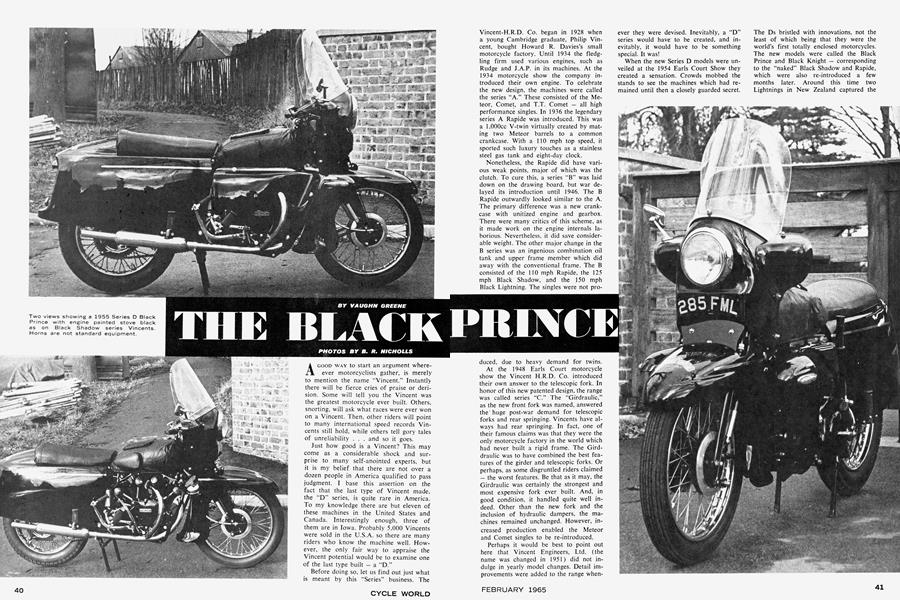

THE BLACK PRINCE

VAUGHN GREENE

A GOOD WAY to start an argument whereever motorcyclists gather, is merely to mention the name “Vincent.” Instantly there will be fierce cries of praise or derision. Some will tell you the Vincent was the greatest motorcycle ever built. Others, snorting, will ask what races were ever won on a Vincent. Then, other riders will point to many international speed records Vincents still hold, while others tell gory tales of unreliability . . . and so it goes.

Just how good is a Vincent? This may come as a considerable shock and surprise to many self-anointed experts, but it is my belief that there are not over a dozen people in America qualified to pass judgment. I base this assertion on the fact that the last type of Vincent made, the “D” series, is quite rare in America. To my knowledge there are but eleven of these machines in the United States and Canada. Interestingly enough, three of them are in Iowa. Probably 5,000 Vincents were sold in the U.S.A. so there are many riders who know the machine well. However, the only fair way to appraise the Vincent potential would be to examine one of the last type built - a “D.”

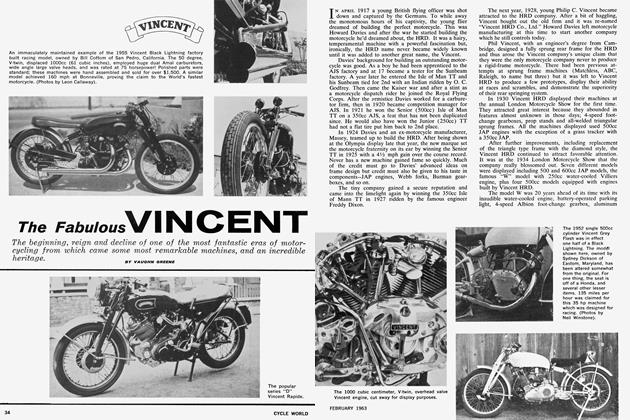

Before doing so, let us find out just what is meant by this “Series” business. The Vincent-H.R.D. Co. began in 1928 when a young Cambridge graduate, Philip Vincent, bought Howard R. Davies’s small motorcycle factory. Until 1934 the fledgling firm used various engines, such as Rudge and J.A.P. in its machines. At the 1934 motorcycle show the company introduced their own engine. To celebrate the new design, the machines were called the series “A.” These consisted of the Meteor, Comet, and T.T. Comet — all high performance singles. In 1936 the legendary series A Rapide was introduced. This was a LOOOcc V-twin virtually created by mating two Meteor barrels to a common crankcase. With a 110 mph top speed, it sported such luxury touches as a stainless steel gas tank and eight-day clock.

Nonetheless, the Rapide did have various weak points, major of which was the clutch. To cure this, a series “B” was laid down on the drawing board, but war delayed its introduction until 1946. The B Rapide outwardly looked similar to the A. The primary difference was a new crankcase with unitized engine and gearbox. There were many critics of this scheme, as it made work on the engine internals laborious. Nevertheless, it did save considerable weight. The other major change in the B series was an ingenious combination oil tank and upper frame member which did away with the conventional frame. The B consisted of the 110 mph Rapide, the 125 mph Black Shadow, and the 150 mph Black Lightning. The singles were not produced, due to heavy demand for twins.

At the 1948 Earls Court motorcycle show the Vincent H.R.D. Co. introduced their own answer to the telescopic fork. In honor of this new patented design, the range was called series “C.” The “Girdraulic,” as the new front fork was named, answered the huge post-war demand for telescopic forks and rear springing. Vincents have always had rear springing. In fact, one of their famous claims was that they were the only motorcycle factory in the world which had never built a rigid frame. The Girddraulic was to have combined the best features of the girder and telescopic forks. Or perhaps, as some disgruntled riders claimed — the worst features. Be that as it may, the Girdraulic was certainly the strongest and most expensive fork ever built. And, in good condition, it handled quite well indeed. Other than the new fork and the inclusion of hydraulic dampers, the machines remained unchanged. However, increased production enabled the Meteor and Comet singles to be re-introduced.

Perhaps it would be best to point out here that Vincent Engineers, Ltd. (the name was changed in 1951) did not indulge in yearly model changes. Detail improvements were added to the range whenever they were devised. Inevitably, a “D” series would have to be created, and inevitably, it would have to be something special. It was!

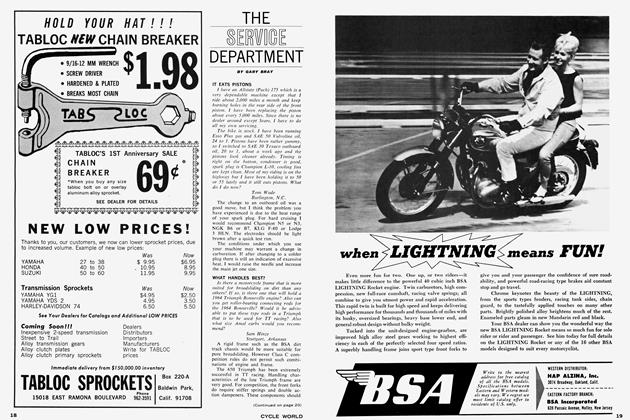

When the new Series D models were unveiled at the 1954 Earls Court Show they created a sensation. Crowds mobbed the stands to see the machines which had remained until then a closely guarded secret. The Ds bristled with innovations, not the least of which being that they were the world’s first totally enclosed motorcycles. The new models were called the Black Prince and Black Knight — corresponding to the “naked” Black Shadow and Rapide, which were also re-introduced a few months later. Around this time two Lightnings in New Zealand captured the world’s speed records for solo and sidecar. Therefore, it was a double shock when Vincent Engineers, Ltd. shut down production in 1955, with fewer than 500 Series Ds having been built at the Stevenage works. (Only two D singles were produced — a “naked” Comet, and its clothed counterpart, the Victor.)

So much for history. Was the D series really any better than the Ai the B, and the C? Indeed, many claimed the D was a mistake, a retrograde step which drove the company out of business. Let us compare a D to a C and find out how good the last Vincents really were.

At the time the Ds were being developed, racing fairings were in their infancy. Nevertheless, far-seeing types claimed fairings would some day be commonplace on all motorcycles since they increase speed, cut down gas consumption and, above all, protect the rider from the elements. The fairings used on the Prince and Knight were developed primarily to shield the rider from wind and rain. Indeed, the sensation while riding one of these machines is like being in a sports car, and goggles can be thrown away. Leg shields, hand muffs, and an aerodynamically designed windshield enable a rider to take long trips in ordinary clothing without discomfort.

Although rider protection was the aim of the fairings, a number of other advantages were incidental dividends. For example, the leg shields act as air ducts, and the engine actually runs cooler. Another advantage: in the event of a crash, the frontal fairings act as crash pads, protecting the ride like the padded dash of a car. Cleaning up time is reduced to about one minute’s use of a damp rag. This was an idea appreciated by the really hard, fast Vincent rider who didn’t care to spend his Sunday afternoons polishing a twowheeled mountain of chrome. Speaking of chrome — it was virtually eliminated (except for muffler and handlebar), as were all decorations. True, many riders apparently like to spend their time polishing innumerable little bits and pipes. But Phil Vincent felt it was about time the old adage that “a motorcycle is the only vehicle with its guts hanging out” was changed. A further benefit of hiding the engine and frame was that the unit price could be lowered. Expensive polishing and plating could be eliminated from parts that usually require these operations for the sake of appearance.

In regards to accessibility, the fairings present no problems. The two engine shields are held by three quick-disconnect Dzus fasteners each. The rear shell pivots up to be retained by a prop, just as with a car hood. The dual seat also pivots up, to reveal a large tool compartment molded into the rear shell. Incidentally, future plans had intended that large fiberglass saddlebags would be available, that would screw into fittings on the shell.

Theories may be all right, but how did the fairings stand up in actual practice? Most riders reported that where they used to do 70 mph, they now found the same impression of speed at 90 mph. Handling in strong winds improved, due to the aerodynamically designed shell. No longer were clumsy gauntlets and heavy leathers required. Further, the machine was quieter, and far more comfortable. The reason for the latter was not only because of the fairings, but for a number of other reasons.

In the interests of a more comfortable ride, softer springs were used together with softer shocks. The dual seat, for the first time, was fully sprung. Larger section tires also helped, as did Mark III cams which were quieter than the former pattern. Again, this sort of'radical change alienated some of the old guard die-hards — but you can’t have things both ways.

In addition to full fairings, larger tires, softer ride, and coil ignition, still more radical changes were made. The complicated Vincent front stands were scrapped and replaced by an ingenious leveroperated center stand. When riding, the lever lies parallel with the rider’s left foot. However, on giving the lever a gentle tug, the bike virtually rolls itself onto the stand. The stoplight was now operated by the front brake, since most riders use it at high speeds anyway. Other changes included: a better voltage regulator and headlight, a more powerful generator, and a leakproof battery. Also utilized were leakproof dampers by Armstrong, better grade clutch and brake linings, a larger gas tank, louder horn, Monobloc carburetors, and redesigned steering damper, engine shock absorber, primary chain tensioner, gear change mechanism, clutch chamber sealing, and engine breather. I might add that many of these later parts are definite improvements, and should be added by owners of Series B and C Vincents.

Thus it was that the hairy, temperamental Vincent of old was tamed down to a smooth road burner that could have had fascinating possibilities on our long distance freeways. But, too late! Too late! The gods of finance had struck down this futuristic machine which even today has no equal. Perhaps it was just and fitting, when the movie “1984” was being filmed, that 12 Vincent Black Prince motorcycles were included in the props. •

Footnote:

Many readers by now have, no doubt, a desire to actually ride one of these mythical beasts. The writer recently satisfied ten years of a similar desire by importing a D Vincent from England. There are perhaps fifty D Vincents left lying around in various shops in England. After vainly scouting, by mail, a number of these establishments, 1 finally chose one of the largest dealers in London. They had a selection of D Rapides, Shadows, Princes, and two Knights. I chose one of the Knights at $500. The “naked” models run less, and the Prince about $150 more. The Knight was described as being in “average condition for the year.” A further $150 was sent to the shop, which then paid to have the bike crated for ocean shipment and shipped by the Royal Mail Lines.

Frankly, 1 was somewhat disappointed. The machine certainly looked neglected. The tank and engine had been gone over with house paint, and both engine shields needed some cracks mended. It was obvious the former owner had been a bit of a kook, and worse, had apparently been lugging about a great dirty sidecar at one time. Rust and dirt were abundant.

Was it worth it? To me, yes — perhaps to another, no. There are still expensive items to get, not the least of which is the license. There is a great deal of restoration to do. But if the end result is truly a Knight of the road, it will be worth it. 0