KING OF THE FLAT TRACKS

J.L.BERDSLEY

SINCE THE BEGINNING of organized motorcycle competition in the United States, outstanding performers and great champions have appeared in all fields, and most of them were great on the mile and half-mile dirt tracks too; but on flat tracks there was one who was immortal. When the pro riders turned loose real horsepower on the horse tracks, it sparked unforgettable duels of daredevil speed — meets that were epics of two-wheel sport — and in this savage competition among the stars of professional racing, Gene Walker rode out his spectacular career.

In his day Eugene E. “Gene” Walker knew no peer as a dirt track sprinter. He outrode the all-time greats on nearly every major track in the country, and set scores of national and local records on the championship trail. Walker was a dirt track “specialist” and rarely rode in any other events, though he did score wins on both the board auto speedways and road race courses.

He had a knack of analyzing any track after a few practice laps, and on a skillfully-tuned machine he murdered the opposition. If the groove was on the inside he would barrel into the turns with his head skimming the top rail of the fence; or perhaps it would be on the straights that Walker would pour on the coal and shake off pursuit. Riders who followed him every foot of the entire circuit never found his secret. They could have saved this effort though; there’s no way of figuring out genius.

Gene Walker, a born race rider, first saw daylight on November 17, 1893, at Birmingham, Alabama. At 17 he owned his first belt-driven motorcycle, but soon traded it for a new Indian machine. In 1912, he found an excuse to be in the saddle constantly by becoming a Special Delivery messenger for the Post Office. When Walker roared up to someone's door with popping exhausts and a letter, all the neighbors knew it; but every bit of this practice was useful. That same year he entered a 5-mile race at the Alabama State Fair and won it easily. After that he was hooked by the speed bug.

One of the south’s largest Indian motorcycle dealers, Bob Stubbs, gave him a job, and being a red-hot race fan, Stubbs coached Walker and supplied him with a new 8-valve Indian race job direct from the factory. Eventually, Gene reached the professional ranks when he entered a onehour race at Birmingham in 1914. On his first lap he broke the track record, but he didn’t win the race. Even with his natural ability, Walker had a lot to learn, and the Hendee Manufacturing Company, builders of the famous Indian machines at Springfield, Mass., accepted him in their testing department in 1915, where a liberal education in mechanics was given him.

After basic training in how the Indian race jobs were designed and built, Walker was picked as the jockey to ride these steel thoroughbreds in the acid test of racing competition, where reputations were won and lost — but the results were terrific both for Walker and the Indian.

Gene Walker’s career was launched at an F.A.M. championship meet on July 10, 1915, at Saratoga, New York, where bigname riders attracted a crowd from all over New England. The huge throng was

amazed to see rookie Gene take the lead in the 5-mile National, hotly pursued by Teddy Carroll (Indian), with Excelsior stars, Glen Stokes and Bob Perry, right behind. Walker lost the lead momentarily but with a sensational burst took over again and finished on top in 4:28 3/5, the fastest five miles ever seen on this track. He scored a second and a third in other events there.

He was not very active in 1916, and went into special army ordnance work when the first World War had to be fought and won. But in the great racing boom following the war’s end, Gene soared to national fame on the nation’s dirt tracks. In 1919 he won four out of the nine National Championships, at one, five, ten and 15 miles, and shattered the mile circular track record three times.

One of his biggest days was June 8, at the Lakewood Park mile in Atlanta, Georgia, where he defeated local favorites Nemo Lancaster and Tex Richards for the Southern Dirt Track Championship. So great an upset was his victory that it had to be rerun later before the Dixie speed fans could believe it! For three months the Georgia motorcycle race fans had been debating Walker’s upset of their local favorites, and when the Lakewood Park officials scheduled another Southern Championship meet on September 13, 1919, over 9000 flocked to the track — some from points 700 miles distant.

When Walker, Lancaster and Richards roared into the 5-mile race for the title, every fan was on his feet and cheering. Lancaster got away in front and Walker stalked him for three laps, waiting for the right spot, and in the home stretch on the third round he shot ahead with a tremendous burst of speed, directly in front of the grandstand. Lancaster tried hard for the next two circuits but was still half a length behind at the finish.

Harley stars Ralph Hepburn and AÍ “Shrimp” Burns were formidable opponents of Walker and Fred Nixon on Indians in the one-mile championship, and it took a sizzling new track record by Walker of 46 3/5 to capture this first heat.

In the second mile heat Harley-Davidson greats Otto Walker (no relation to Gene) and Red Parkhurst went to the post against Nemo Lancaster and Tex Richards on Indians, with Lancaster winning in 48 seconds flat. The third heat matched the two top men in the previous heats, and Gene Walker streaked around for another mile record of 46 seconds and the title.

Against the nation’s hottest riders, Walker proceeded to trim the big names in two successive 5-mile events at 3:57 and a fraction; and in the 25-mile feature he dueled with the sensational “Shrimp” Burns for many miles until Bums had a wheel collapse, giving Walker another sensational win.

Probably no rider ever scored as big a triumph in any single day as Walker did here. He won six out of seven events and was second in the other, over top competition; set the year’s fastest times for all distances contended; won three National Championships: 1-5-25 miles with gold medals on each, and five other trophies; the Southern Championship, plus $650 in cash, which represented a bonus as the pro riders were salaried. Walker’s tremendous one-man performance won him unlimited publicity both in and outside motorcycle circles.

The most mammoth motorcycle meet in history took place at the famous Sheepshead Bay Speedway, Brooklyn’s 2-mile autodrome, on October 11, 1919, when 40,000 were in the stands to see the kings of two-wheel speed duel for top honors.

The Harley team, as usual, was “up” for the longer events, and the 100-Mile Speedway Championship went to AÍ “Shrimp” Burns riding one of the Milwaukee-built machines. Ray Weishaar sent his Harley around the big saucer for a 50-mile world record of 32:57 2/5; but then the King of the Sprinters stepped into the arena, and Gene was in at his favorite distance — 10 miles — running against Harley’s two winners, plus the great Red Parkhurst and Otto Walker. Indian had Fred Nixon and Teddy Carrol going for them as insurance, but none of these hot-handlebar twisters could stay with Gene as he burned up the boards, away out front, in a sizzling 6:19 2/5 for another National title and record. And then he was off to San Angelo, Texas for three days of racing on October 27-30-31, and three more victories at 3, 5 and 10 miles.

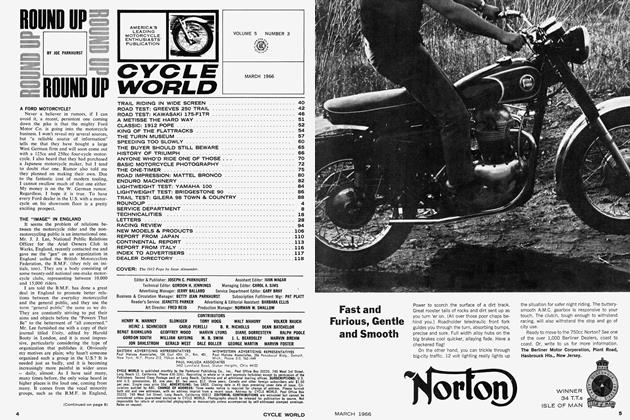

With the triumphant year of 1919 to give him confidence, Gene was eager for the 1920 season opening, and the pursuit of more victories, records and championships. It began at the Arizona State Fair track at Phoenix, January 25, against an all-star field of riders. Qualifying times for the 25-mile feature foreshadowed the toughness of the competition: AÍ “Shrimp” Burns on the Indian team with Walker, broke the track record with a lap in 42 2/5; Walker was second at 45 3/5; Bill Church, Excelsior, 47; Joe Wolters, Excelsior, 46 2/5; Red Parkhurst, H-D, the same; and Ralph Hepburn, H-D, 48.

(Continued on page 56)

Bums beat out his teammate, Walker, by half a length to win a 5-mile event, and did it again by a few feet in the 10mile Free-For-All. The 15-mile Free-ForAll turned into a three-way battle between Walker, Bums and Hepburn, but Walker squeezed out a win by a few feet in 11:57. Jim Davis was up as a third Indian team rider in the 25-mile State Championship, and he, Walker and Burns ran away with this contest; Gene topped the trio for a new track record of 19:32 3/5.

After Red Parkhurst put Harley-Davidson on top of the speed world with Flying Mile records at Daytona Beach, Florida, in the spring of 1920, the Indian company groomed a special 8-valve 61-inch machine, and put the King of the Sprinters in the saddle, for there was nobody in the gofast business who could fly like Gene Walker. He had set circular mile marks several times, but here was a flat-out mile with no curves, and it looked good to Gene.

On April 12, 1920 there was a blur of red as Walker shot his Indian over the silver Daytona sands to the tune of a mile at 114.17; two miles at 111.17; and five miles at 108.71 mph, all better than the Harley marks made with a 68-inch motor. Herb McBride, and Walker, together set 25 professional and stock class records between April 12 and 15, and one was a two-way average over the mile by Walker of 34.70 seconds for the first American Flying Mile record accepted by the international F.I.C.M. in Europe as a World record.

Now the “Fastest Man On Two Wheels,” as the billboards shouted, Walker was a huge gate attraction. Fans at the 50-Mile Road Race Championship run on a 3-mile course formed from part of the famed Vanderbuilt Cup auto track at Savannah, Georgia, April 26, 1920, were the first to see Walker in action. His old rival, Nemo Lancaster, had entered, but it was Indianmounted Len Buckner who gave him a terrific battle, losing the 50-mile championship to Walker by just one second.

At Philadelphia, Gene rode out a 10mile record of 7:43 2/5 on June 19, and then at Rockford, Illinois, “cleaned house” in a two-day meet July 24-25, where his fast 61-inch Indian carried him to wins jn two 5-mile events, two 10-mile, and a 25mile feature; plus the 2-mile National Championship.

The 30.50 cubic inch machines were being called too fast for half-mile ovals in 1920, but Gene Walker wasn’t complaining. At Akron, Ohio, August 1, he took down the National one-mile and two-mile titles in this class. Then, all the top riders were on hand for the speed festival at the North Randall mile track in Cleveland, Ohio, scene of much motor speed over the years, and September 19 was another redletter day at Randall. For the second time in his career, Walker tore through a new official mile dirt track record of 45 2/5 in the 61-inch solo class. He took the 5mile event in a record of 3:51; but a month later, at Readville, Mass., he clipped one-fifth of a second off this mark.

He tried for a new record in a special run during a meet at Belmont Park, Narbeth, Pa., on October 16, but missed with a 48-second lap. Still he lived up to his advance billing by streaking to the 10-mile Keystone State Championship, and winning the M.&A.T.A. Middle-Atlantic trophy in 22:22.00 against some of the best riders in the east.

Again in 1921, Gene began burning up the half-milers on his 30.50 Indian. Officials were toying with the idea of banning these machines on half-miles, so Gene wanted to make hay while he could. He went into action at Greeley, Colorado, May 30, 1921, where he copped the 3-mile National record in 3:18, and won the 10mile event. At Mansfield, Ohio, he trimmed his 3-mile mark on a half-mile track to 3:11 3/5 on August 25; and at Akron he lowered the 2-mile record to 2:14 3/5. Winding up his triumphant 1921 season on November 8 at the St. Louis mile track, Walker shattered three more records at 1-5-10 miles.

The next season Walker continued to make the critics of the 30.50 bikes, and their “too dangerous” clamor, sound silly. The officials weren’t buying it, either. At South Bend, Indiana, on September 3-4, 1922, Gene won a 5-mile race on opening day, and on the second lowered his own 3-mile record to 3:02 2/5; and put up a new 5-mile time for half-milers of 5:07 3/5.

Before it was paved, the State Fair Park mile at Milwaukee was a popular motorcycle speed rendezvous, and Walker won the 25-mile feature there in 1922 on his fast 30.50 Indian. On a 61-incher he took a 10-mile heat and was third in the 25mile feature. A 5-mile heat went to Walker at the Syracuse, New York State Fair that year, and then he broke the one-mile 30.50 record on half-mile circuits twice: first at Singac, N. Y. on Sept. 9, and at Springfield, ' Mass., Oct. 12, where he did two laps in 1:00 2/5.

In 1923 Gene teamed up with Johnny Seymour after the Readville, Mass, races on July 4th. They had first met on Walker’s Colorado trip in 1920, when Seymour was employed by a Denver agency. Walker secured a machine from the Indian factory for Seymour for the 1921 Dodge City 300-mile road race on July 4th, and Seymour’s first big-time start was a second in the “Coyote Classic” to Ralph Hepburn, who won in sensational style.

Walker closed another successful season in 1923 by collecting the 5-mile National at Syracuse, N. Y. in a record 3:47 on Sept. 15, as well as the 25-mile National, at 18:09 1/6 in the 61-inch solo class. At Milwaukee, on August 12, he was top man in the 10-mile National, while his racing partner, Johnny Seymour, salted away the 30.50 National 10-mile honors.

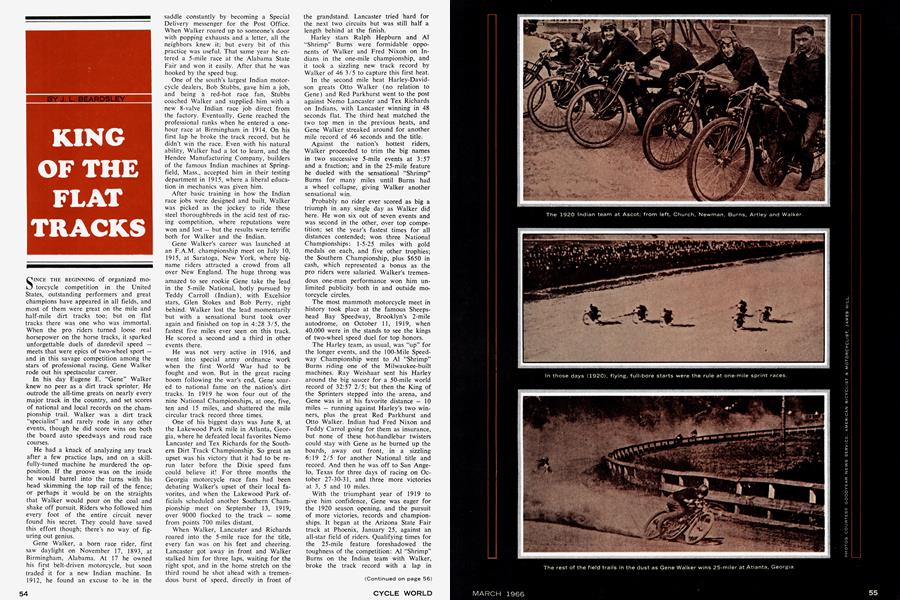

The new Ascot track opened January 6, 1924 in Los Angeles, with former West Coast racing great, Paul Derkum, in charge of motorcycle promotion. Here Southern California fans saw motorcycle speed and red-hot racing never surpassed anywhere — and Gene Walker was at his brilliant best. In a one-lap Helmet Dash (5/8-mile), Walker nosed out Ralph Hepburn, holder of the world’s circular mile dirt record, in a photo finish at 37 2/5.

Over 20,000 fans flocked to fill the stands to capacity in February and Walker swept the card. This included another hairraising Helmet Dash when Walker cut the lap record to 32 seconds flat, one second faster than the auto mark! His competition in the 5-mile National that he won was Hepburn (H-D), second; and Johnny Krieger (Indian) took third over Joe Petrali (Indian), by six inches. The pace in the ten-lap Ascot Handicap was so hot that Ray Weishaar went down in the 4th round, and Walker was ahead the next time around, with Johnny Krieger chasing him relentlessly until his engine blew up, and he spilled but was unhurt. Walker’s winning time was 5:27 4/5 — he was the Ascot champ in points with five firsts, two seconds, and one third — but he had won his last race on the coast.

In April he returned to his home, and wife, in Birmingham; and whether from some vague premonition, or just as a friendly act, he left his favorite 30.50 Indian behind in possession of his pal, Johnny Seymour. On May 30, 1924, he won three out of four races on his 61-inch bike at Huntington, West Virginia, and then moved on to his next date at Stroudsburg, Pennsylvania — but this one he would never fill.

What happened there nobody saw; but as usual, Gene went out for some practice laps to size up the course the morning of the meet. Later, some track workmen found him lying unconscious in a field, and his wrecked machine was near a hole in the fence. Rushed to the Rosencrans Hospital, at East Stroudsburg, he died on June 21, 1924 of head and internal injuries, and motorcycling had lost one of its most colorful and gifted sportsmen.

Within a month the Indian company announced cancellation of all future factory-sponsored racing in deference to Walker’s memory. For a concern whose reputation had been forged on the race tracks, this was a tremendous concession and tribute to the sprint champion, but no one could have deserved it more. ■