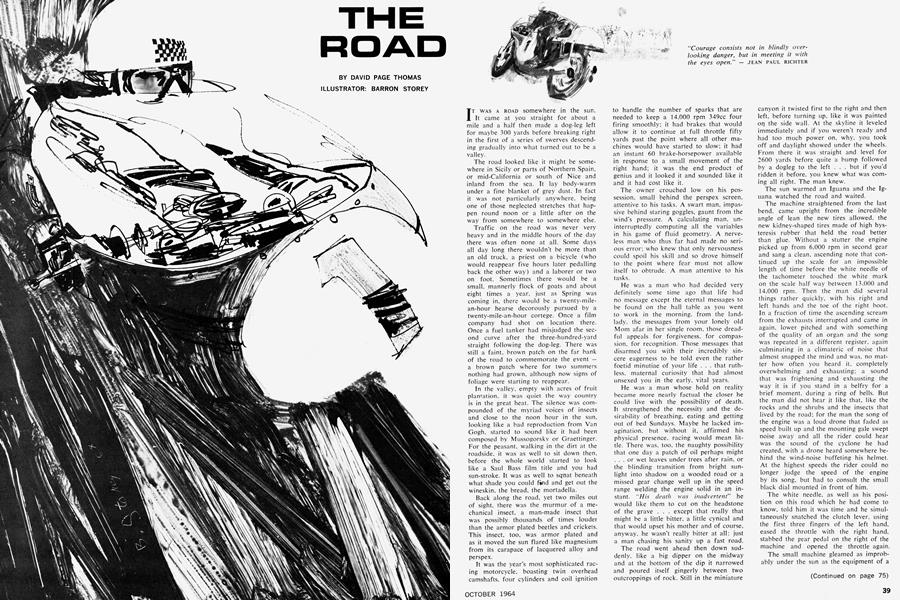

THE ROAD

DAVID PAGE THOMAS

"Courage consists not in blindly overlooking danger, but in meeting it with the eyes open.''

JEAN PAUL RICHTER

IT WAS A ROAD somewhere in the sun. It came at you straight for about a mile and a half then made a dog-leg left for maybe 300 yards before breaking right in the first of a series of swerves descending gradually into what turned out to be a valley.

The road looked like it might be somewhere in Sicily or parts of Northern Spain, or mid-California or south of Nice and inland from the sea. Tt lay body-warm under a fine blanket of grey dust. In fact it was not particularly anywhere, being one of those neglected stretches that happen round noon or a little after on the way from somewhere to somewhere else.

Traffic on the road was never very heavy and in the middle hours of the day there was often none at all. Some days all day long there wouldn't be more than an old truck, a priest on a bicycle (who would reappear five hours later pedalling back the other way) and a laborer or two on foot. Sometimes there would be a small, mannerly flock of goats and about eight times a year, just as Spring was coming in. there would be a twenty-milean-hour hearse decorously pursued by a twenty-mile-an-hour cortege. Once a film company had shot on location there. Once a fuel tanker had misjudged the second curve after the three-hundred-yard straight following the dog-leg. There was still a faint, brown patch on the far bank of the road to commemorate the event — a brown patch where for two summers nothing had grown, although now signs of foliage were starting to reappear.

In the valley, empty with acres of fruit plantation, it was quiet the way country is in the great heat. The silence was compounded of the myriad voices of insects and close to the noon hour in the sun. looking like a bad reproduction from Van Gogh, started to sound like it had been composed by Mussogorskv or Graettinger. For the peasant, walking in the dirt at the roadside, it was as well to sit down then, before the whole world started to look like a Saul Bass film title and you had sun-stroke. It was as well to squat beneath what shade you could find and get out the wineskin, the bread, the mortadella.

Back along the road, yet two miles out of sight, there was the murmur of a mechanical insect, a man-made insect that was possibly thousands of times louder than the armor plated beetles and crickets. This insect, too. was armor plated and as it moved the sun flared like magnesium from its carapace of lacquered alloy and perspex.

It was the year's most sophisticated racing motorcycle, boasting twin overhead camshafts, four cylinders and coil ignition to handle the number of sparks that are needed to keep a 14.000 rpm 349cc four firing smoothly; it had brakes that would allow it to continue at full throttle fifty yards past the point where all other machines would have started to slow; it had an instant 60 brake-horsepower available in response to a small movement of the right hand; it was the end product of genius and it looked it and sounded like it and it had cost like it.

The owner crouched low on his possession, small behind the perspex screen, attentive to his tasks. A swart man, impassive behind staring goggles, gaunt from the wind's pressure. A calculating man, uninterruptedly computing all the variables in his game of fluid geometry. A nerveless man who thus far had made no serious error; who knew that only nervousness could spoil his skill and so drove himself to the point where fear must not allow itself to obtrude. A man attentive to his tasks.

He was a man who had decided very definitely some time ago that life had no message except the eternal messages to be found on the hall table as you went to work in the morning, from the landlady, the messages from your lonely old Mom afar in her single room, those dreadful appeals for forgiveness, for compassion, for recognition. Those messages that disarmed you with their incredibly sincere eagerness to be told even the rather foetid minutiae of your life . . . that ruthless, maternal curiosity that had almost unsexed you in the early, vital years.

He was a man whose hold on reality became more nearly factual the closer he could live with the possibility of death. It strengthened the necessity and the desirability of breathing, eating and getting out of bed Sundays. Maybe he lacked imagination. but without it. affirmed his physical presence, racing would mean little. There was, too, the naughty possibility that one day a patch of oil perhaps might ... or wet leaves under trees after rain, or the blinding transition from bright sunlight into shadow on a wooded road or a missed gear change well up in the speed range welding the engine solid in an instant. "His death was inadvertent" he would like them to cut on the headstone of the grave . . . except that really that might be a little bitter, a little cynical and that would upset his mother and of course, anyway, he wasn't really bitter at all: just a man chasing his sanity up a fast road.

The road went ahead then down suddenly, like a big dipper on the midway and at the bottom of the dip it narrowed and poured itself gingerly between two outcroppings of rock. Still in the miniature canyon it twisted first to the right and then left, before turning up, like it was painted orj the side wall. At the skyline it leveled immediately and if you weren't ready and had too much power on. why. you took off and daylight showed under the wheels. From there it was straight and level for 2600 yards before quite a bump followed by a dogleg to the left . . . but if you'd ridden it before, you knew what was coming all right. The man knew.

The sun warmed an Iguana and the Iguana watched the road and waited.

The machine straightened from the last bend, came upright from the incredible angle of lean the new tires allowed, the new kidney-shaped tires made of high hysteresis rubber that held the road better than glue. Without a stutter the engine picked up from 6,000 rpm in second gear and sang a clean, ascending note that continued up the scale for an impossible length of time before the white needle of the tachometer touched the white mark on the scale half way between 13.000 and 14.000 rpm. Then the man did several things rather quickly, with his right and left hands and the toe of the right boot. In a fraction of time the ascending scream from the exhausts interrupted and came in again, lower pitched and with something of the quality of an organ and the song was repeated in a different register, again culminating in a climateric of noise that almost snapped the mind and was, no matter how often you heard it. completely overwhelming and exhausting; a sound that was frightening and exhausting the way it is if you stand in a belfry for a brief moment, during a ring of bells. But the man did not hear it like that, like the rocks and the shrubs and the insects that lived by the road; for the man the song of the engine was a loud drone that faded as speed built up and the mounting gale swept noise away and all the rider could hear was the sound of the cyclone he had created, with a drone heard somewhere behind the wind-noise buffeting his helmet. At the highest speeds the rider could no longer judge the speed of the engine by its song, but had to consult the small black dial mounted in front of him.

The white needle, as well as his position on this road which he had come to know, told him it was time and he simultaneously snatched the clutch lever, using the first three fingers of the left hand, eased the throttle with the right hand, stabbed the gear pedal on the right of the machine and opened the throttle again.

The small machine gleamed as improbably under the sun as the equipment of a (Continued on page 75) circus act under arcs. Its tread on the road was light and delicate like the approach of a high wire performer and the roll of drums you got from the band at a circus was the thunder of the torrent of air pouring off the windshield past the rider's head. The machine moved gently up and lown on its suspension as it penetrated the 100 mph barrier and set out again for greater speed still, for the more speed you had the more you wanted and fast was never enough and man and machine had always to go faster, possibly much faster. But the designers were already working on that and next year's machinery would certainly have more speed and then not enough.

Approaching the sudden descent, where it went like the big dipper, the man sat up suddenly from his crouched position behind the fairing, using his body as an additional air brake as he also applied the front, then the rear brakes and blipped the throttle for a downward gear-change that would make engine-braking effect available too. From 117 mph the speed dropped like a hawk stooping until at staid, safe 75 the machine went over the top and the man's heart paused for a second as the front and the back wheel too, lifted from the tarmac and for an instant — like a hawk — the motorcycle was airborne.

As gently as a helicopter the machine lit again and in the same instant the man applied more braking effort. Then, feeling the road adhesion at its maximum, he called for total braking effect as the road slithered ahead of him between the two outcrops of rock.

At full deceleration the machine slammed into the canyon, from the sunlight into deep shade and in that instant the man felt the shock of cold air. With a slipping clutch at 27 mph in first the man tackled the tVist to the right and threw his weight across the road for the sharp left immediately following. For an instant as the machine was perpendicular he snatched gently at the front brake and shut the throttle completely before the machine was heeled at almost 60 degrees to the road and cutting across the apex of the acute, 20 mph turn.

The rider snatched the clutch lever, opened the throttle and applied power to the rear tire by progressive use of the clutch. Still at an acute angle the rear wheel jerked outward in a vicious little skid but did not slide away completely. The man continued the treatment and the tiny slides continued but the speed built up and the angle was less acute and the danger was past.

Straight up the wall then that led out of the tiny canyon, striving for more rpm in 2nd gear now. It was 45, 50, 56 mph, with the engine reaching for peak torque . . , and then no time to select second befor he was off the ground and flying onto the straight and accelerating in third again briefly before taking fourth gear, top; and perching very still on the racing seat then as the needle of the tachometer wound round the dial and stopped moving.

A buzzard, thrown up angrily by the hammer of noise down in the rocks as the man went through, saw from the cockpit

of his eye man and machine indivisible devouring the 2600-yard straight faster than it had ever been travelled before. Faster than the truck drivers did it; faster than the occasional youths in rakish sports cars did it; faster even than the man and woman traveling together in the 5-litre Maserati had done it — and they had seen 138 mph briefly before shutting off with respect for the corner racing toward them. At fractionally over 145 miles per hour the man rolled back the throttle and touched both brake controls, smoothing the speed to a docile 95 for the bend, sweeping from just inside the verge where the thick dust lay across the apex of the curve to just before where the dust commenced again, where he straightened the machine and accelerated, then braked slightly, in order to hit the descending swervers at around 80, or, as he knew it, 10,000 rpm in second.

Thermalling on deft wings the buzzard had watched from the eye of the sun and seen the man go two miles in one minute and 17 seconds, which was fast, except that it should have been faster.

The man did not know he had made a slow time, immediately. He knew only, at first, a tremendous sense of exultation to have controlled that most sophisticated racing motorcycle and to have put it through all its paces and to have survived.

With small motions he quieted the machine and restrained it, throttling the four cylinders and easing the roadspeed to a relaxed 50 mph that felt to him, after his /ide, like fifteen. The man's features relaxed and he looked tired but rather young and no longer part of his machine. Then with a final action of the brakes he brought it to a quick standstill and pushed up the goggles that hid the eyes. He thought of what he had done and he thought of fate and he laughed to himself quietly. The swart man smiled because he had won the game again but his stopwatch told him he had won because he was slow and he smiled without humor because he would have to practice again, properly.

Then the man felt the dull heat suddenly and also looked for a place to empty his bladder and glanced at his wristwatch, for there was a time they would expect him back at the hotel and he returned to life fully over the next three hours, hurt by hurt.

That night he could not sleep well and was awake as first light stole into a corner of the sky, when at last he slept. But in sleep his mind held on to a question he never asked his waking self: was there a fate lurking somewhere in the sun, that came at you fast and straight for about a mile and a half, but made no turning? •