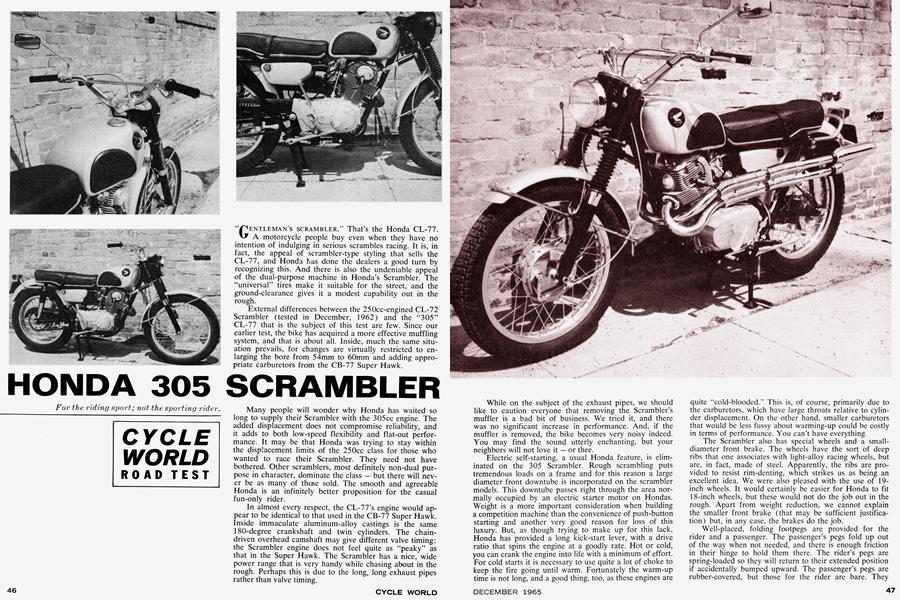

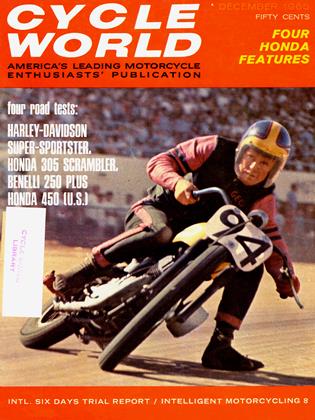

HONDA 305 SCRAMBLER

For the riding sport; not the sporting rider

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

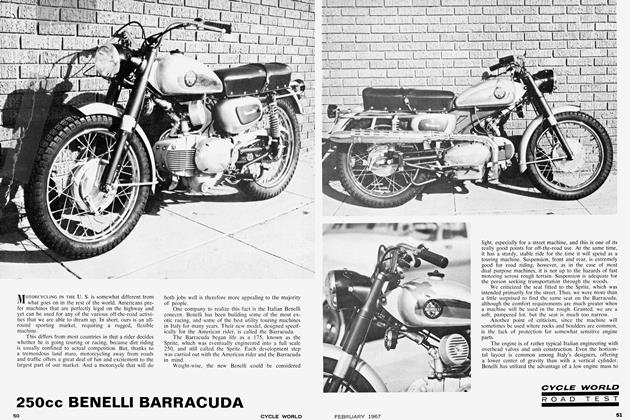

GENTLEMAN'S SCRAMBLER." That's the Honda CL-77. A motorcycle people buy even when they have no intention of indulging in serious scrambles racing. It is, in fact, the appeal of scrambler-type styling that sells the CL-77, and Honda has done the dealers a good turn by recognizing this. And there is also the undeniable appeal of the dual-purpose machine in Honda's Scrambler. The "universal" tires make it suitable for the street, and the ground-clearance gives it a modest capability out in the rough.

External differences between the 250cc-engined CL-72 Scrambler (tested in December, 1962) and the "305" CL-77 that is the subject of this test are few. Since our earlier test, the bike has acquired a more effective muffling system, and that is about all. Inside, much the same situation prevails, for changes are virtually restricted to enlarging the bore from 54mm to 60mm and adding appropriate carburetors from the CB-77 Super Hawk.

Many people will wonder why Honda has waited so long to supply their Scrambler with the 305cc engine. The added displacement does not compromise reliability, and it adds to both low-speed flexibility and flat-out performance. It may be that Honda was trying to stay within the displacement limits of the 250cc class for those who wanted to race their Scrambler. They need not have bothered. Other scramblers, most definitely non-dual purpose in character, dominate the class — but there will never be as many of those sold. The smooth and agreeable Honda is an infinitely better proposition for the casual fun-only rider.

In almost every respect, the CL-77's engine would appear to be identical to that used in the CB-77 Super Hawk. Inside immaculate aluminum-alloy castings is the same 180-degree crankshaft and twin cylinders. The chaindriven overhead camshaft may give different valve timing: the Scrambler engine does not feel quite as "peaky" as that in the Super Hawk. The Scrambler has a nice, wide power range that is very handy while chasing about in the rough. Perhaps this is due to the long, long exhaust pipes rather than valve timing.

While on the subject of the exhaust pipes, we should like to caution everyone that removing the Scrambler's muffler is a bad bit of business. We tried it, and there was no significant increase in performance. And, if the muffler is removed, the bike becomes very noisy indeed. You may find the sound utterly enchanting, but your neighbors will not love it — or thee.

Electric self-starting, a usual Honda feature, is eliminated on the 305 Scrambler. Rough scrambling puts tremendous loads on a frame and for this reason a large diameter front downtube is incorporated on the scrambler models. This downtube passes right through the area normally occupied by an electric starter motor on Hondas. Weight is a more important consideration when building a competition machine than the convenience of push-button starting and another very good reason for loss of this luxury. But, as though trying to make up for this lack, Honda has provided a long kick-start lever, with a drive ratio that spins the engine at a goodly rate. Hot or cold, you can crank the engine into life with a minimum of effort. For cold starts it is necessary to use quite a lot of choke to keep the fire going until warm. Fortunately the warm-up time is not long, and a good thing, too, as these engines are quite "cold-blooded." This is, of course, primarily due to the carburetors, which have large throats relative to cylinder displacement. On the other hand, smaller carburetors that would be less fussy about warming-up could be costly in terms of performance. You can't have everything.

The Scrambler also has special wheels and a smalldiameter front brake. The wheels have the sort of deep ribs that one associates with light-alloy racing wheels, but are, in fact, made of steel. Apparently, the ribs are provided to resist rim-denting, which strikes us as being an excellent idea. We were also pleased with the use of 19inch wheels. It would certainly be easier for Honda to fit 18-inch wheels, but these would not do the job out in the rough. Apart from weight reduction, we cannot explain the smaller front brake (that may be sufficient justification) but, in any case, the brakes do the job.

Well-placed, folding footpegs are provided for the rider and a passenger. The passenger's pegs fold up out of the way when not needed, and there is enough friction in their hinge to hold them there. The rider's pegs are spring-loaded so they will return to their extended position if accidentally bumped upward. The passenger's pegs are rubber-covered, but those for the rider are bare. They have some pressed-in cleats that are supposed to give a more secure footing; these did not fully realize the designer's intent.2

As on the touring Honda (and indeed on all Hondas), very large and effective air filters are provided. These have been tucked away under the seat and are covered with trim metal panels — said panels also enclosing the battery and tool kit compartment. The battery is necessary: Honda's Scrambler is delivered with complete lighting equipment. That, and the headlight-mounted speedometer, further emphasize the dual-purpose character of the machine.

Riding the Honda Scrambler out in the rough is pleasant provided one does not get completely carried away. The steering needs a bit more rake, we think, as the front wheel does have a tendency to flip about. On the credit side, the forks do have a lot of travel, as does the rear suspension, and you will not bottom the suspension under any but the most severe conditions even when carrying a passenger. Of course, for steep hills and soft sand, the "universal" tire-treads do not get enough bite. Unless these are changed, avoid the difficult spots; and if they are changed to knobbies, don't try anything very brisk on pavement. For hard riding, you might want to try a slightly heavier oil in the strut-type hydraulic steering damper. That would help hold the front-end waggle within reasonable limits, or so it would seem.

For a machine of its displacement, the Honda Scrambler is decidedly heavy, but the weight is not as much a handicap as it at first seems. With experience, you will find that the Honda can be yanked about rather neatly — even though it cannot match the agility of a pure competition scrambles motorcycle. Where the weight does make a difference that counts is in its performance. Whatever it was that has given our test bike such good low-speed running ability seems to have cut the horsepower, and the engine will not push this rather heavy scrambler down the road in more than moderately-rapid fashion. We have ridden slower motorcycles, some with more displacement than the Honda; it's just that we have come to expect Hondas to be fast.

Despite our criticisms, we liked the Honda Scrambler. It is not the best scrambler in the world, or the best touring bike. What it does offer is a surprisingly good ridingto-work motorcycle that will not balk at excursions out in the boondocks. That is precisely what a lot of riders want, and that is why so many Honda Scramblers are seen on our streets.

HONDA

305 CL-77

SPECIFICATIONS

$72

PERFORMANCE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue