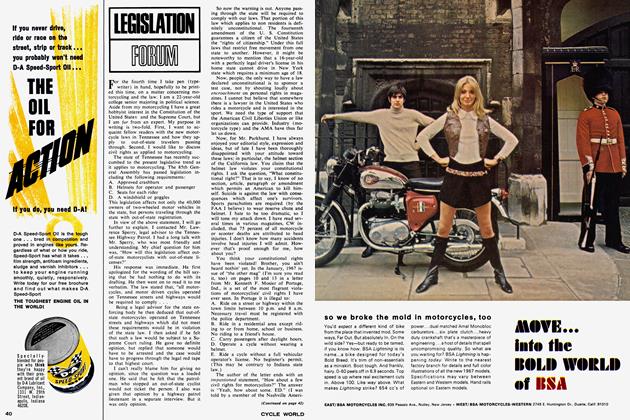

SURPRISE of the Dutch TT was smiling Franta Stastny on a new 350cc fourcylinder watercooled Jawa. In practice, the thing went like a bomb — sometimes; but in the race, it was last to start, and stayed in last place until it retired on the third tour.

The four rotary valve engine was originally conceived by Stastny four years ago.

Last year the Jawa factory became interested and completed the project. With a total compression ratio of 16:1 and bore stroke of 48 x 47, the engine is on power from 9,000 to 13,500 rpm. The factory claims 60 bhp through the seven-speed gearbox.

(Continued on page 16)

One reason for the poor performance in Holland might be the funny angle of the float chambers.

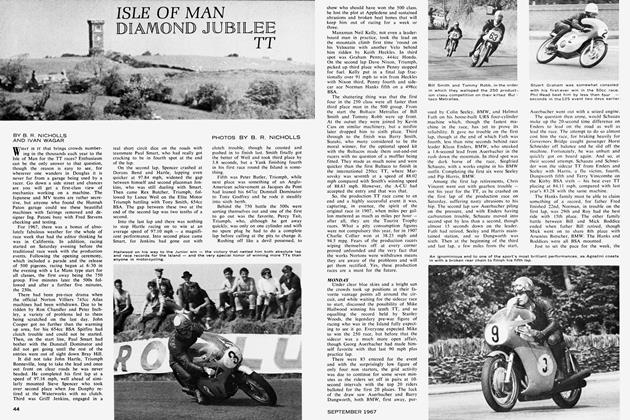

PROBABLY the busiest garage on the Isle of Man was Colin Seeley's. Colin, be-

sides still being active in sidecar racing, is the Manx Norton, AJS 7R and G 50 Matchless parts man. Last year, when the AMC factory officially went out of racing entirely, Seeley bought the complete inventory of racing parts.

He was also fortunate to acquire Bill Wright, who has been in charge of racing spares at the Island longer than most of us have been around. Bill is a full-time employee of the company, in addition to two former factory mechanics.

Colin is busy having new parts made to original specifications, such as: cylinders, crankcases, cylinderheads and the like. For gearboxes, he relies on Schaftleitner internals for AMC cases, as no one wants a four-speed box now, anyway.

(Continued on page 18)

In the back of the shop, the mechanics were working on the Seeley Matchless to be ridden by John Blanchard. Some two and a half inches lower at the steering head, over a standard Matchless, and a good deal lighter, the machine is one of the more competitive singles around.

Although Colin is an extremely energetic individual, the pressure of the spares service, the repair shop, Blanchard's machine and his own racing, led to all sorts of headaches.

Yamaha's racing activity in the U.S. has just received a shot in the arm with the recent announcement that former Warranty Manager Tony Murphy is now Director of Competition for Yamaha International.

Tony began racing in 1961 as my protege, and almost overnight became an AFM sensation. Starting on private Ducatis and 7Rs he went on to the Honda four, RD 56 Yamaha and Manx Norton, scoring an enviable string of victories.

After joining Yamaha International, Tony settled down to racing the official TD-ls, and in 1965, won the AMA national road race at Loudon, New Hampshire. His duties mean the end of a brilliant career, but he is very eager to get on with the task of race "gaffer."

It is hoped that Yamaha will now revive the 350 program. The machines have been dormant since Daytona, although in the hands of Murphy and Mike Duff they showed tremendous potential, and I feel with only slightly more development they will be the bikes to beat.